Like many of my generation, I watched the space shuttle Challenger explode on live television, while I was at school. I remember it very well, because I was a colossal space geek as a kid, and still am, as a kid well into his 50s. I was excited because it was unusual to watch a space launch in school in 1986 – the Space Shuttle program, while never coming close to reaching its predicted launch schedule of 50 or more flights per year, nevertheless proved capable of launching more frequent crewed space missions than ever before, with a peak just the year prior to the disaster of nine missions. Watching space shuttles climb that tower of flame and smoke into space had become almost routine. Maybe not “almost”; I think for most people a shuttle launch barely registered as news anymore. But this time there was a teacher aboard, so all of the schools paid attention.

The inclusion of that teacher was a huge deal; I remember the search that led to the selection of Christa McAuliffe, but more importantly I remember how it felt knowing that this was a real, normal person going up on that shuttle. She was just a teacher! I knew what teachers were like, I saw them get flustered and chain smoke in the teacher’s lounge and look exhausted and exasperated by me an all my fellow idiot kids – these were not superhumans, like I imagined astronauts to be, or at least DeLuxe-trim-level humans. They were people, and seeing a normal, bright but likely flawed person go on the shuttle really made it feel like things were changing, and soon space travel would be something we could all aspire to.

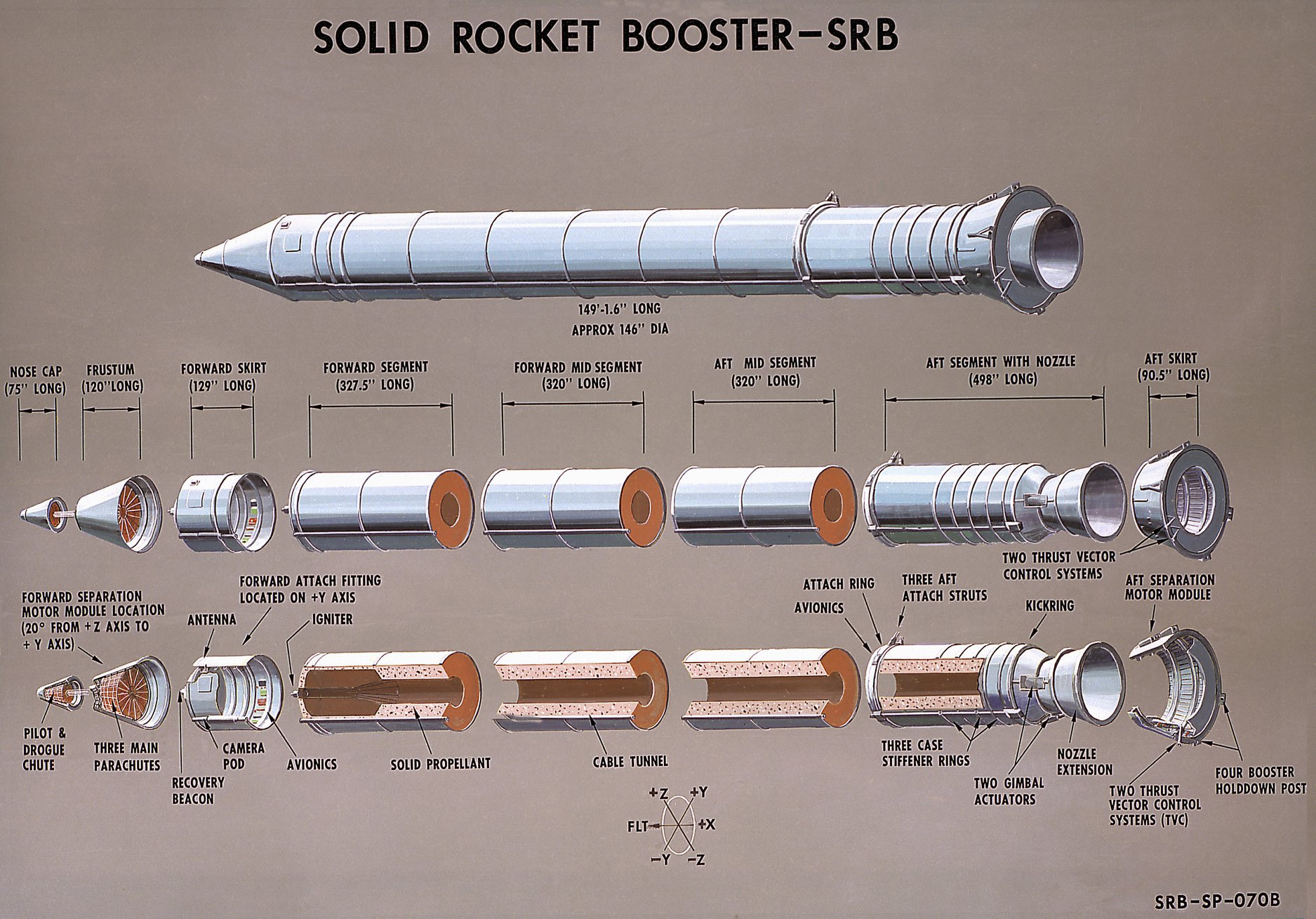

Of course, that’s not how it played out. I remember that I was in art class, which I loved, and I remember the big CRT television cart getting wheeled into the room so everyone could watch. I’d seen shuttle launches many times, and had memorized the diagrams and charts that were published in National Geographic, so I eagerly awaited each expected stage of the launch – the three main engines on the orbiter firing first, making their smokeless cones of barely-visible exhaust flame, then the massive bursts from the pair of solid rocket boosters mounted to each side, each one belching out huge columns of white clouds as they flung the whole shuttle stack into the sky, and then finally the two spent boosters ejecting, leaving the orbiter and its big orange fuel tank to continue ascending alone, until the cameras could no longer see it.

What I expected was not what I got, of course, and as soon as I saw that big ball of cloudy smoke and the two boosters careening around wildly and uncontrolled, I knew something was off. I remember that strange numb feeling for a few seconds while everyone was trying to figure out what the hell was going on, the announcers on the TV seeming confused, and most of my classmates pretty oblivious. That moment seemed like a very long time, but it wasn’t.

The realization of what happened soon came, both to the voices coming from the television and in our messy art room, with its big tables and stacks of pastels and paper and clay, student’s artwork of wildly varying quality lining shelves all around. There wasn’t a big uproar in the class, just a sort of sudden hush, like a huge tarp had been thrown over everyone as we all shared a moment of realization that, sometimes, no matter how well planned, no matter how smart the people in charge are, shit goes bad.

I think to appreciate the widespread impact of the Challenger disaster, you have to remember how much the whole thing was built up, and how hard a fall it was. The shuttle program was a huge success and a huge source of pride for America. These were the first actually re-usable spacecraft (though some in the program described them more as re-salvaged, due to all of the maintenance they required) and they were so much larger and more impressive than the dinky gumdrop capsules that came before.

We’d been launching them with seeming ease many times a year, and had gotten to the point where NASA felt confident enough to send up that teacher, to great publicity; the disaster couldn’t have happened at better moment, if the goal was to remind humanity about the concept of hubris. I feel like for those of us that saw it, there was one big common takeaway, even beyond the expected feelings of loss and tragedy about those seven people whose lives were ended that day. To some degree, they knew there were risks, and they willingly took those risks to do something they genuinely loved and believed in. That doesn’t make what happened less tragic, but it makes it a little easier to understand.

No, I think the more unexpected lesson that we learned then is that, to some degree, we’re all winging it. The people we trust in positions of authorities are still people, flawed people, and they make mistakes and are as susceptible to being influenced by the wrong things as any of us. I think there’s some seeds of the strains of mistrust of authority and expertise that many of us feel today, rationally or otherwise. And I also think once the initial shock and sadness filtered away, we were left with a good bit of cynicism. I remember that just a few days after the tragedy, gallows humor jokes about it were already spreading around the lunchroom. I’m pretty sure it was later that week when I first heard a kid ask “Why does NASA only serve Sprite on the space shuttle? Because they can’t get 7-Up!”

I mean, it’s a well-crafted joke, and gallows humor is always a part of dealing with a tragedy, but there is darkness beneath it, and I think we’re still dealing with some of those repercussions.

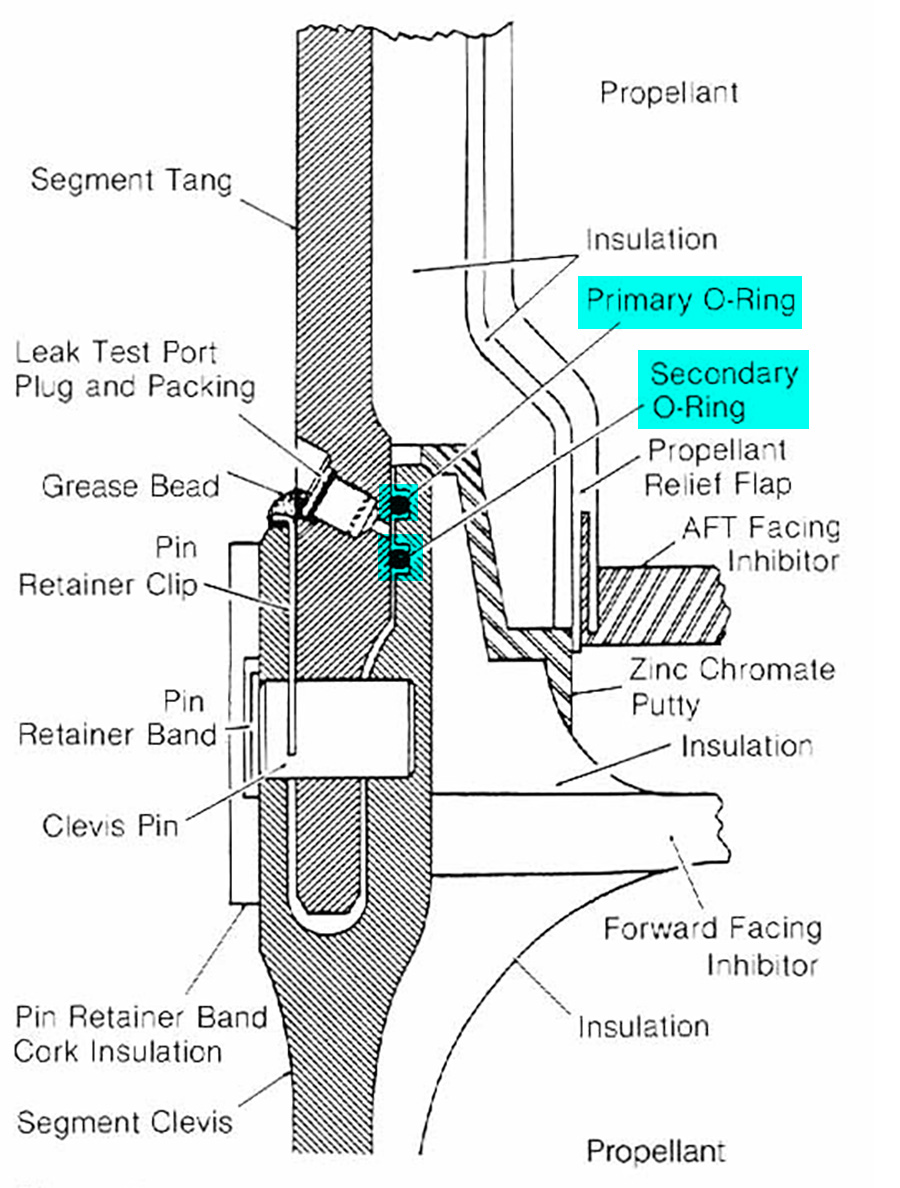

The reason the disaster happened was because of what seems like a small detail in the construction of the solid rocket boosters (SRB). The boosters were pretty remarkable machines – the largest solid rockets ever built, designed to be reused, and were constructed in several segments. The interfaces between those segments were more complex than you may realize, and relied on some rubber O-rings (can there be any type of ring other than an “O?”) to keep things sealed even while things were expanding and contracting based on thermal loads.

NASA and Morton Thiokol (who built the SRBs) were aware that these rings that sealed the joints in the SRB segments could have issues properly sealing due to loss of elasticity at low temperatures since the 1970s, but the issues were never thought to be particularly severe. NASA had observed these joint seals venting soot on other missions without further incident, and took this as proof that the issue was one that could be tolerated, instead of a symptom of something larger.

On the day of the launch, ambient temperatures were as low as 18 °F; the previously coldest shuttle launch had temperatures above 50°, and Morton Thiokol engineers actually expressed concerns to NASA about the elasticity of the O-rings at those temperatures before the launch, and were only confident in launching in temperatures 51° or higher; NASA managers didn’t accept these concerns as valid, and questioned if they expected the launch to be delayed until April.

The inability of these rubber O-rings to seal the segments caused plumes of hot gases to escape, which melted through the external fuel tank, causing it to break apart, and, from there, the entire assembly to be destroyed, crewed orbiter and all.

Famous physicist Richard Feynman demonstrated what happened to these O-rings very dramatically during one of the hearings about the disaster. He arranged to get a sample O-ring and place it in a clamp, then placed that into a glass of ice water, bringing the O-ring down to 32° F. He was then able to show, right there, that the frozen O-ring lost most of its elasticity and ability to return to its original shape at those low temperatures:

I think most of us know all of this by now; it’s been 40 years, after all. But I think it’s worth remembering, to honor the brave explorers who happily climbed into that delta-winged flying brick strapped to a massive column of fuel and two colossal firecrackers with only the goals of learning more about our universe, and how we can figure out how to explore it further, but also to remember that sometimes even the smartest people, the ones who actually make amazing things happen, make mistakes.

Sometimes huge mistakes. But that doesn’t diminish what they accomplish; if anything, it makes every success more impressive. The Challenger Disaster was a tragedy, but I do think we learned something. Some very specific things about solid rocket boosters of course – evolved versions of these same boosters are used on the new Space Launch System (SLS) rocket that will be sending people around the moon in a few months – but also something about, I don’t know, confidence? Over confidence?

Everything is so complicated. A bit of cold weather is what caused the failure of one of the most complex and carefully-engineered machines in all of human history. Everything is connected, every little thing affects every other little thing and on and on in a cascade of cause and effect that makes you dizzy. And yet somehow, we manage to pull things off, anyway.

We grope, we take risks, we fail, we try again. Seeing this disaster happen was sobering and shattered some illusions, but maybe those illusions were ones that should be shattered. Maybe we should have hope in things and people and ability, but not a blind hope. Maybe knowing that things can go wrong, horribly wrong, is a reality we should all keep in the back of our minds, and find a way to know it’s there and keep going anyway.

I’m not entirely sure of how the Challenger Disaster affected me or the so many others who saw it, but I know it did, somehow. I just hope I figure out how to turn it into something that honors those who died, and makes us better or smarter or something. At least not worse.

I was at recess when it happened, and when we got back in, heard about it as rumors before anything else. It felt like the jokes started almost immediately (“You feed the cat, I’ll feed the fish”).

And put the way Jason does, I wonder how much of a load bearing effect it had on forming Gen X cynicism.

My grandfather was a lifelong aviation writer, speaker, and lobbyist across his post-law, post-WWII career.

Every time there was a shuttle launch, NASA would put together some mementos like flight patches, roster, a few photos, and mount it all inside of a framed shadowbox that would be gifted to various aerospace/aeronautics illuminati. Since it was right around his retirement, they decided to send him one — and it coincidentally was the Challenger one (prior to the accident). Sad, but amazing, souvenir.

I wasnt around for Challenger, but i remember watching Columbia break up on the news before school that day.

I did recently listen to the Challenger book that came out a few years ago.

Was a fantastic investigation into it. Saw another comment that mentioned Allan McDonald, but Roger Boisjoly deserves just as much attention and memory.

He and I share an alma mater and major at, yet i never recall anyone mentioning him, even in our ethics courses for engineers.

Those assholes killed an entire shuttle crew because they didn’t want to wait until it was warm enough to launch safely.

Wow, so many youngsters. I didn’t see it live, but once it hit the radio (like Spotify with no choices) we wheeled a TV into the machine shop. I know the boomer question is always “do you remember where you were when you heard about Kennedy?”

I’m Gen Jones; I remember exactly where I was when I heard this, hearing Stevie Ray Vaughn dying (same radio, same machine shop), the first plane hitting the WTC (Motorola cafeteria Ed Bluestein), when Columbia crashed (Motorola cafeteria Oak Hill)

I can clearly remember watching it happen on TV. I was 14 years old and home because I was sick.My grandmother and I were watching it live and when the explosion happened my grandmother started praying out loud for everyone on board.I was sort of confused but felt terrible.It was sad as all the children,parents,and friends of the astronauts at the launch in the bleachers just kept looking up at the sky trying to figure out the tragedy they had just witnessed. I can still see the teachers mother and father slowly walking away as everyone was escorted off the site.

I was in 8th grade at the time. Strangely we were not in school that day. Either a teacher work day or maybe there was a 1/4 inch of snow on the ground in my suburb neighborhood outside Atlanta that kept us out of school.

I was being lazy as an almost 14 year old and watching the launch from bed. I actually could not reconcile what I was seeing in my brain. It wasn’t just a big explosion like you see in the movies, all slow-mo and seeing the thing break up inside the fireball. One second the shuttle was blazing a straight line (well sort of parabolic, but you know) into space and the next second it was just gone and a big cloud of debris and smoke where it was. I could see the boosters going and spinning all about and just didn’t quite get where the shuttle was. I guess I expected to at least see parts of it jetting along the path, not truly understanding the sheer amount of force the fuel exerts in an explosion like that.

About ten minutes after it my good buddy called me and we tried talking through what went wrong. But even though we were both into science quite a lot, we were also both art students much like Torch, and therefore both of us math-challenged.

So my experience was a bit different as I processed it alone. I’m not sure if that makes it better or worse but certainly different. It was truly a defining moment for most of a generation and one of those times where you’re just so shocked that every detail of the event, what you’re thinking and how you perceive what is going on around you is stuck in your mind’s eye with more clarity than other memories. Truly surreal.

I remember living it twice, once in class and once again when Webster did a show about it.

I was in line at the cafeteria getting a fried burrito and grape soda, just like I did at lunch every schoolday in 9th grade.

I heard someone say the shuttle blew up. I remember thinking “There’s no way. There was probably some minor malfunction, and the telephone game has turned it into the whole thing blew up.”

It wasn’t until I got home that I found out how wrong I was.

Ironically, when 9/11 happened, I was at work and heard the initial reports on the radio. Again, I immediately assumed the reports were exaggerated. Like, a small plane had hit a building or something. Maybe I’m too optimistic about the possibility of bad things happening.

Also, never forget it was almost Big Bird on that shuttle instead of Christa McAuliffe.

Our dark joke? Did you know the astronauts all had blue eyes? One blew that way, the other blew thattaway.

My wife and I watched the whole thing live. The TV stayed on for the next 3 days. I’ve never been able to hear “go with throttle up” without wincing since.

I have a very good friend of 50 years now. She was part of the people who did the computer launch simulations trying to determine what acceptable real life launch parameters would be. She has told me repeatedly that almost everyone at NASA wanted the launch scrubbed that terrible morning.

But there were other forces at work, including Ronald Reagan. Who BTW was very interested in pissing off all the Commies worldwide by showcasing US superiority in space.

My friend left the shuttle program after Challenger. But she just retired from NASA a couple years ago after 44 years.

I could not help but think of Reagan’s comments about the loss of the astronauts and how it seemed comforting.

And how those remarks would have sounded if the Orange guy had been president.

“It’s a sad thing. They were good people, even if one or two were of immigrant descent. I’ve been told a couple may have been liberal Democrat scum, but we won’t talk about that now. Except for the liberal scum that’s trying to destroy our country right now. It’s time we eliminated all the people at NASA from foreign countries, they are spies, and they are ripping us off, just like those penguins who won’t pay their fair share to NATO. But that’s all gonna stop soon. Now somebody play YMCA so I can get off the stage before I shit my pants.”

I don’t even remember what was happening in Kindergarten that day but, I keep two posters on the wall at work. One is STS-51-L/Challenger at liftoff to remind me that the perfect start can go terribly wrong when management doesn’t listen to/inappropriately pressures the engineering team. That one also has the Kranz Dictum overlaid with the mission patches from Apollo 1, STS-51-L/Challenger, and STS-107/Columbia. The second is the more positive outlook with the open parachute of the Mars Perseverance where they embedded the JPL motto Dare Mighty Things in code.

Both remind me of the tension of engineering management. Learn from and don’t forget the past, but don’t let it stop you from pushing further.

“Not one of us stood up and said, ‘Dammit, stop!'” – Gene Kranz, NASA, 1967

“Take off your engineering hat and put on your management hat” – Jerald Mason, Morton Thiokol, January 25, 1986

“One of my regrets is that I didn’t break the door down. Like, why not just go and go to the very top and be very demanding and insisting on what we need?” – Rodney Rocha, NASA, 2008 on Columbia’s foam damage

While today marks the 40th anniversary of the loss of Challenger and her crew, yesterday marked the 40th anniversary of the management failure that led to the loss. Engineers warned of the O-Ring failure. Management (both NASA and Morton Thiokol) pressured the engineering teams and overrode those warnings. The lessons of Apollo 1 were forgotten 19 years later. The lessons of Challenger were forgotten 17 years later.

Failures happen all the time. Most are forgivable.

Failures of redundancies, on the other hand, are absolutely unforgivable. It’s one thing to make a mistake. It’s an entirely different thing for that mistake to go unnoticed by several layers of people whose job it is to notice such mistakes and correct them.

Most tragic failures in history, especially mechanical ones, are not tragic because of the failure. They become tragic because of the failures that take place after the initial failure.

I was in fifth grade. My memories are a bit faded, but what I can recall is the amount of sheer fun and energy made its way into the classroom leading up to this flight. It seemed like everyone had a friend of a friend who knew a teacher that was in the running to be on that shuttle.

Every other teacher (my mother included), turned the creativity up to 11 as activities and lessons led up to the flight. I remember my teacher set up an empty cardboard box decorated like a TV set at the front of the room and each of us took a turn playing like we were TV newscasters presenting news reporter about the upcoming shuttle launch. Mine was about the diary Christa McAuliffe planned to keep while she was in space.

Memories are weird, and I can see the equivalent of a still photo in my brain of the classroom I was seated in when it happened. Lots shock and disbelief bounced across the room in ways that I honestly couldn’t process at the time. Back then the shuttle program was cool in a mainstream kind of way. We all knew the names of each shuttles, and frankly the Challenger was my favorite just because I thought the name was cool.

I’m not sure why I’m typing this, other than to share some camaraderie with fellow Autopians – this is one of those historic, generational “where were you” events that have stuck with us forever.

Thanks for this tribute, Jason – I think you really captured the moment and reminded us of the comfort we can draw from the sacrifice these brave astronauts gave us that day in the name of science and learning.

I was in 5th grade, and like everyone in the US, Canada was watching too. We had the CanadaArm to be proud of after all. I don’t really remember the accident. I do remember my 5th grade teacher going “oh shit” and running to the front of the class to turn the TV off. I think that’s was really cemented that something was wrong, because before then the class was just confused for a moment. After that, there was crying.

I was too young to remember this happening, but, I do recall in 1st grade or 2nd grade, our social studies textbooks were several years out of date, and the section on the space shuttle program basically ended with Christa McAuliffe being selected to become the first teacher in space, with the potential for students like us to attend classes given from orbit, and nothing further than that. The teacher obviously had to fill in the blanks

I was 3rd grade, and watched it in the cafeteria with the rest of the school. I remember it and the walk back to class being fully confused. They just kind of turned off the TVs and asked us to go back to class quietly. It was horrible.