As a Powertrain Design Engineer, the first time you design a cylinder head is a huge challenge. You have to contain gasses at 1200°C (2200°F), coolant at over boiling temperature that can’t be allowed to boil, hot oil at pressures high enough to send a flammable jet across a room, and air passages that have to have minimum flow disruption despite being completely blocked by a valve 60 times a second. Plus all of that in a single lump that mounts the valvetrain, inlet manifold, exhaust system and anything else that’s nearby in one big complex casting, while being bent by thousands of explosions every minute. And oil drains, mustn’t forget oil drains (my very first job on a cylinder head was to add oil drains that the previous guy had forgotten – it’s a very complex part).

By the time you’ve designed a few (they can each take months or even year) and had several of them binned when projects got cancelled, it just starts to feel like routine work. What makes it feel even more just like routine work is that OEM’s have standards for everything, and often they are legacy habits from a time when there wasn’t CAD, or they used inches as a unit, or had lazy designers who weren’t exactly terrific.

[Dave Larkman is a mechanical design engineer who had a 25-year career at Lotus Cars and Lotus Engineering (the consultancy business that worked for other OEMs), eventually becoming Lead Engineer of Powertrain Design. He has also been a semi-pro drifter, rides sports bikes, and used to feel ashamed about his taillight collection until he found Jason Torchinsky on the internet. Wait, why am I writing this in third person? It’s me, Dave, writing my own bio. – DL [Ed note within ed note: Sorry, Dave. I’ve got a Jeep to fix and no time to write bios. -DT] ]

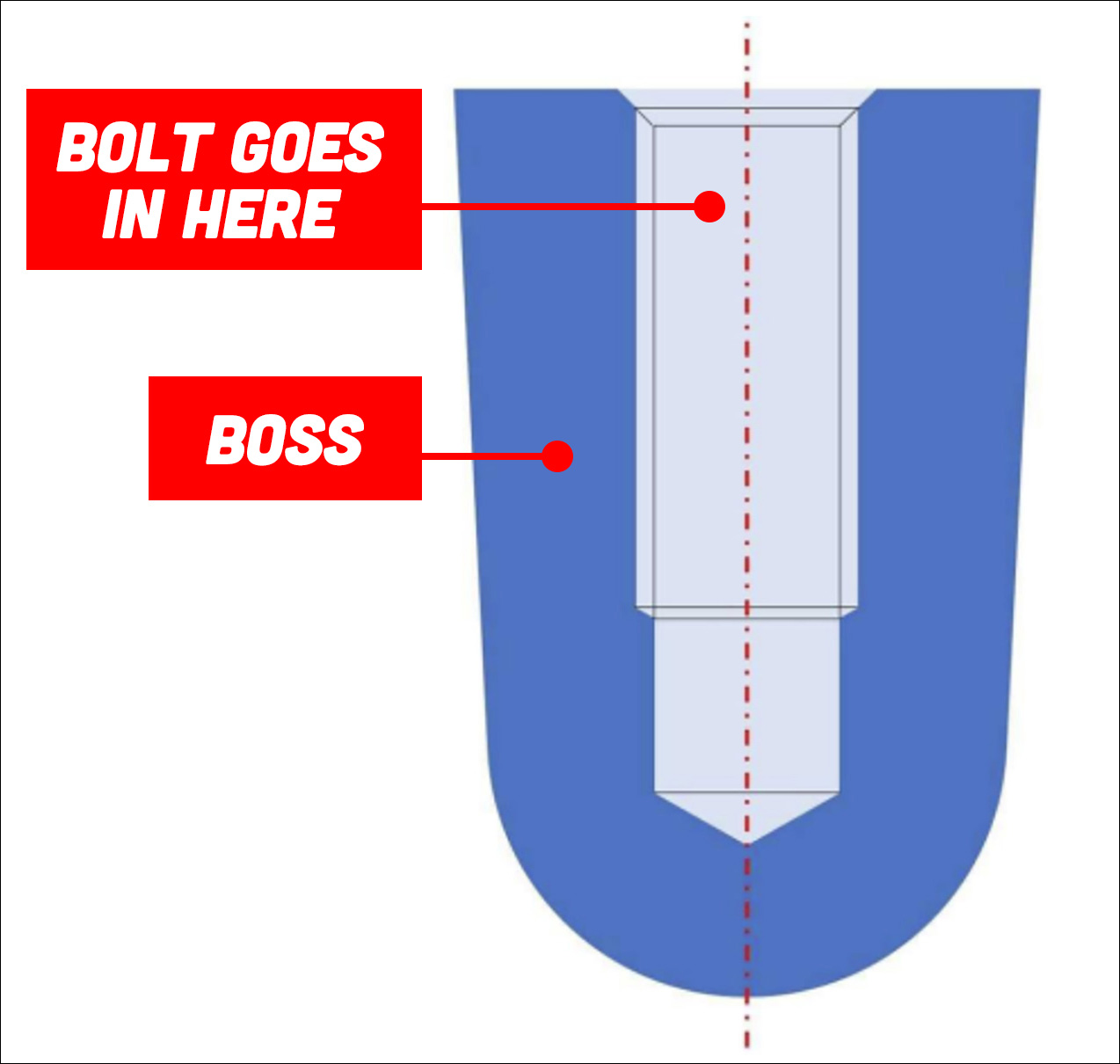

This particular project had a cast bolt boss-standard that was simple, logical, and boring. A bolt boss is any feature on a casting that you fit a bolt or a screw into (fun way to make engineers fight: ask them to agree on a definition of what makes either a bolt or a screw). You need the boss to be deep enough for the screw thread, which will have a minimum length based on the material and how it’s made, and wide enough to have enough material around it to not only be strong enough, but to not leak (castings can be a bit porous, and there is often an oil passage running right next to your bolts). All of that has to take into account the manufacturing tolerances on the tooling, the casting and the machining. So it’s low risk to just look up an M6 boss or whatever and copy the dimensions down.

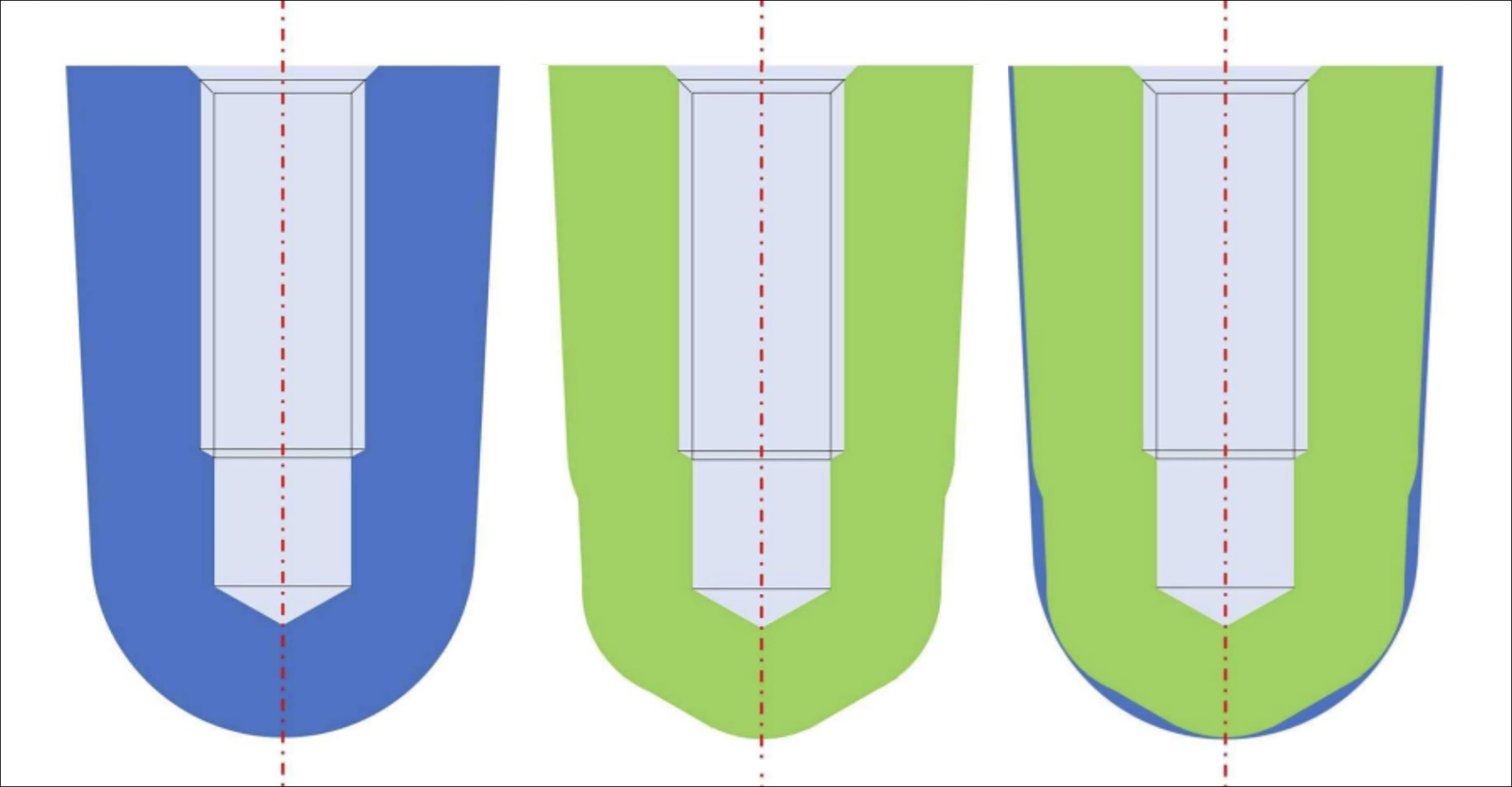

However, it’s a bit dull, because it’s just a slightly tapered cylinder with a spherical end, like this:

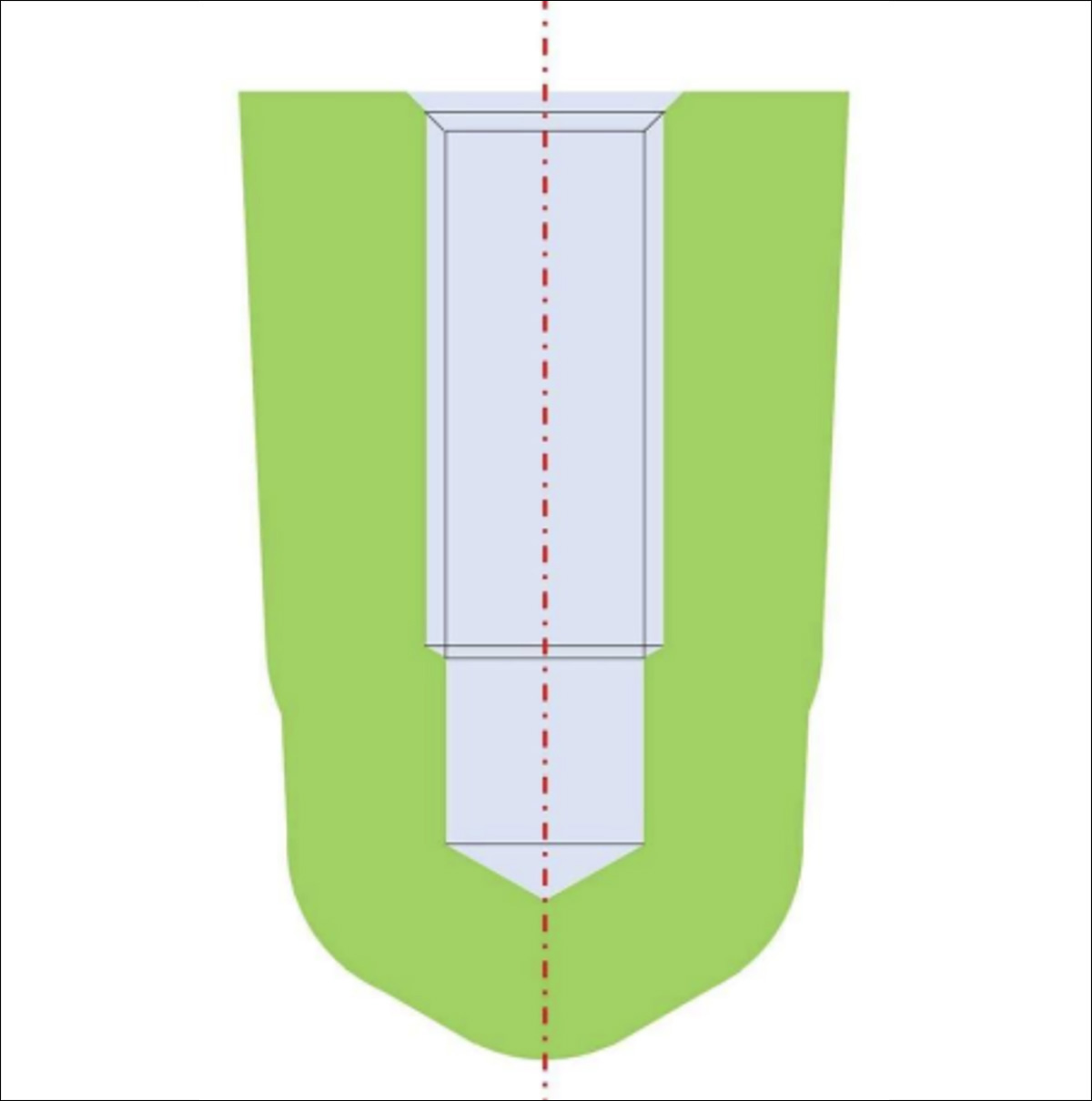

The actual machined feature is a drilled hole with a cone on the end, then a slightly wider, slightly shorter thread. I thought, why not take the minimum wall thickness from the standard boss and offset that from the feature I actually need? It’ll be no harder to make, but lighter and therefore cheaper, but most importantly it won’t be the same ball-ended blob I’ve been modeling for ages.

So I quietly came up with this pointy, stepped blob and threw it all over the place.

There was no justification for doing this; it was already under the mass and cost targets by enough to get a little pat on the head, and still chunky enough to zip through durability testing without getting a massive kick in the groin for failing and costing the client millions. But, you know, bored.

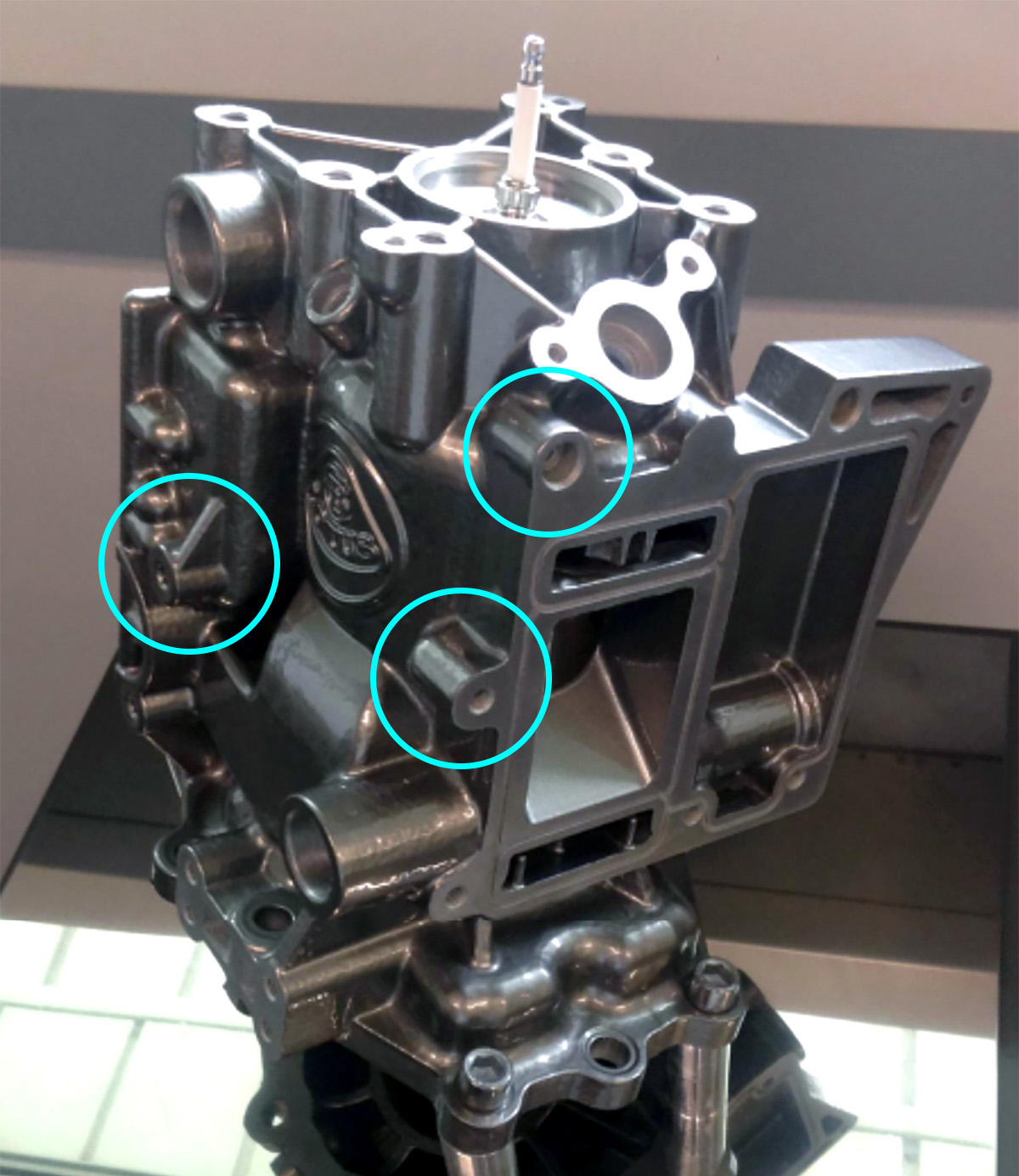

Now would be a great time to show you a picture of the actual cylinder head, but, as my confidentiality clause is still both valid and terrifying, I’ll show you a picture of something else to give you some context. This chunk of metal is the monoblock (a combined cylinder head and block) of Lotus’ Omnivore research engine from 2009, which is a single-cylinder two-stroke engine and therefore relatively simple; and it’s covered in bolt bosses. [Ed note: I circled three of ’em – Pete]

My new cylinder head and comedy-bolt bosses went through the design review without a murmur and passed testing with no problems, at which point my job was done. It then went into production, made no great impression on the world and, several years later, went out of production with no internet-verifiable reputation for massive cylinder head failures. Phew.

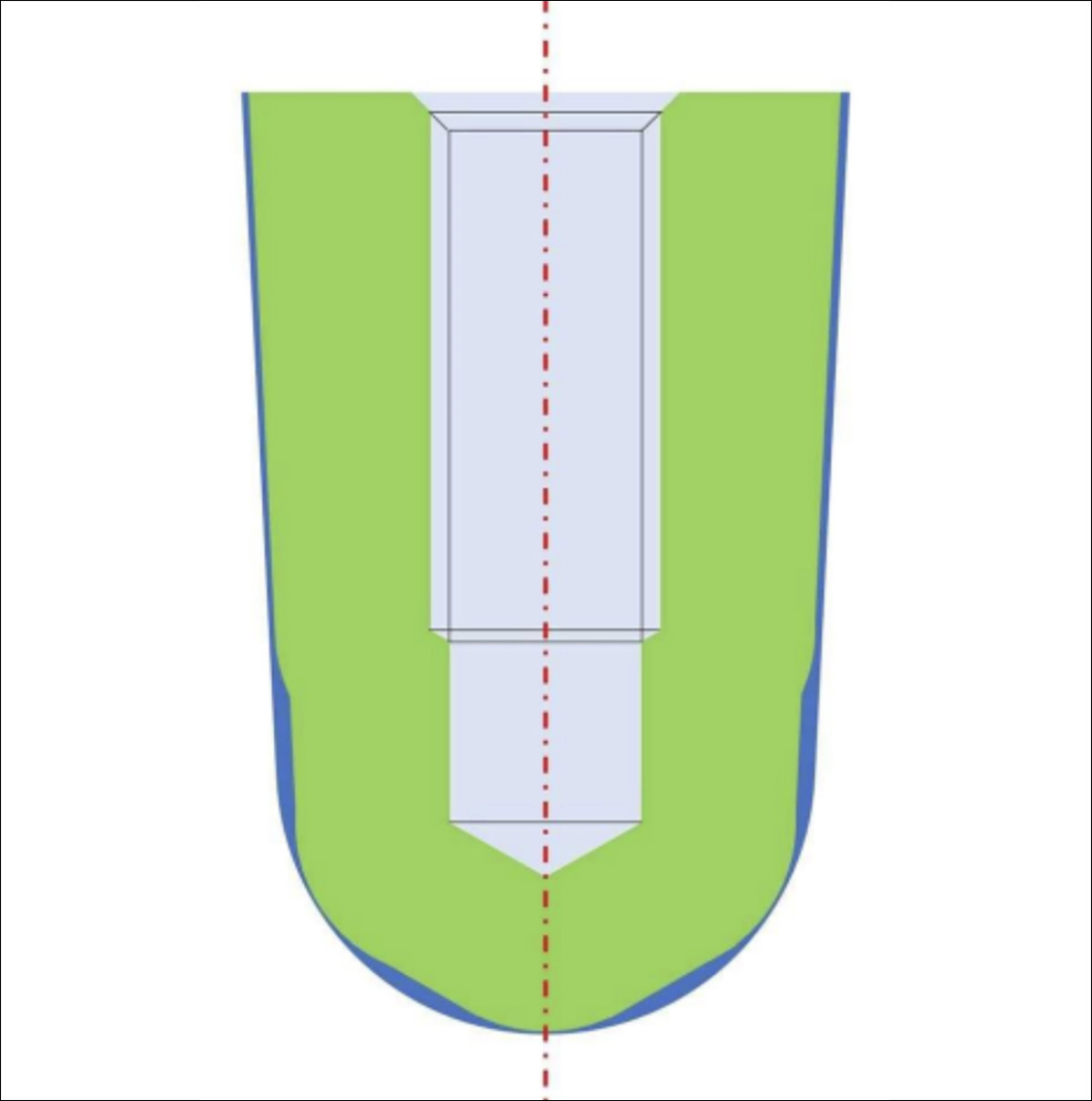

Years later, I was explaining this whole thing to a fresh, shiny, new engineer in the hope that they might strive to avoid lazy design, and they asked how much weight this actually saved. I had no idea, so I checked, but not before correcting them on the use of weight, which is variable, instead of mass, which is not. So I modeled up the standard blob and my slightly better version to compare the two…

It saved just 0.7 grams, which is 0.0015lb. But wait, you lose about half that saving because the bosses tend to be blended into a wall. So it saved just 0.35 grams, which is the approximate mass of the air in a small sigh of disappointment.

However, when you multiply that by the number of bosses per head, then multiply that by the number of heads made before someone else came in and redesigned it for the next version of the engine, you get a mass saving of 10,214kg, or 22,518lb. Over ten metric tons of aluminium that didn’t have to be mined, transported or smelted. I’m not going to do the maths on the environmental impact of that because it’s too hard, and I’m not going to cheat and get Google’s AI to guess a value, like I did earlier with the mass of the air in a small sigh of disappointment.

But if every car that engine went into did 100,000 miles before it died, then 1,021,400,000 kg-miles were saved (yes, I know that unit is a horrible mess of metric and imperial, welcome to the UK, where we sell fuel in litres but measure fuel consumption in gallons). If the average mass of my cars was about 1,200kg (which it is, I have a spreadsheet, obvs) and my average yearly mileage is 10,000 miles, then the kg miles saved is the equivalent of 85 years of me driving around (very roughly speaking). A few minutes of boredom has offset my personal transport needs for life, assuming I don’t keep driving until I’m 102 years old, which seems like a reasonable assumption.

I’m going to ignore the obviously egregious skewing of the figures that results from nine years daily driving an S1 Elise. And the three years in a 2CV. And whatever additional environmental harm the RX7 caused. Hope you don’t mind.

Top graphic images: Dave Larkman; DepositPhotos.com

1st welcome Dave.L!

I love engineering nerd articles written for the layman like this.

Add lightness thinking like this reminds me of a persistemt thought* about how much room exists to ‘addnlightness’ in already complex producta like an automobile!

*imagine all structural components and heavy components like engine blocks are designed like bird wings, i.e. a lattice of interwoven strands of material instead of a solid block. This should provide the opportunity to save emense amounts of mass on a per unit basis and therefore of course compounding significantly with scale.

This approach likely would require additive 3d printing playing a significant manufacturing role instead of being captive to design / prototyping as it has been.

This may (still) not be practical / profitable for a mass market targeted product. As is common, starting applying these techniques w/high purchase price automotive products makes sense, as this should afford opportunities to learn and make changes very quickly with less price sensitivity.

I appreciated the humor of saving the weight, and more appreciated the elegant flow of your thoughts.

Kudos

A great article, with equally enjoyable discussion (as per common around these parts) Welcome Dave Larkman and thanks staff for the choice/publication.

This is the most Lotusish article I have read all year. Or last year. Maybe this century.

Little bits add up! This is really neat.

Bolt, Screw, just call them what they actually are, springs.

Just as long as you don’t specify flat washers under your lock washers it is fine.

just call them what they actually are…

Certainly you mean ‘spiral ramps’ 😉

The real question is did this make service or repairs on the vehicle more difficult, because if you ask a mechanic that is the engineer’s primary job.

I do find it funny how that notion is thrown around so frequently when more book time equals more pay for a given job.

There is a prototype in the Lotus engine museum of an engine that is significantly lighter and cheaper because it was bonded together.

Somehow it never caught on, and mechanics should be grateful.

I don’t know, if something fails then it needs the engine replaced and engine replacements are gravy jobs, at least if you are good, especially once you’ve had a couple. Back in the day my favorite gravy was Caddy 4.1s especially the transverse flavor.

Fellow mechanical engineer here: I can tell we’re going to be best friends.

Both are wrong, they’re cap screws.

— Manufacturing controls engineer at an engine assembly plant

Dave: Slightly off-topic, but a question I have always wanted to ask a powertrain design engineer:

Why are we seeing so many poorly designed engines that require massive disassembly to replace a $25 part? example: Crank sensor of a Jeep 3.0 on the flexplate side requires transmission removal to replace. That sucks!.

Don’t design engineers ever think about servicing? Is design for serviceability even a thing?

I’m not a powertrain engineer, but I do engineer high volume industrial equipment with many similar constraints to automotive.

I can tell you most engineers really try to consider servicing, but we’re also trying to balance many competing priorities, many of which are out of our direct control, like overall project budget, timeline, packaging constraints, material limitations, etc. If it comes down to “this widget will be hard to work on or we kill the project”, you can figure out which one wins.

In one case, I designed a small fluid system with fittings designed to be accessed in a certain direction. I defined a “do not enter” envelope around that area so any engineer designing adjacent components wouldn’t put them too close to my service envelope. All was well for the first release, however, upon the next generation, a larger adjacent component was needed that intruded into my access space, and the decision was made (without me) to eat into the service clearance. Now those fittings are a nightmare to get to, and there isn’t anything I could have done about it.

I will say fewer and fewer engineers end up having to work on the systems they make. I worked for years servicing the equipment I designed, so you can bet I tried to make it as easy as possible to work on, but it’s a constant battle.

Young, inexperienced design engineers and the highest priority placed on cost reduction.

I’ve spent time laying on gravel using 3 12″ socket extensions and 2 universal joints getting the top two gearbox bolts off an MX5. Every three thousand miles (drifting is hard on clutches). I know about servicing, and I care about service access.

But the truth is cars aren’t assembled in the same way as they are serviced, and absolutely every engineered part is a compromise between several, if not dozens of often conflicting requirements. The fact that some items are hard to get to is because we fought for that access. It’d be so much easier and cheaper to bond-in sensors, or rivet on covers. However bad you think it is now it could be worse.

Plus, of course, some designer engineers aren’t as terrific as I am.

And I got made redundant. Imagine how good the engineers they kept must be.

Well, this was delightful. And it’s something everyone should remember. You might do things whose results are increments – and not big ones either – but when you zoom out and look at your cumulative effect you, yes you my friend, have made a noticeable difference.

This is the only automotive forum I actually care about. This is a room full of people who can enthuse about cars, not just the new ones but the old ones, the weird ones, the flying ones. We have taillight geeks and materials engineers. Literal car collectors, and collections whose descriptors start with the word, “Matchbox.”

This kind of thing is why I come here. For perspective. All of the perspectives. This is Autopia.