The American superhighway is a legendary marvel of engineering. These highways carry all sorts of cars, trucks, buses, and more safely and quickly across the country. If you’ve driven across Pennsylvania at all in the past 85 years, chances are you probably paid to run on the Pennsylvania Turnpike. This highway might not seem like much today, but when it opened in 1940, it was America’s most advanced highway. Later, it also became arguably one of America’s safest.

America’s superhighways — generally, divided high-speed highways with multiple lanes heading in the same directions — line the country, and enable you to connect any point in America by car with ease. These highways range from the compact, with two lanes in both directions, to gargantuan, with the capacity to move a mind-boggling number of cars per day. America’s widest superhighway is probably a section of Interstate 10 in Texas, where, west of Houston, the highway grows to 26 lanes, if you include frontage roads.

Most Americans probably never think of these highways, except when their respective jurisdictions raise toll rates, or when travel times creep up due to construction or congestion. Certainly, I would be willing to bet that you were not thinking about highway engineering while stuck behind a semi-tractor going 70 mph, that’s passing another semi going 69 mph.

But if you look past all of the boring or aggravating parts about trying to drive long distances, highways are actually awesome. Everything serves a purpose, from the spacing of the lines to the rumble strips lining the shoulder. There’s one highway that Americans can thank for innovations that they take for granted, and it’s the Pennsylvania Turnpike.

Getting Over Mountains Used To Be Hard

The Pennsylvania Turnpike recently celebrated its 85th birthday. Just after midnight on October 1, 1940, the Turnpike opened to the public, and it was an engineering project so grand that it received national attention. Today, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, as well as many historians, consider the PA Turnpike to be the nation’s first-ever superhighway. Let’s take a look at how Pennsylvania made history.

As the story The Building of the Great Pennsylvania Turnpike, by Pauline Shieh and Kim Parry, notes, Pennsylvania’s unique geography had long been a barrier to efficient travel in the region. In the late 1700s, Pennsylvanians rode on horses and in carriages to traverse treacherous, muddy roads and roads constructed out of logs. The greatest challenge to travelers back then was getting over the Appalachian Mountains. These mountains were nearly impassable back then, which made travel between western and eastern Pennsylvania inefficient, if not sometimes impossible.

Engineers throughout Pennsylvania’s history have found clever ways to defeat the mountains. At first, a canal system was constructed, which carried people and cargo through the mountains. Trips across the mountains that might have been near-impossible in the past became executable in only days. The canals were only the start.

In 1834, the Allegheny Portage Railroad began service as the first railroad to traverse the Allegheny Mountains. The Allegheny had only 36 miles of trackage, but it was enough to cross the difficult terrain divide between the Ohio and the Susquehanna Rivers.

In 1854, the Pennsylvania Railroad completed the iconic Horseshoe Curve (above), which greatly reduced travel times through the mountains by reducing the grade that westbound trains would have to climb. The line measures 31.1 miles and was constructed by men using only basic tools and animals. The Horseshoe Curve is such a big deal to traversing the mountains that it remains in heavy use today by the Norfolk Southern Railway. The curve is also considered to be such a marvel that there has been an observation area on the curve since 1879.

The invention of the automobile didn’t change much, at least, not at first. As The Building of the Great Pennsylvania Turnpike notes, early roads in Pennsylvania were primitive, and it would take days for a car to travel through the mountains, if you even made it. Changing weather conditions in the mountains made what few roads existed dangerous. Taking a train was still just the better way.

From Rails To Road

As early as 1910, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission says, plans were being pitched on how to fix the problem. The idea was to turn a railway that never really existed into a road. From The Building of the Great Pennsylvania Turnpike:

Two companies controlled the railroad industry on the eastern side of the United States during the 19th century. One was the New York Central & Hudson River Railroad Company (NYC&HR), and the other was the Pennsylvania Railroad Company (Pennsy). During this time period competition within the railroad industry was fierce, and there were several strategies the companies employed to gain a competitive edge. It became common practice to build new tracks, expand railroad tracks, or buy the stock of newcomers to force the competition out of business. These tactics would later provide significant routing for the creation of the PA Turnpike.

At the time, William H. Vanderbilt, the owner of the NYC&HR, felt his company’s main competitor was intruding upon his territory near the Hudson River. In order to gain the upper hand, Vanderbilt decided to construct the South Pennsylvania Railroad. The new railroad was to run directly parallel with the Pennsy’s main line to create competition and prevent a monopoly in that part of PA. A lot of people were excited by this project because they felt the Pennsylvania Railroad’s freight rate was too expensive and the additional competition would prove to be beneficial for all. The project was backed by steel magnate Andrew Carnegie since he too was angered by the outrageous rates the Pennsy was charging for transportation.

However, this project was abandoned in 1885 when J. Pierpont Morgan, a board member of NYC&HR and a powerful financial banker, convinced both railroad companies to come to a truce. Morgan felt that the completion of the South Pennsylvania Railroad would potentially hurt the company’s profits. Upon hearing the news, workers of the South Pennsylvania Railroad simply stopped working and walked away from the work site. This aborted venture of Vanderbilt has become known as “Vanderbilt’s Folly.” The semi-constructed railroad lay unused for over 30 years, until William Sutherland of the Pennsylvania Motor Truck Association and Victor Lecoq of the State Planning Commission decided the PA Turnpike was to be built in the 1930s from Vanderbilt’s abandoned railroad project.

Before the project that would create the PA Turnpike launched, Pennsylvania had attempted other ideas for getting cars through the mountains. One was the Lincoln Highway. Created by Carl G. Fisher and dedicated in 1913, this highway stretches from Times Square in New York City to Lincoln Park in San Francisco. The route, which currently spans 3,389 miles across 14 states, was also a testbed for America’s first superhighway. A stretch between Philadelphia and Pittsburgh operated as a toll road, but the road was peppered with sharp curves and slow speeds due to the fact that its routing followed old wagon trails. Increasingly few drivers were interested in paying for such an experience. The Lincoln Highway would fail to become a superhighway, but it remains historically significant in its role for connecting much of the country.

The challenges of existing highways were part of why the PA Turnpike was such a major triumph. Wagon trails were simply unsuitable as high-speed road networks. Inspiration would come from the Bronx River Parkway in New York. Completed in 1925, the Bronx River Parkway was America’s first express highway. Even as the skies’ clouds drew in and America fell into the Great Depression, cars remained a popular and growing fascination. Yet, Pennsylvania didn’t have a solution for people who would rather drive across the mountains than take a train.

Reportedly, these were among the motivations behind William Sutherland and Victor Lecoq going to state Representative Cliff S. Patterson to pitch their idea for Pennsylvania’s road of the future. When plans were hatched to build a proper road across the mountains, the abandoned Southern Pennsylvania Railroad lines seemed like a good fit. The grades were fit for trains, which meant that cars wouldn’t have much of a problem. Nine tunnels were built for the rail project, too, which could also be repurposed for cars. This would also save money on building costs, which was important because the legislators who greenlit the project did not approve of state funds being used for it. Though apparently, the existing tunnels did need repairs and boring.

America’s Most Innovative Highway

Pennsylvania Governor George Earle signed the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission into existence in 1937. Reportedly, getting funding for the project was difficult due to its wild ambitions. The plan called for a 160-mile route from Carlisle to Irwin, and a project of this magnitude had never been done before. Luckily, President Franklin D. Roosevelt liked the idea of the Pennsylvania Turnpike as a way to reduce unemployment.

Now with federal government backing, the highway was on, and construction broke ground on October 27, 1938. Six of the nine unused railroad tunnels and some of the rail bed were used for the PA Turnpike. It would take just 23 months for the initial tollway to go from the beginning of construction to being open to the public. Some 15,000 workers and 155 construction companies from 18 states took part in the mammoth project.

What’s fascinating is that the highway’s engineers didn’t just punch a road out onto an abandoned rail line. The Pennsylvania Turnpike was designed to be the ultimate driving experience. The highways of the 1930s were often built to inconsistent standards, with one highway being built somewhat differently depending on when and where it was built. The engineers of the Pennsylvania Turnpike did away with that, and the entire 160-mile length was built to the same standards.

These standards were forward-thinking for their day. The PA Turnpike was designed as a limited-access, divided four-lane highway with no speed limits, no grade crossings, no intersections, and no stop signs. Drivers entering the highway would have 1,200 feet to accelerate, and drivers exiting would have 1,200 feet to brake. No grade was to be greater than three percent, curves were to be wide and banked, and signs were to be big so drivers could read them at high speed. The engineers were even exacting in the pavement design, which was to be exactly 24 feet wide in each direction, plus two 10-foot wide shoulders in each direction.

Small changes made a huge difference. The 11 interchanges on the highway had lighting so drivers could safely navigate them, there were guardrails, cat’s-eye reflectors on signage, and the highway even cut down on distractions by banning billboards.

The engineers even thought about how there weren’t many gas stations or restaurants in rural Pennsylvania, and decided to erect service plazas where motorists could fill up their tanks and their stomachs.

Drivers Go Nuts

All of this was done on a mission to create one of the safest, most satisfying road trip experiences in America, and the response by the public and the news was grand. From The Building of the Great Pennsylvania Turnpike:

Following the ceremony that signaled the start of “America’s Superhighway” in the late 1930s, Turnpike Commission Chairman Walter A. Jones and his crew were approached by a woman asking for their autographs. Puzzled by the sudden celebrity treatment, Jones asked the reason behind her request. The woman replied, “…so that my children can say that they saw history being made that day when the greatest highway, a new era of road building, was started.” Those words were spoken by a farmer’s wife whose land was bought to build one of the biggest expansion projects ever to connect roads across the state, the Pennsylvania Turnpike. The woman’s words reflected the hopes and dreams of many Americans who had been eager to see the completion of the freeway.

People came in droves from all over to be the first to travel the Pennsylvania Turnpike on its opening day. The Harrisburg Telegraph described the event to be like the beginning of a car race: “At midnight, two black cats ambled across the gleaming cement. A minute later, a ticket-seller dropped his arm in the gesture of an automobile race-starter, and traffic was under way.” The first traveler to pass through the Carlisle toll booth was Homer D. Romberger, a native Carlisle feed and tallow dealer, and Carl A. Boe of McKeesport was the first at the Irwin interchange. It’s interesting to note the first two hitchhikers on the PA Turnpike, Frank Lorey and Dick Gangle, were picked up by Boe shortly after he had gone through the turnstile. There were many other firsts on opening day and everyone wanted their chance of fame.

Unlike today, there was no established speed limit when the turnpike opened and motorists excitedly recounted their tales to others of traveling the highway at speeds up to 80 or 90 MPH. One Ohio trucker who feared getting a speeding ticket remembers his first run-in with the police on the PA Turnpike: “I was going down one of those grades at 70 to 80 miles an hour. I looked in the mirror and saw a white car following me. I didn’t know whether I was going to get arrested, so I pulled off the road as though to take a rest. The white car pulled off, too. An officer got out and asked me, ‘How do you like the road?’ I said, ‘It’s very nice – I guess I get a ticket.’ The cop told me, ‘No, we aren’t interested in the speed limit. As long as you stay on your own side and watch yourself, we won’t bother you.’” However, speeding did begin to pose a problem and a 50 MPH speed limit was imposed.

Reportedly, critics of the project thought it would be a failure, just like the Lincoln Highway’s toll road, and estimated that fewer than 800 cars a day would drive the newfangled PA Turnpike. They couldn’t have been more wrong.

The PA Turnpike estimated that in just its first four days of operation, a whopping 240,000 cars drove on the tollway, and the state collected $140,000 in revenue. That was all from vehicles paying only a penny a mile to experience America’s first superhighway. The PA Turnpike had a little something for everyone, from the families who wanted a safe way to drive across the state to the car enthusiasts who wanted to see how fast their cars could really go. A road where a car enthusiast could go top speed for 160 miles was unheard of at the time.

The PA Turnpike says that the public’s obsession with the turnpike was so wild that people drove the turnpike’s entire length both ways just for the fun of it, and families parked their cars on the side of the highway to enjoy picnics next to the cars and trucks thundering down the road at top speed.

The Turnpike Continued To Innovate

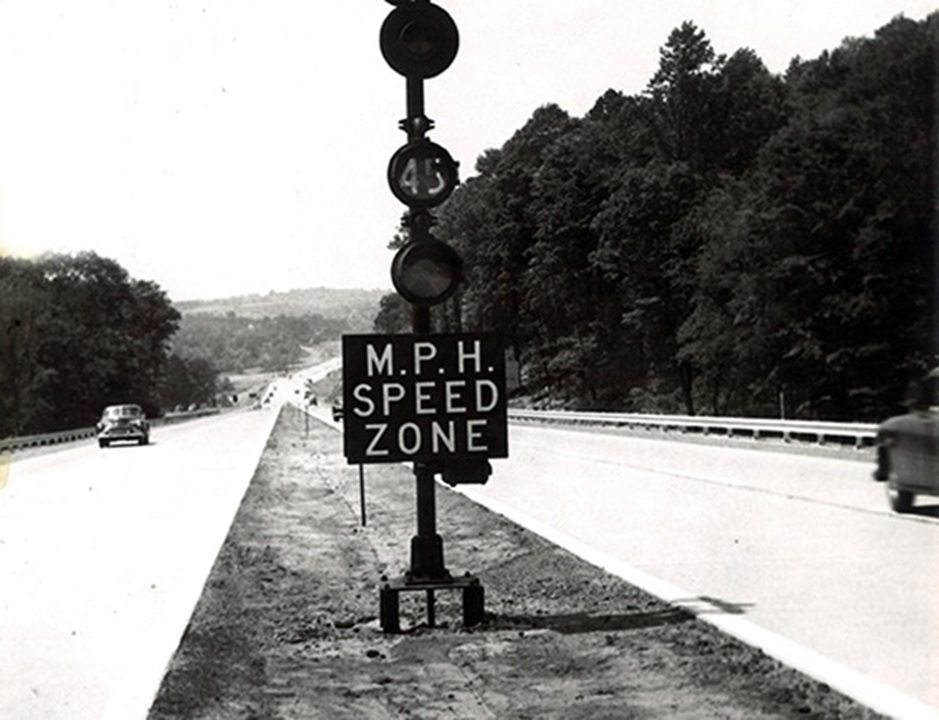

The PA Turnpike would also become known for further innovations. When Turnpike authorities learned that there were a high number of crashes on bridges, they installed special speed limit signs in the median to slow bridge traffic down to 45 mph. Turnpike traffic would pick up after World War II, and authorities observed a huge spike in head-on collisions. This led to the installation of guardrails in the median.

But perhaps the biggest advancement came in the 1980s, when bridge engineer Neal E. Wood invented the Sonic Nap Alert Pattern (SNAP), an improvement to the rumble strip, configuring it into something capable of waking sleeping drivers before they crashed. From the Federal Highway Administration:

The idea for SNAP originated with the author’s review of police accident reports, looking for engineering modifications that could improve safety. Early in 1984 it became apparent that Drift-Off-Road (DOR) accidents constituted a significant safety problem on the PA Turnpike. Some individual observations on the Turnpike and preliminary research led to a 1984 sketch of the original SNAP concept.

Study of existing intermittent rumble strips showed that effectiveness depended on a continuous pattern. Since the Turnpike has a “bare pavement” snowplowing policy, any form of raised pattern was eliminated and only indented patterns were considered. Also, a narrow pattern was necessary because maintenance vehicles travel the shoulders daily for debris collection and the pattern should not encroach on their wheel path. Thus, a narrow SNAP was proposed in the original 1984 sketch. Upon seeing the sketch, the Turnpike’s chief engineer thought that it had potential, but would require testing.’

During August 1985, tests were conducted on several indentation methods along the shoulder near one of the Turnpike’s Maintenance facilities. Using a pavement heater, an indented pattern was “raked-in,” similar to the proposed SNAP, which resulted in a loud noise and perceptible vibration in vehicles driving over the pattern. In the meantime, a Federal Highway Administration report (1) had been secured that indicated other states were experimenting with rumble strip designs to alert drivers that were drifting off the road. The report described a variety of test installations, but was not conclusive on specific designs or future tests.

Part of what made SNAP an important evolutionary step in rumble strips is that Pennsylvania tested out a variety of strip widths and depths until engineers found a configuration that was loud enough and drivers favored. The result? Drift-off-road accidents were reduced on the Pennsylvania Turnpike by 70 percent.

A Template

The Pennsylvania Turnpike would become even more historically significant because other highway engineers found the Turnpike so impressive that it would become the template for other American superhighways. Innovations that were tested at the PA Turnpike, like SNAP and service plazas, would also be used elsewhere. Pennsylvania claims that the towns surrounding the Turnpike also continue to see growth, and so the highway isn’t just good for cars.

The PA Turnpike has evolved dramatically over the years, with modernization efforts, bypasses, and open road tolling. Today, the PA Turnpike feels like any other highway, and so unless you knew its history, you wouldn’t know that the Turnpike is a big deal. I drive on the PA Turnpike every single time I drive to Baltimore, and even I only recently found out that it’s a real piece of history.

So, the next time you find yourself getting lunch next to a highway, or see a driver successfully awoken by rumble strips, thank the engineers of the PA Turnpike. 85 years ago, a 160-mile highway meandering around the mountains of Pennsylvania was at the apex of road engineering.

Top graphic image: Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission

Great article!!! I don’t have anything insightful or witty to say – just wanted to say thanks for great writing!

Having recently driven around Belgium, I now love our highways more. Obviously they have motorways as well, but not enough of the damn things. The speed limit on the two lane roads feels like it changes every couple kilometers.

An article on the PA Turnpike and no mention of the anachronistic hell that is Breezewood?

I make the north south trip through Breezewood once or twice a year and have never once stopped at any shop there in protest.

I was forced to stop once when my 7 year old had just vomited in his lap, but that is the level of emergency it takes for me to stop.

My strongest memory of the PA Turnpike is driving it in the Winter in my mom’s “66 T-Bird. It had sequential turn signals and electric windows & wind wings. The driver’s side electric window would fail sometimes. So, I remember taking the turnpike ticket by snaking my arm out the wind wing! Exciting times!

Great article, Mercedes. I spent a lot of my childhood on the original stretch of the Turnpike, going from my then home in McKeesport to my grandparents in Harrisburg, starting before the tunnels were double-bored and the Laurel, Rays, and Sideling Hill tunnel bypasses were built. And then I went to NJ for college.

My Mom used to go to Atlantic City with my grandparents, starting the first year. Apparently my grandfather drove like hell in his Chrysler (we were C-P dealers then.)

My Dad’s family farm is just east of Blue Mountain Tunnel, and the Zion Reformed Church where my ancestors are buried is right above the westbound lanes.

One thing I do miss is the original fieldstone service plazas, but at least Midway South was beautifully renovated and serves as a Turnpike Museum as well.

These days I mainly take the NJ Turnpike from Brooklyn to see my dad in Central Jersey. Also a damn fine road, not to mention the Garden State Parkway, an English romantic landscape you can drive through.

It’s an important highway, and you did a good job laying out its story, Mercedes. It also holds the distinction of being considered the most expensive toll road in the US. Since August I’ve been making bi-weekly trips from the Harrisburg area to Philadelphia, about 200 mile round trips. Tolls come out to about $25.00 per trip. Ouch! Without EZ-Pass it would be about double.

Apparently they don’t have to use the toll funds for the toll road (or any road) so now it’s just another tax. The 55 MPH speed limit in some sections is a joke (I used to live just off a main road with plenty of stop lights and business driveways with a 55 MPH limit).

One thing I’ve read is that road designers learned from the PA Turnpike to avoid creating really long straightaways, even though they’re more efficient, because they lead drivers to space out.

When railroads were laid out in the 1800s the big companies did their best in places like the Great Plains to make them as straight as possible to minimize fuel costs. But they had trained engineers and limited traffic, so spacing out was less of a risk. But people driving on the Turnpike, especially at night on limited sleep, had a way of zoning out on straightaways with potentially tragic results, so more modern highways tend to incorporate designs which keep drivers at least minimally engaged.

Awesome article. Spent a lot of my childhood on the Turnpike. We used that New Stanton exit every time we went to Maryland. I believe it was $0.75 cents back in the 1990s.

I only did the cross state trek twice on the PA turnpike. Once to go to Michigan because I figured why not (dont do it I got a nice toll bill) and the other time I needed to go to Kennywood near Pittsburg. I do take the north east extension because its fast and convenient. I’m really grateful Rendell’s plan to make I-80 part of the turnpike system failed.

Ah yes, the Pennsylvania Turnpike, the thing I never drive on because it would bankrupt me over time.

The non-toll way takes longer, but I don’t feel the time savings is worth the cost, especially when I’m towing a trailer almost any time I go out that way.

Although I have no interest in driving on it, I did like learning about its history from reading this.

This reminds me: hats off to the state of Kentucky, the only place in America I know of where toll roads were built to improve the state’s highway system, with the intention of sunsetting the tolls once the highways were paid for, then actually sunsetting the tolls. Yeah, right, you’re thinking, just like they said about that toll road or toll bridge in my area that I still have to pay to cross 50 years later, that has certainly been paid for a dozen times by now.

Well, Kentucky actually kept its word. My family moved to Lexington in 1987, and every time we traveled south to visit family, we paid the toll for the Bluegrass Parkway, to hit I-65 in Elizabethtown. By the time I was in college, the highway had paid for itself and the toll booths were closed.

Dear every other state and every other DOT: if Kentucky could do it, so can you. Either cancel the tolls on all those toll roads and toll bridges that have certainly been paid off by now, or simply stop being lying bastards and admit that you’re just going to keep on keeping the money.

As MAD magazine once observed in a comic when a driver complained at the toll booth that the road had been paid for several times over already: “But now you’re paying for the maintenance of the toll booths!”

Same with Dallas North Tollway (DNT) in Dallas, Texas.

Initially, the DNT was to be converted to freeways after the cost was amortised. However, the company that maintains DNT found a way to “delay” the conversion. It extended the DNT from LBJ (I-635) to Briargrove Lane in 1987. DNT keeps extending further and further to US 380 in Frisco, Texas, the current terminus (until the extension to FM 121 is completed).

15 or so yrs ago, we drove from Niagara Falls to NYC. We had the choice of taking the I-90/I-80 toll road or hwy 390 mostly 2-lane road that wasn’t a toll road. We took the non-toll road and got there in about the same time, but in an oddly more relaxing way. Driving through the country side at a relaxed pace was kinda refreshing after driving on interstate freeways for most of the trip.

The PA Turnpike also necessitated the creation of the PA Turnpike Commission, notable for prodigious levels of graft and corruption over the course of its existence.

When I was a kid and we were living in Michigan, the Pennsylvania Turnpike was the main route to get to/from my Granny’s house in Virginia.

It was my job to throw the coins into the bins at the toll plazas from the back seat.

I never missed.

Fond memories also of saying at the Holiday Inns along the way.

How I miss those old Great Signs, dinners in the restaurant where the hostess was always in a long evening gown, their Prime Rib special, and falling asleep to the sounds of cars & trucks rolling down the turnpike…

Both of my grandfather’s worked on the turnpike. Both of my grandfathers were miners that lost their jobs during the Depression. There were a LOT of unemployed miners available in Pennsylvania to build the turnpike.

The turnpike goes through hills all the time with sheer cliffs on either side where the workers have just blown a slot into the hill to install the turnpike. It’s a strong memory of driving or riding on the Turnpike to see those large cuts in the hills that seem to defy gravity.

Since the workers had a LOT of unemployed miners that knew how to carve rock into any shape they wanted using the power of explosives, the fact that these brutal hill cuts that are stable although not looking like they should be makes a lot more sense.

I remember moving to the upper midwest back in the 90s and driving from MN to Central PA and having the entire drive at 65+ and then hitting the OH PA border and having to slow down to 55 for the last 7 hrs of the drive and I always saw more state patrol in PA than MN, WI, IL, IN, & OH combined.

After the 55MPH speed limit hit in the 70s, the PA turnpike was reluctant to give up the moneymaker. You could expect a PA State Police cruiser to be parked on downgrades clocking traffic. I once saw three — one clocking traffic, and two others lined up to move into the same spot in turn. And they were still using rather ancient, large X-band radar antennas hung on the rear door window frames or drip rails. If you had a radar detector, you’d pick those things up a mile away — even from over hills because the output signal was so strong it bounced off the landscape everywhere.

I’m pretty sure they got an uptick in ticket revenue when they finally switched to more modern, harder to detect in advance K-band equipment before finally lifting the speed limit.

Some sections are STILL 55.

Honestly, that’s probably not a bad idea. There are some sharp and narrow curves in places, that aren’t in line with modern highway engineering and would be costly to upgrade.

55 on the whole thing was miserable unless you were a passenger, sightseeing.

I’m not talking about the dangerous parts (which I agree, should be 55). There are flat, 2 and 3 lane sections of 55.