For much of trucking history, fleets and owner-operators had to work around strict and short tractor-trailer total length restrictions that limited how much cargo they could carry within legal limits. Carrying less cargo means that a trucker cannot maximize their load and therefore their profits, and that just didn’t sit right with many engineers and companies. One of those people was Ronald Zubko, vice president for Strick Trailers. Fed up with length restrictions, Zubko set out to design a truck that was all trailer. This is the Strick Cab-Under, and it tried to make trucking more efficient by putting the truck under its trailer.

Total length restrictions used to be the bane of the trucking industry. Back in the 1910s, several states started setting their own rules for how heavy a truck could be. The problem was that these regulations often varied wildly. As the U.S. Department of Transportation wrote in 1997, by 1913, at least four states had truck weight limits. A truck driving in Maine couldn’t weigh more than 18,000 pounds, while a truck in Massachusetts was allotted 28,000 pounds. Pennsylvania’s and Washington’s limits were 24,000 pounds.

The U.S. DOT notes that it wasn’t long after that period when states began caring about more than weight, and started imposing regulations on truck length, width, and height. By 1929, most states had some sort of regulation limiting the size and weight of a truck. Most states agreed on 96 inches as the maximum width of a truck or a bus. By 1933, every U.S. state had limited truck size in some way, and the lengths varied the most. Many of these maximums were just the byproduct of early 20th-century infrastructure, where heavy trucks were more than capable of tearing up road surfaces.

How bad did it get? As I wrote in the past, Illinois once had a regulation that limited tractor-trailer total length to only 35 feet, which seriously limited the efficiency of profitability of trucks operating in the state. This was a huge problem because, as I wrote before, trucks that were legal in one state were not legal in another:

In 1935, Congress passed the Federal Motor Carrier Act, which gave the Interstate Commerce Commission the power to regulate the trucking industry on a federal level. Eventually, carriers had to file as private, common, or contract carriers. By 1938, the ICC regulated the number of hours a trucker or bus driver could drive in a single shift. Yet, the states still had the power to impose limits on truck length and weight. Even back then this was a huge headache because a truck that was perfectly legal in one state wasn’t legal in another, and in 1941 the ICC conducted a study on the impacts of this. Here’s a snippet of what the DOT found, as it was presented in the 1997 U.S. DOT Comprehensive TS&W Study:

. . . wide and inconsistent variations in the limitations imposed by the . . . States. . . [and that]. . . limitations imposed by a single State may and often do have an influence and effect which extend, so far as interstate commerce is concerned, far beyond the borders of that State, nullifying or impairing the effectiveness of more liberal limitations imposed by neighboring States.

The 1941 study concluded that the only logical path forward was federal regulations on size and weight limits because state laws were so wildly different that trucking companies ended up just building trucks to fit the laws of more restrictive states, anyway. After all, if your truck was built just for a looser state, it wasn’t legal to operate it in a strict state.

The federal government took some action in the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1956. The new Interstate Highway System established limits in the System, and the government allowed states with pre-existing maximums that were heavier than federal limits to run semis on interstates. Regardless, the length issue was still there because, as trucking periodical Overdrive Magazine writes, federal total truck length restrictions were set to 55 feet in the east and 65 feet in the west.

This patchwork of legislation is a major contributing factor to why cabover trucks–units where the cab sits over the engine and front axle–ruled the road for several decades. A typical American cabover had a smaller footprint than a conventional semi–one where the cab sits behind the front axle and engine, resulting in a “long nose”–which meant that trailers could be bigger and haul more cargo.

Cabovers, which were technically invented in the earliest days of the trucking industry, were an excellent way to maximize loads, increase efficiency, and keep more money in the pockets of fleets and owner-operators. But they were not perfect, as no matter how you sliced it, some of your extremely valuable maximum length was eaten up by the tractor itself.

Trucking history is full of attempts to cure this issue. In the 1940s and 1950s, car carriers in Illinois got so creative that they built innovative car hauler trucks where the cab sat feet above the engine, allowing the front end of a car to occupy the now-empty space that the cab would normally be.

Another creative effort includes the GMC DLR 8000 and DFR 8000 ‘Cracker Box’ of the late 1950s, which took the concept of the cabover to the extreme with a minuscule cab and impressive weight loss.

Then there was the Twin Coach CargoLiner of the 1950s, which is sort of like a self-propelled semi-trailer. That truck promised to carry the same load as a traditional tractor-trailer, but with a length that was eight feet to 10 feet shorter.

Perhaps the most extreme invention of the heavy length restriction era was the Strick Cab-Under, and it was built to do one thing: Carry the largest load it could within legal length limits.

A Pioneer in Trailers

One of the fascinating parts of the Cab-Under’s story is that this truck wasn’t built by a big name like Peterbilt or Kenworth, but by a company that built freight trailers that were pulled by those trucks. Here’s what Strick Trailers of Monroe, Indiana, says about its history:

The roots of Strick Trailers, LLC extend back to the 1930s, when Frank Strick first applied his knowledge of aircraft engineering to the trucking business. Strick built the first “frameless” monocoque trailer body — quite a revolutionary development at the time. Monocoque construction — and the use of aluminum rather than steel — led to bigger and lighter trailers, which meant more freight could be hauled by one truck. Today, that pioneering spirit continues with innovative trailer design and manufacturing techniques that bring you the finest dry van trailers on the road.

In the past, Strick sometimes found itself at the bleeding edge of shipping technology. In 1956, Malcolm McLean invented a standardized shipping container. His idea was simple, but brilliant. Until that point, all sorts of cargo of different shapes and sizes had to be strapped to a loading system and carefully placed into a ship’s hold. Cargo container size varied wildly. This system was slow and inefficient. In McLean’s eyes, the Maritime Executive reported, if most cargo could be loaded into standardized containers, the process of loading and unloading a ship could be made more efficient. Standardized containers would also be easier to plop down onto a truck to get the cargo to its final destination.

McLean is often credited as being the father and inventor of intermodal transportation, a system that the world of commerce still depends on today. Only two years after McLean’s creation, Strick tried its own hand at this idea with the standardized “Stricktainer.”

A Stricktainer was about half the size of a McLean container, which meant that a single truck trailer chassis could carry two Stricktainers. By the 1960s, Strick would rise to become the largest manufacturer of marine containers.

Another big milestone in that decade was the Strick Flexi-Van, which was a standardized truck trailer box that detached from its chassis to be loaded onto a flat train car. Yep, that’s another idea that remains in widespread use today. Strick was just one of the pioneers in the now massive logistics machine that works day and night around the world.

In the 1970s, Strick would attempt to reinvent the trucking industry.

The Cab-Under

According to Overdrive Magazine, it was 1974 when Ronald Zubko, vice president for Strick Trailers, came up with the idea for the Cab-Under. Zubko wasn’t just an executive at Strick, but also an engineer. Strick’s customers were always looking for ways to carry more cargo and still remain within 55 feet or 65 feet. The problem was that the length was a hard limit, so it wasn’t like Strick could just make a trailer longer. Making it taller wasn’t a realistic answer, either.

The only way was to move forward, literally, but, of course, there’s a whole semi-tractor in the way. That’s when Zubko realized that there wasn’t really anything governing the shape of a semi-tractor. From Overdrive Magazine:

“To me, a truck is a tool,” he says. “It’s not something that has to fit a certain aesthetic mold or configuration. It can be whatever it needs to be to get the job done.”

So, Zubko started dreaming and then drew up his idea. He came up with a truck that allowed the trailer to span the entire legal length of the truck. How? Zubko designed a semi-tractor that rode low to the ground and had a body like that of a sports car. The driver of this truck sat no higher than they would in a normal car, and above their head was the trailer with the cargo that they were hauling.

As Overdrive Magazine writes, Zubko took his idea to Sol Katz, the owner of Strick Trailers, who looked at the idea and told him it would never work. Katz said that such a rig would be horribly uncomfortable for the driver. Then, shortly after, Katz’s wife gave him a Maserati for his 50th birthday. Katz loved the sports car and its ride so much that, suddenly, the idea of the sports car of semi-tractors seemed appealing.

The project was given the green light. First, Zubko and his team made a scale model as a proof of concept. To make the first prototype, Zubko and two assistants took a brand-new International cabover and rebuilt it into pretty much an entirely different truck. This process took a year, and what came out of the other side was something almost otherworldly.

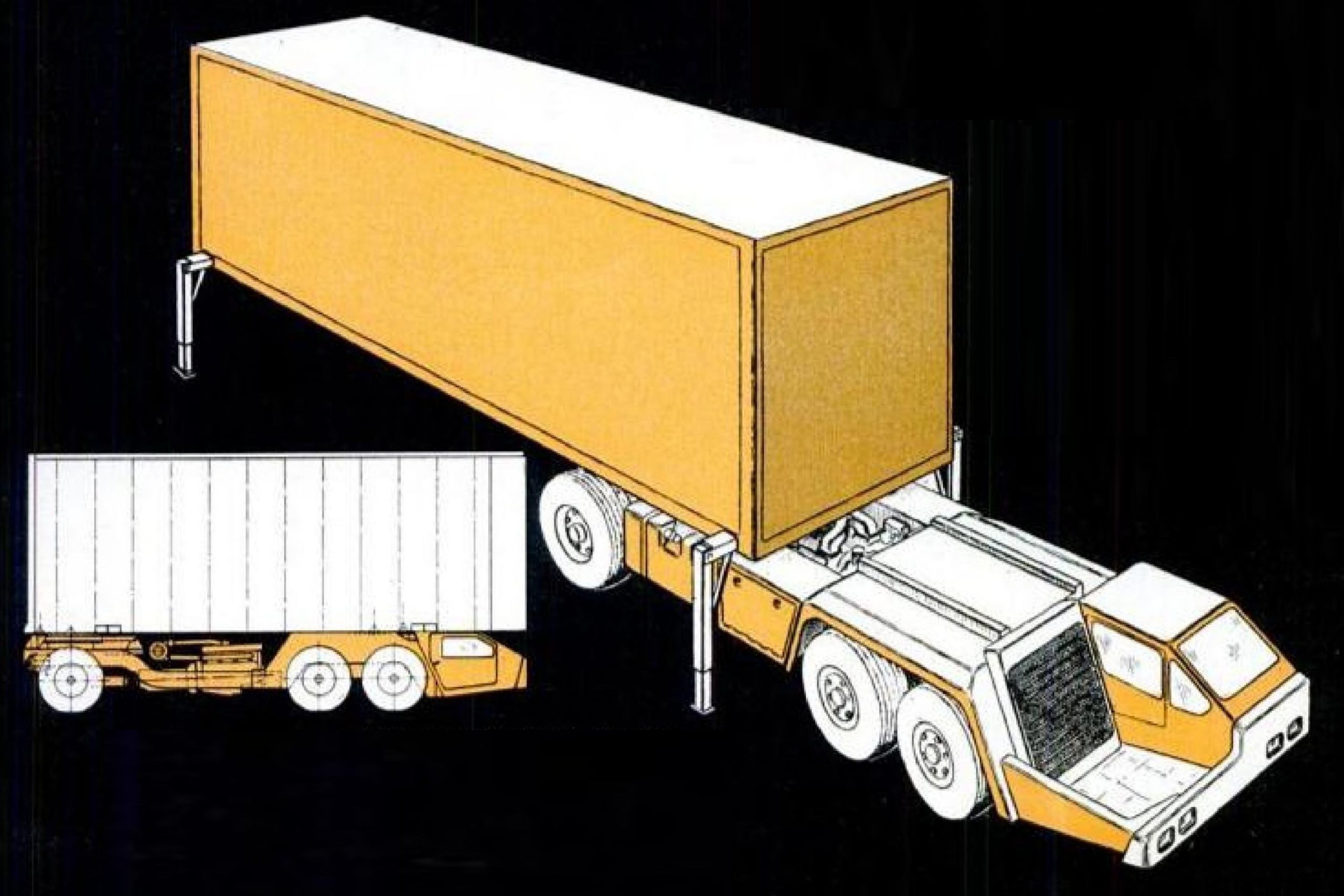

According to Overdrive Magazine, the first Strick Cab-Under rode on a special chassis, and the single-seat truck stood only 48 inches high. It also rode low with a ground clearance of only 8.5 inches to 9 inches. To get the truck to be totally flat, Zubko and his crew positioned the cab to be ahead of the front axle, and the Cummins 903 14.8-liter V8 diesel rode amidships behind the front axle. Shifting, at least in the production version, was supposed to be handled by a Fuller RT9513. The trailer would be parked on top of the flat truck. This configuration, Zubko said, would allow a trucker to pull double 27-foot trailers, ensuring that nearly all of the truck’s length was for cargo.

According to Strick, in order to get the truck to be so small, the engineering team designed the cab to mimic the interior of a sports car. This meant that the trucker sat in a semi-reclined position like they would in a sports car. When Zubko spoke to Overdrive Magazine in 2005, he said that if a driver of a Strick Cab-Under pulled up next to someone in a Chevrolet Corvette, they’d find that they’re in the same seating position as the Corvette driver.

Strick put the truck through intense testing, including having a driver pilot the truck across America for six months. That was after the truck drove Strick’s test track in East Liberty, Ohio, for more than 6,000 miles. The company also tested its braking and visibility. As for safety, Strick said that the cab was built like a NASCAR rollcage and featured a skeleton of half-inch solid steel.

Strick started advertising the Cab-Under as a truck that would pay for itself after only eight months of carrying additional cargo. The company even claimed that the truck was great for fuel efficiency–it was the 1970s, after all–because, in its eyes, eliminating the tractor up front was great for aero. I’m not so sure about that, but, either way, Strick claimed 7 mpg fuel economy.

The first bite of interest came from bubble wrap maker Sealed Air. The truck also got attention everywhere it went, as everyone wanted to know what the heck the truck was. Apparently, cops even pulled it over just to confirm that, yep, the rig was legal.

In May 1977, the Commercial Car Journal published a feature on the Cab-Under, where it described the rig in further detail. Technically, the magazine said, the trailer attached to the top of the Cab-Under wasn’t a trailer at all. Instead, it was a container with legs that allowed it to be lifted off the truck and left at a depot, and then lowered back onto a truck later on.

To load the container, the Cab-Under drives under the container. Then, air-operated fifth wheels raise to connect the container to the truck. The legs would then be stored away, and the container locked into place. When finished, the Cab-Under was technically a straight truck, as the cargo container was now one with the truck. From there, the driver hitched up an additional 27-foot trailer or 37-foot trailer, depending on which region they would be driving through.

A second Cab-Under was built in 1978, and this one had notable upgrades. Unlike the first example, this truck featured a full two-place day cab. Moving the radiator to the middle permitted Strick to add more cab space. Strick also added a second front axle, which allowed the truck to reach 84,000 pounds of total weight. Weirdly, Strick noted that if you bought a Cab-Under and fitted it with a Cummins V903, you would have to relocate the snail to get the engine to fit.

As interest grew in the Cab-Under, some asked about getting one as a fire truck or as a dump truck. Strick noted that it was a trailer builder and it wasn’t in the business of building trucks. The Cab-Under used off-the-shelf components and packaged them into a unique chassis, cab, controls, and container configuration. Thus, in Strick’s eye, the Cab-Under was always going to be a typical freight truck.

Tensions Rise

Unfortunately, not everyone was stoked about the Cab-Under. From Overdrive Magazine:

U.S. Sen. Ted Kennedy denounced the Cab-Under as unsafe. Future Public Citizen leader Joan Claybrook, then head of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, was not impressed when Strick brought the Cab-Under to Capitol Hill for a demonstration.

[…]

The Teamsters took the Cab-Under to the Transportation Research Institute at the University of Michigan, which confirmed everything Zubko knew to be true. “It was a stable vehicle,” Zubko says. “It couldn’t jackknife because there was no kingpin. In a rollover, the driver would be better off than in an articulated vehicle.”

The report also noted downsides. “An impact against a low, rigid barrier such as a retaining wall would be a problem, and in very bad weather, the splash and spray from the road surface would be a visibility problem,” Zubko says. “That was a valid criticism.”

Zubko didn’t really mention how much the Teamsters didn’t like the Cab-Under. I found the 1978 issue of Teamsters Magazine in question. In the issue, the magazine says:

In the area of safety and health, the board unanimously passed a resolution condemning the so-called “cab-under” tractor configuration now being developed by at least one manufacturer. The resolution, introduced by IBT Vice President and Central Conference of Teamsters Director Roy Williams, reaffirms the position of Teamster President Fitzsimmons that the “cab-under” configuration is unsafe. (A report on the “Cab-Under” configuration appeared in the August, 1977 issue of The International Teamster.) Fitzsimmons further instructed vice presidents to inform all Teamster Local Unions to notify their drivers that they should exercise all of their rights in Teamster contracts which protect them against driving unsafe equipment.

That’s not a positive start.

The Teamsters Magazine then published an entire report based on the findings of the aforementioned tests that it commissioned at the University of Michigan. The Teamsters held back no punches:

A STUDY commissioned by the Teamsters Union has confirmed what the union feared—the recently introduced “cab-under” truck tractor has serious design deficiencies which could endanger Teamsters Union members and their fellow motorists.

[…]

The cab-under poses “major safety deficiencies, especially in the areas of cab intrusion, down the road visibility and vehicle yaw sensing by the driver,” investigators concluded. The report also noted other problems that could arise. Cornering stiffness, upper vision limitations, glare and the reflection of the vehicle’s own lights in fog or mist, mirror exposure to damage and spray, and the startled reactions of other motorists—these were problems found inherent in the vehicle.

Potentially the most dangerous of the three major problems outlined, and the one of greatest concern to the Teamsters Union, is that of cab intrusion. That is the tendency of the front or side of the cab-under to give in in accident situations. HSRI arrived at conclusions in this area by devising various crash scenarios and evaluating how the cab-under would react, in comparison to other conventional designs. Among the situations hypothesized were a frontal collision with an equally massive and aggressive vehicle or obstacle such as another truck or large roadside object; a frontal or lateral collision with a passenger vehicle; a single-vehicle accident, such as a rollover or jackknife, and shifting loads. The study team found significant problems relating to protection of occupants in the current versions of the cab-under vehicle.

The report continues by claiming that the Cab-Under lacked adequate interior padding, that the interior had metal parts that could injure a trucker in a crash, that the headliner was inadequate for a crash, that the cab’s lap seat belt could injure the trucker in a crash, and that, in a terrible crash, the cargo container above might be able to impede on the cab.

The report didn’t stop there, as it claimed that since the cab rode low and was exposed, there was the possibility of the driver getting injured in crashes with cars, as well as incidents involving hitting road debris or animals. The report also expressed concern with cars crashing into the cab, as a car hitting a loaded truck is unlikely to make the truck budge much, but the cab could crumple.

Further, the report noted, the Cab-Under had upward visibility so poor that a driver of a Cab-Under that sat at a traffic light may not be able to see the traffic light itself. Other issues noted included the fact that glare from the headlights of oncoming cars could blind the driver and that, when the truck is driven in wet weather, its mirrors become useless due to water spray from the truck’s own wheels.

There’s even more that the report had problems with. Click here to read more of it. But in short, the Teamsters seemingly hated the Cab-Under. What’s interesting is how Strick interpreted the study compared to how the Teamsters did. Either way, the tensions between Strick, the Teamsters, and the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration did not help the situation.

The Cab-Under Fails To Launch

Still, Strick managed to keep interest and ended up leasing the second prototype to Wayne Daniels Truck in Mount Vernon, Missouri, and Red Ball Motor Freight in Dallas, Texas.

Ultimately, the Cab-Under would not go into production, and the reason why makes a ton of sense. Of course, there was the problem of getting truckers on board with the sports car of trucks, but, as Hemmings wrote in 2022, Strick might have accidentally killed its own market. As the publication notes, Jon Karel, vice president for national accounts for Strick Trailers, said that taking the Cab-Under to Capitol Hill likely helped to influence the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982, which finally did away with the harsh length limitations.

Thanks to that Act, there was really no reason for the Cab-Under to exist. Now, truckers could hook up big conventional tractors to long trailers. Apparently, the failure of the Cab-Under to launch didn’t matter a bunch to Strick, as after the Act’s passage, it now had a booming business in building bigger trailers, anyway. Besides, if the above is true, then the Cab-Under prototypes were still worth it as they helped get the trucking industry to the finish line in killing harsh length restrictions.

In the years since, Zubko held on to the first prototype, while the second was sold to a German company that used it to move flatbed building materials. Bucking Concepts would later take the truck and use it as a promotional vehicle until the company went bankrupt. The truck fell into disrepair, and, eventually, it was offered to Strick. The company wasn’t interested in getting the truck back, but Karel was, and in 2019, the second Cab-Under came back to America to undergo a full restoration.

As for Zubko, he passed in 2008 after amassing 46 years of engineering and tractor-trailer experience. His Cab-Under is now in the hands of private ownership.

The Cab-Under’s Legacy

The whole Cab-Under story is a fascinating one. Ronald Zubko’s truck was built to beat the system and to be a truck that carried the most cargo within the strict legal limits of the era. It’s fascinating to see what engineers can come up with when they have a mission that comes at odds with regulations.

What’s even wilder is the fact that the Cab-Under isn’t even close to being the only truck of the so-called “cab under” category. Germany’s Büssing built a cab-under truck in 1967. Likewise, the United States used a cab-under-style truck in the early 1960s to haul Minuteman missiles. Even older than those are Butler Brothers logging trucks of the 1950s, which are in a sort of similar cab-under configuration.

Perhaps the most famous cab-under truck in history is the Steinwinter Supercargo. Of course, it’s old, weird, and German, so of course, Jason Torchinsky has written about it:

That’s the Steinwinter Supercargo, a revolutionary new concept for a tractor-trailer truck design, shown first in 1983. Manfred Steinwinter was the eponymous engineer who came up with the concept, and while it seemed very futuristic and clever, it was actually quite flush with conceptual and design problems that prevented it from ever becoming anything more than a cool curiosity.

Unfortunately, history has not been kind to projects that have tried to turn large vehicles into sports cars. Pretty much every “driver’s RV” ever built has failed, and so did the sports car of semi trucks. It sounds like the Strick Cab-Under was great at hauling lots of cargo, and it looked really weird, but truckers really weren’t interested in any other part of it. Then, of course, the changing times and regulations meant that it technically became irrelevant before it even went into production.

Still, I keep finding myself blown away. Some impressive levels of thought and engineering went into this truck. Perhaps even more fascinating is that Strick wasn’t the only one to think that making a low-riding semi-truck was a good idea. But I guess it just goes to show that, when it comes to trying to make money, the trucking industry has always been willing to try out some truly wacky ideas.

(Topshot graphic: Strick Trailers)

Wow, never heard of these…they are insane looking! Talk about a “low rider” ha ha. Yeah, the great thing about regular semis is you’re up high so you can have as much forward vision as possible. Great article!

I highly recommend reading “The Box, How the Shipping Container Made the World Smaller and the World Economy Bigger”

Great idea except that you’d better not ever want to drive up (or down) a ramp or hill/incline of any kind greater than say… 2 degrees.

I grew up about a half mile from the Strick trailer plant in Fairless Hills, PA in the 70s. It’s still an industrial plant, Load Rite makes trailers in most of the area and they sub lease to other ventures. We saw the cab under a few times growing up, it would make the local newspaper when it was in town, and they would park it out front by the fence. It was really cool, space age looking. As a gearhead kid, it was like seeing something from a science fiction movie

Another problem with this is it takes up twice as much dock space as a single trailer pulled by a standard COE truck. Plus the container can’t even be moved around the freight yard without its special truck.

I think there should be a TRUE cab over sometime.

Imagine a truck that has a big square hole in the front. When loaded, a shipping container fits into the hole. Above the hole for the shipping container is the cab. The advantages are endless Off the top of my head.

Take that idea, but update it with modern technology!

Instead of having the cab attached to the chassis, make the entire cab into a giant drone. That way, the container is placed on the chassis, then the cab/drone flies up and lands on top. It then uses Bluetooth to control the chassis.

Any problems that arise can be solved with AI, or possibly Blockchain.

I shall name this design “Cabwarts.”

They will be driven by minors that have limited instructions on driving or teachers that are either absent minded or homicidal and care nothing for safety of the trainees.

I love stuff like this. Reminds me of the carriers that used to roll around cape Canaveral with vehicles on them

I remember reading about the Steinwinter way back when. It did look incredibly cool.

Before I got too far into this story I had to double check to make sure it wasn’t an elaborate hoax article. I’ve never seen anything like this. With my touch of claustrophobia, I would fight tooth and nail if someone tried to put me in that cab. Hats off to Mr. Zubko for trying.

Those two trailers Boeing uses with a cab mounted mid-trailer to help with steering are pretty cool. Would make for a fun story.

If you’re interested in more about how the shipping container made the world we live in possible, I highly recommend this book:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Box_(Levinson_book)?wprov=sfti1

Excellent book! Revealed a lot about dockworkers and how cargo was loaded in the ages before containers. Well worth picking up this book.

Agreed! Non-fiction well told is my favorite kind of book.

One of your last points is super interesting. It sounds like, unwittingly, Strick scared the industry into reforming. “Either standardize and relax these lengths, or be forced to drive this ‘weird-ass’ cabover thingy.”

I could see this coming back as autonomous truck solutions develop. No need for a cab even, just a sensor suite in the front and back. Add an electric drivetrain and now it can move in either direction as fast as it’s able. Drive straight up to a dock, unload, and head back to the docks or a charging station.

Check out Parallel Systems which is having some success doing this for rail cars. Basically making the cars self-organizing.

Without the box on top, it looks like something from Mass Effect.

Check out the Long Load Steer Car used by Boeing to transport aircraft parts. It’s a combo of this thing and a hook-and-ladder firetruck setup.

I came here to say the same thing as I’ve driven by them many times over the years. Definitely would be interesting to be in the rear.

I see an additional, practical reason big rig guys hated this. Imagine navigating a complicated parking lot or port facility with none of the height to see over… anything, even dock personnel?

Put a camera on top of the trailer and a display in the cab. Problem solved.

That wasn’t a trivial thing to install in a vehicle back in the Seventies.

Safety standards were nowhere near as stringent as they are today so I think an off the shelf B&W security camera and TV would have done the job just fine.

If not then maybe a periscope.

You weren’t around in the Seventies? I was but I wasn’t tracking the tech, so I asked AI- “While security cameras existed for military and commercial use as early as the 1940s, cheap, low-voltage cameras became widely available for consumers in the late 1990s and 2000s. This shift was driven by two key technological advancements: the transition from analog to digital video and the growth of internet access in homes.

Timeline of cost reduction and accessibility

I was around in the 1970s but I wasn’t old enough to be involved with security systems.

To your point though. Were motorized, multi camera systems with zoom, motorized focus, and recording capability along with an array of largish monitors to try to eke out subtle movements like card manipulation or pickpockets expensive? Probably. Especially if they also required color or night vision (e.g. near infrared)

This isn’t a bank or casino though. This application just calls for a single, non motorized, fixed focus, visible spectrum camera with a single cheap 9″ or so B&W monitor and no recording capability.

Or a periscope.

The only problem I see with that is that the truck was designed to detach from the container and drive away. So, to make this work, every container would need to have a camera and presumably some sort of quick-disconnect cable. 🙂

Depends how it was designed I suppose.

They could have just used early wi-fi, right? ; >

And it gave us the *other* truck concept in the OMG that’s 80s scifi show The Highwayman.

The ideas about the design being worse in a collision with normal cars irritated me for a moment, because the norm is that large trucks’ advantages in a crash are at the expense of those smaller vehicles.

Then I realized the issue, none of those normal-height passenger compartments have literal tons of cargo above and behind them to act as a momentum-hammer ensuring they’re crushed between it and whatever they’re colliding with. Yikes.

Which is worse – Being crushed from above, ahead, or behind?

Yes

Por que no los dos?

“the norm is that large trucks’ advantages in a crash are at the expense of those smaller vehicles”

Yet another reason to get an Altima:

https://www.motorbiscuit.com/woman-receives-minor-injuries-when-semi-truck-flattens-her-altima/

From a truck driver point of View, I would argue this setup is safer. Take a normal truck and run it into something at speed. The load will attempt to go through the back of the cab and become a problem.

With this, the load just flies off the truck and becomes a problem for whatever he hit.

Sort of like those EV designs that fire the battery out of the side so the fire isn’t their problem any more. only with a fully loaded shipping container.

I can see what you’re thinking, but if the cargo doesn’t have the momentum or room to travel beyond the length of the vehicle, it’s gonna be left sitting on top of the impact-compromised cockpit.

Just don’t tighten the straps and let it fly.

Sometimes trucks crash into functionally-immovable structures/geology, and the “cargo container that’s safer (for the driver) to eject forwards by putting it behind a giant drill” is a different product entirely.

This was a side-effect of Maserati ownership, because when you own a Maserati questionable decisions become normal.

If the truck rear-ends someone, would the trucker volunteer to be the Mansfield bar?

I like the natural evolution of this with Hyundai’s concept for autonomous tractors:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d1KhBwtxYbA

If you’ve seen “Logan,” it looks very similar to the autonomous tractor trailers there.

I’ve seen “Logan’s Run” – but no trucks….

Imagine restoring one of these to be a true track day beast.

So the teamster’s issue with the cab-under was that it was only as safe as… every single other passenger vehicle on the road?

I’m pretty skeptical of statements from the Teamsters, but I have to think they probably also really wanted the overall length requirements removed, too. Seems this worked out for everyone involved.

I am glad someone else also read that and thought “what a crock of $hit!” Ohhh these poor truck drivers with headlights from other vehicles impacting them GTFOH!!

Every single other passenger vehicle on the road with several tons of weight directly above and behind them, yes.

The tire spray and low headlights thing got me. It doesn’t look much shorter than a sports car of the era and they managed.

I thought that at first read as well. But how many miles do these guys and gals put on the road compared to you and me? Driving a low slung vehicle at night in the rain can be quite stressful. Then add in actually having to be somewhere on time and within safe operating time windows and your family’s next meal depending on you getting this done. Day after day. So I think we can cut them a little slack and maybe make their job a little less stressful and a little more safe when we can.

I saw one of these once driving through the Shenandoah Valley in Virginia in the mid eighties, hauling large underground tanks on top.

I got a chance to talk to the driver and he seemed to like it.

Since I have no sense of self-preservation and like driving cab over/under/whatever vehicles,

daily

Just curious, was wondering when your next article will be? I really enjoyed reading about your wrenching adventures!