From Avanti to Zimmer, every orphaned car brand has its armchair CEOs who argue that, if only they had been in charge, the company would still be making cars today. But most of these analyses are unrealistic and clouded by a love of the brand.

One of the biggest challenges in producing and writing our documentary, The Last Independent Automaker, was looking past our own internal biases toward American Motors to tell an accurate, balanced story. Because AMC was the perennial underdog in the U.S. automotive market, it was tempting to blame its demise as an independent company on outside factors: the economy, government regulation, the Big Three, the Japanese, the first oil crisis, the second oil crisis, Lee Iacocca, etc.

These were very real challenges, but placing too much blame on these external factors can hide the fact that, yes, even AMC made mistakes. And sometimes, they were big ones.

This article coincides nicely with Episode 4 of The Last Independent Automaker, which focuses on the development and production of the AMC Pacer–a vehicle that even the most strident AMC enthusiast will admit caused a lot of problems for the company.

Here, I’ll examine what I think were some of AMC’s biggest mistakes and how some of them could have been avoided. This isn’t an exhaustive list, and some of it is subjective, but I think the conclusions are worth sharing.

Stages of Decline

Around 2016 I read the insightful book, How the Mighty Fall: and Why Some Companies Never Give In, by Jim Collins. Although not specifically about cars, it provides a data-backed framework of why and how successful companies fail. Collins and his research team broke down corporate failure into five stages of decline:

- Hubris born of success: Corporate arrogance creeps in during profitable years, and management starts to assume that because they were right in the past, they’ll always be right in the future. Success is seen as a given and not the result of hard work and discipline.

- Undisciplined pursuit of more: The successful company begins to expand faster than it can afford: hiring too many people, ramping up production too quickly, jumping into untested markets, spending too much on overhead, building fancy new offices, etc. Costs spiral upward, leaving the business dangerously exposed in the case of a downturn.

- Denial of risk and peril: When the hard data starts to suggest there is a problem, management finds ways to “explain it away” and blame it on external factors. For example: “The economy is just bad this quarter,” “gas prices will eventually come back down,” “Japanese cars are just a fad.” The lack of introspection prevents real problems from being addressed until it’s too late.

- Grasping for salvation: When reality finally catches up and throws the business into legitimate, undeniable decline, the knee-jerk reaction of bad management is to find a silver bullet that will fix everything overnight, like a new CEO, a hot new product, a new corporate strategy, or a new merger. Such changes are exciting, but rarely include the boring, incremental, necessary discipline required for sustained success. Decline doesn’t happen overnight and neither does recovery, but gambling the entire company’s future on a single person, plan, or product can be deadly.

- Capitulation to irrelevance or death: Having wasted precious time and money lurching back and forth after silver bullet solutions, the company hits the financial reality that it can no longer operate independently. Management makes the conscious choice to give up, and the company either has to be sold, go bankrupt, or go out of business.

Interestingly, Collins said that the stages are not a one-way street. Companies can spend years or even decades flipping between stages one through four as they ebb and flow. It is only at Stage 5 that a business reaches the point of no return.

These insights from How the Mighty Fall felt like a pair of X-ray goggles; suddenly, these same stages of decline were visible at American Motors. From its founding in 1954 to its purchase by Chrysler in 1987, AMC’s history was full of peaks and valleys, triumphs and tragedies. It was only when the company had to sell itself to stay alive that it truly died.

Mistake 1: The NOW Cars

If you’ve watched Episode 1 of our documentary, you know that George Romney pulled off a magnificent turnaround at AMC in the late 1950s by filling a market niche the Big Three had missed: economical, efficient, compact cars. AMC’s various Rambler models were smaller than their American competition but bigger than foreign European imports. They were not super glamorous, but they were profitable.

Romney did make some missteps during his tenure, but perhaps his (and AMC’s board’s) biggest was choosing the wrong successors when he left the company in 1962 to become governor of Michigan. In his place, Richard Cross became chairman, and Roy Abernethy became President and CEO.

As the former VP of sales, Abernethy had been with Romney on the “front lines” of the compact car crusade, helping AMC dealers turn Ramblers into best-sellers. By all accounts, Abernethy was instrumental in AMC’s turnaround, but as we explain in Episode 2, once he was in the driver’s seat he made a big U-turn.

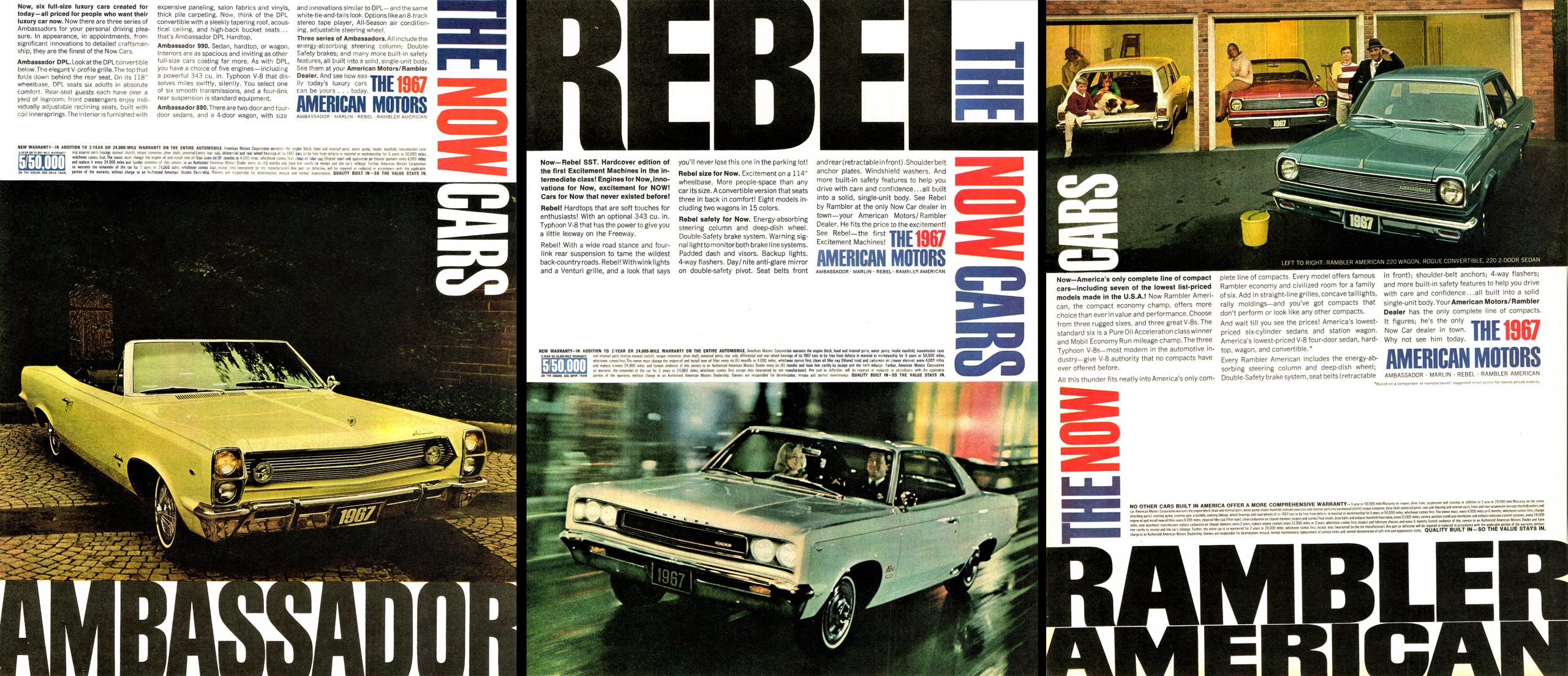

Romney had left just the company as the Big Three were invading AMC’s compact car niche with the Plymouth Valiant, Ford Falcon, Chevy Corvair, and Chevy II. Rather than double down in the Rambler’s core market, Abernethy instead tried to move the company upmarket with larger, fancier cars. The new models were beautiful (the ‘65-’66 Ambassador is a favorite of mine), but the tooling costs for the new bodies and frequent styling changes were huge.

Abernethy also botched AMC’s entrance into the performance car wars by insisting the new Marlin be large enough to seat 6, instead of copying the compact Mustang’s 2+2 design. Simultaneously, AMC’s smaller Ramblers were rapidly losing market share to Volkswagen and other foreign imports.

As a result, AMC missed the emerging pony car market, squandered its lead in the compact car market, and failed to establish a serious foothold in the luxury market. With rising costs and falling sales, Abernethy forged ahead with even larger redesigns for 1967, which some AMC managers quietly called “Roy’s cars” to distance themselves from them.

Again, sales were disappointing, and 1966 became AMC’s first year in the red since 1958. As a result, AMC’s board forced Roy Abernethy into “early retirement” in 1967. (To his credit, he did approve production of the 1968 Javelin and AMX before he left.)

Looking at the stages of decline, AMC came dangerously close to Stage 4 during the 1960s.

Stage 1: Management’s hubris was high after the magnificent 1950s turnaround …

Stage 2: Which fueled Abernethy’s undisciplined gamble to abandon AMC’s successful core business to pursue something unproven …

Stage 3: And when the new models floundered, management responded not by reversing course, but by pouring more money into even bigger cars.

I do not think Roy Abernethy was dumb or unqualified, and he faced a very challenging market during a time of great industry transition. I think he made some foolish mistakes, however. There are many AMC enthusiasts (especially Rambler enthusiasts) who think George Romney should have stayed at the company forever. Such wistfulness is understandable, but not realistic. Men who run for president of the United States would not be satisfied staying on as president of Detroit’s smallest automaker. Plus, there is no guarantee AMC would have continued to prosper had he stayed. It’s probable that Romney would have missed the pony car market also, not by building larger cars instead, but by resisting increased performance and horsepower.

My Suggestion: At the critical turning point in 1962, I think American Motors should have doubled down in the economy market and worked hard to increase its volumes and reduce overhead costs. Simultaneously, it should have carefully waded into the pony car market with a vehicle like the compact Rambler Tarpon, the concept car that inspired the larger Marlin. While the rest of the Big Three would have spent their resources on muscle cars, American Motors could have entrenched itself as a leader in the compact segment and perhaps been better prepared for the rise of Volkswagen and Japanese imports during the 60s and 70s. It wouldn’t have been glamorous, but it could have worked.

Mistake 2: The Pacer (and Matador and Wankel and…)

By the early 70s, AMC offered a full lineup that essentially matched the Big Three model-for-model, which–as past experience showed–was a costly and risky move. But as we explained in Episode 3, one difference from Abernethy’s strategy was that these models shared more parts and body panels between them, keeping tooling costs down despite AMC’s lower volumes.

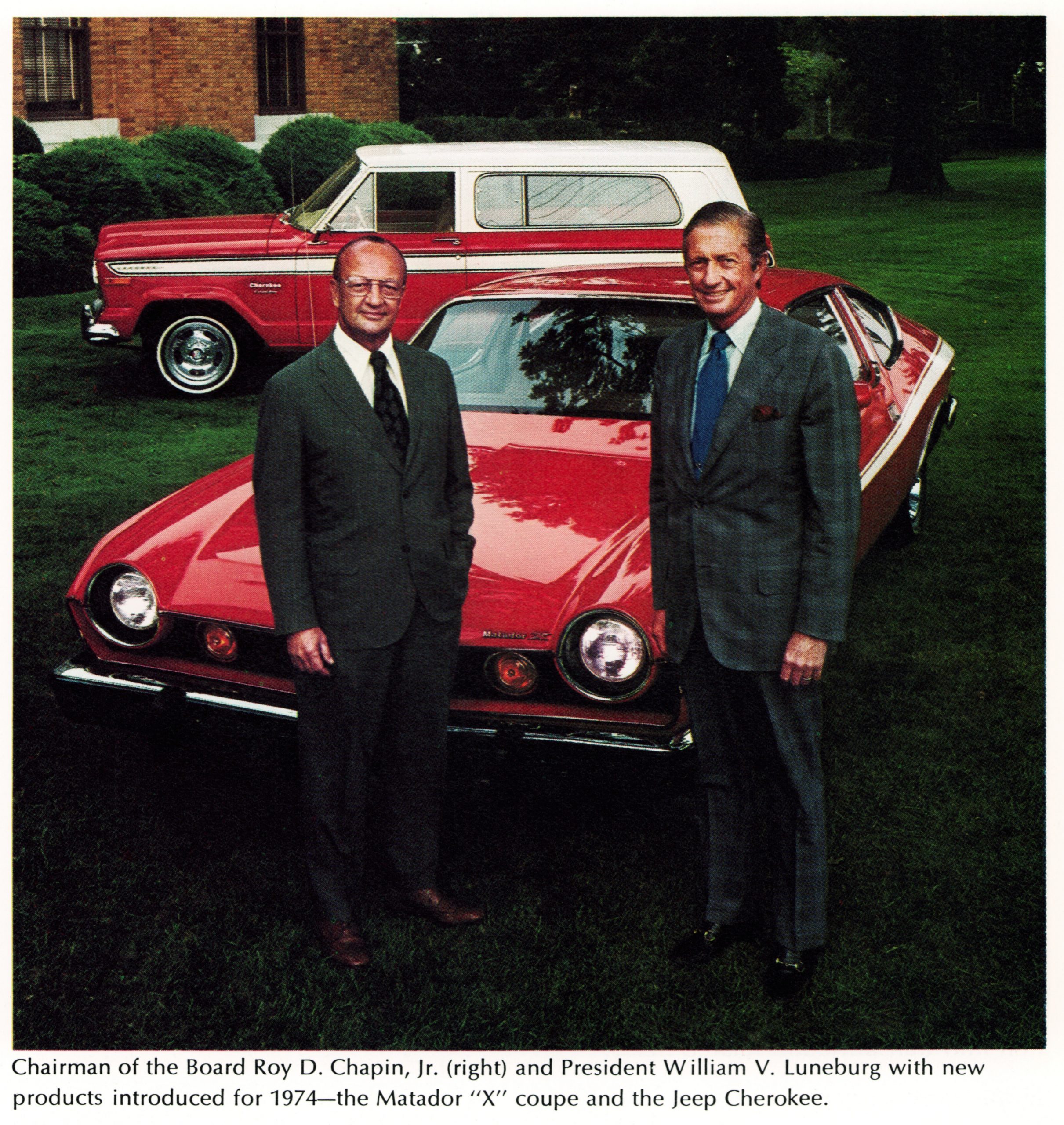

But after a few years of this strategy, AMC abandoned it again with two bold mistakes: the Matador Coupe and the Pacer.

The 1974 Matador Coupe was the company’s attempt to cash in on the booming personal luxury car segment with an ostentatiously styled two-door. The old ‘73 Matador Coupe had shared a lot with the Matador sedan and wagon, but the redesigned ‘74 model had an all-new, completely unique bodyshell that couldn’t be adapted into a 4-door. While sales of the coupe did increase significantly, they did not offset the tooling costs for a completely new car–especially one limited to just one bodystyle. Having been launched into a crowded market with unconventional styling, Matador Coupe sales soon faltered while customers bought Chevy Monte Carlos and Oldsmobile Cutlasses in droves. (Which is a shame, because the Matador is a cool-looking car.)

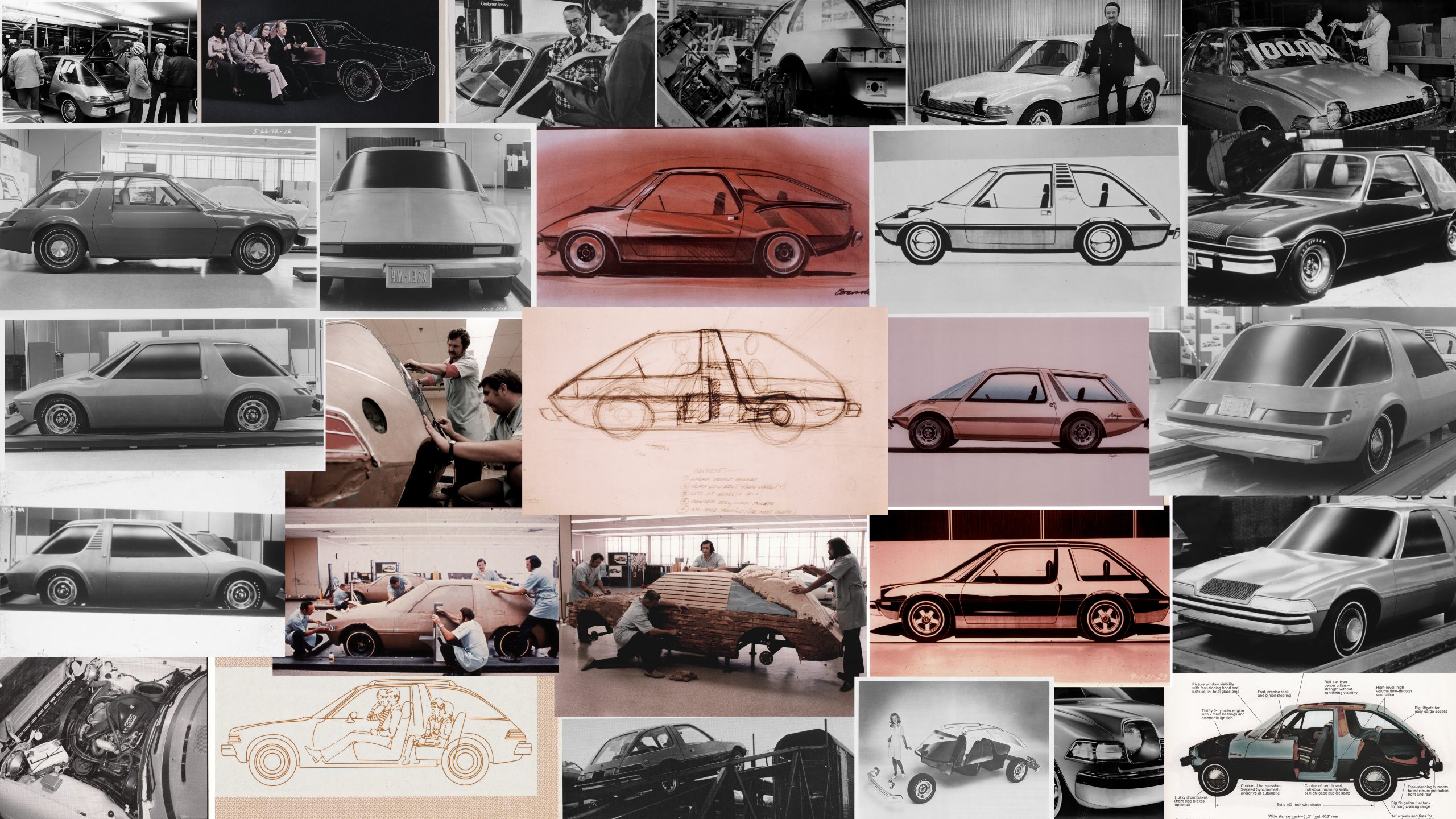

This mistake was repeated with the 1975 Pacer, which was another car that shared no body tooling with existing models. I’ve covered the Pacer story in two separate documentaries, so I’ll give the abbreviated version here:

Intended to be a futuristic commuter vehicle with the noble goal of maximizing occupant space while minimizing exterior size, the Pacer was supposed to be powered by a new Wankel rotary engine that AMC would buy from General Motors, until GM delayed and eventually cancelled the program after problems with fuel consumption and emissions. This forced AMC into a costly redesign, shoehorning its heavier cast-iron inline six into the Pacer. This required heavier brakes and suspension, which had a cascading effect on weight, which was made even worse by the car’s huge, heavy windows. (Glass being heavier than steel.)

Unlike the Matador, the Pacer had no direct competitors. “The First Wide Small Car” was billed as an alternative to cheap subcompacts and compacts and was a big hit at first. Unfortunately, the excitement didn’t last, as the car’s room and comfort were quickly overshadowed by its poor gas mileage (a result of the excess weight) and unusual styling. Sales began to slide and never recovered. AMC had plans to expand into more Pacer variants to help spread tooling costs, but the only one that came to fruition was the Pacer station wagon in 1977, and that wasn’t enough to reverse its fortunes.

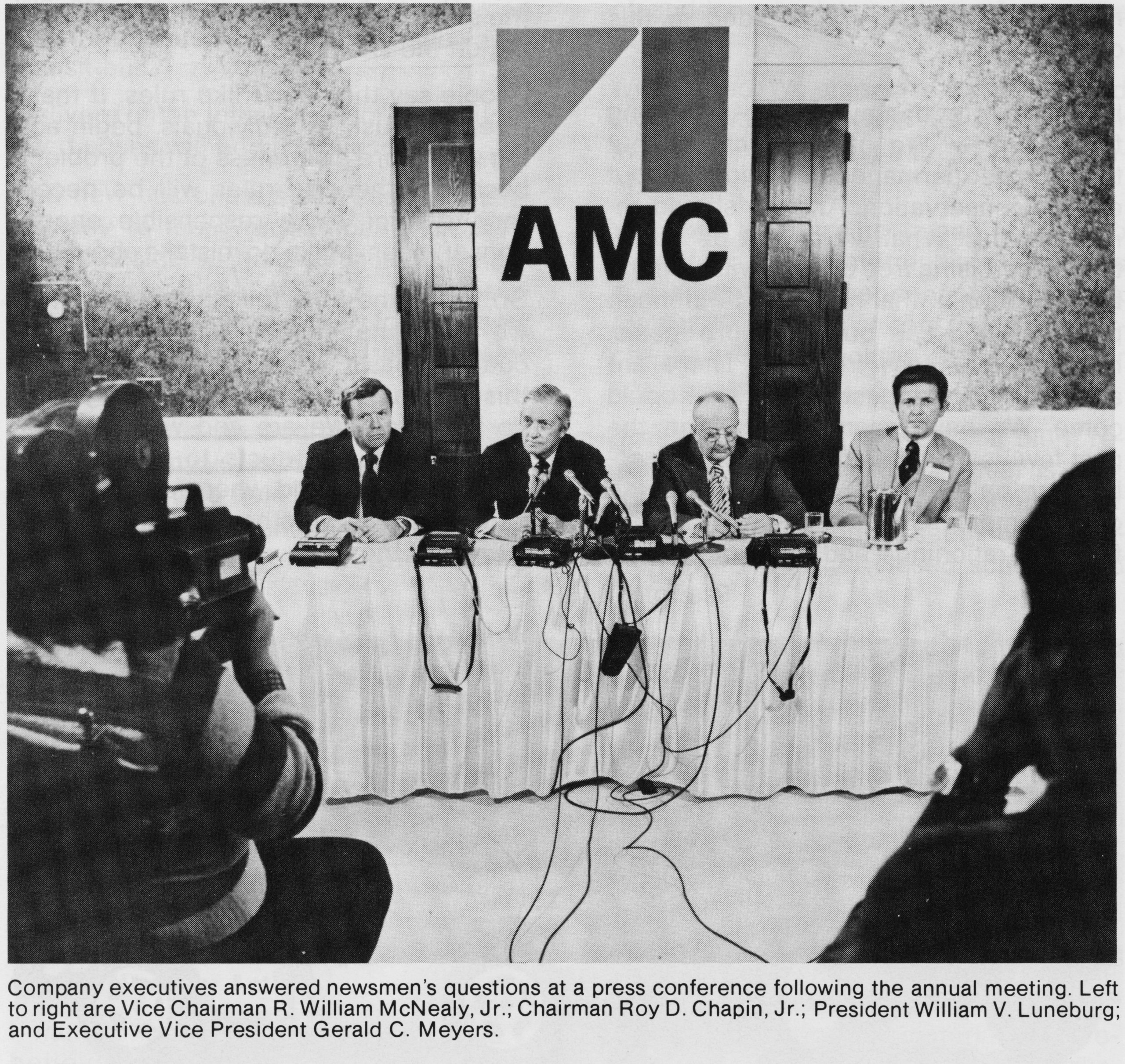

When you zoom out, the Matador and Pacer were part of a larger spending problem at AMC during this era under president Bill Luneburg and Chairman/CEO Roy Chapin Jr. Their successful rebranding of AMC with the Javelin and AMX in the late 60s, combined with the success of the Gremlin and Hornet during the 1973-74 oil crisis, had fueled a false sense of security that American Motors could do no wrong.

Not all of their splurges were foolish; buying Jeep in 1969 was probably the greatest decision AMC ever made. But other choices, like expanding production capacity, hiring scores of new employees, and investing in costly new car designs, all caused significant increases in overhead. As overhead rose, so did the number of cars AMC had to sell to stay profitable, leaving it more exposed to danger.

The money spent on Pacer, Matador, and other projects kept American Motors from reinvesting in its bread-and-butter Hornet and Gremlin lines, meaning when sales collapsed in 1977, the company was caught with an aging lineup and no capital to redesign it–driving it into the arms of the French automaker, Renault.

Applying our framework, we see:

Stage 1: False confidence caused by the success of the Javelin, AMX, Hornet, Gremlin, and generally good years in the early 70s.

Stage 2: Expanding production, splurging on new acquisitions, and pouring money into designs that didn’t share tooling with other models, and gambling on unproven Wankel technology.

Stage 3: Ignoring that Hornet and Gremlin were getting stale (both had gone 6+ years without a major refresh) and overlooking the Pacer’s weight and gas mileage problems while in development.

The Matador and the Pacer were bold, creative, and even enjoyable cars. But they did not return the profits AMC expected, and their effect on the company was detrimental.

My Suggestion: I think the most heartbreaking part of the Pacer story is that AMC almost took a different path. In 1971, when product planners first greenlit the Pacer program, one of the runner-up proposals was a compact luxury car, which eventually became the 1978 AMC Concord. Built on a shoestring budget, the Concord was little more than a warmed-over Hornet with velour seats and added sound insulation–yet it was a moderate success.

However, if management had chosen the Concord over the Pacer in 1971, not only could AMC have invested more money in the design, but the car would have debuted three years earlier. As a result, it would have beaten the Cadillac Seville to market and gone toe-to-toe with the new Ford Granada. Both the Seville and Granada proved America wanted downsized luxury cars, and AMC could have ridden that wave, instead of jumping in after it. Concord would have shared tooling with Hornet and Gremlin, leaving AMC more money for important jobs like developing a new 4-cylinder engine, revamping Jeep products, and refreshing its other models.

In addition, management should have avoided building the Matador coupe and instead combined the Matador / Ambassador into one line for 1974. AMC was never going to be a major player in the mid-size/full-size car space. The Concord could be a mini personal luxury car and attract those buyers, while the combined Matabassaor line could just exist as a participation model for folks who were determined to own a large AMC. More importantly, I would have never approved the disastrous ‘74 Matador coffin-nose grill and instead kept the much handsomer ‘74 Ambassador front end, which bizarrely only lasted one year.

Mistake 3: The French Disconnect

When Gerald Meyers became CEO of AMC in 1977, he was handed a company in trouble. He saw the best way out of that trouble as building an all-new front-wheel-drive subcompact like the rest of the industry, despite the segment having grown hyper-competitive with very thin margins. AMC had squandered its lead in the small car market during the 1960s, and it had squandered the capital needed to regain it in the 1970s. Now, its only hope of building a new small car was through an outside partner. But while GM, Ford, and Chrysler had European operations with small car experience, plus ownership stakes in Japanese rivals like Isuzu, Mazda, and Mitsubishi, American Motors had neither of those advantages.

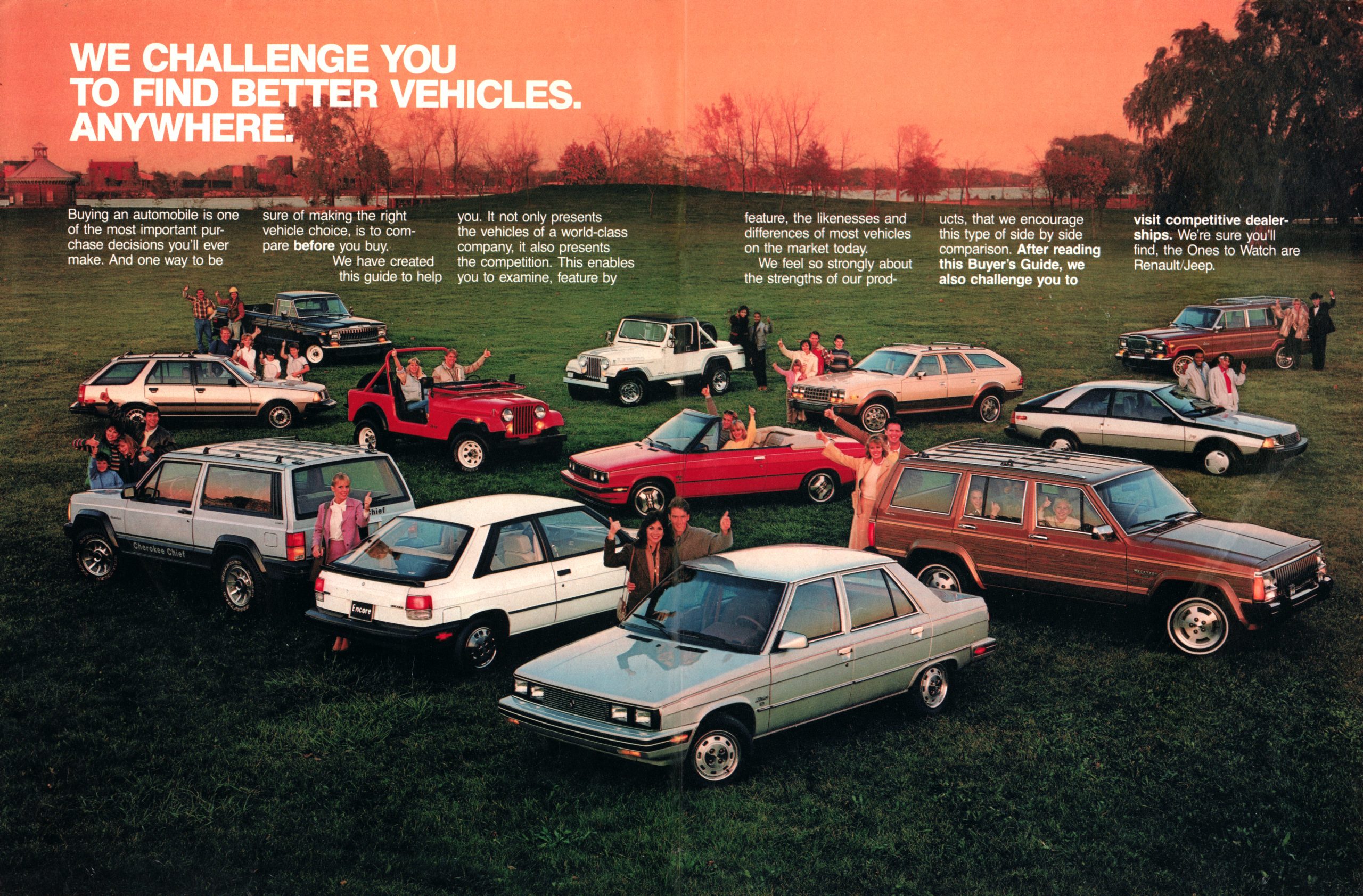

At some point in the mid-70s, AMC began shopping for a foreign partner, meeting with Peugeot and even Honda. After Gerry Meyers took over, he ultimately signed a distribution and manufacturing deal with Renault in 1978. As a world leader in front-wheel-drive cars with a desire to grow in the U.S., it seemed like a perfect match. But if you’ve read my previous story on the topic, you know their marriage was… troubled.

What’s interesting is, the AMC-Renault matchup originally was meant to be just a partnership, not a financial merger. It wasn’t until the 1979 oil crisis caused Jeep sales to collapse that Renault bailed out AMC by buying 46.1% of the company.

From there, the French slowly took over and forced Meyers out. As we explain in Episode 5 and Episode 6 of our documentary, things in the early 80s got pretty dire, with Renault spending $200,000,000 to bring the new American-made 1983 Renault Alliance subcompact and the new 1984 Jeep XJ models to market. With sales down across the board, Renault and AMC pinned all their hopes on these two products.

Both were initially hits, but only the XJ had real staying power. Whether imported from France or built at AMC’s Kenosha plants, Renault learned too late that their cars were all just a little “too French” and a little too unreliable for American drivers. When gas prices receded in the mid-80s and buyers flocked back to full-size cars, AMC and Renault found themselves stuck with a lineup of only small cars, in a shrinking and intensely competitive market. No amount of Jeep profits could offset the losses from the car division, leaving AMC and Renault to pin their hopes once again on another new product, the upcoming Renault Premier mid-size sedan. But before the Premier could arrive, political unrest in France forced the automaker to sell its share of AMC to Chrysler in 1987, and Lee Iacocca was all too happy to acquire AMC and its legendary Jeep line for a cool $2 billion. AMC was gone.

Looking at our framework, Meyers took the reins when AMC was deep into Stage 3: denial and cresting Stage 4: grasping for salvation. In How the Mighty Fall, Jim Collins warns that companies in desperate situations can often react like a drowning person thrashing around in the water, i.e., their erratic behavior can unintentionally make the situation worse, not better. That’s not to say that companies in desperate times shouldn’t take bold moves. Rather, it’s that a desperate company should take calm, disciplined steps to avoid disaster.

Instead, AMC began grasping:

Grasp 1: Seeing a new subcompact as the best way back to prosperity (despite the market segment having notoriously thin margins) and seeing a foreign partnership as the only means to it.

Grasp 2: Partnering with a French automaker that had little experience in the U.S. and a poor understanding of the U.S. market.

Grasp 3: Pinning the company’s hopes on just two models, one of which (the Alliance) was arriving late to the hottest, most competitive segment of the market.

Grasp 4: When the Alliance (and its hatchback variant, Encore) didn’t pan out, the companies then pinned their hopes to the mid-size Renault Premier, which–like the Alliance before it–would arrive late to what was then the hottest segment of the market.

Interestingly, one of those grasps, the XJ, turned out to be a big hit! But its success was overshadowed by the collapse of Alliance sales in 1985. This only furthers the point that one silver bullet is rarely enough to save a company. It takes several hits in a row.

My Suggestions: Like Roy Abernethy, I don’t think Gerald Meyers was dumb or unqualified. Having actually met the man, I was impressed by his wisdom and candor. He was handed a tough situation and – had it worked – his plan for the Renault partnership would have actually made a lot of sense. And without Renault, we would have never gotten the Jeep XJ!

Given how things all turned out, I wish AMC had partnered with Honda in the late 70s instead. Unlike the French, the Japanese worked hard to understand the American consumers and adapt their products for that market. If AMC and Honda had entered a manufacturing agreement, AMC’s Kenosha plant would have been working overtime to build Accords and Civics, and possibly rebadged AMCs. Pairing Honda’s lineup with Jeep’s offerings, dealers would have had a field day.

Sadly, I can’t really figure out how serious the negotiations ever got. Information is incredibly scarce, and any of the executives who would have been involved with those discussions have passed away. So while the daydream may be exciting, it’s possible that things never progressed past a few meetings.

But there was an alternative choice to Meyer’s plan that was a lot more realistic, and it didn’t involve building small cars … or any cars, actually.

I recently wrote an alternate history imagining if marketing executive Bill McNealy had gotten the top job at AMC instead of Meyers. In 1977, McNealy wrote a remarkably clear-eyed proposal where he insisted AMC should leave the passenger car business entirely and focus all of its resources on building Jeeps. He argued that the compact and subcompact segments had become so dominated by the import brands that AMC didn’t have the technology, capital, or volume to make any money in those markets. Instead, he suggested selling the passenger car operations as a tax write-off and pouring resources into a new fuel-efficient Jeep for 1981.

With a downsized fuel-efficient Jeep arriving in the midst of the 1979-80 oil crisis, AMC would have one of the only compact SUVs on the market. Having sold its passenger car business, the massive overhead and losses from that division would have been gone. To keep dealers happy, McNealy advocated that AMC sign distribution deals with a handful of import brands, which would be much less capital-intensive than a manufacturing agreement. It was a bold plan, based on empirical evidence, and would have required extreme discipline to execute. But it could have worked! Sadly, AMC’s board was too scared to abandon the passenger car business, and they ultimately chose Meyers to lead the company.

Of course, McNealy’s plan was not without flaws. Without Renault’s capital and technology, would the Jeep XJ have been such a world-beater? And while an independent Jeep would have dominated the SUV market in the 1980s, would it have been crushed when the Big Three threw their full weight into the game in the 1990s? Or, Jeep being the invaluable brand that it was, would a larger automaker have scooped it up anyway? It’s impossible to know.

They Say Hindsight’s 20/20…

As I said at the beginning, our team had to walk a fine line when making The Last Independent Automaker. It’s lazy and inaccurate to paint American Motors as a victim of circumstance, with no control over its fate. The company made real mistakes. On the other hand, I don’t want to judge AMC management too harshly. As historian David McCullough points out, people in history didn’t know they were living in historic times. Unlike us, they didn’t have the advantage of knowing how everything turned out. Had I been in Roy Abernethy’s or Roy Chapin’s or Gerry Meyers’ positions with the information they had at the time, I don’t know if I would have done any better.

One reason why automotive history appeals to me so much is that I think it has valuable lessons for the present. If I told you I just made a documentary about the automotive industry undergoing rapid changes from new technology, globalization, automation, environmental regulation, economic recessions, and a spike in interest rates, you’d think I was talking about today, not 50 years ago! The lessons from American Motors, what it did right and what it did wrong, are still relevant.

And that’s why I’m so proud that my friends and I got to tell this story.

The Last Independent Automaker is available to watch now on YouTube, the PBS app, and on Public Television stations around the country.

The series is distributed by American Public Television. Maryland Public Television is the presenting station. The Automotive Hall of Fame provided fiduciary assistance. The Last Independent Automaker is funded in part by Visit Detroit, The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and MotorCities National Heritage Area. It is also funded by over 375 individuals and organizations who contributed through the project’s Crowdfunding campaign.

Top graphic images: AMC / The Last Independent Automaker

Just watched your documentary on PBS streaming this past weekend – It was quite well done!

Make me wish Dad had brought home a Rambler rather than the Opel Kadett Sport Coupe in 1967…

So sad to see how Chrysler abused AMC workers at the end – so it seems karmic how Daimler Benz treated Chrysler afterwards.

I quite enjoyed the documentary! I watched each episode shortly after it came into YouTube!

Your photo of Kosco AMC Jeep brought back some bad memories for me. Back when I was much younger, I put a deposit down on a used 1980 Trans Am, the unrestrained desire of my adolescence. The dealer, located on Route 17 in Paramus, NJ, sold the car out from under me, even with a $1,000 deposit. I recall it took my father and I causing a scene inside of the dealership before we got our money back. Many years later, the Kosco’s owned a Harley Dealership on Route 23 in Kinnelon NJ. It is now a furniture store…that should tell you something about their business acumen. On another note, many happy memories were made riding in the rear hatch area of my dad’s 1974 Gremlin, 3 speed manual, so I didn’t have to sit next to my sister.

Well done Joe. I just binge watched the entire series last night. I rather enjoyed it. Thank you for the work you put in on this series.

Life and history are filled with so many “what ifs”. If the Wankel had lived up to its earlier promises then Pacer could have been a brilliant move. If AMC had a decent four-cylinder then the Pacer would not have been so heavy and mileage would have been better. I think the Pacer was a bold move and it did sell well initially but they definitely kept it on too long.

I will agree the Matador Coupe was a mistake. It was ugly from day one and had horrible resale values which made sales drop very quickly with the years.

When you get to the fork in the road, take it!