If you’re reading this website, you’re probably already familiar with how Lexus broke into the American market in the early 1990s, making a huge splash with its revolutionary LS400 sedan. The LS arrived on the scene with all of the same luxury appointments you’d find in a 7 Series or an S-Class, but for just a fraction of the price, and with a lot more reliability. The car’s rise to prominence is a widely known tale that you can read about in dozens of publications, including this website.

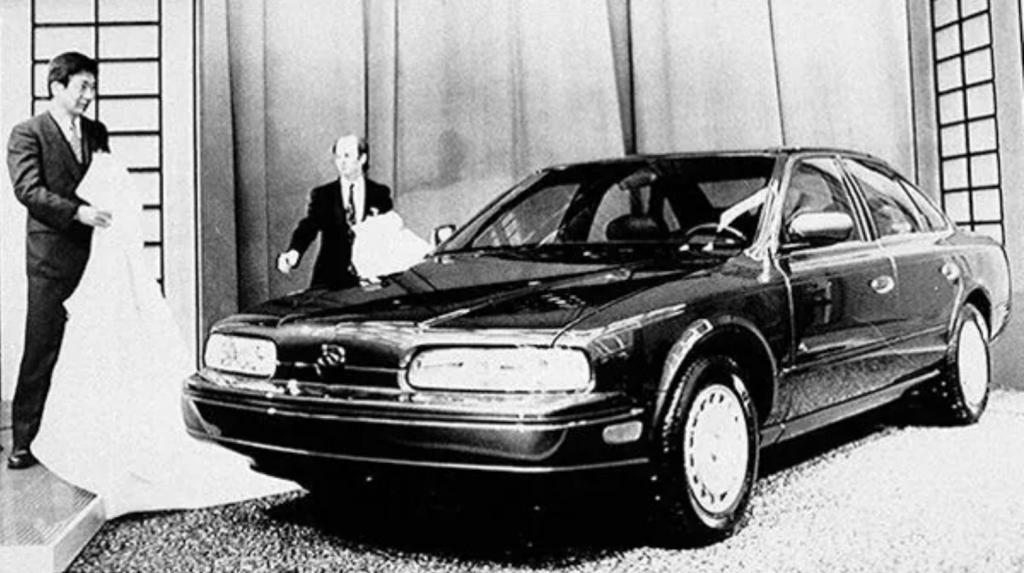

But Toyota, Lexus’s parent company, wasn’t the only Japanese brand that attempted to break into the luxury space in the 1990s. Nissan pulled a similar scheme starting in 1987 with the formation of Infiniti. Like Lexus, Infiniti launched in America with two cars; its goal was to encroach on the massive market share held by German luxury brands at the time.

Infiniti’s flagship car, the Q45 sedan, didn’t quite make the same impact as the Lexus LS. But it introduced the American public to a piece of tech that’s now ubiquitous in the modern luxury segment: Active suspension.

A Short History Of The Q45

The Q45 was one of many vehicles introduced by the Nissan brand following a huge overhaul of the company’s product line in the late 1980s. It was to lead the company to new heights in the U.S., joined by cars like the 300ZX, the 240SX, and the Maxima—all cars that have since outshined the Q45 in the automotive zeitgeist.

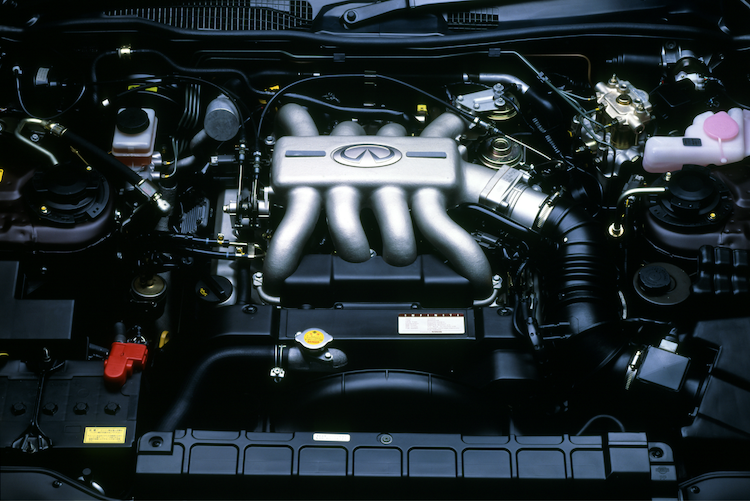

Infiniti’s big, luxurious sedan checked many of the same boxes as the LS. Both cars had naturally aspirated V-8s that sent power to the rear wheels, matching the layout offered by German competitors. The Q45’s was the VH45DE, a 4.5-liter unit that made 278 horsepower—28 more than the Lexus. The Infiniti even offered something the Lexus didn’t: Nissan’s well-known Super HICAS four-wheel steering system, included as part of the available Touring package, which also added forged alloy wheels and a rear spoiler.

Unlike the Lexus LS, which relied on stately, subdued lines, the Q45 was far more brash with its styling. In addition to the more rakish stance and sportier profile, early models famously came with no front grille. Designers told Car and Driver they spent twice as long finalizing the design as they normally would’ve on a new car. That time proved unproductive; while Lexus sold 41,000 LSs in the first year of production, Nissan sold just 14,000 Q45s, according to Consumer Guide. Infiniti would revise the front end to include a more traditional (and in my opinion, far less interesting) grille design for 1994.

The lower sales likely had something to do with the Q45’s price. While it was still far cheaper than anything with a Roundel or Tri-Star badge on the nose, the Infiniti was $3,000 more expensive than the Lexus, with a starting price of $38,000 ($93,718 in today’s money).

The Active Suspension Revolution

Active suspension aims to provide the best of both worlds. Using adjustable dampers or springs (or a combination of both, these systems can use a variety of sensors in the car to relay information to a computer, which can then adjust the suspension to better suit the vehicle’s situation. The ideal active suspension will deliver a soft, supple ride on rough roads, and a taught, stable ride on smooth roads or while driving quickly through corners.

Manufacturers began experimenting with active suspension systems as early as the 1970s, but like many forward-thinking pieces of car tech, it made its first debut in Formula 1. Lotus began development of an active suspension for its top-level race cars in 1981, before debuting it in 1983 at that year’s Brazilian Grand Prix. But it didn’t prove as effective as the company had hoped. From Motor Trend:

In theory, the system could raise cornering speeds considerably (Lotus engineer Peter Wright was famously quoted as saying its active-suspension F1 car could go around “any corner at any speed”), but in practice it reduced tire-slip angle so much that it was nearly impossible to get enough heat into the tires to allow them to function properly. The hydraulic system was also a bit of a horsepower pig, robbing 4 to 4.5 hp on a smooth road and up to 9 hp on a rough road. Add to that the computational complexity of the system and the need for aerospace-quality hydraulic actuators and you can start to see why this type of fully active suspension has yet to make it onto a mass-produced road car.

Still, automakers were determined to get active suspension tech into road cars. And so they did. As early as 1984, Nissan had a system called Super Sonic suspension, which used a sonar array mounted at the nose of the car and pointed at the ground to read the surface ahead of the tires. The sonar sensors would feed that data to the suspension, which would adjust damping as needed.

Mitsubishi was the first to get a true reactionary suspension system into a road car with its Electronically Controlled Suspension (ECS) in the Galant. That system was sold in Japan starting in 1987, before making its way to America through the VR-4 model in 1989.

The Q45 joined the Galant in 1990 to become among the first commercially available road cars in America with an active suspension system. Cars with the optional system were badged as the Q45a. Unlike the Mitsubishi setup, which used air springs, Nissan’s was hydraulically powered. In the above video, the always fantastic John Davis of Motor Week explains exactly how it works:

The Infiniti active suspension consists of an actuator at each wheel that does most of the work of the traditional shock absorber and spring. It is fed by an engine-driven oil pump. G sensors attached to a computer monitor the bounce, pitch, roll, and height of the vehicle. Signals are then sent to a pressure control unit that feeds hydraulic fluid to the wheel actuators as needed.

Pressure in some actuators may rise, while others are decreased. For instance, in a corner, roll is suppressed by increasing pressure to the actuators at the outer wheels and decreasing pressure at the inner wheels.

Basically, the system would react to the car’s position on the road and send hydraulic fluid to each corner individually to correct roll or pitch. That means in addition to lessening the severity of the Q45’s side-to-side lean, it could also improve dive angles under braking. It even had a “height” mode that could raise the car by 20 millimeters (0.78 inches) to clear particularly bumpy sections of road, not unlike an air suspension.

Davis, along with much of the automotive industry, praised the Q45a’s ability to deliver better handling, more stability, and superior performance over the standard Q45. On the surface, things were rosy. But like that Lotus mentioned earlier, things didn’t exactly work out.

Why Nissan’s Active Suspension Ultimately Disappeared

For one, Nissan’s system was expensive. It was offered on the Q45 as a standalone $5,000 option for the 1991 model year. That’s over $12,000 in today’s money, and would’ve been around a 10% increase in the car’s price out the door—not a great position to be in if the car is already more expensive than its closest competitor.

The system also added over 200 pounds to the Q45, according to Japanese Nostalgic Car. That hydraulic pump ran off the engine, so while it was improving handling, it was dragging down other parts of the car’s performance envelope. According to Motor Trend, the pump required 3 to 6 horsepower to run, adding 0.2 seconds to the Q45a’s 0-60 time, and slicing fuel economy by 2 mpg in the city and 3 mpg on the highway.

For most buyers, having a slightly better ride and slightly better cornering characteristics wasn’t worth the tradeoff. Infiniti expected just 15% of buyers to opt for the system when it was introduced, though it’s likely that fewer than that actually made the dive, as it was dropped altogether after the 1996 model year.

Still, the relevance of the Q45a can’t be overstated. It was the luxury segment’s first steps into the world of active suspension, paving the way for dozens of cars to offer similar systems for years to come. It was also ahead of the competition; Mercedes wouldn’t show off its first active suspension, the hydraulically-run ABC system, until 1996, when Nissan was phasing its system out of production.

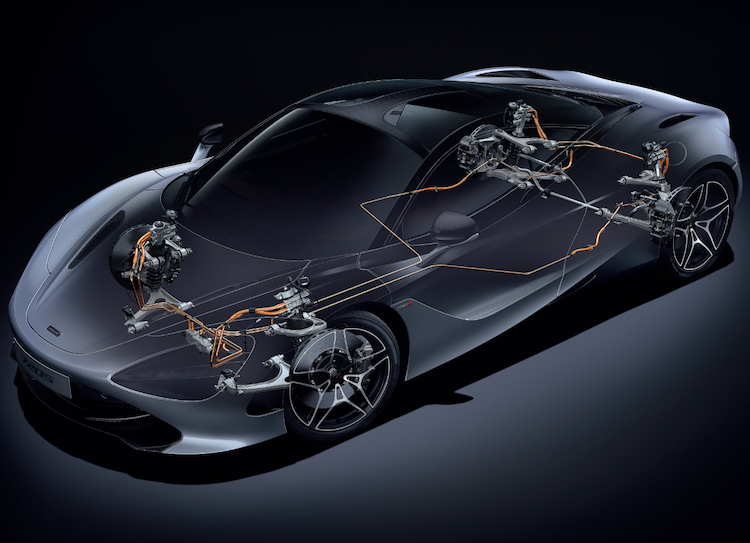

These days, you can find several vehicles with adaptive hydraulic suspension. McLaren uses a version it calls Proactive suspension, which uses a series of chambers for the fluid to isolate road impacts, at the same time translating roll to the rest of the car through a series of interlinked piping. It’s so good at this that cars equipped with the system don’t need roll bars. Then there’s Porsche’s newest system, called Porsche Active Ride. Each corner gets its own electric pump that controls how much hydraulic pressure is in the damper, effectively eliminating roll, pitch, and dive. Incredibly cool stuff.

Top graphic images: Nissan

Back in the 60s, I had a neighbor who had (in the US) a Citroen DS 19 or 21 wagon, and elementary school age me asked about how it sagged down overnight. Because minimally OCD me noticed it. And then I read in the car mags as a teen, how things in those systems could go bad and expensive.

I’m ok with a well-sorted suspension that handles most of what I encounter with cheaper components.

My ’17 Accord’s ABS handled going off over a rumble strip and into grass beyond the shoulder, when some idiot in a pickup came trying to pass, into my lane on a 75-mph two-lane highway in Texas.

I didn’t need active suspension. I just needed a well-sorted out basic suspension and a competent ABS system. And my Honda had that.

Active suspension would have not made that a better experience, nor a better outcome.

Then you’re missing out on the fun of hopping into your Citroen, starting the engine, and allowing the entire car to gently rise to ride height. It’s a great party piece, and a ridiculously comfy ride, that’s not wallowy.

It is fun to watch the rise.

i loved the leaves and babbling brook commercial. yen !

I had the pleasure of installing a car phone into one. What a car, IMO the subsequent “Q”s were not as good looking. As one does with a customer’s car that has like 50 miles on it, I dropped it into low gear and easily smoked the tires on the way to return it.

Company i worked at in 1991 sold 5 of these that year, and each one was a magnificent drive in and around LA. They were expensive and had maintenance issues, but until the first sign of trouble appeared, they were the best land yacht on the streets

In 1990, I received an “engraved” invitation from Infiniti to drive the Q45a for the weekend. Being a college student, it was the equivalent of Golden Ticket.

Infiniti didn’t stipulate any restrictions as long as the car was returned at 9 o’clock on Monday morning in same condition as before. A couple of my college friends rode with me while I drove all over the rural areas in North Texas and in Dallas like two parking valets and Ferrari in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off.

One of things was attempting the railroad crossing jump. The railroad crossing was about two feet higher than the ground so the road gradually sloped up to meet the tracks then down to the ground level. The action was, of course, illegal in Texas. I drove Q45a at about 40 mph and jumped. Instead of bouncing hard, the Q45a glided over the crossing gracefully. So smooth. We were amazed and tried a few times before moving on.

One of the roads was very pockmarked, but we hardly felt any jarring movement. There was a very windy and twisty road close to Denton: the car hardly leaned when negotating the curves.

I recall GM testing the Lotus system in one of its Chevolet K5 Blazer (1992–1994). Car and Driver had an extensive write-up about this Blazer. When transversing the off-road path, the engine and system kept faltering and stalling so often, rendering the Blazer useless. GM abandoned the project for a long time.

My dad picked up a 95 Q45 around 98 or 99. Kinda like Korean luxury vehicles of today, Infinitis resale plummeted after they left the lot. I inherited that car years later and maaaaaan do I miss those seats. Such a comfy ride. That V8 was no slouch either and made some great sounds. The six disc CD changer in the trunk? Don’t miss that. Antiskip could not keep up with junk roads.

Ah yes, from those bygone days when Nissan wasn’t a laughingstock.

Can I imagine the cost to repair the suspension system? Or is it : if you have to ask you can’t afford it.

Great idea, dumb application. Who is flinging their brand new luxury sedan around Laguna Seca?

When these came out it was still the days of speed limits enforced only by pothole in NYC, and a friend’s parents brought one or these. The thing was supernatural in it’s ability go around corners with potholes at speeds that would tear the wheels off any other car hitting them in a straight line. They were the perfect NYC car.

Now, if they had the power company dig up Laguna Seca, this would be the weapon of choice.

I love a first gen Q45 for sure. I still consider buying one as a commuter. I used to have an M30 that had active suspension as well, though I don’t know if it was the same system. It had “Luxury” and “Sport”, and it was so tired that though it made a difference, driving in Luxury mode was sketchy feeling, boat on rough ocean. Sport mode was tighter and reasonable to drive.

That’s not active suspension – it’s adjustable suspension.

Great article… I’ve always had a soft spot in my heart for those grille-less Q45’s. Nissan had a really great idea whose time was a bit too early in the market.

This is a very informative article, but I’m a bit wary of the part that states the Q45’s base price was $3,000 dearer than that of the LS 400, and that this was a factor in why the former didn’t sell well.

For one thing, the $35,000 LS 400 was practically a myth; it allowed Lexus to advertise a low entry price, but few were ever built that way. A customer looking for the $35,000 LS 400 in the early days of that model was unlikely to find one.

For another, the base price of the LS 400 rose to roughly $51,000 by 1994, in part due to the Japanese bubble bursting, but also likely in response to the demand for the car.

Third, given how poorly received the—in particular—grille-less Q45 was, it’s probable that Infiniti dealers and Infiniti itself were putting big discounts upon it to move metal, potentially making it quite a bit less expensive than the popular LS 400. This isn’t unlike modern times, where in theory a Lexus GX 550 acquits itself well against something like an Audi Q7 on price, but not when the GX 550 has markups and year-long waiting lists, or is frequently found pre-owned with low mileage for a $10K price hike over the as-new MSRP. At the very least, you can get a discount and favorable financing on a Q7 quite easily; not so on the GX 550. It was probably like that back in the day for the Q45 versus the LS 400, too.

And finally, as a corollary to point 3, people will pay whatever for something if they like it enough. See, again, the aforementioned GX 550, which really is quite a hassle to purchase compared to other stuff in that segment, and yet people are lining up around the block for the privilege of taking whatever unit is in stock (Lexus generally does not let customers or even dealers order specific cars). I think that if the Q45 had been a compelling product, it wouldn’t have mattered if it was a little bit pricey.

You’re right about the difference between LS400 and Q45 – but some additional details:

Lexus ads showed a handsome sedan.

Infiniti ads showed fallen leaves and rocky streams.

Lexus had a formal grille and looked like a Mercedes-Benz S Class.

The Q45 had a Cowboy Belt Buckle and looked like a Ford Crown Victoria.

(even the Q45’s counterpart in Japan – the Nissan President – had a grille)

The Lexus had California Walnut trim while the Infiniti had a black plastic dash.

Luxury buyers expected wood trim.

The base LS400 had cloth seats – yet were rarely built in such a way for the US. The Infiniti had standard leather seats – so it’s base MSRP was higher in that regard.

Lexus heavily subsidized the LS400 – initially selling them at cost (or less?) in order to make a name for itself. The Q45 had a traditional markup – so a higher price again.

Lexus impressed by promising free coffee and free loaners (that’s primarily what the

Toyota VistaES250 was for) in the service bay.Infiniti called a cab for you – and hoped you’d buy a

Nissan LeopardM30 for your wife.It’s a no-brainer which car luxury buyers wanted and why.

You are spot on. I remember, those Infiniti commercials, they were awful. Lexus was showing ball bearings going down perfectly fitted panel gaps and Infinity showed us rocks and ferns and crap. This was also the time period when Nissan was building a very capable and popular Nissan Maxima 4DSC (four door sports car) for several thousands less money.

Ah yes – the stacked champagne glasses on the hood, and driving down a train track while not on the tracks at all:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X1vZenBX4-0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ez_lCEEwSw4

spot on. It has always been interesting how, back then, Nissan could build such an amazing product, but then completely botch the sales. Those ad campaigns were truly horrible. The motoring press (back when we read about these things in magazines) generally said the Q45, and especially the later model with Gatling gun headlights, were superior, but always sold worse.

Hey shout out to my GX 550 Overtrail… Still worth paying $3k markup. I have had it for 19 months / 19,000 miles already and got one of the very first in the nation. They now cost way more, so even with markup I paid less than if I didn’t today.

Used car shoppers don’t look at new and vice versa. The used market is insanity in a different way than new. It’s really silly, but true.

No mention of the Citroën Xantia Activa V6 with its nearly unbeatable moose-test performance? Truly the pinnacle of Citroën suspension. Later C5s never quite lived up to the hydractive dream.

Jonathan Price was the adman for the early Infinity commercials as well.

Those first Q45s without the grille are just “chef’s kiss” perfect.

So true. I wonder how practical it would be to drive one today.