From Avanti to Zimmer, every orphaned car brand has its armchair CEOs who argue that, if only they had been in charge, the company would still be making cars today. But most of these analyses are unrealistic and clouded by a love of the brand.

One of the biggest challenges in producing and writing our documentary, The Last Independent Automaker, was looking past our own internal biases toward American Motors to tell an accurate, balanced story. Because AMC was the perennial underdog in the U.S. automotive market, it was tempting to blame its demise as an independent company on outside factors: the economy, government regulation, the Big Three, the Japanese, the first oil crisis, the second oil crisis, Lee Iacocca, etc.

These were very real challenges, but placing too much blame on these external factors can hide the fact that, yes, even AMC made mistakes. And sometimes, they were big ones.

This article coincides nicely with Episode 4 of The Last Independent Automaker, which focuses on the development and production of the AMC Pacer–a vehicle that even the most strident AMC enthusiast will admit caused a lot of problems for the company.

Here, I’ll examine what I think were some of AMC’s biggest mistakes and how some of them could have been avoided. This isn’t an exhaustive list, and some of it is subjective, but I think the conclusions are worth sharing.

Stages of Decline

Around 2016 I read the insightful book, How the Mighty Fall: and Why Some Companies Never Give In, by Jim Collins. Although not specifically about cars, it provides a data-backed framework of why and how successful companies fail. Collins and his research team broke down corporate failure into five stages of decline:

- Hubris born of success: Corporate arrogance creeps in during profitable years, and management starts to assume that because they were right in the past, they’ll always be right in the future. Success is seen as a given and not the result of hard work and discipline.

- Undisciplined pursuit of more: The successful company begins to expand faster than it can afford: hiring too many people, ramping up production too quickly, jumping into untested markets, spending too much on overhead, building fancy new offices, etc. Costs spiral upward, leaving the business dangerously exposed in the case of a downturn.

- Denial of risk and peril: When the hard data starts to suggest there is a problem, management finds ways to “explain it away” and blame it on external factors. For example: “The economy is just bad this quarter,” “gas prices will eventually come back down,” “Japanese cars are just a fad.” The lack of introspection prevents real problems from being addressed until it’s too late.

- Grasping for salvation: When reality finally catches up and throws the business into legitimate, undeniable decline, the knee-jerk reaction of bad management is to find a silver bullet that will fix everything overnight, like a new CEO, a hot new product, a new corporate strategy, or a new merger. Such changes are exciting, but rarely include the boring, incremental, necessary discipline required for sustained success. Decline doesn’t happen overnight and neither does recovery, but gambling the entire company’s future on a single person, plan, or product can be deadly.

- Capitulation to irrelevance or death: Having wasted precious time and money lurching back and forth after silver bullet solutions, the company hits the financial reality that it can no longer operate independently. Management makes the conscious choice to give up, and the company either has to be sold, go bankrupt, or go out of business.

Interestingly, Collins said that the stages are not a one-way street. Companies can spend years or even decades flipping between stages one through four as they ebb and flow. It is only at Stage 5 that a business reaches the point of no return.

These insights from How the Mighty Fall felt like a pair of X-ray goggles; suddenly, these same stages of decline were visible at American Motors. From its founding in 1954 to its purchase by Chrysler in 1987, AMC’s history was full of peaks and valleys, triumphs and tragedies. It was only when the company had to sell itself to stay alive that it truly died.

Mistake 1: The NOW Cars

If you’ve watched Episode 1 of our documentary, you know that George Romney pulled off a magnificent turnaround at AMC in the late 1950s by filling a market niche the Big Three had missed: economical, efficient, compact cars. AMC’s various Rambler models were smaller than their American competition but bigger than foreign European imports. They were not super glamorous, but they were profitable.

Romney did make some missteps during his tenure, but perhaps his (and AMC’s board’s) biggest was choosing the wrong successors when he left the company in 1962 to become governor of Michigan. In his place, Richard Cross became chairman, and Roy Abernethy became President and CEO.

As the former VP of sales, Abernethy had been with Romney on the “front lines” of the compact car crusade, helping AMC dealers turn Ramblers into best-sellers. By all accounts, Abernethy was instrumental in AMC’s turnaround, but as we explain in Episode 2, once he was in the driver’s seat he made a big U-turn.

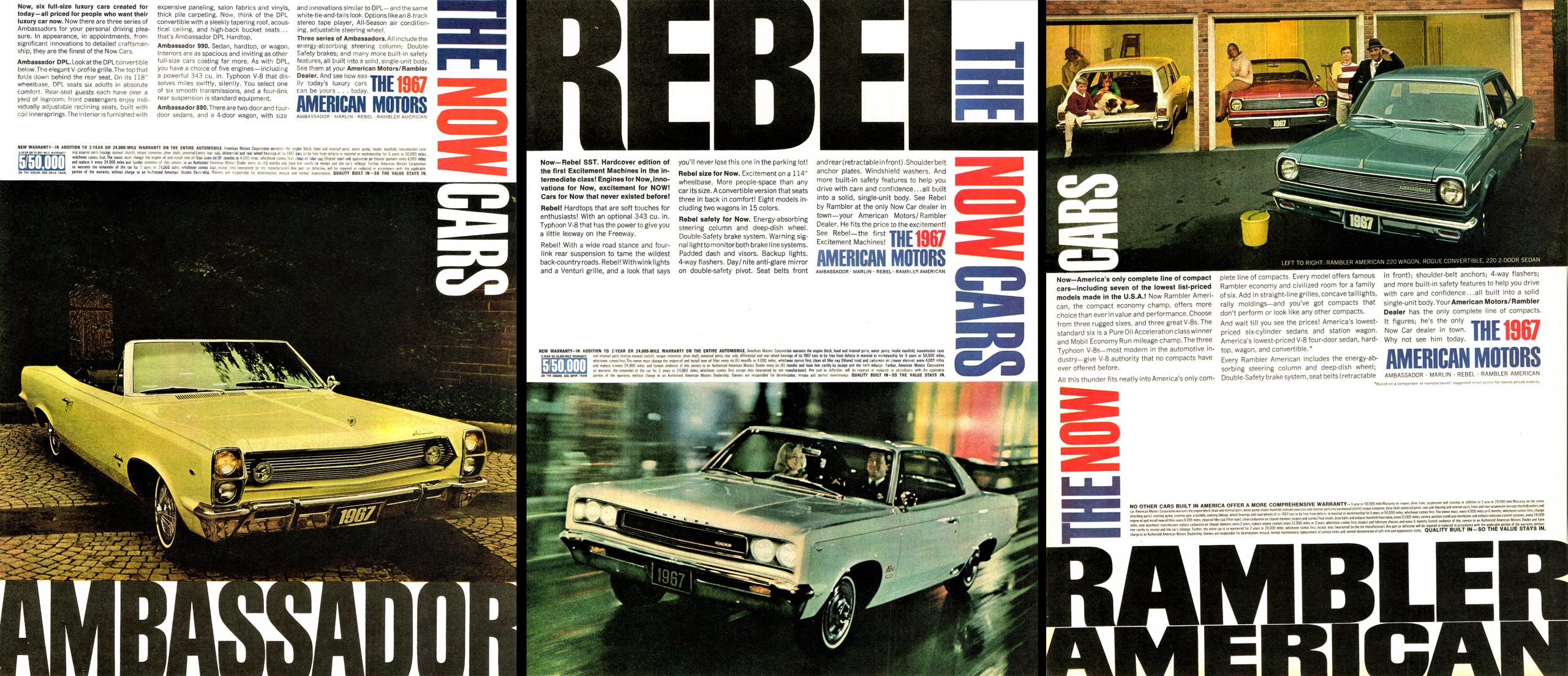

Romney had left just the company as the Big Three were invading AMC’s compact car niche with the Plymouth Valiant, Ford Falcon, Chevy Corvair, and Chevy II. Rather than double down in the Rambler’s core market, Abernethy instead tried to move the company upmarket with larger, fancier cars. The new models were beautiful (the ‘65-’66 Ambassador is a favorite of mine), but the tooling costs for the new bodies and frequent styling changes were huge.

Abernethy also botched AMC’s entrance into the performance car wars by insisting the new Marlin be large enough to seat 6, instead of copying the compact Mustang’s 2+2 design. Simultaneously, AMC’s smaller Ramblers were rapidly losing market share to Volkswagen and other foreign imports.

As a result, AMC missed the emerging pony car market, squandered its lead in the compact car market, and failed to establish a serious foothold in the luxury market. With rising costs and falling sales, Abernethy forged ahead with even larger redesigns for 1967, which some AMC managers quietly called “Roy’s cars” to distance themselves from them.

Again, sales were disappointing, and 1966 became AMC’s first year in the red since 1958. As a result, AMC’s board forced Roy Abernethy into “early retirement” in 1967. (To his credit, he did approve production of the 1968 Javelin and AMX before he left.)

Looking at the stages of decline, AMC came dangerously close to Stage 4 during the 1960s.

Stage 1: Management’s hubris was high after the magnificent 1950s turnaround …

Stage 2: Which fueled Abernethy’s undisciplined gamble to abandon AMC’s successful core business to pursue something unproven …

Stage 3: And when the new models floundered, management responded not by reversing course, but by pouring more money into even bigger cars.

I do not think Roy Abernethy was dumb or unqualified, and he faced a very challenging market during a time of great industry transition. I think he made some foolish mistakes, however. There are many AMC enthusiasts (especially Rambler enthusiasts) who think George Romney should have stayed at the company forever. Such wistfulness is understandable, but not realistic. Men who run for president of the United States would not be satisfied staying on as president of Detroit’s smallest automaker. Plus, there is no guarantee AMC would have continued to prosper had he stayed. It’s probable that Romney would have missed the pony car market also, not by building larger cars instead, but by resisting increased performance and horsepower.

My Suggestion: At the critical turning point in 1962, I think American Motors should have doubled down in the economy market and worked hard to increase its volumes and reduce overhead costs. Simultaneously, it should have carefully waded into the pony car market with a vehicle like the compact Rambler Tarpon, the concept car that inspired the larger Marlin. While the rest of the Big Three would have spent their resources on muscle cars, American Motors could have entrenched itself as a leader in the compact segment and perhaps been better prepared for the rise of Volkswagen and Japanese imports during the 60s and 70s. It wouldn’t have been glamorous, but it could have worked.

Mistake 2: The Pacer (and Matador and Wankel and…)

By the early 70s, AMC offered a full lineup that essentially matched the Big Three model-for-model, which–as past experience showed–was a costly and risky move. But as we explained in Episode 3, one difference from Abernethy’s strategy was that these models shared more parts and body panels between them, keeping tooling costs down despite AMC’s lower volumes.

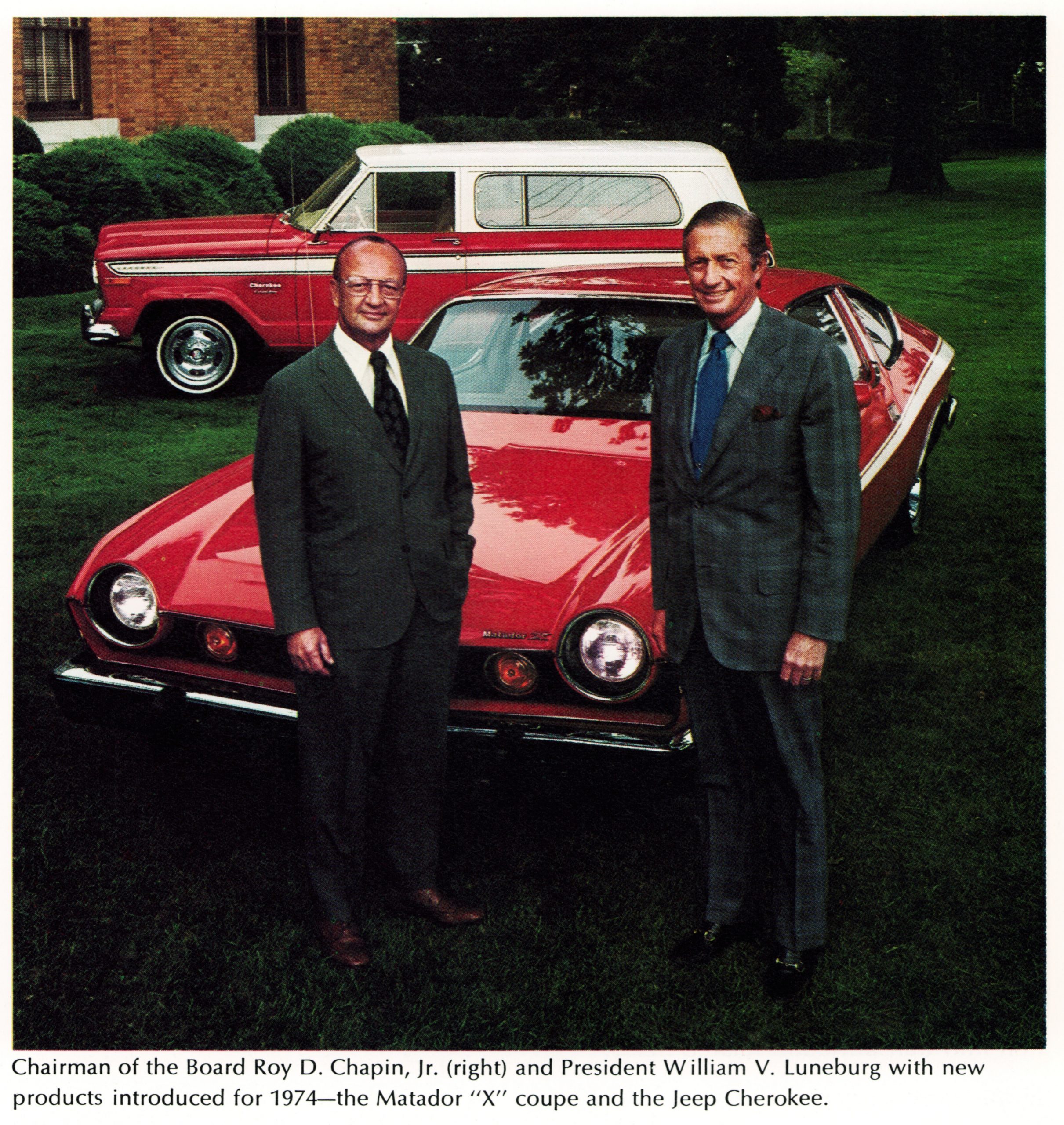

But after a few years of this strategy, AMC abandoned it again with two bold mistakes: the Matador Coupe and the Pacer.

The 1974 Matador Coupe was the company’s attempt to cash in on the booming personal luxury car segment with an ostentatiously styled two-door. The old ‘73 Matador Coupe had shared a lot with the Matador sedan and wagon, but the redesigned ‘74 model had an all-new, completely unique bodyshell that couldn’t be adapted into a 4-door. While sales of the coupe did increase significantly, they did not offset the tooling costs for a completely new car–especially one limited to just one bodystyle. Having been launched into a crowded market with unconventional styling, Matador Coupe sales soon faltered while customers bought Chevy Monte Carlos and Oldsmobile Cutlasses in droves. (Which is a shame, because the Matador is a cool-looking car.)

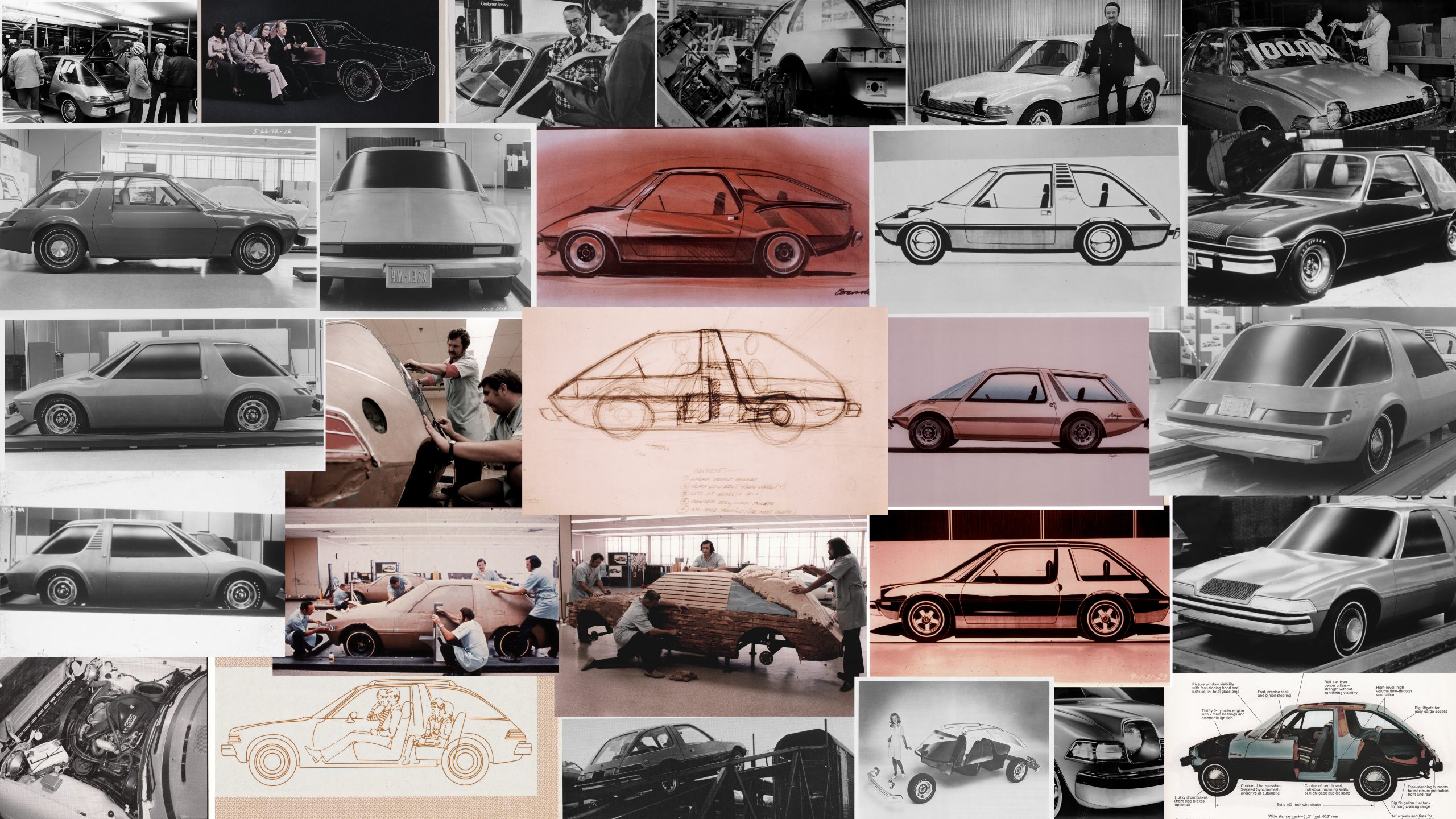

This mistake was repeated with the 1975 Pacer, which was another car that shared no body tooling with existing models. I’ve covered the Pacer story in two separate documentaries, so I’ll give the abbreviated version here:

Intended to be a futuristic commuter vehicle with the noble goal of maximizing occupant space while minimizing exterior size, the Pacer was supposed to be powered by a new Wankel rotary engine that AMC would buy from General Motors, until GM delayed and eventually cancelled the program after problems with fuel consumption and emissions. This forced AMC into a costly redesign, shoehorning its heavier cast-iron inline six into the Pacer. This required heavier brakes and suspension, which had a cascading effect on weight, which was made even worse by the car’s huge, heavy windows. (Glass being heavier than steel.)

Unlike the Matador, the Pacer had no direct competitors. “The First Wide Small Car” was billed as an alternative to cheap subcompacts and compacts and was a big hit at first. Unfortunately, the excitement didn’t last, as the car’s room and comfort were quickly overshadowed by its poor gas mileage (a result of the excess weight) and unusual styling. Sales began to slide and never recovered. AMC had plans to expand into more Pacer variants to help spread tooling costs, but the only one that came to fruition was the Pacer station wagon in 1977, and that wasn’t enough to reverse its fortunes.

When you zoom out, the Matador and Pacer were part of a larger spending problem at AMC during this era under president Bill Luneburg and Chairman/CEO Roy Chapin Jr. Their successful rebranding of AMC with the Javelin and AMX in the late 60s, combined with the success of the Gremlin and Hornet during the 1973-74 oil crisis, had fueled a false sense of security that American Motors could do no wrong.

Not all of their splurges were foolish; buying Jeep in 1969 was probably the greatest decision AMC ever made. But other choices, like expanding production capacity, hiring scores of new employees, and investing in costly new car designs, all caused significant increases in overhead. As overhead rose, so did the number of cars AMC had to sell to stay profitable, leaving it more exposed to danger.

The money spent on Pacer, Matador, and other projects kept American Motors from reinvesting in its bread-and-butter Hornet and Gremlin lines, meaning when sales collapsed in 1977, the company was caught with an aging lineup and no capital to redesign it–driving it into the arms of the French automaker, Renault.

Applying our framework, we see:

Stage 1: False confidence caused by the success of the Javelin, AMX, Hornet, Gremlin, and generally good years in the early 70s.

Stage 2: Expanding production, splurging on new acquisitions, and pouring money into designs that didn’t share tooling with other models, and gambling on unproven Wankel technology.

Stage 3: Ignoring that Hornet and Gremlin were getting stale (both had gone 6+ years without a major refresh) and overlooking the Pacer’s weight and gas mileage problems while in development.

The Matador and the Pacer were bold, creative, and even enjoyable cars. But they did not return the profits AMC expected, and their effect on the company was detrimental.

My Suggestion: I think the most heartbreaking part of the Pacer story is that AMC almost took a different path. In 1971, when product planners first greenlit the Pacer program, one of the runner-up proposals was a compact luxury car, which eventually became the 1978 AMC Concord. Built on a shoestring budget, the Concord was little more than a warmed-over Hornet with velour seats and added sound insulation–yet it was a moderate success.

However, if management had chosen the Concord over the Pacer in 1971, not only could AMC have invested more money in the design, but the car would have debuted three years earlier. As a result, it would have beaten the Cadillac Seville to market and gone toe-to-toe with the new Ford Granada. Both the Seville and Granada proved America wanted downsized luxury cars, and AMC could have ridden that wave, instead of jumping in after it. Concord would have shared tooling with Hornet and Gremlin, leaving AMC more money for important jobs like developing a new 4-cylinder engine, revamping Jeep products, and refreshing its other models.

In addition, management should have avoided building the Matador coupe and instead combined the Matador / Ambassador into one line for 1974. AMC was never going to be a major player in the mid-size/full-size car space. The Concord could be a mini personal luxury car and attract those buyers, while the combined Matabassaor line could just exist as a participation model for folks who were determined to own a large AMC. More importantly, I would have never approved the disastrous ‘74 Matador coffin-nose grill and instead kept the much handsomer ‘74 Ambassador front end, which bizarrely only lasted one year.

Mistake 3: The French Disconnect

When Gerald Meyers became CEO of AMC in 1977, he was handed a company in trouble. He saw the best way out of that trouble as building an all-new front-wheel-drive subcompact like the rest of the industry, despite the segment having grown hyper-competitive with very thin margins. AMC had squandered its lead in the small car market during the 1960s, and it had squandered the capital needed to regain it in the 1970s. Now, its only hope of building a new small car was through an outside partner. But while GM, Ford, and Chrysler had European operations with small car experience, plus ownership stakes in Japanese rivals like Isuzu, Mazda, and Mitsubishi, American Motors had neither of those advantages.

At some point in the mid-70s, AMC began shopping for a foreign partner, meeting with Peugeot and even Honda. After Gerry Meyers took over, he ultimately signed a distribution and manufacturing deal with Renault in 1978. As a world leader in front-wheel-drive cars with a desire to grow in the U.S., it seemed like a perfect match. But if you’ve read my previous story on the topic, you know their marriage was… troubled.

What’s interesting is, the AMC-Renault matchup originally was meant to be just a partnership, not a financial merger. It wasn’t until the 1979 oil crisis caused Jeep sales to collapse that Renault bailed out AMC by buying 46.1% of the company.

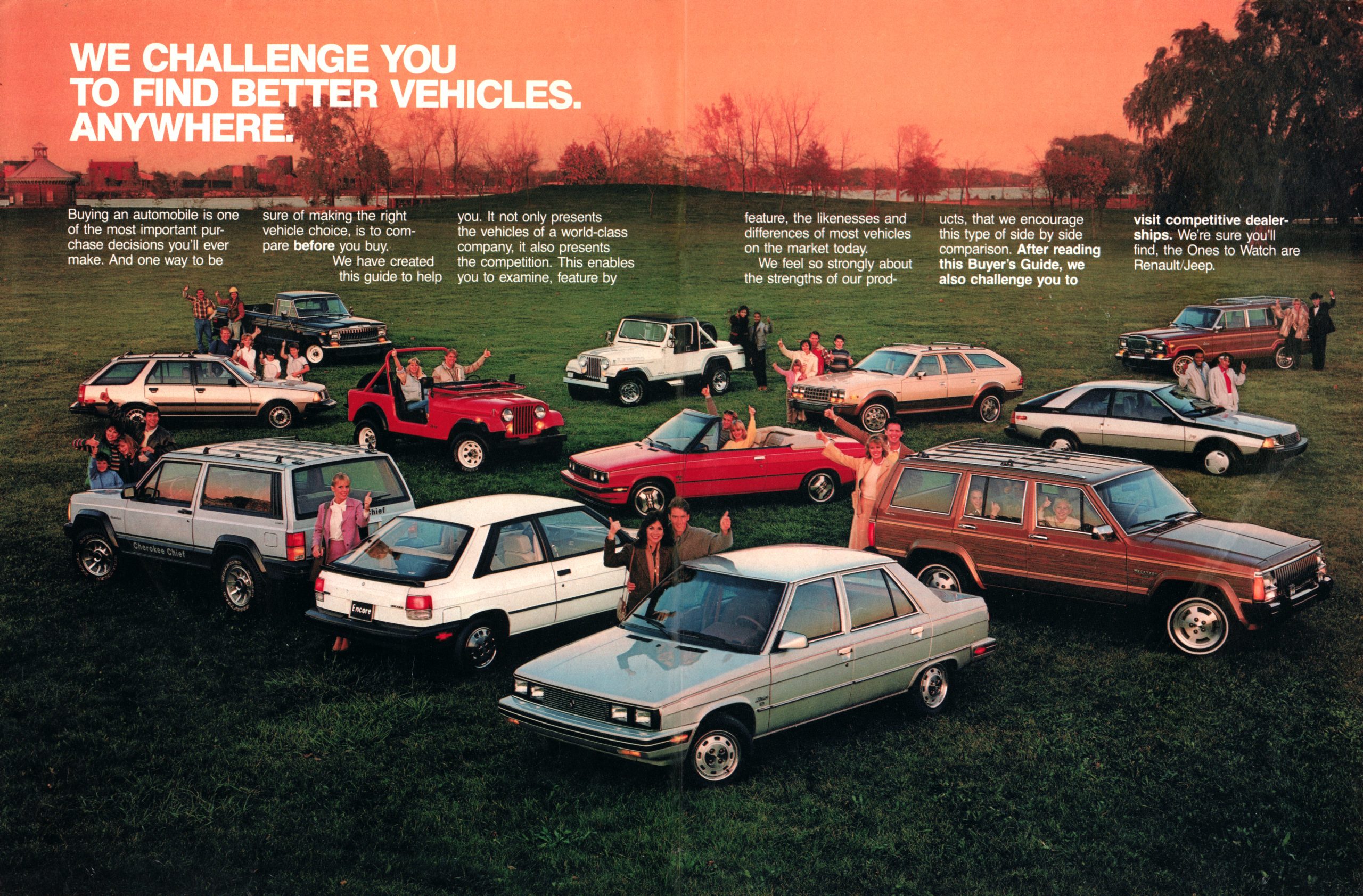

From there, the French slowly took over and forced Meyers out. As we explain in Episode 5 and Episode 6 of our documentary, things in the early 80s got pretty dire, with Renault spending $200,000,000 to bring the new American-made 1983 Renault Alliance subcompact and the new 1984 Jeep XJ models to market. With sales down across the board, Renault and AMC pinned all their hopes on these two products.

Both were initially hits, but only the XJ had real staying power. Whether imported from France or built at AMC’s Kenosha plants, Renault learned too late that their cars were all just a little “too French” and a little too unreliable for American drivers. When gas prices receded in the mid-80s and buyers flocked back to full-size cars, AMC and Renault found themselves stuck with a lineup of only small cars, in a shrinking and intensely competitive market. No amount of Jeep profits could offset the losses from the car division, leaving AMC and Renault to pin their hopes once again on another new product, the upcoming Renault Premier mid-size sedan. But before the Premier could arrive, political unrest in France forced the automaker to sell its share of AMC to Chrysler in 1987, and Lee Iacocca was all too happy to acquire AMC and its legendary Jeep line for a cool $2 billion. AMC was gone.

Looking at our framework, Meyers took the reins when AMC was deep into Stage 3: denial and cresting Stage 4: grasping for salvation. In How the Mighty Fall, Jim Collins warns that companies in desperate situations can often react like a drowning person thrashing around in the water, i.e., their erratic behavior can unintentionally make the situation worse, not better. That’s not to say that companies in desperate times shouldn’t take bold moves. Rather, it’s that a desperate company should take calm, disciplined steps to avoid disaster.

Instead, AMC began grasping:

Grasp 1: Seeing a new subcompact as the best way back to prosperity (despite the market segment having notoriously thin margins) and seeing a foreign partnership as the only means to it.

Grasp 2: Partnering with a French automaker that had little experience in the U.S. and a poor understanding of the U.S. market.

Grasp 3: Pinning the company’s hopes on just two models, one of which (the Alliance) was arriving late to the hottest, most competitive segment of the market.

Grasp 4: When the Alliance (and its hatchback variant, Encore) didn’t pan out, the companies then pinned their hopes to the mid-size Renault Premier, which–like the Alliance before it–would arrive late to what was then the hottest segment of the market.

Interestingly, one of those grasps, the XJ, turned out to be a big hit! But its success was overshadowed by the collapse of Alliance sales in 1985. This only furthers the point that one silver bullet is rarely enough to save a company. It takes several hits in a row.

My Suggestions: Like Roy Abernethy, I don’t think Gerald Meyers was dumb or unqualified. Having actually met the man, I was impressed by his wisdom and candor. He was handed a tough situation and – had it worked – his plan for the Renault partnership would have actually made a lot of sense. And without Renault, we would have never gotten the Jeep XJ!

Given how things all turned out, I wish AMC had partnered with Honda in the late 70s instead. Unlike the French, the Japanese worked hard to understand the American consumers and adapt their products for that market. If AMC and Honda had entered a manufacturing agreement, AMC’s Kenosha plant would have been working overtime to build Accords and Civics, and possibly rebadged AMCs. Pairing Honda’s lineup with Jeep’s offerings, dealers would have had a field day.

Sadly, I can’t really figure out how serious the negotiations ever got. Information is incredibly scarce, and any of the executives who would have been involved with those discussions have passed away. So while the daydream may be exciting, it’s possible that things never progressed past a few meetings.

But there was an alternative choice to Meyer’s plan that was a lot more realistic, and it didn’t involve building small cars … or any cars, actually.

I recently wrote an alternate history imagining if marketing executive Bill McNealy had gotten the top job at AMC instead of Meyers. In 1977, McNealy wrote a remarkably clear-eyed proposal where he insisted AMC should leave the passenger car business entirely and focus all of its resources on building Jeeps. He argued that the compact and subcompact segments had become so dominated by the import brands that AMC didn’t have the technology, capital, or volume to make any money in those markets. Instead, he suggested selling the passenger car operations as a tax write-off and pouring resources into a new fuel-efficient Jeep for 1981.

With a downsized fuel-efficient Jeep arriving in the midst of the 1979-80 oil crisis, AMC would have one of the only compact SUVs on the market. Having sold its passenger car business, the massive overhead and losses from that division would have been gone. To keep dealers happy, McNealy advocated that AMC sign distribution deals with a handful of import brands, which would be much less capital-intensive than a manufacturing agreement. It was a bold plan, based on empirical evidence, and would have required extreme discipline to execute. But it could have worked! Sadly, AMC’s board was too scared to abandon the passenger car business, and they ultimately chose Meyers to lead the company.

Of course, McNealy’s plan was not without flaws. Without Renault’s capital and technology, would the Jeep XJ have been such a world-beater? And while an independent Jeep would have dominated the SUV market in the 1980s, would it have been crushed when the Big Three threw their full weight into the game in the 1990s? Or, Jeep being the invaluable brand that it was, would a larger automaker have scooped it up anyway? It’s impossible to know.

They Say Hindsight’s 20/20…

As I said at the beginning, our team had to walk a fine line when making The Last Independent Automaker. It’s lazy and inaccurate to paint American Motors as a victim of circumstance, with no control over its fate. The company made real mistakes. On the other hand, I don’t want to judge AMC management too harshly. As historian David McCullough points out, people in history didn’t know they were living in historic times. Unlike us, they didn’t have the advantage of knowing how everything turned out. Had I been in Roy Abernethy’s or Roy Chapin’s or Gerry Meyers’ positions with the information they had at the time, I don’t know if I would have done any better.

One reason why automotive history appeals to me so much is that I think it has valuable lessons for the present. If I told you I just made a documentary about the automotive industry undergoing rapid changes from new technology, globalization, automation, environmental regulation, economic recessions, and a spike in interest rates, you’d think I was talking about today, not 50 years ago! The lessons from American Motors, what it did right and what it did wrong, are still relevant.

And that’s why I’m so proud that my friends and I got to tell this story.

The Last Independent Automaker is available to watch now on YouTube, the PBS app, and on Public Television stations around the country.

The series is distributed by American Public Television. Maryland Public Television is the presenting station. The Automotive Hall of Fame provided fiduciary assistance. The Last Independent Automaker is funded in part by Visit Detroit, The Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and MotorCities National Heritage Area. It is also funded by over 375 individuals and organizations who contributed through the project’s Crowdfunding campaign.

Top graphic images: AMC / The Last Independent Automaker

So Chrysler has just been in a continuous cycle of all those steps for the last what, 40-50 years?

Ive always been fascinated by late-era AMC, i stumbled across this training laserdisc years ago and posted it on the tubes of you…. its brutal.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UYAzHS-xYss&t=0s

The hairstyles! The fashion! The terrible camera angles! (I’ve never spent so much time looking at the back of someone’s head as they are talking). This is comedy gold.

The Kids seem to think the 70’s and 80’s were amazing to live through; this video shows the unvarnished truth.

As a kid who grew up in Michigan and a prior owner of a Renault Alliance and just a general geek on automotive history, I want to say how grateful I am for your documentary.

Your interviews and thoughtful analysis are a master class in how to present the rise and fall of a company. Throughout your story, what I noticed most was “people,” not vehicles.

Thanks so much.

I liked the AMX, Javelin and Rebel. They should of stuck with those.

The Honda angle is fascinating to speculate on, most of all as owners of the Jeep brand. It might also have kept them from teaming up with Austin Rover and being royally shafted by the Thatcher government and British Aerospace.

At least they’ve got a lot of company in the “fucked by Thatcher” club.

The Matador Coupe has always played mind games with me. I never cared for it, but for some reason I want to like it. Maybe because it’s a big coupe, maybe because it’s different. It’s a car I would never pick, but I feel sorry for it.

It’s one of those cars that looks good at a certain angle on a particular day in a specific color, but from every other angle it’s just terrible.

The author of this article says he thinks the Matador coupe looks cool. I have to disagree. But, I looked up pictures of a ’74 Cutlass and it wasn’t any better. Olds lost the plot in ’73, when they went from quad headlights to those ugly 7″ abominations.

I feel like AMC was uniquely vulnerable to the Beetle because of their primary market position, so I’m not sure throwing all of their eggs in that basket would have saved them any more than Renault’s money 20 years later did.

As an AMC aficionado and lover of all the goofy products they made, this article is fantastic! AMC certainly were getting high off their own supply in the mid 60’s which is quite funny considering they were the 4th auto maker to the Big 3 and certainly didn’t have the success to warrant the arrogance they had.

I will say I think AMC could have been saved in another way. AMC wanted to build cars for all buyers at all price points, and I argue they should have continued to do so in a cost cutting way that consistently offered more for less. AMC was the first to have A/C standard, do it across the line. AMC made the same car 5 different ways? Do it for all of your cars. The Taco Bell approach was what made AMC profitable in the early 70’s, crank it up to 11!

Take the Hornet, you could do a 2 door coupe, hatch, and convertible along with a 4 door sedan, hatch, and wagon. Your most expensive bits would be the convertible and wagon, so use the Wagon extended rear fenders for the convertible and you’ve got room for the soft top. Integrate the motor and drivetrain from Jeep and sell that as a “Honcho” in all the same body styles. You can sell 12 different vehicles from one single frame and shared drivetrain.

You sell all of those for less than a Pinto or Vega with more standard features because the cost will be reduced by every vehicle getting the same standard feature. AMC buyers can only pick their color, body style, transmission and dealer added features. Find every vehicle market that you can fill and undercut those sellers. Who cares if quality isn’t up to Japanese compacts when you get more features and a decent warranty? It’s the Kia approach 30 years sooner.

Now I’m sure you’ll say “Well they did that and still failed!” They failed because of the cars they built that didn’t take this approach. When it comes to the late 70’s and early 80’s, the nut up or shut up approach with engines and FWD drivetrains would have been the point for AMC to abandon their drivetrains and find someone that they could make engines with. After all, AMC bought the Fireball V6 engine tooling from GM before selling it back to them in the 60’s. Imagine AMC working with Honda or Renault to make the engines and transmissions under license here in the US. Hell they might still exist, selling Wranglers and Grand Wagoneers next to cheap and cheerful Hybrids and EV’s.

They should have made the Eagle Wagon 4×4 earlier. There was a huge market for quirky cars that could drive in mud and snow. How big? About the size of Subaru.

Glass is not heavier than steel. Glass 150 pounds per cubic foot, steel 500 pounds per cubic foot.

you are forgetting thickness. standard auto glass is .25 inches thick. and weighs 3.24 lbs/ft^2 20 Gage Steel weighs 1.5 lbs.ft^2

While the windows were big, how much bigger were they than standard windows for the time? Even at 10 sq feet more, that would only be 32.4 lbs more. I think the engine weight (and other necessary updates due to that) were a lot more relevant, but honestly the Wankel (especially back then) isn’t know for fuel efficiency, either.

I think a big problem is compared to the big 3, AMC cars post ~70 were hideously ugly.

The Pacer had 39 square feet of glass, which was considered to be 50% more than the typical subcompact of the era

That worked in combination with the plan to future-proof the car against the worst case scenarios for crash testing that were being discussed for the 1980s, resulting in an unusually rigid, for the time, passenger cell with reinforced roof and bulkheads and heavy side intrusion beams.

It all added up to a curb weight of 3,000lbs for a base model, and over 3,400 lbs with air conditioning and automatic transmission – in comparison, the one size larger Hornet was 2,917 lbs and the two sizes larger Matador was 3,754lbs. AMC’s other subcompact, the Gremlin, which had 4 inches less wheelbase but was only 1.5 inches shorter overall, was 2,633 lbs

And a very large percentage of 1975 and 1976 Pacers did have a/c and an automatic, since it was initially pitched as a luxury small car and was initially purchased mainly as a fashion accessory for its unconventional appearance vs it’s practical attributes

The Pacer was almost same size class as the Hornet when accounting for all dimensions. The Pacer was taller than the Gremlin/Hornet and also a whopping 6 inches wider. That’s a huge difference and helps explain the extra heft, even beyond the glass. The Hornet–in all its body styles–was also the same width as the Gremlin… 70.6.

That’s because the Gremlin was a cut down Hornet, the Pacer started out by the designers taking the front seats and footwells of an Ambassador, putting them on the ground, and using chalk to trace out the absolute minimum dimensions that could enclose them and a drivetrain, no joke, that’s how it was conceived, much like the Gremlin being sketched out on a barf bag. The whole premise was fitting full-size front seat room within an otherwise subcompact vehicle

If only they had done so with just $12 million, like the Gremlin. Instead, at $60 million, they had an albatross when sales faltered in ’76.

Honestly, the Pacer is a good example of the sunk cost fallacy – it should have been cancelled either when GM pulled out of the rotary program or when the 1973 oil embargo effects really took hold, which were pretty close together, but separated somewhat on the timeline. But, then, the over 145,000 sold in the first calendar year gave them a major false sense of security early on (it was the first new product in the history of American Motors and all of its predecessor companies to exceed 100,000 sales in its first year on the market). But then, everyone who wanted one got one, and it all crashed and burned from there

Am I the only one who thinks that, maybe, this was GM’s plan all along, the leave AMC high and dry? Or have I watched “Tucker” too many times?

Yes, yes you are. AMC had totally different issues from Tucker, they didnt have a failed IPO, cancel all orders at their aircraft engine subsidiary, triggering lawsuits from customers, lease a factory vastly larger than they could fill, and hire thousands of plant workers at least a year ahead of when they’d have any actual revenue to pay them

At any rate, AMC had also taken out their own, separate license on the Wankel design and had planned to transition to building their own rotaries in-house at some point

And, as we all know, the rotary would have been an even bigger disaster in the Pacer than the straight six, had it actually gone into production. The car would have been lighter and performed and handled better, but would have gotten even worse fuel economy and been even harder to get through emissions, not to mention the apex seal issues that nobody really solved on rotaries until Mazda several decades later

Karma got them nicely when the Citation hit the street in 1980.

I think you are giving GM leadership too much credit.

Although they did a decent job of infighting between brands, so maybe…

I believe sales of the Hornet topped 100K (barely) in 1970 and sold at steadily above 100K until the Pacer arrived. This success I’m sure convinced AMC it could continually thrive in the compact segment.

I’m not sure the Pacer should have been cancelled. Sales in 1975 and 1976 proved that AMC was correct in responding to the oil crisis with an efficient city vehicle that wasn’t the maligned Pinto/Vega. The Pacer’s biggest year, 1975, corresponded to the worst year for U.S. auto sales in the 1970s. WIthout the Pacer AMC would likely have seen poor sales in general. Unfortunately, when the crisis was over buyers went right back to big traditional cars, and when the next gas crisis arrived in 1978-79, the Japanese were there to compete.

What AMC should have done is riffed off the basic design with a more conventional Pacer-based sedan/coupe (or even a van!) to take advantage of all the engineering that went into the car. Most of the last Pacers sold were wagons… people simply wanted more car for the money. Make it look an Olds Cutlass and rake in the sales.

Once it was in production, sure, but I think there were warning signs during development that the product was going to be too compromised to properly serve its intended niche, so someone should have stopped it then and maybe redirected the funds toward further upgrades to the Gremlin and Hornet

Great read, and I’ve said before that it’s one of my fav documentaries, very well done and totally made me want to get a Spirit AMX (not that I did haha).

Tesla sure does seem to be going down those 5 steps.

Tesla even came up with their own bonus step where the CEO gets addicted to ketamine and makes the brand radioactive by shit posting and endorsing fascism.

Also, Tesla is a $1 trillion company that has somehow structured themselves around being able to work on only one project at a time, that’s why their model range is old as hell, the Roadster still isn’t out, the restaurant in LA took years to build, and the Semi barely exists. The weird thing is, they seem to be somehow proud of it on some level, being a company with more money than most countries that isn’t capable of multitasking. It very likely has to do with Elon’s microgement

I once looked at an ’81 Cherokee being sold by a co-worker (’02 or so). I saw an AMC 360 backed by a Chyrsler 727. The carb and ignition were clearly Ford. I think the brake booster/master cylinder and P/S pump were GM. I walked away from this parts mashup and bought an ’89 XJ Cherokee with a 4.0L. Renix only caused me one problem during my ownership.

89 still had a mashup of parts, though many of them were French instead. Except the auto trans in those was basically a Toyota A340H, so definitely a bump up in that regard.

Oh yes, but it at least seemed cohesive and designed in. It had the old Saginaw column for God sake. The ’81 seemed a mashup of whatever was available for sale by the Big 3 cheapest that year.

That’s true, but they were transitioning from a GM transmission to a Chrysler transmission across the board at the time. Jeep used the GM Steering column into the 90s at least – YJ’s still have them.

My feel on the ’81 was they took bids each year and bought what was cheapest. Zero integration, it all seemed an afterthought.

The XJ felt to be an actual engineered whole. I don’t fault the Saginaw column, it did it’s job.

I don’t think the 81 is anything special about them taking bids for the cheapest parts- there are lots of 76-77 only parts on my CJ-7, but the big changes (non-engine drivetrain stuff) they tended to stick with for a few years.

I just went full GM on my CJ7. 14 bolt out back, D60 GM side drop in front, K5 disc brakes front and back, SM465 4 speed connected to the 90 TBI 350 it was originally connected to. the steering wheel and column form the same truck fit without much trouble, probably because of the saginaw connection mentioned, and the stuff that needed to better? Atlas 4.3 Twin stick T-Case and lockers front and back. I did use the AC compressor to make a cheap onboard air system, but I think I will go to ARB before long.

I actually like my Quadratrac transfer case, so that means sticking with my existing AMC drivetrain. I have Moser 1 piece axles in the back along with a Detroit Locker and 4.10 gears, the Ford front brakes and bigger wheel cylinders in the back and a bigger brake booster to bring those 35″ tires to a stop. My 304 has a cam and a 4 bbl carb.

This – they were almost kit cars from the start. Swap in what works better. Part of me embraces this ethos, part wants to just run away. A big factor is use case. I wanted to turn that ’81 into a toy 4×4 runner. The cowl rust was the ultimate no go.

The ’89 interior cleaned up well, I resprayed the body in dad’s driveway after patching up the rust. It was a great cockroach of a car.

The great thing about using all of those parts is they were cheap and easy to find replacements for. My 76 Jeep had Motorcraft drum brakes and starter, a GM steering column, and GM Prestolite ignition and alternator. I was able to change the ignition to a Motorcraft one with a much better reliability, the alternator to a higher output Motorcraft one, and was able to easily swap from drum brakes to discs using Motorcraft parts. I also put a tilt steering column from a later model GM truck into it. Oh yeah, Motorcraft brake cylinder and GM power steering.

In 1981 everything was a mashup of parts from multiple suppliers that often didn’t work all that well. Example, the K5 Blazer got an SBC and TH350, but with New Process and Dana hardware just like Jeep. As well as a failure-prone electric tailgate glass mechanism, just like Jeep. At least with the Jeep you got unique 4×4 gear, like Quadra-Trac.

I never understood the Matador coupe as a kid. I thought, and still think, it is possibly the ugliest car ever made in America.

As an adult, I understand its recent renaissance/image rehab/neo-fandom even less.

I mean, just LOOK at that monstrosity. People actually like that? Actual people with eyeballs?

I think its handsome, better than some of the other lux coups of the era!

I guess this tells me that you’ve never seen a 1976 Pontiac Grand Prix SJ or a 1977 Thunderbird, much less a 1974 AMC Javelin.

Oh I have, even owned a 76 cutlass 442! but I think it looks handsome, all subjective natch.

The fact that Mikey on Orange County Choppers had to have one tells you pretty much all you need to know…An Oleg Cassini model no less.

The Oleg was perhaps the gaudiest trim I have ever seen on a car. My neighbor had one and it made my dad close the blinds whenever it was parked in their driveway.

Jeep is the parasite that eats its host. Instant profitability but long term woe.

I think another major problem AMC had was the Kenosha plant. They had a fairly new plant in Ontario, but the one in Kenosha was actually two buildings separated by a couple miles. They literally would build the car bodies, put a bunch of them on semi trailers that kind of looked like scaffolding, and then drive them over to the other plant to be finished. While it was endlessly fascinating to me watching it as a kid, that had to be the most wildly inefficient plant in North America.

The Brits were doing the same thing at the time, I believe all MG’s and Healey’s were trucked a few miles down the road in the winter from the body shop to the paint shop.

Britain. Winter. Unpainted car bodies. Wow, never guessed that factory rust was a thing.

That plant was outdated in the 1970s… I believe the building itself dated from 1902. But the main thing is that AMC just didn’t have money for robotic welding. Everything was done more or less by hand at much higher labor cost.

I will most certainly be watching the documentary. I’ve always felt that AMC’s biggest mistake was right at the beginning, by failing to get Studebaker and Packard into the fold. Without legitimate truck and luxury brands, AMC never really had credibility as a full-line manufacturer. My old man thought they were “a joke”, and never considered buying one.

Great article, love the history.

I don’t think any amount of deck chair rearranging could have saved AMC. They were just reshuffling their outdated designs. Chrysler almost didn’t survive either until the K car came along. They couldn’t continue to shoehorn their primitive, dirty and gas guzzling 6 and 8 cylinder engines into new cars and, if I’m not mistaken, they were using A904 and A727 Chrysler automatics anyway. There was no way they could have developed a transverse FWD engine and transmission layout with a platform to match, and that was wave of the future, to this day.

The day you introduce a new product is the day you start designing its replacement and innovate for the future and if you don’t do the work, you’ll forever be reacting to the market flat footed and two steps behind.

Ford thought they could be Tesla and rake in money. How did that work out? An inferior pickup and the Mach-E and little else. And now they’ve essentially given up and are just blaming external factors because they can’t take responsibility for their own poor decisions and management incompetence. At least Stellantis is taking the heat off them. Ford: King of the Recalls…

I always wondered why it took AMC until the 1980s to figure out they could essentially lop 2 cylinders off their straight six and make their own 4 cylinder with a lot of shared tooling- instead of buying in engines from GM or Volkswagen at inflated markup.

Was it just that they really didn’t have the budget at all in the 1970s, even for something relatively minor like that, or was it just that the idea absolutely didnt occur to anyone until later?

Or a cross flow cylinder head, an aluminum cylinder head, or a 6-cylinder engine that didn’t weight 700 lbs because it required all the cast iron in the world.

I think they actually did build some aluminum versions of their previous straight six in the early 60s, but decided against going ahead with it. Crazy they even spent that kind of money on a 1930s vintage Nash design that was already on its way out

A lot of ‘63 models had the aluminum version of the 195.6 six cylinder. They went back to cast iron in ‘64 due to reliability issues.

It wasn’t the budget, it was just a terrible decision. Actually, several terrible decisions… it was thought by AMC management that the Matador and Pacer would earn enough to allow AMC to downsize its products enough to make them work with VW’s engines.

In anticipation of this, and following the Wankel debacle, AMC’s management spent about $60 million licensing VW’s OHC 4-banger to produce it themselves. Unfortunately, the engines were just too small for AMC’s heavier cars and, in desperation, the Iron Duke was adopted.

No mention of Eagle? Or did I miss that? (sorry if I did.) I did see the Eagle vehicle in that last print ad. At the time, they looked more sophisticated than Subaru, but they lost that market, too.

Congratulations on producing an outstanding documentary on a shoestring budget! This article is first rate too!

When you’re drowning, you’ll grasp for anything that appears to be floating, but gosh, Renault was a poor choice. In the 1950s, the Renault Dauphine was the #2 selling import car in the USA, right behind Volkswagen. But by the time of the merger/acquisition, Renault was all but deceased in the US, mainly for the reasons you state about being unable or unwilling to bend to American tastes and needs.

Great article! I’m finishing a Masters degree in Management & Leadership (BS in Mechanical Enigeering). I’m a maintenance engineering manager and see these decisions play out in real time daily.

This is an amazing read. Thank you for sharing this, and thank the site for offering it.

I’ve never imagined a scenario with Honda and AMC as a partnership. I have to wonder how that would have turned out. It could have been epic, or it could have been the Sterling 800/Acura Legend debacle.

Ahh yes, Japanese design with Britsh reliability.

A friend in college had an ’88 Legend and it lived up to the name.

Q: What’s the difference between Heaven and Hell?

In Heaven…

the French are the cooks

the Germans are the engineers

the British are the police

the Swiss are the managers

the Italians are the lovers

In Hell…

the British are the cooks

the French are the managers

the Italians are the engineers

the Germans are the police

the Swiss are the lovers

I can go for many other cultures overall on the food front, but agree.

“the

GermansJAPANESE are the engineers”I’ve seen and read about too much ‘German engineering’. Give me the Japanese engineers instead!!

Let the Germans be in charge of delicatessens.

This is great. (And a new one to me).

1st job out of the Navy in 91 was a dealership that included Sterling. I had never heard of them, and remember customer cars either being piles of crap, or really fun examples to test drive. There seemed to be no in-between. (And yes, I remember some really fun test drives. Perhaps newer models.)

The 800 was only really a debacle in the US, the Rover badged version was actually a very strong seller in the UKDM, and, of course, the Legend worked out for Honda pretty much everywhere

Honda was interested in Rover’s expertise with larger luxury cars, as well as European manufacturing capacity. At the time the alliance was made, Honda wasn’t really interested in the 4WD SUV business and wouldn’t be for about another decade, so they wouldn’t have cared about Jeep in the 70s if they didn’t really pay attention to Land Rover until the 90s. Also, Honda didn’t really care about moving upscale with bigger cars until the Voluntary Import Restraint agreement hit in the 80s, so they wouldn’t have cared about AMC’s help in the 70s, not that AMC were subject matter experts anyway

The only thing AMC really had to offer was production capacity, but, even then, the Kenosha and Toledo plants were extremely inefficient and outdated and badly in need of capital investment, and Honda ended up doing well building from scratch. Which is also what AMC and Renault eventually did with the all-new Premier factory in Ontario

Honda built Marysville from a greenfield IIRC.