Imagine, you’re out on the trail. You’re enjoying a short break, when you see an old Jeep rattle by. Only, there’s something strange about it. It’s got a big old log strapped to its side!

When I first saw this out of context, I thought it was a traction thing. I assumed it was similar to the logs carried on tanks during World War II — logs that were used for filling ditches or otherwise clearing obstacles in tough terrain.

It turns out I couldn’t have been further from the truth. As it turns out, the log is actually an emergency repair. Let’s explore how a big chunk of wood can save your bacon in the backwoods.

The ‘Semi Float’ Axle

David was reminded of this surprisingly common repair after watching a video from YouTuber Dexter Browder, whom you might know from his popular DeXJs channel. Browder recently undertook a long day of wheeling at Windrock Park in Tennessee. Along the way, several Jeeps ended up battered and broken on the trail.

Chief amongst the wounded was a Wrangler, which suffered a critical failure. The rear left wheel was falling off the vehicle thanks to a broken rear axle. Visually, it’s a striking failure. It’s also quite a common one for certain Jeeps in hardcore situations (especially if the driver applies too much skinny pedal). It all comes down to a combination of weak shafts and the design of the rear axle.

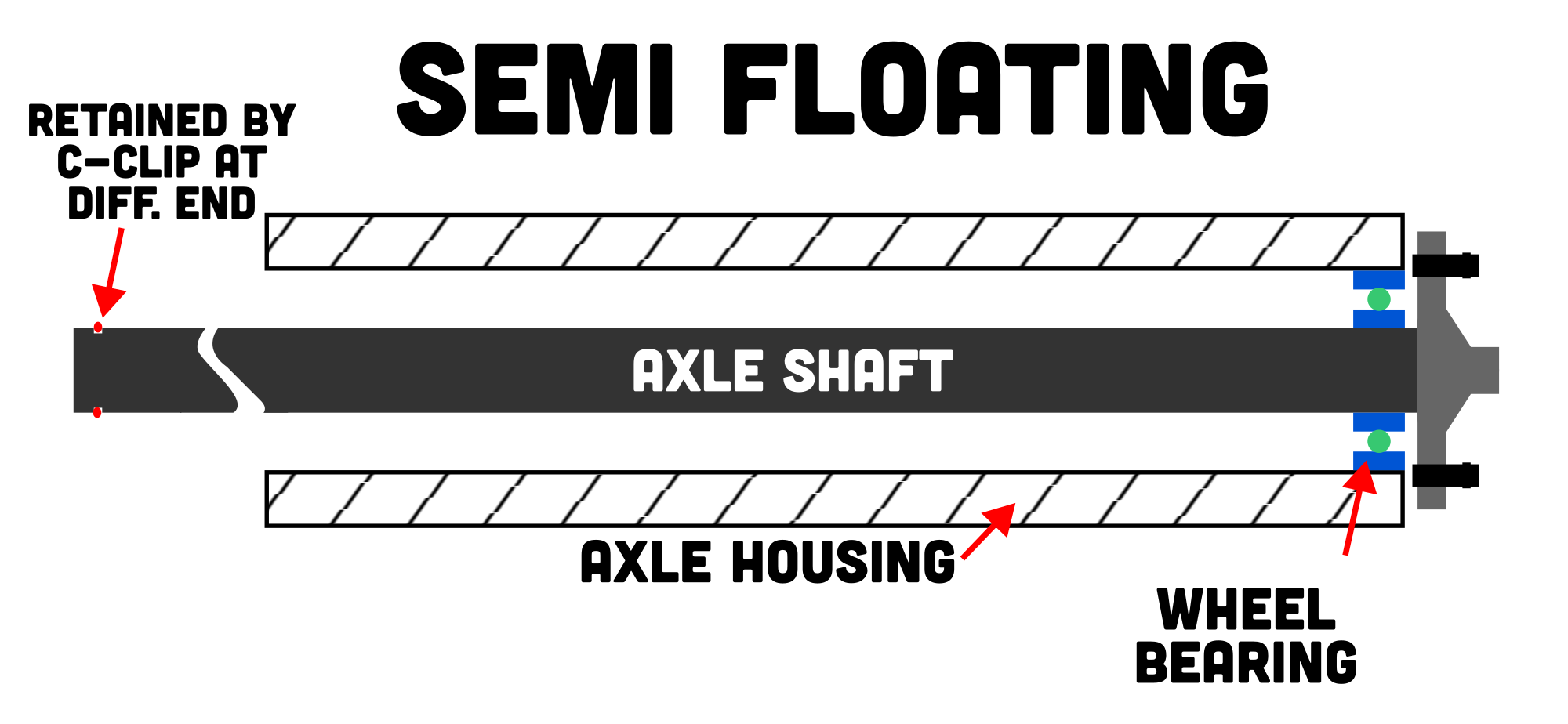

The Jeep shown above has the axle best known for such a failure: the Dana 35. These rear axles use what is called a “semi-floating” design, which played a critical role in the wheel coming off here. To understand why this happened, and why the log fix is so effective, we must explore one of the main differences between semi-floating and fully-floating rear axles.

It all comes down to how the axle shafts are held in place. In a fully-floating rear axle, the axle shafts are restrained from axial movement (i.e. pulling out) because they’re sandwiched between the differential gearing in the middle and the spindle at the end (the shaft has splines to transmit torque from the former to the latter). This design is very sturdy, thanks to the fact that the spindle transmits the weight of the vehicle to the axle housing/tube, with the axle shaft itself only having to handle transmitting torque.

A simplified diagram of a semi-floating rear axle assembly. Note how the axle shaft is retained by a small clip going into a recessed groove on the inside end of the shaft. If the shaft breaks, there’s usually little to nothing left holding it on to the vehicle. The shaft, with its pressed-on bearing, pulls out of the axle housing. Credit: Lewin Day

In a semi-floating axle, there is no spindle bolted to the end of the axle housing/tube to hold/sandwich the axle shaft in. Instead, the shaft is retained inside the differential with C-clips that prevent the shaft from pulling out. Toward the outer end of the inside of the axle housing, there is a single bearing that supports the axle shaft itself, and at the very end of the axle shaft is a flange to which the wheels mount. The wheel bolts to the flange on the axle shaft, transmitting the weight of the vehicle through the shaft, which then transmits that weight to the axle tube via the bearings.

If it’s still not clear, this video shows how a full-float axle’s axle shafts just sorta “float” between each wheel hub and the differential, and doesn’t have to see bending stresses from the vehicle’s weight, only torque from power transfer. You can see how, even if the axle were to break, the hub that the wheel is bolted to is attached to the axle housing:

Here you can see how the semi-float Dana 35’s shafts are held in place; each shaft rides on a bearing pressed into the housing, and the inside of each shaft is held into the differential with a C-Clip. You can imagine that, if the shaft broke, that axle (and its flange to which the wheel is bolted) would slide right out:

Thus, the semi-floating design introduces a unique problem off-road. If the C-clip fails, or if the axle shaft breaks, there is nothing else to retain the shaft to the vehicle. If this happens, the wheel tends to come off, since the wheel is fastened to the axle flange. The vehicle ends up with only three wheels, and usually winds up stuck.

That’s precisely what happened in this case and in so many others. It’s easy to see how the wheel has separated from the Jeep, and the axle shaft that has pulled out with it.

Indeed, from some angles, you can even see the outer brake drum, which is still attached to the wheel, while the brake backing plate and shoes are still attached to the axle housing itself. We don’t get a very clear look at the axle shaft itself, but it appears to have broken near the inside end. This is usually more common than the C-clip retainer itself failing, at least according to some anecdotal evidence from Jeep forums discussing the Dana 35 rear end. Whether it was the C-clips that failed or the axle shaft, the result is the same. The wheel comes off.

Enter: The Log

Unfortunately, when your axle shaft is busted and your Jeep is stuck on a steep trail, it can be hard to execute repairs. Few Jeepers carry entire axle shafts anyway, and popping open the diff to extract the broken parts and reinstall a C-Clip isn’t fun.

Thankfully, there’s a field-expedient repair that is both janky and perfect for this situation. What you ultimately need to do is find a new way to hold the wheel to the vehicle so that the shaft to which that wheel is bolted can keep riding on that bearing in the axle tube; this is where the log comes in.

The concept is simple enough. First, the wheel and what’s left of the axle are mounted back on the axle housing. A log is then placed along the side of the truck, pressing against the sidewall, with ratchet straps used to hold it in place. The wheel and axle shaft can no longer come out of the axle, because the log and the ratchet straps are pushing them back in.

If done right, the affected vehicle should be rolling at the very least. Driving is possible, but must be done slowly, due to the heavy damage to the axle and surrounding components. Going fast is a great way to rip the log and wheel right back off the vehicle.

Is it a perfect repair? Not by any means. For one, the log rubs against the tire and wheel. This creates wear and can puncture or otherwise ruin the tire in short order. Applying grease to the tire sidewall can help reduce this somewhat. Regardless, this fix can only work for short times at low speeds, or you’ll just rip the tire to pieces. One could imagine you might even set the log on fire if you drove too fast and built up too much heat. The fix would probably fail before you got that far, though.

You also don’t get any drive to the affected wheel. If you’ve got a locking differential, you’ll still get some drive to the other wheel on the same axle. However, if you have an open differential, you won’t get any meaningful drive to the opposite wheel. That’s because an open differential only gives the wheel with more grip the same amount of torque as the wheel with less grip. In the case where one wheel is disconnected from a broken axle, the differential is effectively delivering zero torque to that side, and so the other side will get zero torque as well. [Ed Note: You may as well remove the rear driveshaft at that point; of course, if you have a slip-yoke driveshaft that acts as a seal for your transfer case, that might not be a great move. -DT].

We’re told the Jeep in this video does have a locking differential. Still, the group decides to keep it hooked up to a tow vehicle to help it up most of the rest of the trail, since it’s severely crippled with one wheel out of action.

The log fix has other problems too. For a start, it’s quite unwieldy. If you’re on a difficult lumpy trail, there’s every chance you’ll catch the log on rocks or dips in the road, potentially ripping it off the side of your vehicle and causing further damage. It can also be difficult to execute, particularly if you’re in a smaller party. You need to be able to find a log, cut it to size, and mount it on the vehicle.

The off-roaders in this video used their vehicles to snap a tree down to size, but a saw or chainsaw is perhaps a more typical way to go. The fix naturally doesn’t work if you’re off-roading somewhere there aren’t any trees, fence posts, or metal pipes that you can use to do the job. You might also get in serious trouble for hacking up a tree, depending on the area you’re wheeling through.

This problem is why many hardcore off-roaders will upgrade to fully-floating axles. They’re usually less likely to break in the first place. Even if they do, they also don’t require such field expedient repairs in the event an axle does snap. Snap an axle shaft with a fully-floating axle, and it’s a minor bummer that doesn’t affect the ability of the vehicle to roll. Do the same with a semi-floating axle and you’re stranded until further notice. [Ed Note: There are plenty of semi-float axles that are much more robust than the Dana 35. The Chrysler 8.25 or Ford 8.8 come to mind. -DT].

Still, the log fix (used quite often, as seen in the YouTube video above by Enrique GuOr) is a useful hack to keep in the back of your mind. One day, you might find yourself stranded with a wheel dangling off your rig. With a few straps and a bit of know-how, you’ll be able to get yourself rolling again. Just don’t expect to see a lot of smiles when you limp past the ranger station on your way out.

Top image credit: DeXJs via YouTube screenshot

That youtube video at the end was a blast from the past. 4:3, plain white ‘Windows Movie Maker’ lettering, spelling mistakes galore. All it needed was a 009 Sound System song and it’d be straight out of 2008.

4:3… Ha!

I wish we’d have known this forty-odd years ago when driving a fully-laden GMC van across the deserts of SE Oregon in mid-winter. Handling got weird and then the brakes just quit altogether. Fortunately, we were crossing a Pleistocene lakebed, so flat as a pancake. We let the van roll to a stop, which was when we discovered the left rear axle and wheel riding about two feet outside of the vehicle. We spent the nest forty miles taking turns walking beside the van and kicking the wheel back in as it tried to back out–in sub-zero weather.

We made it to the hamlet of Lakeview, OR, where a friendly junkyard guy helped us find the C-clip that had gone away and were back on the road the next day.

Of course, this trick wouldn’t work well while driving across a giant extinct lakebed, as there are no trees.

That’s quite amusing to read after the fact (and I’m sure quite harrowing at the time). Great story.

That was pretty much just an average road trip for a bunch of young long-haired-weirdo-hippie-types back in the ’70s. We had nothing but beaters to go “overlanding” back then.

This all seems like a nice day ruined. Rescued, but ruined.

Oh yeah. The whole video series covers how some of the drivers massively underestimated the length of the trail and it got pretty wearing.

Oh yeah. Off roading is not my thing. I enjoyed reading your article, but I wouldn’t want to go through any of that.