I actually wrote about this over a decade ago, but I found myself thinking about this once again, the fact that, in 1972, the first real-world object was “scanned” and translated into three-dimensional data to become the very first actual, physical world object to be turned into a computer 3D model. That real world object was a 1967 Volkswagen Beetle owned by the Marsha Sutherland, the wife of Ivan Sutherland, the computer graphics pioneer.

What makes this all really great is how that Beetle was scanned. Remember, this was in 1972, and literally nothing had ever been 3D scanned before. Professor Sutherland was teaching a graduate-level computer graphics class at the University of Utah, and issued a challenge to his students to find an object to attempt to render in a realistic manner on a computer. It had to be something very recognizable, something iconic, and something large enough that could be worked on as a group.

A Volkswagen Beetle was a perfect choice.

Remember, this was 1972: one year after the very first microprocessor was released, the Intel 4004, and the year that Atari’s Pong hit the arcades. That was the level of mainstream computer graphics at the time: moving squares on a screen.

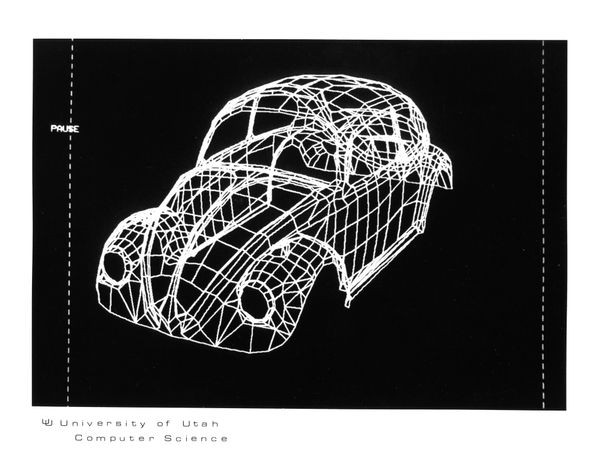

But Sutherland and his students could see beyond Pong. They were working on real three dimensional objects that could be stored as data in a computer, then moved and rotated just like an actual object, and rendered, with light and shading. But to do this, they needed data. There were no 3D modeling programs, no scanning devices – but there was a class of students with yardsticks and yellow marking crayons.

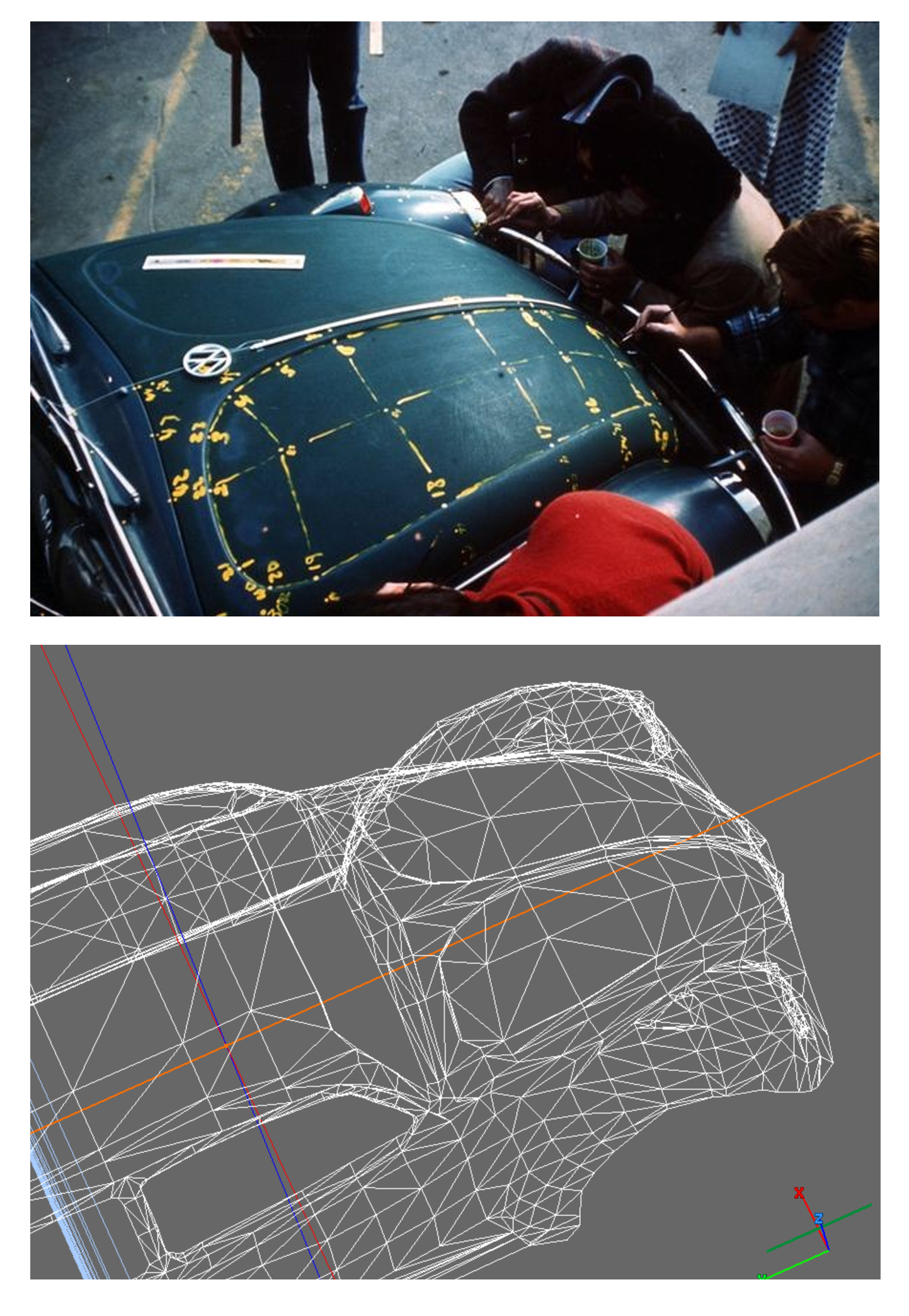

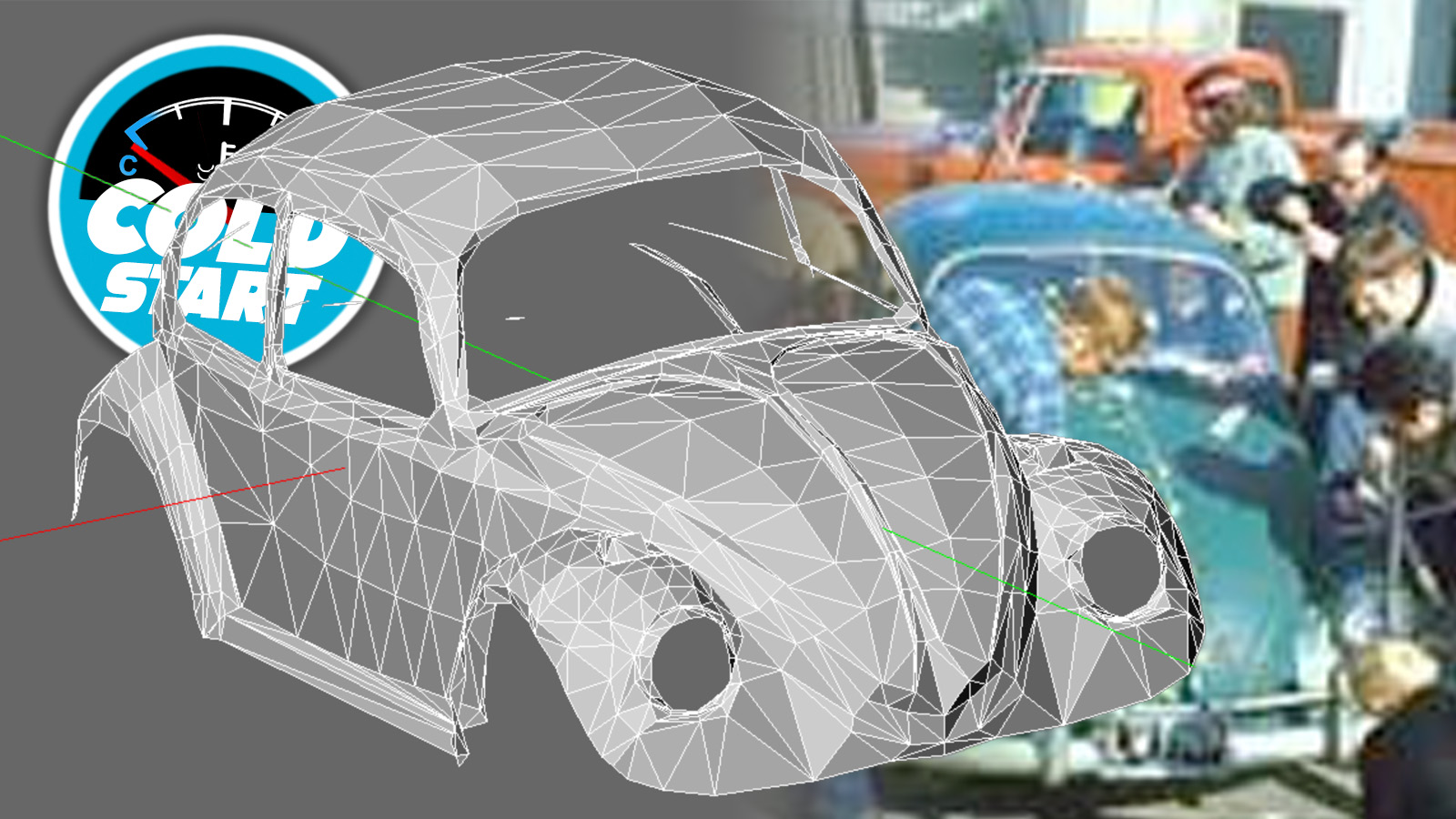

As you can see in the image above, the Beetle was scanned by measuring points and vectors drawn on its surface, all by hand, and that coordinate data was entered into a text file.

This was a group project, groups of students assigned to different sections of the car, taller students taking the roof, shorter ones getting the hood, fenders, and other lower body parts.

Here’s what one of the students, Robert McDermott, remembers of the process:

We used yardsticks to measure the x, y, and z coordinates of the painted points on the car surface. The Beetle was assumed to have left to right symmetry so we measured only half of the car. The process was slow and tedious, taking many class sessions to complete. Marsha was a wonderful sport as she drove the car around town festooned with our markings.

I love that Mrs.Sutherland drove the Beetle around covered in the lines and numbers, which I bet looked pretty cool.

The wheels weren’t measured, nor the bumpers or many other details, but it’s worth noting the turn indicators atop the fenders were measured, as were the chrome headlight bezels, which were new for ’67.

Once the car was measured into so many polygons, there was still a lot of work to do to make a coherent whole; the various sections didn’t line up perfectly – a yardstick used to measure metal with compound curves isn’t exactly the most precise methodology – and duplicating and mirroring the data to make the other side – longitudinal symmetry was assumed, so they only measured half the car – wasn’t easy either.

By the time all of the human effort going into measuring the car, refining the data, and the computer time was tabulated up, it was estimated that the cost of the project was likely worth more than the Beetle itself.

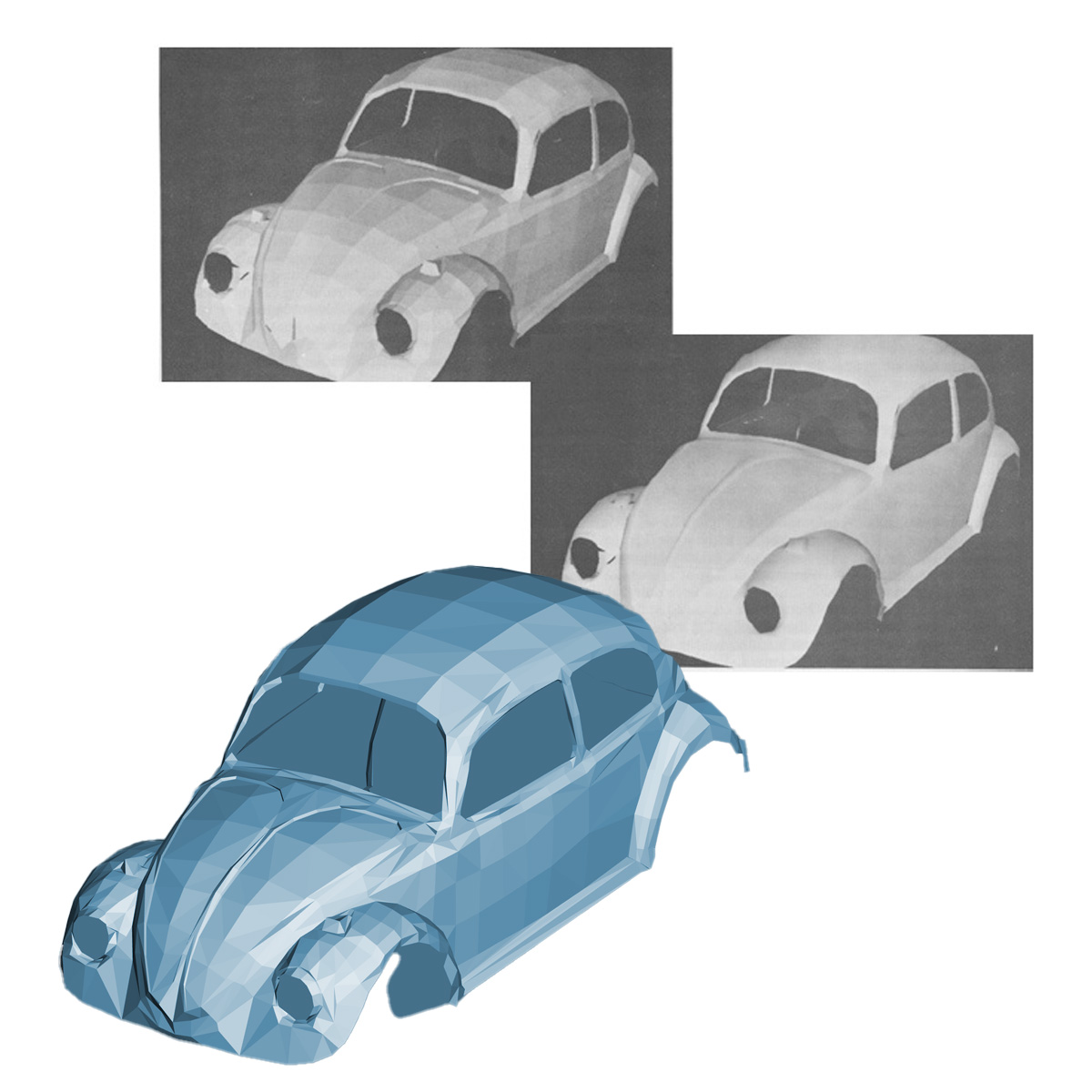

The final results weren’t displayed on a monitor, like we would today, as monitors capable of displaying shaded images simply didn’t exist. To render flat polygon-shaded or smoother Gouraud-shaded images (Henri Gouraud was a PhD student there as well), hardware was built to render images directly onto Polaroid film and later, 4×5 photo negatives.

You can see rendered examples above there, with a modern flat polygon rendered Beetle, using that original data file, from the Mac laptop I’m typing this on now.

When I wrote that first article about this years ago, I couldn’t find the exact original 3D data file that Sutherland and his students created, but I’m happy to say that’s no longer the case. Here is a link to that original 1972 hand-scanned 3D file. I love that this data still exists and is available; it is literally the direct result of those students hand-measuring lines on an actual Beetle, way back in 1972.

I don’t think it’s too much of an exaggeration to say this crude model is the start of all of the incredible 3D CGI used in so many things today, and it all started with a humble little Beetle.

It’s strange to think of a 3D file as a genuine historical artifact, but I think we can safely say this qualifies.

I raise my teapot to all the pioneers!

I worked briefly on the Real3D scanner project that Lockheed tried to bring to market in the early 2000’s. It was an exciting time. Now your phone could do all of what it did and more, but the technology had to start somewhere. Interestingly, the software was the hard part. It always is.

I met Ivan Sutherland years before that, when his company Evans and Sutherland were pioneering simulators. Mostly for military, but they were open to other applications. Military just happened to be the only ones with the money. Fun fact, they also developed their own graphics processor, which I was briefly involved with in bringing to market. If I recall, that IP is all with NVIDIA now after multiple acquisitions.

This is exactly the sort of reference I come here for!

Maybe it’s just me, but this sounds way more interesting than a 3d model tediously generated by inputting each vertex by hand. How on Earth did they convert 3d computer data to analog film?

Right? Like, what!? Torch buried the lede and then just glossed over it like that was just a thing we always did. It may not be car related but considering it was used on this beetle scan, it’s loosely related and sounds fascinating.

Great article ???? Gonna set the cat among the pigeons, Ray Holt working for Garret Air research beat Intel by two years. Look up F-14 Tomcat C.A.D.C air data computer.

Great stuff Torch! This is the kind of article I can leave up on the screen at work and it looks like I’m doing research of some sort.

Around 25 years after this was done, the layout for scanning cars looked rather similar, at least for the vehicles I got to digitize. Working for a start-up specializing in using 3D animation for litigation purposes, particularly accident re-creation, I was part of a team that would find exemplar cars and go digitize them.

We used a sonic-digitizer that utilized an array set to pick up signals sent by a probe. The process was fairly straightforward: use painter’s tape to mask out a grid over one half of the car, set up the array, get the software running (basically an AutoCAD extension) and start taking points – one at a time. We would always try to get the side where the gas door was located, as the data would be mirrored in the final model and that was something which was much easier to smooth over than it was to add in.

The process was incredibly tedious and would take about a day to get the data for half of the car. Once that was done we could take it back to the office, export the points and splines into ProE, and finally make surfaces to create an accurate model for use in a 3D animation.

As time went on, I ended up being the first one at our company to start exporting the data over to 3ds Max, which made surfacing and building the details much easier. ProE was a great tool, but building surfaces in there was slow and like everything in tech, faster, faster, faster was the mantra of the day.

This was close to the coolest thing in the world to an architecture student who had previously been in engineering, i.e. myself. And, it was a big part of why I dropped architecture as well in favor of Art and Design as way to fast-track out of school and start a career in 3d animation.

Nowadays everything’s done either with 3D models purchased from 3rd party vendors such as TurboSquid if the accuracy isn’t that important or exemplars are laser-scanned with a FARO machine if the accuracy is important. Additionally, there’s the option of taking a bunch of high-res photos and processing those through Reality Capture to produce a fairly accurate model, or at least the base to build one off of.

I’m still at it today amazingly enough. Thanks for the trip down memory lane – It’s wonderful to know it all got started with a vintage Beetle scan.

To be fair, a ‘67 Beetle wasn’t exactly vintage in 1972; to my mind it’s even crazier that they used Mrs. Sutherland’s daily driver. If she had got in a minor fender bender when they were halfway through the measurement process, they might have lost hundreds of hours of work and never finished the project!

The daily-driving part does make me flinch a bit thinking about it. Reminds me of early on when I decided to sit in a car we were actively digitizing and was informed not to do that post-haste as we’d have to re-digitize the verification triangle and add another layer just in case the suspension didn’t return to the car its exact right spot after I got out. Opps.

“shorter [students] getting the…lower body parts.”

Who sez short people got no reason to live!

That Beetle has a much higher poly count than a Cybertruck.

If only that had been around in 1972! Would have saved them so much time . . .

I’m going to sound pedantic but this seems more the first object rendered in 3D than scanned. Unless we consider measuring by hand scanning.

Still very cool info and while over my head, transferring the image to Polaroid is cool work around to the then current technology.

Still keep up the historical stories, it’s amazing to see how people, who I feel may have been genuinely smarter than us because their fall back wasn’t “then we used a computer”, made the first of things work.

I support the pedantry. This was modeled/rendered, not scanned.

see, I think the act of measuring IS scanning, just manually. It was still taking a real-world object and translating it into data. That’s scanning. It wasn’t just made in the computer.

Webster has a few relevant definitions:

2: to examine by point-by-point observation or checking

2a: to investigate thoroughly by checking point by point and often repeatedly

3a: to examine systematically (as by passing a beam of radiation over or through) in order to obtain data especially for display or storage

scanned the patient’s heart

radar scans the horizon

scan the photos into the computer

3b: to pass over in the formation of an image

the electron beam scans the picture tube

Using these definitions, I’d say pantographs would be the first “scanners” of 3D objects. They were invented in 1603 and are still used even today to measure and scale one image or object into another. I know plenty of machine shops that still use pantograph mills to trace reference objects (like gears for example), and then machine smaller or larger scaled versions of the reference.

Specific to your post though, CMMs (coordinate measurement machines) were invented in 1959, with 3-axis units in the 1960s. Those machines measure 3D objects and create a point cloud that was saved in a computer, so even then, this Beetle is definitely not the first 3D object ever scanned to create a digital point cloud file. It’s early, yes, not the first.

CMMs immediately came to mind when I read they measured all the points by hand.

Definitely gonna be 3D-printing one of these soon!

I had the exact same thought!

I was thinking about that myself! It’d be an object with a cool story.

Looking at the file, though, it looks like just a shell, which would probably take modification to make it solid enough to print?

Super cool! Would have never known that my interests in cars and 3D animation overlapped this way.

Man, that looks like the type of 3D model that gets it’s Money for Nothing.

Fun fact: The peeps who animated that music video, went on to found Mainframe Entertainment. Who produced both ReBoot, and Beasties (Beast Wars in the US).

At least the chicks are free

That ain’t workin’

Look at them yoyo’s. That’s the way you do it.

I love the polygons.

Do a barrel roll,

StarfoxOrlove!“Size of a VW Bug” was a standard unit of measure for boulders for years. And I thought it was a metaphor.

A few decades ago the larger boulders could have been “The size of a Chevy Truck”.

You know, “Like a Rock!”.

Some follow up nerdery from a fellow UofU alumn.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jjbax5HYHLQ

My neighbor growing up was Bob Ingebresten (who did the 3d titles for this hand film and was in the same program). Life did Bob dirty and he should have gotten the fame the other pioneers in this space got. He did eventually get an Scientific and Engineering award from The Academy, but he had a rough go in life. My dad always told me something about being cut out before the real profits could be had. I remember him working odd jobs setting up computers at banks and briefly owning a Neilson’s frozen custard. Dude was a genius but his great sin was poor self promotion. I actually remember his weird talking computers, we we make that thing say so many naughty words. I like to talk up his work when I get a chance.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_B._Ingebretsen

Also this

https://attheu.utah.edu/science-technology/precious-computer-age-relic-turns-up-in-u-storage-room/

Bonus points for people that actually want to try and run it

https://archive.org/details/utah_unix_v4_raw

And to think my COBOL class in my junior year at university in 1974, still had stacks of punched cards, and a computer that filled up a large room. Hmm….

Yeah. In 1975 I was a freshman taking Introduction to Computers. Stacks of punch cards, learning to write basic programs in BASIC (I was not a computer science major), and the time made available on the university’s mainframe for assignments was from midnight until 4:00AM. Wow, ch-ch-changes!

Utah represent! Now if we can finally get the credit we deserve for cold fusion!

Seriously tho, it’s wonderful to see that digital file exists and icing on the cake that they did the turn indicators. Thanks Jason.

Would love to know how things worked out for the students on that project.

Are you familiar with a little company called Pixar?

And here we are, all these years later, and all I have to do is run this file through Orca and I can have a model of Mrs. Sutherland’s Beetle.

That is pretty cool.While I have literally no clue how the technology works I can’t imagine how proud they all must have been.

Wow. This is an impressive feat given the technology available at that time.

Professor Sutherland unlocked the potential of his students by challenging them to do something that had never been done before. Those students have my respect for meeting the challenge.

Thank you for reporting on this gem Jason.