Vehicle safety is determined by a bunch of dummies. Male dummies, to be precise. Yet even though the U.S. population skews female, crash test dummies have been sized to reflect the average male. A female model has been in the works for years, but a bipartisan group of lawmakers wants to speed up the process.

In a recent CBS News report, four senators have introduced the She DRIVES Act, which aims to update multiple facets of NHTSA’s current crash-worthiness testing procedures. Because facts and stats don’t match the populace.

As of the 2020 U.S. Census, females have a slight percentage advantage over males, comprising 50.9% of the population versus 49.1%. Although the percentage is minimal, the translation in actual people equates to a 6,077,659 advantage. However, the risk for severe injury and death for females sees a far greater disparity.

A 2013 NHTSA report lists a 17% increased risk of fatality for female vehicle occupants compared to men. A University of Virginia study in 2019 shows even more dire numbers when it comes to serious injuries in a frontal car crash. University researchers found females have a 73% higher probability of injury, even if wearing their seatbelts. CBS News quoted the senators:

“Whether driving or as passengers, we wanna make sure that women are safe when they get in a vehicle,” said Republican Sen. Deb Fischer of Nebraska.

Democratic Sen. Tammy Duckworth of Illinois added, “So there are all those moms and daughters and sisters and best friends come home.”

Introduced in January, the “She Develops Regulations In Vehicle Equality and Safety Act,” or the “She DRIVES Act” for short, lists Duckworth and Fischer as original sponsors of the Senate bill, as well as Sens. Marsha Blackburn, a Republican from Tennessee, and Patty Murray, a Democrat from Washington. Since then, eight additional co-sponsors have been added to the bill, including male counterparts.

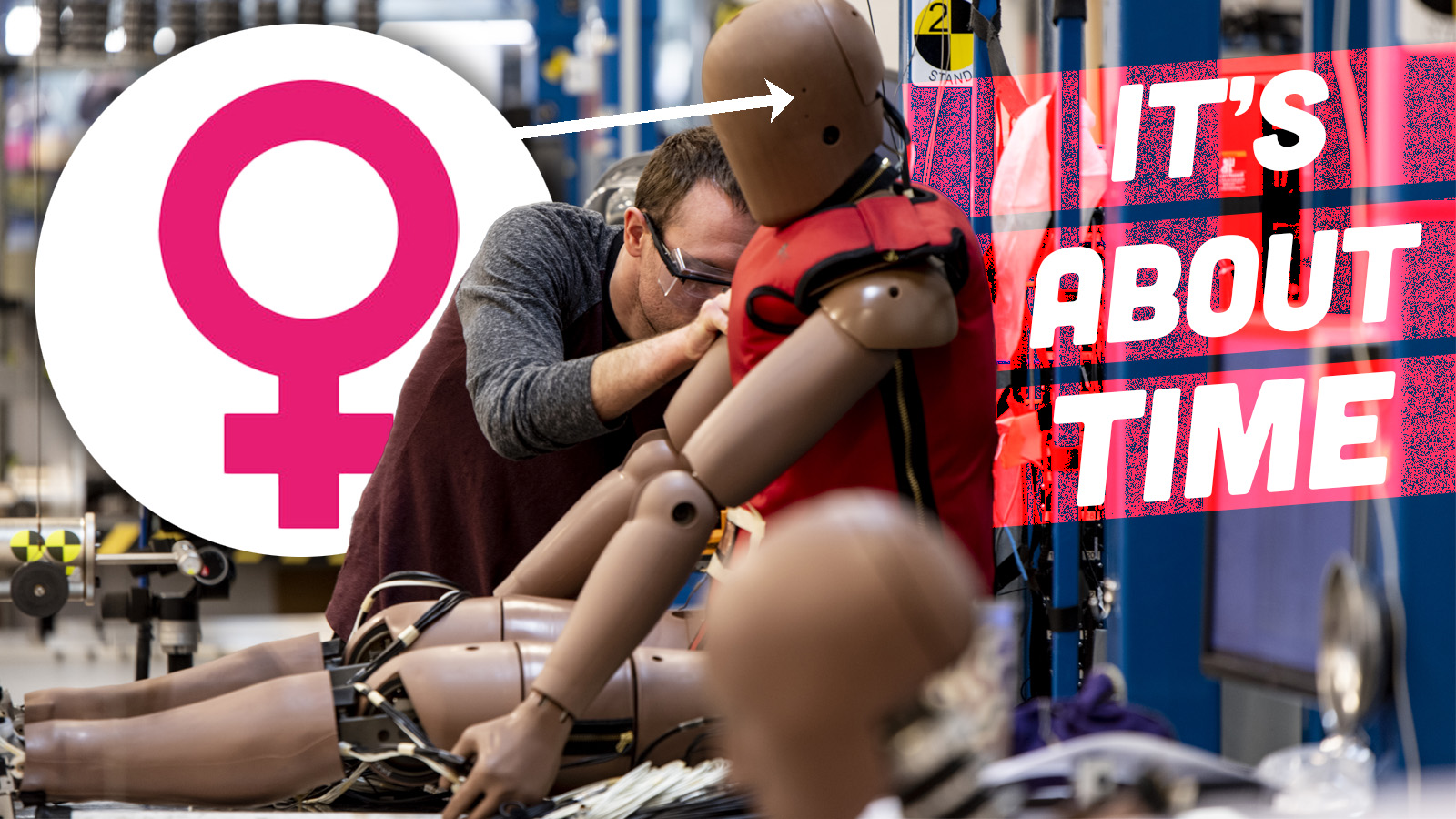

Although the dummy duo, Vince and Larry, are embedded in the brains of certain generations, female crash test dummies do exist, but are definitely on a different and much-delayed timeline. For example, a team of Swedish researchers developed the first one in 2022. Also, Humanetics, the company that builds the dummy testers utilized by NHTSA, offers the THOR-5F, but it is representative of the most petite 5% of women. This means females who are 4’11” and 108 pounds.

The THOR-5F is more diminutive than my mom, whom I tower over with my 5’2″ frame. I’m considered short and, yes, sometimes have trouble reaching the clutch, yet I’m basically oversized compared to this dummy. Still, that’s better than nothing. Humanetics president and CEO Chris Connors told NBC News:

Humanetics’ newer model, called the THOR-5F, has 150 sensors, including in the legs, where female drivers are at a nearly 80% higher risk for injury than male drivers are in the same accident. The model has also been designed to better mimic an actual female body, according to O’Conner.

“This enables us to be able to design cars that are safer for women as well as safer for men,” O’Conner said.

Even with growing support for the She DRIVES Act, implementation won’t be easy or quick. For example, even though a new model has been on the market since 2020, the male crash test dummy currently used by NHTSA was developed in the 1970s. Per the Associated Press:

The crash test dummy currently used in NHTSA five-star testing is called the Hybrid III, which was developed in 1978 and modeled after a 5-foot-9, 171-pound man (the average size in the 1970s but about 29 pounds lighter than today’s average). What’s known as the female dummy is essentially a much smaller version of the male model with a rubber jacket to represent breasts. It’s routinely tested in the passenger seat or the back seat but seldom in the driver’s seat, even though the majority of licensed drivers are women.

As for the She DRIVES Act, the AP acknowledges its bipartisan support, including two former transportation secretaries, but adds a grain of salt:

But for various reasons, the push for new safety requirements has been moving at a sluggish pace. That’s particularly true in the U.S., where much of the research is happening and where around 40,000 people are killed each year in car crashes.

IIHS responded similarly, saying that although a dedicated female crash dummy could be beneficial, resources could be better utilized to find out the why rather than the how when it comes to female crash injuries. Jessica Jermakian, IIHS senior vice president of vehicle research, added perspective via a 2022 statement:

While it’s tempting to believe that putting a female dummy in the driver seat for crash tests will automatically result in safety improvements that benefit women, the reality is more complex.

Improving safety for women requires a more nuanced understanding of the problem — and of the purpose and limits of crash test dummies (more on that in a minute). We also need to consider other tools besides physical dummies that can help address a range of injuries in different types of crashes for all shapes and sizes of people.

The previous year, IIHS released the results of an injury study that analyzed front and side-impact crash reports from 1998 to 2015. Like other data regarding crash injuries, the numbers were stacked against females. However, upon digging deeper, IIHS determined two specific factors as to why: crash type and vehicle size. According to the study:

Though men are involved in more fatal crashes than women, on a per-crash basis, women are 20-28 percent more likely than men to be killed and 37-73 percent more likely to be seriously injured after adjusting for speed and other factors.

However, when IIHS researchers limited the comparison to similar crashes, they found those discrepancies mostly disappeared and that crashworthiness improvements have benefited men and women more or less equally…

In front crashes, they found women were 3 times as likely to experience a moderate injury such as a broken bone or concussion and twice as likely to suffer a serious one like a collapsed lung or traumatic brain injury. In side crashes, the odds of a moderate injury were about equal for men and women, while women were about 50 percent more likely to be seriously injured, but neither of those results was statistically significant.

The IIHS research team further separated the crash data into subsets of “compatible” front crashes to see if the differing anatomies of males and females were the defining factor in injuries, as commonly believed, hence the push for female-specific crash dummies. The analysis offered another possibility:

This subset was restricted to single-vehicle crashes and two-vehicle crashes in which the vehicles were a similar size or weight or the crash configuration was such that a size or weight difference would not have played a big role. To further reduce differences among crashes, only those with a front airbag deployment were included.

The sample included too few cases to do the same thing with side crashes.

Limiting the analysis to compatible front impacts flattened the disparity considerably, though women were still twice as likely to be moderately injured and a bit more likely to be seriously hurt.

Similar to the NHTSA 5-Star Safety Rating, an IIHS Top Safety Pick+ distinction is coveted by automakers. These safety awards are essentially seals of approval, so consumers also take notice. To determine crashworthiness, IIHS conducts a battery of vehicle tests, assigning a grade to each category (poor, marginal, acceptable, and good). To earn a TSP or TSP+ award, vehicles must obtain a specific mix of acceptable and good grades. Such ratings came into play as well, seemingly improving crash safety for females versus males:

A further analysis of those crashes, as well as the unrestricted set of side crashes, showed that good ratings in the Institute’s moderate overlap front and side tests lowered the odds of most injuries more or less equally for both sexes.

In the compatible front crashes, the benefits of a good rating in the moderate overlap front test were greater for women except in the case of leg injuries, where the benefit was similar. In the side-impact crashes, a good rating in the side test benefited men and women about equally where moderate injuries were concerned, but the benefits of a more crashworthy vehicle were greater for women for most types of serious injuries.

These results are in line with previous research that shows serious and fatal injury risk has declined more for women than men as vehicles have gotten safer.

So, if the vehicles colliding are approximately the same size, the injury risk to female occupants does remain higher than that of males, but at a smaller overall probability. Unfortunately, the U.S. is home to the big and bold. For the last 40 years, the nation’s best-selling vehicle was a truck, the Ford F-150, but it was dethroned this year by the Toyota RAV4.

Nevertheless, a compact crossover is larger than a compact car, which women shop for more than men do. A demographic study by automotive research company iSeeCars.com analyzed 54 million car sales and 500,000 inquiries from 2013 to 2015, which falls within the realm of the IIHS crash injury research. Its findings determined that women car buyers leaned toward smaller, more practical vehicles, while men gravitated toward faster sports cars and larger vehicles, such as pickups. Factoring in automobile size, the IIHS 2021 study results concluded:

One explanation of the higher injury rates for women could be vehicle choice. Men and women crashed in minivans and SUVs in about equal proportions. However, around 70 percent of women crashed in cars, compared with about 60 percent of men. More than 20 percent of men crashed in pickups, compared with less than 5 percent of women. Within vehicle classes, men also tended to crash in heavier vehicles, which offer more protection in collisions.

In a separate analysis of data from the federal Fatality Analysis Reporting System, the researchers also found that in two-vehicle front-to-rear and front-to-side crashes, men are more likely to be driving the striking vehicle. Because the driver of the striking vehicle is at lower risk of injury than the struck vehicle in such crashes, this could also account for some of the differences in crash outcomes for men and women.

That being said, even if car sizes and crash points were similar, injury risk is still not equal between men and women. The numbers aren’t even close. The IIHS study showed that females are still 2.5 times more likely to suffer moderate leg injuries and 70% more likely to suffer serious ones. Jermakian doesn’t hide this fact, but did suggest crash mitigation alternatives, which are just as important as crash protection methods.

In these crashes, women and men had similar odds of head and chest injuries — the types most likely to be fatal — but women remained twice as likely to suffer moderate injuries. The higher injury rates for women were primarily in the lower leg and foot.

This study tells us that a big part of the problem comes down to differences in crash types and the interaction of different vehicle types and sizes. Those issues can be addressed, but not through crash testing. Instead, we should implement solutions available today to make striking vehicles less deadly to other road users.

Available safety features, such as automatic emergency braking and intelligent speed assistance (ISA), should be more widely used, Jermakian said, especially on heavy vehicles like trucks. She noted that ISA leads to “fewer vehicles becoming lethal projectiles” and is a requirement for new vehicles sold in Europe, but something the U.S. has yet to act upon.

As for the arguments in favor of a female crash safety dummy, Jermakian recognized that there’d be some benefit to one, but said that it, too, would have similar limitations as the current crop of dummy crashers: they’re just best guesses:

Even as a stand-in for men, the Hybrid III dummy provides at best an approximation of how the body is affected by a crash. It is based on old, limited data from experiments conducted on human subjects and on testing using cadavers and animals. However, the data that we and others in the crash-testing community have accumulated over decades of using it adds substantially to its value. The dummy’s sensors record accelerations, forces and deflections (e.g., how far a rib is pushed inward), and by comparing these measurements from many tests to injuries in many real-world crashes, we have gotten very good at interpreting these numbers.

When it comes to the lower leg and foot injuries that women disproportionately experience, the 50th percentile Hybrid III gives us some information, and it’s unlikely that a smaller, female version would tell us anything different.

Although a gender-based crash tester wouldn’t be a complete waste, Jermakian cautions against the notion that new, enhanced anthropomorphic dummies are the be-all, end-all:

A female dummy in the driver seat would carry a certain positive symbolism for women, but I want more for us than symbolism. To truly achieve equity in crash safety, we need to recommit ourselves to known solutions that we can implement today and to continued research that will point the way forward in the future…

Newer, more sophisticated dummies with additional sensors have been developed and may someday provide deeper insight into the problem. But much more work is needed to first understand how those injuries are occurring and how to interpret data from the newer dummies. Moreover, even a more sophisticated dummy is still just one dummy, standing in for a diverse population.

This isn’t to say hit the brakes on updating crash safety testing and methodology. The federal government made requests for change as far back as 2010. And, in 2023, the U.S. Government Accountability Office called out NHTSA to improve vehicle safety testing, particularly information gathering, because “the dummies may not represent diverse groups of people—like women, older people, or heavier individuals—making it hard to test whether vehicle safety features are effective for everyone.”

NHTSA developed a three-part plan in response. Of course, there’s no real timetable listed or an earmarked budget, but given the typical molasses-like momentum of the feds, we’re actually on a roll here. Especially with bills like the She DRIVES Act gaining positive ground. There’s certainly a need for diversity in how crash safety testing is done, but diversity and standardization of some safety features wouldn’t hurt either.

Meaningless symbolism, because this is the new reality about regulatory priorities:

(hint, NHTSA losing 25% staff)

https://www.roadandtrack.com/news/a65448479/nhtsa-other-us-federal-automotive-safety-agencies-job-losses-trump-doge-buyouts/

“Ya big dummy!”

-Fred Sanford

I thought DEI. was politically incorrect the last 6 months.

I feel like this is the most important part of the entire article: “Instead, we should implement solutions available today to make striking vehicles less deadly to other road users.”

It seems like one of the main ways to make progress is to basically reverse some of the crash testing- instead of a tested vehicle getting hit by a standard sled, have the tested vehicle hit a standard “small car” and only get good ratings if it doesn’t seriously injure the dummy in that other vehicle.

I wonder, do the manufacturers “build to the test” and use these dimensions in their interior designs? I’m only 6′ tall so not far off the average but it would explain a few usability issues I’ve had with various cars over the years.

Edit: As far as the actual topic, if the current testing dummies can’t give accurate/representative data for women for whatever reason then they need to be updated or replaced. Follow the science, and all that.

I suggest the new dummy should be modeled after Lia Thompson.

It’s still early days, but Virtual Testing is one method that the industry is pursuing for improving equity for vehicle occupant safety. The limitations of physical testing by using ATDs (Dummies) of specific sizes, and the high cost of running the tests are often the barriers that restrict expanding to other genders, occupant sizes, and positions.

Virtual testing in a computer simulation with existing ATDs or even Human Body Models removes those resource limitations. But the challenge then becomes how to confirm the results from the Virtual Test are valid? It’s a interesting challenge.

Euro NCAP already uses Virtual Testing in a Side Impact protocol as an option. And even IIHS is introducing a Virtual Testing program in their upcoming Whiplash Protocol to reduce Neck Injury for more occupant types & positions.

https://www.iihs.org/news/detail/virtual-testing-will-help-us-chart-a-new-course-in-neck-injury-prevention

This has nothing to do with your post but that avatar/handle combination is magnificent. Well done.

Yep, the problem is the size and especially the hood height of trucks and SUVs. These selectively kill smaller people (women and children). If for some reason the front of your vehicle needs to be 3 feet or more off the ground, you should need a higher level of licensing, not to be allowed to drive it in school zones, and pay an annual safety fee to fund pedestrian and traffic safety improvements, especially around schools.

I want to be positive about the premise of working to better crash test standards, but I have trouble doing so. When every third truck in my area is lifted to the sky with a bull bar precisely adjusted to be at the elevation of my kid’s heads, what exactly is this crash test data going to do for us?

I don’t disagree with the effort to add a female dummy of average size to the crash test repertoire, but when it comes to reducing deaths and injuries, it seems like the money would be better put towards higher licensing standards and taking the most egregious examples of unsafe vehicles off the road. But knowing that’ll never happen, I guess we’re stuck with accepting the concept of “you’re going to get crushed by this brodozer no matter what, let’s wrap you in a cocoon to limit the length of your hospital stay”.

Yep, I also would like to see lifted vehicles cleared from the roads. Walking one’s kids to school is very illuminating for understanding how much we as a society value children’s lives.

Trucks seem to be designed to protect the ego of their drivers more than the lives of pedestrians.

I don’t dispute that the size of trucks and SUVs is a problem. I wouldn’t have a problem with additional licensing requirements for these vehicles.

My only point of contention is that vehicle size is usually a minor factor in whether a crash occurs. Data shows that pickups and large SUVs are more dangerous when collisions occur, but data also shows most collisions are caused by driver behavior (aggressive driving, driving well over the speed limit, texting, driving drunk, etc.). It would be much higher yield to address those problems.

I am frustrated with how much aggressive and dangerous driving I see on a daily basis. I see a lot of it within full view of the police, yet it doesn’t seem to matter. I’m not sure why crimes like “third offense DUI” even exist (second offense would result in summary execution if I had my way) or why people can get multiple yearly tickets for moving violations without losing their license. Why the hell are dangerous drivers allowed on the roads??? If you can’t drive safely, you should be given a Schwinn or a bus pass – if you stay out of trouble, eventually maybe you can upgrade to an ebike or moped.

It is easy to blame pickup trucks (particularly because they are disproportionately driven by aggressive jackasses), but it would be higher yield to address driver behavior.

It sounds like women are more likely to be injured in accidents. Women are presumably the majority of drivers. What argument is possible against using women as the crash test dummy standard?

Change is scary, hard, and expensive.

I don’t think there are good arguments against using female crash test dummies, especially as the standard other than it will make crash tests more difficult for manufacturers. Probably a long-overdue change. However, there is some concerning language in the quoted releases that will lead to some extremely stupid mandates if taken at face value:

Equity, as in equality of outcomes, is an absurd target for crash safety that willfully defies basic scientific principles. It is a basic fact of biology that homo sapiens is a sexually dimorphic species, and the male is on average: taller, heavier, and possesses greater muscle mass and bone density. It is a basic fact of biology that greater muscle mass and higher bone density allows an individual to absorb greater amounts of energy without suffering injury. In an event with some fixed amount of energy to be distributed (ie a car crash) it necessarily follows that on average male occupants will suffer less injuries and when injured they will be less severely harmed, as on average they can absorb higher amounts of energy in comparison to female occupants. This remains true at all energy levels and collision types. So, the only way to break this inequity appears to be to deliberately design cars to be less safe for certain segments of the population, most likely those taller and heavier.

Why would using female dummies “make crash tests more difficult for manufacturers”? It would skew the results differently, but that’s not the same as being more difficult. They just order the new (female) model of dummy from Dummies-R-Us and carry on as before.

The argument that males can better survive injury is probably true, and may mean that females will always suffer worse injuries. But that doesn’t mean using female dummies would make cars “less safe” for males.

Using female dummies makes the test more difficult for the same reason child crash test dummies make the test more difficult: there is a set amount of energy to be dissipated, which will result in a set amount of force imparted to the occupants, and with the smaller mass of female/child dummies the acceleration due to impact increases, which means your injury ratings (which are determined as a function of acceleration) increase. So any given impact criterion requires greater occupant protection than with male dummies.

I didn’t say that it did, but if, as a certain senior VP at the IIHS quoted in the article says, the goal is “crash equity” then the only way to achieve that is to actively make cars less safe for males. Now I’m hoping this was the usual corpo-DEI BS with words not actually meaning what the dictionary says they do, but taken at face value it does have alarming implications.

So you’re saying that it’s not that the tests using female dummies would be more difficult, but that they’d yield results the tester doesn’t want to see. That’s probably true. I do get that you think “equity” is bad, but probably changes are not possible that will result in identical risk for both M & F.

Why not have tests where the standard protection level is for the more vulnerable (and probably more numerous) group? In the US (and likely most countries) there are more females than males, thus probably more females riding in cars. (Maybe not females in car accidents, depending on how badly the stupid actions of young males skews the numbers.) If the same injury criteria were not changed, using female dummies would almost certainly require increased protection for both men and women.

I don’t specialize in biomechanical risk factors, but I know people who do and have worked in the area, and it is my understanding that identical risk is essentially impossible to achieve in any emergency escape or crash protection system.

I hope this is what they actually mean they are doing, and would make sense. But your succinct description would be way to simple for a corpo PR release, so they had to add in a sizeable amount of BS. The next step would be to mimic aerospace standards and do your statistical sampling on a 50-50 mix of male and female occupants with outlier studies for 95th percentile males (ie > 6’2″ and 250 lbs) and 5th percentile females (under 4’11”, 100 lbs) with some children thrown in the mix as well.

I’m trying to say this with as little political controversy as possible. I’m pretty confident that these statements are factual.

The current administration’s policies have clearly “de-prioritized” women’s health, de-prioritized consumer rights and safety, de-prioritized government oversight and inspections, and eliminated a significant amount of government funding for factual/scientific data collection which used to be used to inform public policy. It has focused on policies which eliminate government regulations, which lower cost for businesses, and which increase profit opportunities for any commercial entity.

I will be truly quite surprised if/when a bill passes which intends to increase the amount of testing and which may put additional safety design burdens on businesses, all for the sake of a female gender based health improvement. This bill feels like an anachronism.

Update both man and woman dummies to fat people. Sadly a lot of average height women in US are 170+ lbs so the old 70s one is ok for them. It’s not some far off, edge of the bell curve test. More people die every year from heart disease from being obese. Like 500k + Lets all have a salad and take a walk!

If I understand the procedure right, you first need obese people who donate their remains to science so you can test for the relevant data, which is a rather complicated (and rightly so, for ethical reasons) and expensive process. A dummy only gives you numbers, but to interpret them you need data from actual bodies.

IDK how detailed these crash test dummies are, but there is more to a human body than weight, especially when the point of the change is to account for differences in sex.

The engineer in me (i swear, he’s there) says: Even if you don’t think it’s the end-all, be-all solution, at least go collect the data to find out and inform yourself as to what it might be.

The old “don’t let perfection get in the way of progress” adage applies here.

“In side crashes, the odds of a moderate injury were about equal for men and women, while women were about 50 percent more likely to be seriously injured, but neither of those results was statistically significant.”

What? Unless I’m reading this wrong, that would only make sense if the odds of being injured in a crash were statistically insignificant to begin with.

I’m not sure I follow. The odds of something is the odds of that event to happen as measured by collecting some data. It has no sense to talk of statistically significative or not.

You introduce the concept of statistically significative only when you are testing an hypothesis (odds of event A is the same to the odds of event B) etc. It is possible for the odds of them to be the same but not statistically significative if there is a small difference, but given the number of samples, we cannot say they are different.

And here the article is saying odds of A (male+moderate) = odds of B (female + moderate) while odds of C (male+serious) < odds of D (female +serious). Since the four class are disjoint, I’m not sure you can infer anything on the odds of male injuries or female injuries except male injuries< female injuries (but you can’t state if the difference is statistically significant or not)

I was married to a woman about 5’0″. There wasn’t any way for her to operate a car while remaining the suggested 1′ distance from the airbag. We just picked pre-airbag cars for her. Dunno what she does now.

My mum always drove the smallest hatchbacks available, but she needed a cushion between herself and the backrest to be able to reach the pedals. With the driver’s door open, she looked like the aftermath of a nasty front-end collision.

When I was growing up, one of my friend’s had a similar issue with his mum as she was 40% as tall as a Nissan Pao is long, or 0.4pao.

From memory she had blocks on the pedals or similar so that she could reach them with her legs and cushions to get higher.

Perhaps a vehicle with adjustable pedals? (All of which seem to be full-size SUVs.)

In addition to testing what happens after a crash, I wish crash avoidance was also taken into account. I can describe 3 separate times where if I were driving my Yukon I’d have definitely been involved if not rolled over, but instead was able to avoid it and watch all the cars behind me crash because I was driving my toy car with fancy tires, brakes, and suspension.

To minimize injuries let’s stop phone usage in cars. Then we can increase visibility to drivers. Ooh let’s add in better enforcement of traffic laws (not just speeding). Stricter driver licence requirements?