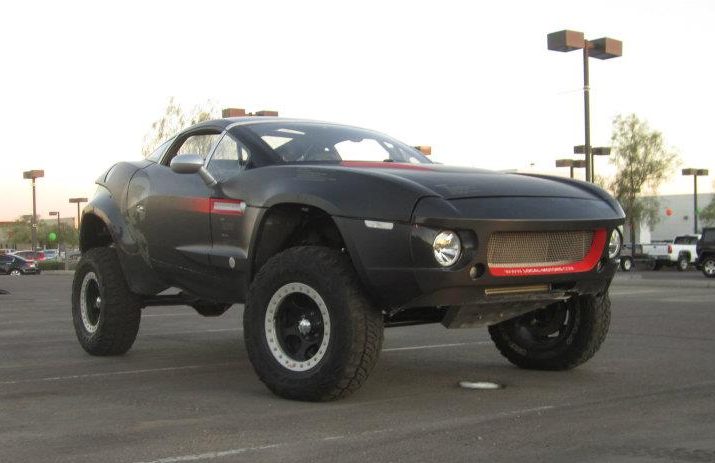

If you spent any time as a car enthusiast throughout the 2010s, you’ve likely heard of a brand called Local Motors. The startup carmaker, based in Arizona for most of its existence, was best known for the Rally Fighter, a road-going two-door coupe with huge tires, a long-travel suspension, and a GM-sourced LS3 V8. Built for off-roading and desert running, it embraced the “off-road sports car” trend long before Porsche or Lamborghini considered building off-road versions of its performance cars.

Like many startup automakers of the 21st century, Local Motors didn’t have a happy ending. It shut down shortly after pivoting to building autonomous buses back in 2022. But the story of how it lasted for 15 years, and how one man ended up with all of the Rally Fighter spare parts in a container in the desert, is endlessly fascinating.

That man, Nick Bauer, was a long-time Local Motors engineer, having laid hands on every Rally Fighter produced. In a phone conversation with me, he laid out the inner workings of the company, why he left, and how he ended up with the original BMW diesel-powered Rally Fighter prototype.

Let’s Start At The Beginning

Local Motors was co-founded in 2007 by John B. Rogers Jr. with the goal of becoming a low-volume manufacturer, kicking off its operations in Wareham, a Massachusetts town one hour south of Boston. The company differentiated itself from others in the sector by claiming to be quicker and more efficient, using crowdsourcing and off-the-shelf parts to get products to the market in a condensed timeline. It also made a big deal about wanting to work with its customers to tweak products, a method called “co-creation.”

Here’s a good excerpt from a Wired story covering the brand back in 2010, just before the launch of the Rally Fighter:

The company says it can take a new vehicle from sketch to market in 18 months, about the time it takes Detroit to change the specs on some door trim. Each design is released under a share-friendly Creative Commons license, and customers are encouraged to enhance the designs and produce their own components that they can sell to their peers.

To show off its manufacturing prowess, Local Motors decided to launch the Rally Fighter, solidifying Local Motors in the automotive zeitgeist.

The Rally Fighter’s Early Days

The original Rally Fighter prototype was built in Massachusetts with help from Factory Five Racing, a kit car company just down the road from Local Motors, known best for building Shelby Cobra and Daytona replicas.

“That Chassis was built in-house by this guy who previously made cranberry picking machines,” Bauer told me.” A lot of these guys who founded the original company all worked for the same company called Factory Five Racing. I think that’s how a lot of the body molds got started. It’s rumored—I don’t know the exact details—that Factory Five was an early investor in the company.”

The Rally Fighter’s design was a result of a design competition held by Local Motors in 2008, and won by Sangho Kim, who was then a student at the ArtCenter College of Design in California. Shortly after the prototype was built, the company moved to Arizona. Bauer believes the move was due to several reasons.

“They moved to the desert to build it, so it’d be in its natural habitat,” he told me. “Although I think that one of the reasons why they did it is for the lax kit car laws.”

Here’s Where Bauer Gets Involved

After almost a decade of interacting with people in the startup business, I’ve found that getting involved is mostly down to luck and knowing the right people. And it seems like that’s how Bauer got in.

“I heard about Local Motors on the trail,” he says. “I was into off-roading at the time. I was wheeling with this guy named Scott Brady, who has this website, Expedition Portal, and he was talking about this startup company that moved to Phoenix.”

Brady suggested to Bauer, who was a freshman engineering student at Arizona State University at the time, that he send in his application to apply to be an intern. Sadly, he didn’t get selected. But because he liked what the company was doing, he still made sure to have a presence there.

“They hired two seniors off the Baja team, but none of the freshmen. So I didn’t get that job,” says Bauer. But I was always messing around at the facility; it was a super cool startup. I couldn’t even drink at the time, and I went to one of their open houses. This chick came up and gave me a beer because they had SanTan Brewing for free in the facility. I’m like, ‘I’m 20. I can’t drink this.’ And she’s like, ‘Don’t worry about it.’ I totally didn’t drink it. That was the atmosphere of Local Motors at the time. It was nice. It was cool, man. It was a true startup. We had a whole room in the facility, a little tiny room, probably like 12 feet by 12 feet, full of free candy. And they had a beer fridge in there, and beef jerky, just all the good stuff from Costco, for free.”

Bauer suspected they might one day bring him on board, until he angered the engineering team by making a comment online criticizing their design.

“They were demonstrating the Rally Fighter at another open house, Bauer told me. “And they took it from a high ride height position to a low ride height position. And when it went down, it sounded like a pair of sneakers scrubbing the floor. I just saw the toe of the front suspension go out. I was like, ‘Ooh, major bump steer.’ I made a comment on Facebook. My friend, who got the job, says, ‘They’re never gonna hire you, they’re so pissed off at that. You insulted their engineering.’ I’m like, ‘Well, they just need to move this around and stuff and improve the geometry.’ It was bad, man. I ruined my shot.”

Still, Bauer’s closeness to those on the Local Motors team and some real-deal experience meant he wasn’t totally out of luck.

“A few months later, they were building three cars for production,” Bauer says. “It was a SEMA rush because it was the first three cars. And they didn’t have enough people, and they needed fiberglass work. I worked in a little race shop doing fiberglass and carbon work. So I went in there and helped them do some of the small fiberglass changes. I made a mold for them and stuff. I ended up getting a job, I never left.”

Bauer would go on to work for Local Motors as a full-time engineer from 2010 to 2016, providing an in-depth perspective into the company’s operations.

The Ups And Downs Of Startup Life

Bauer was employed for the entirety of Rally Fighter production, according to him. Wikipedia says Local Motors built 50 examples, but he believes that number is closer to 92 units. “It’s close to 100, but less than 100,” he says. That’s roughly 15 cars per year. Of course, as with any startup, things weren’t always smooth sailing at the company.

In one story told to me, Bauer recounts the day he nearly got laid off when, by chance, the company’s only running Rally Fighter at the time got crashed, unlocking a reason for him to stay.

“I think we hired a new sales guy, and he let his friend drive his car,” Bauer says. “And I think this was when the economy was doing really bad, because the company was really struggling. We weren’t selling much. I guess they just swapped seats, he got in it, and the car swerved, and it ended up on its side. It flopped at high speed.”

Earlier that day, Bauer had been informed that he was being laid off. But he was still hanging around at the factory when the news of the crash came in.

“We get the call. I was depressed, but I was still hanging at the factory. I’m good at off-roading, so they said, ‘Nick, come with us for the recovery.’ So we took the shop truck out. It was an extended cab Chevy Silverado Duramax with like six guys in it. It was pretty packed. And the CEO of Local Motors was up front. He was stoked.”

Bauer says Rogers was excited because he wanted to see how the body held up in a wreck. Meanwhile, the rest of the crew was sad because 1. The company’s only running car was wrecked, and 2. Because Bauer had just been laid off.

“So we go out there and it’s actually held up really good,” he told me. ”The internal structure is good. The body was messed up, and there was a cop there, a sheriff, and he got his winch and put it back on its tires. We were expecting a ticket, but he’s like, ‘Looks like this guy’s in trouble good enough.'”

“There was this body out in our display area where the public could come in and look at stuff that we had wrapped with the special patterns,” Bauer continued. “This body was dropped by UPS. It was cracked in the corners and stuff, so it was one [set of body panels] we wrote off. We didn’t have any bodies in stock at the time, so on the way back, I said to the CEO, as a joke, ‘Hey, if you keep me on, I’ll put that body on that car. I’ll fix it up and do it.’ And my payroll kept coming in, and I kept coming in, and ended up putting that body on the car.”

A Behind-The-Scenes Movie-Maker

Movie buffs will know the Rally Fighter made appearances in two blockbuster films: Transformers: Age of Extinction in 2014 and The Fate of the Furious in 2017. In a video published right after the Transformers movie came out, Local Motors’ then tactical engineer Buddy Crisp detailed an on-set incident that led to some damage to one of the stunt cars:

If you don’t feel like watching the video above, basically, there was a scene in a cornfield where a Chevy Sonic was being chased by two Rally Fighters. “I guess the guy in the helicopter screwed up, called the shot wrong, and the rally fighter T-boned the Chevy Sonic,” Bauer told me.

Amazingly, there wasn’t much damage to the Sonic. It was basically a Mitsubishi Lancer Evolution drivetrain underneath, with a Sonic body grafted to the top and a tubular chassis, according to Bauer. So it took the hit and sustained only cosmetic damage. The Rally Fighter wasn’t so lucky. Bauer was sent out by the company to make repairs to the frame, where he became a quasi-shop manager for a group of movie mechanics.

“I had like two days to fix it,” Bauer added. “It was stressful. They had a good team. We were working in this abandoned Home Depot. It was in the middle of Texas—I want to say Austin. And when it would rain, there the rain would come in through the skylights that were all busted and hit the ground, and instantly evaporate the steam. It was so hot.”

That’s life at a startup. One day, you could face a layoff due to no one buying your cars, the next, you could be shipped off to Texas to prepare a car for a Michael Bay movie.

The Move To 3D Printing

While Local Motors is best known for the Rally Fighter, it did a whole lot more in the automotive space. It built a prototype called XC2V for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) in 2011, and also worked with the U.S. Army to develop better ways to solve issues by working with the soldiers who actually use the products.

Local Motors was also the designer for the Domino’s DXP, a delivery hatchback based on the Chevy Spark that could carry up to 45 pizzas at a time, with a special warming compartment in the rear seating area where you could keep up to 10 pizzas warm while the car drove to the delivery location. My colleague Jason Torchinsky did a whole deep dive on the car, which is very much worth a read.

Local Motors was among the first companies in the automotive sector to lean into 3D printing for manufacturing purposes. Its proof-of-concept vehicle, the Strati, was shown in 2014. It used a fully 3D-printed monocoque and the electric drivetrain from the Renault Twizy, of all things. According to Bauer, Nissan wanted to work with Local Motors, so the two companies imported a Twizy, a funky two-seater designed for European roads and only sold overseas. He says getting the drivetrain to work on the Strati was tough.

“This is a car from another country, no documentation, [I had] nothing other than the car,” says Bauer. “I just started cutting apart the harness and seeing what would work. I had to build a huge backbone out of welding cable, because the Strati is the all 3D printed materials, so you have to have a ground. I just had to ground every component individually.

“And it worked, man. I drove it around. I was doing all that at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, working in this transportation lab, just working my butt off, inhaling all this 3D-printed stuff, taking a saw all to the car so I could put the freaking steering rack in, and cutting apart the harness. [Those] two weeks, man, I was freaking out. It almost killed me.”

So Much For Crowdsourced Cars

Production of the Rally Fighter ended in 2016, and shortly after, Local Motors pivoted to the autonomous bus business.

“They started getting into autonomous vehicles, but I wanted nothing to do with that,” Bauer said. “One day, this thing called an Olli showed up. It just showed up. We were like, ‘What the heck?’ Because it went around engineering’s back. We had no clue [it existed], we didn’t design it. I wanted to be nothing part of that because I can’t put my name on something like that. The company was just changing, and it was scary. It sucked.”

The Olli, Local Motors’ first and only autonomous vehicle, brought new funding to the brand and eventually saw limited success in places like Turin, Italy, where it was used to shuttle people within a United Nations campus.

“I love the company,” Bauer says, “Local Motors is an awesome place. It just turned into, I feel, the exact opposite of what they were trying to do initially. Instead of having the community vote on vehicles, it became what I feel marketing wanted to make. We no longer had transparency, and we ended up making some very poor quality vehicles that I thought didn’t represent the brand well.”

Bauer might’ve had a point. 3D printing and the autonomous bus business weren’t enough to keep the company afloat. A 2021 Olli crash in Toronto that left the vehicle’s safety operator “critically injured” probably didn’t help the brand’s reputation, either. On January 14, 2022, Local Motors shut its doors for good.

How It All Came Together For Bauer

Unlike the Rally Fighter production cars, which used a naturally aspirated LS3 V8 supplied by GM, the original prototype used a turbocharged diesel straight-six from BMW, the M57.

“The prototype pre-production beta car—we call it Beta—was well loved by the company when I got there. It was worshipped like a god,” Bauer says. “I always loved it. But as we started making production cars, that car got ignored. They put it outside. I always felt bad for it, so I always made sure it had good tires on it. I always made sure it was registered, and I always drove [it] around. I loved driving that car around.

“But it would break all the time, because it turns out [the engine from a] 335d doesn’t like being shoved into something else,” Bauer added. “I think they paid an outside firm to do it. So the knowledge of how to repair that car and how it went together was lost. I just ended up picking it up because I loved it and just always fixing things on it. Keeping it going.”

After Bauer left Local Motors, he was informed by a colleague that the company was going through some tough financial times and planned to sell off a bunch of its assets, including Beta. Having such a deep connection to the car, he decided to make it his life goal to buy it. At first, the Local Motors people weren’t taking him seriously about buying the car, so he took drastic measures.

“I got a gallon-sized Ziploc bag and I filled it full $100 bills as much as I could,” he says. “I pulled out everything I owned, put it in cash, put it in a Ziploc bag, and walked around the factory with it. The guy who was liquidating the inventory, that got his attention. He’s like, ‘I can’t take the $100 bills. You’re going to have to wire us the money.’ So we started negotiating, and it went to a silent auction.”

Bauer won the auction and left that day with the original Local Motors prototype, which he still owns today. But that wasn’t all he got from that faithful liquidation period in 2020.

“When I was there, there was another separate bid for this semi truck-sized pile of rally fighter parts,” he says. “It looked like a lot of junk. A lot of people took shocks out and stuff, so there was a lot of junk. The guy’s like, ‘Just make me an offer,’ and I made an offer. He’s like, ‘That’s too low, double it.’ I got it for a good deal, but it was funny. When I was picking up stuff [the next day], a bunch of the stuff was missing when I went to pick it up. Employees were picking out of the pile, and I see this stuff come up for sale on [Facebook] Marketplace every once in a while. I’m like, ‘God damn it.'”

That “pile of junk” ended up being virtually every spare part for the Rally Fighter remaining in Local Motors’ inventory. Bauer’s become the go-to for owners who need replacement parts that aren’t easy to fabricate themselves.

“I have a lot of Rally Fighter inventory,” he says. “It’s awesome, a lot of the parts are special. You can’t recreate some of some of them easily. I sell parts to the other Rally Fighter owners every once in a while. Someone needs something, they call me.”

Bauer also retained some original design files for parts.

If I don’t have it, I can get them the file so they can make it, or direct them to a point where someone else could make it” he added.

@startupslick Replying to @fritzz61 #automotive #rallyfighter ♬ original sound – StartupSlick

Bauer estimates he’s kept around 10 Rally Fighters on the road using parts from his supply, which he keeps in a storage container in the Arizona desert. Remember, much of this car was built using off-the-shelf parts, meaning maintenance is actually pretty straightforward. The only thing he’s worried about with regard to parts is the glass.

“Everything’s easy except the glass,” Bauer told me. “Everyone’s freaking about the glass. There [are] basically, like, no pieces left. So I think what’s gonna have to happen is, we’re going to have to get together as owners and invest in the tooling and get them made somewhere. It’s not cheap. Automotive glass is hard.”

The Rally Fighter is an important piece of automotive history. Even though the company is dead and gone, the cars will continue to exist, thanks in part to Bauer. And that warms my heart.

Top photo: Nick Bauer

Bauer Motors has a great ring to it… Wonder if he still has any connections at Factory Five?

There were a couple of auctions when Local Motors shut down but all the cars got pulled at the last minute.

https://svdisposition.hibid.com/catalog/349158/local-motors–2

I saw a Rally Fighter driving down Seventh Avenue in NYC once, and thought I’d see a lot more of them. Never did, sadly.