A train crash is usually a serious event, one where property damage, injuries, and even fatalities can reach depressing levels. Usually, everyone avoids trying to crash trains whenever possible. Yet, for decades spanning the 1800s and early 1900s, Americans nationwide sometimes got their kicks by intentionally crashing trains into each other, and then running toward the wrecks. Let’s look into the events that got so huge that tens of thousands of people gathered to watch trains crash and, sometimes, blow up in spectacular fashion.

I’ve been finding myself enamored with early American vehicle history. The dawn of rail, river, and road transportation is fascinating. At first, trains, steamboats, and early automobiles were world-changing inventions that permitted mobility that had never been seen before. What’s amusing is that it didn’t take long for operators of these vehicles to start doing shenanigans with them.

I recently wrote about how Americans started building practical steamboats in the 1800s, and then started racing them almost immediately after. Steamboats captured the hearts of people from sea to shining sea, and nobody seemed to care that these races were often shockingly deadly. But this wasn’t the only way Americans would pass time. If we weren’t racing boats at the breakneck speeds of 13 mph, we were disposing of locomotives by ramming them into each other.

America Was A Leader In Steam Trains

The history of steam locomotives draws some parallels to the development of steamboats. In the earliest days of rail-based transport, wagons rode on wooden and then metal rails, and those early forms of trains were moved along through muscle power or pulled by cables.

In 1712, English inventor Thomas Newcomen invented an atmospheric engine. Scottish inventor James Watt then took Newcomen’s design and, in 1765, turned it into the practical steam engine. Various inventors throughout history would take these engines to move the world.

Some of the first steam locomotive designs were made and even tested in the 1780s in America and Europe. Here in America, a major locomotive pioneer was John Fitch. If that name sounds familiar, it’s because I very briefly mentioned Fitch’s name in my steamboat piece. In 1787, Fitch fitted a Watt engine to a boat, the Perseverance, and demonstrated it to delegates from the Constitutional Convention. Fitch would go down in history for creating America’s first steamboat service, but before that, he loaded steam into trains. From the National Park Service:

John Fitch invented the steam railroad locomotive during the 1780s and demonstrated his little working model of it before President George Washington and his cabinet in Philadelphia. His idea was to use a full-scale version of his little engine to haul wagons–freight cars, actually–across the Allegheny Mountains where the United States faced an almost insuperable problem of supplying, through a nearly roadless wilderness, Major General Arthur St. Clair’s campaign against hostile British-supplied Indians of the Old Northwest.

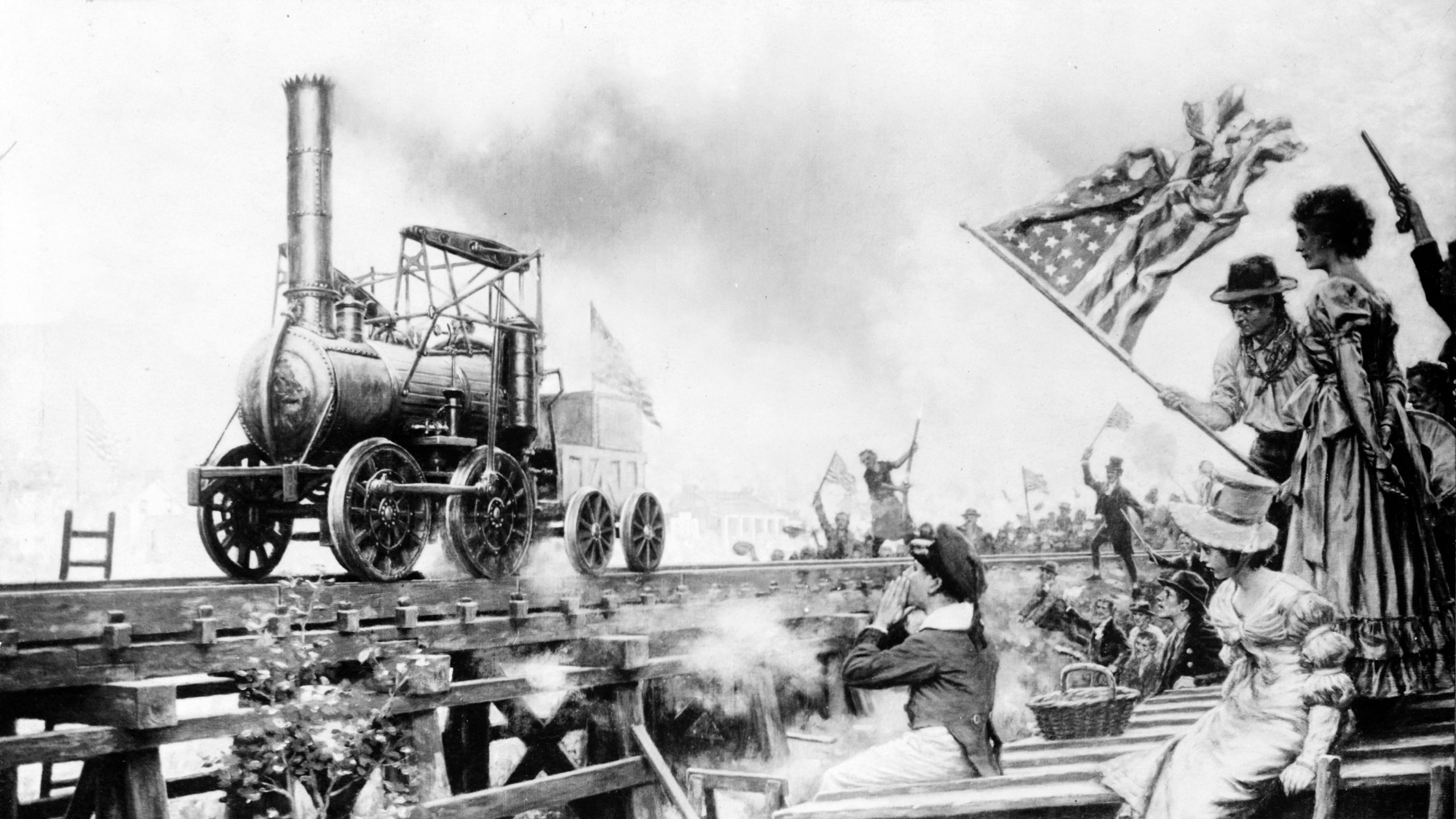

America was at the forefront of steam locomotive development, and, depending on who you ask, America invented the steam train locomotive, not Britain. Still, even if America invented the locomotive, America would be slow to adopt the technology. The first full-size locomotive to go into service in America was the Stourbridge Lion (above), which was imported from England and run in Pennsylvania in 1829.

America’s lust for trains would explode nearly immediately after. The first successful American locomotive, the Tom Thumb, was built in 1830. Trains would captivate America so much that rails would soon criss-cross the entire country, and the Transcontinental Railroad would be completed on May 10, 1869.

You probably won’t be surprised to read that, just like with steamboats, America also loved to race trains whenever possible. Railroads competed with each other to see which was faster by blasting between two destinations. But racing trains apparently didn’t rise to the level of popularity of racing steamboats. Instead, trains would find their claim to fame in spectacular wrecks.

Crashing Trains For Fun

It’s not known who was the first person to crash a train for fun, or when it happened. However, most sources suggest that the practice rose to popularity in the mid-1890s.

One of the first examples of these crashes was orchestrated by A.L. Streeter, no known relation to me [Ed note: It sounds like someone related to Mercedes, just based on what you’re about to read. -MH]. As the Akron Beacon Journal writes, Streeter, then a railroad equipment salesman from Illinois and a conductor for the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad in the past, cooked up the idea to crash trains as a way to make money.

According to an 1896 issue of The National Magazine, Streeter wanted to conduct this crash in Illinois as early as 1892, but railways weren’t exactly lining up to crash their trains for fun. But he did get interest from the Cleveland, Canton & Southern Railroad, which was running out of cash and thought that crashing trains could bring some business. It wasn’t even that hard for the railroad to help Streeter out, as it had a pair of rusty retired locomotives that it was able to bring back to life just long enough to crash into each other.

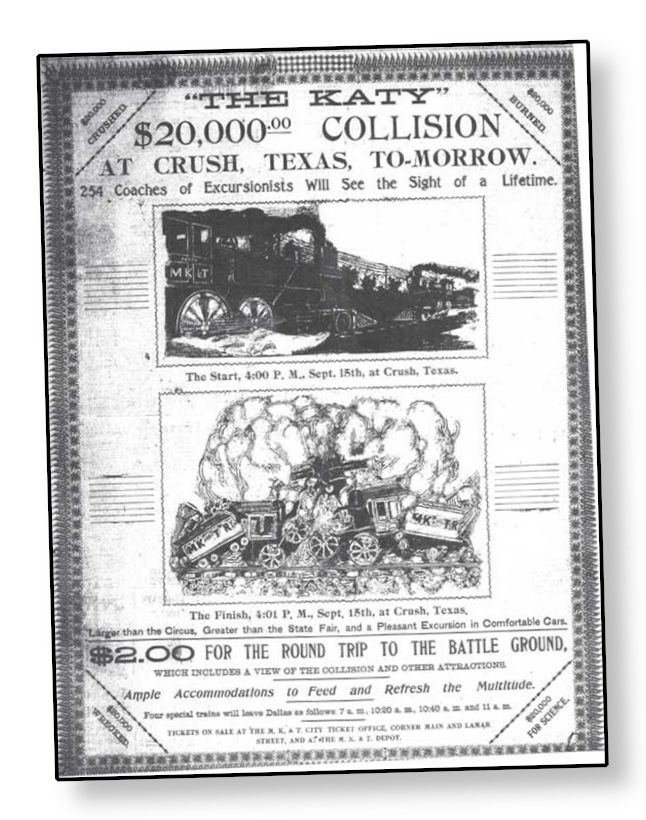

For his part, Streeter turned into a bit of a showman. He marketed the July 20, 1895, crash, which would take place a couple of miles outside of Canton, as being the most wonderful exhibition in America. From the Akron Beacon Journal:

“Two monster locomotives, with full head of steam, starting a mile apart, will rush toward each other at the rate of 60 or 70 miles an hour, and allowed to come together with a crash that will result in the most horrible HEAD-ON COLLISION ever seen or heard of,” Streeter advertised in the Akron Beacon and Republican and other Northeast Ohio newspapers.

“It will enable those present to note the terrible effects of a railroad horror. It will take place in an enclosure, and the public will be free from all danger. Everybody should see this exhibition.”

The pair of locomotives was painted red, white, and blue. One locomotive was named the Free Trade for the event, and the other was the Protection. These trains would symbolize the collision of two economic theories. Each train would also be loaded up to 40 tons by hauling flatcars carrying rocks and decorations.

Streeter charged 75 cents per person to watch the train crash, and the railroad dropped people off at the site for 15 cents a ride. The organizers were hoping for a crowd of 20,000 paying at the gate. Thousands of people did arrive, but most of them found free vantage points near the crash and avoided paying the 75-cent fee. Only about 200 people paid to watch the crash.

The plan called for the locomotive crews to back the trains up about a mile, engage full forward thrust, and then jump out. The uncontrolled trains would then meet and crumple at whatever speeds they managed to attain. Unfortunately, the plans went off the rails when, as the trains approached, the crowd rushed into the projected point of impact. Had the crash continued as planned, there would have certainly been deaths or injuries. Streeter canceled the crash.

The aftermath was a disaster. Few people got refunds, and countless were mad that they paid to see the supposedly best event ever and got nothing. Apparently, Streeter didn’t even pay the $2,400 fee for permission to run the event. Streeter himself lost $800 in the ordeal. Sadly, I could not find an accurate inflation calculator that goes this far back.

However, Streeter learned that there was clearly a lot of interest in crashing trains, so he tried it again on Memorial Day 1896. That time, at Buckeye Park in Ohio, locomotives A.L. Streeter and W.H. Fisher (named after a Columbus, Hocking & Toledo Railroad official) crashed in front of a crowd of 25,000 people.

This time, Streeter placed dummies in the trains that were dressed like engineers, which added even more flair to the crash. The two trains collided at roughly 40 mph and were nearly totally destroyed in the collision. Train parts went flying in every direction. The crowd, who each paid a couple of dollars to be there, cheered through the shrapnel flying through the air. The train crash was such a smashing success that it became national news, and one paper wrote, per the Smithsonian Magazine: “the most realistic and expensive spectacle ever produced for the amusement of an American audience.”

Streeter’s success in this event was apparently infectious, as at least six more staged crashes were scheduled in the year after. Some organizers hired Streeter; others just copied his idea. It was only that same year that perhaps the most infamous staged train crash in history happened.

Building A Fake Town To Crash Trains

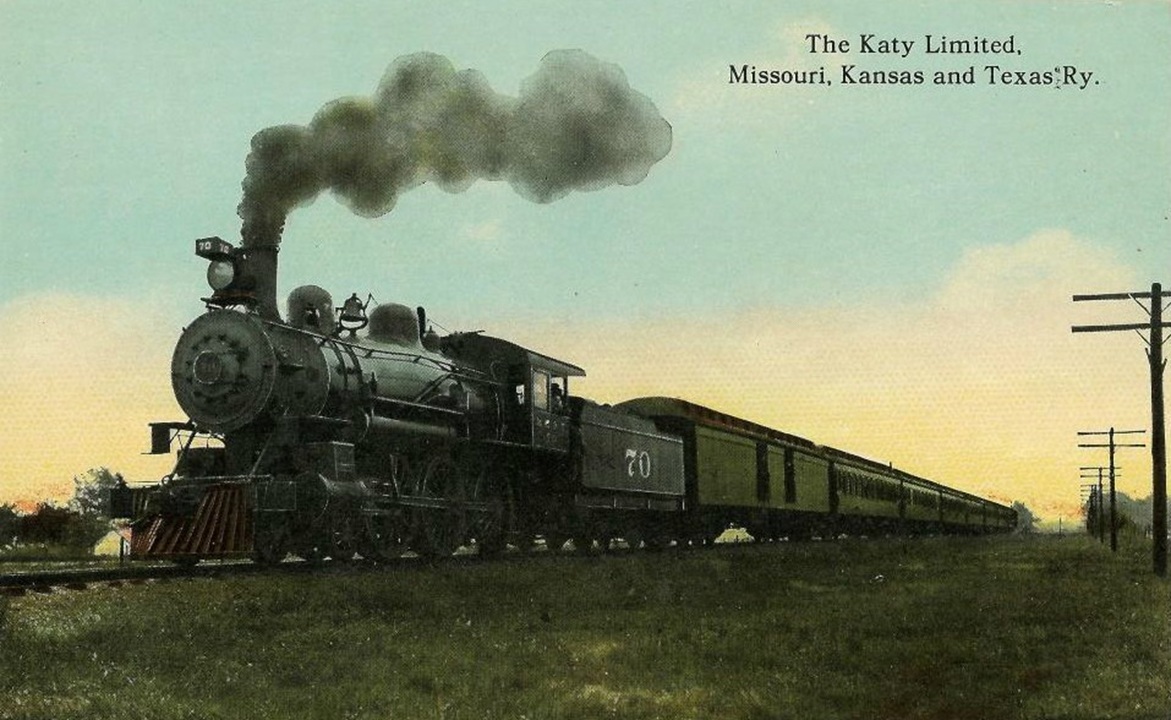

William George Crush was the general passenger agent of the Missouri–Kansas–Texas Railroad, which was known as the Katy. The railroad snaked its way through its namesake states, and as it upgraded its equipment in the late 1800s, it had a bunch of older, outdated locomotives sitting around and doing nothing. Crush, perhaps motivated by the success of Streeter, decided to promote the railroad by organizing his own train crash. But his would be bigger, better, and more bombastic than anything Streeter had done by that point.

Katy railroad officials loved the idea and gave it the green light. As the Smithsonian Magazine writes, the officials had a good motivation to rubber-stamp the plan. A quarter of America’s railroads were wiped out during the depression of 1893. The Katy survived and managed to rake in $1.2 million in passenger tickets and $3 million in freight in 1895, but the company wanted to secure its position even further.

Crush’s plan was grand. He planned the event over a year in advance. Technically, Crush’s plans actually predated Streeter’s successful crash. The railroad chose two outdated 35-ton 4-4-0s that were built in 1870, and took them on a promotional tour. No. 999 was painted green with red accents, and No. 1001 was red with green accents. The trains, which hauled seven cars decorated in advertising from sponsors, toured the Katy’s trackage, handing out leaflets at every stop. This marketing campaign was brilliant, as it meant that, in short order, the news traveled nationwide. Sponsors included P.T. Barnum’s circus and the Orient Hotel.

Another clever part of the marketing was that spectators would not be charged to view the train crash, and the railroad offered discounted rates to get them there. As a result, people would come to see the crash from as far as New York City.

The Katy’s preparations for the crash were surprisingly complex. While Streeter crashed trains on existing tracks, the Katy and Crush would go to insane lengths to ensure a successful event.

The railroad did not use existing trackage for the run. Instead, as Trains.com writes, the railroad’s track crews of 500 men laid a spur off of the Katy’s trackage in Waco, Texas. Then, four more miles of rails were laid. This ensured that the crash wouldn’t happen near existing tracks or towns. Since the crash was taking place in the literal middle of nowhere, the railroad had to build a depot, a 2,100-foot platform, a shop, and two telegraph stations. In other words, the railroad built an entire temporary town, and named it Crush, after the event’s mastermind.

The prep continued from there, from Trains.com:

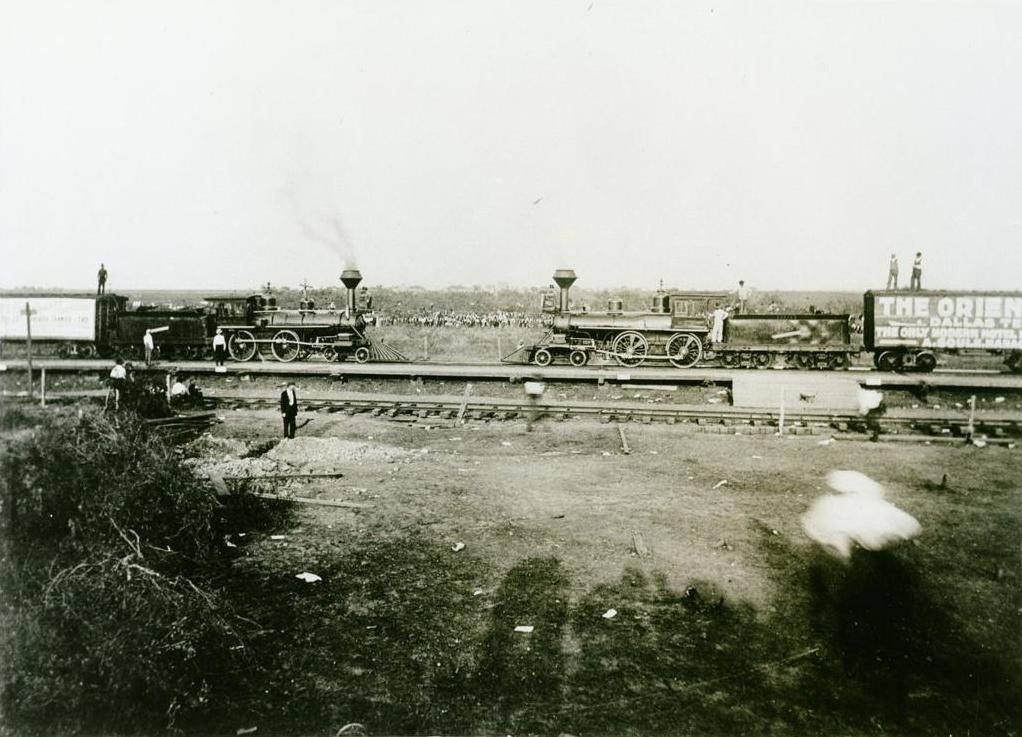

For weeks, crews ran the engines up and down the 4 miles of track to see where the exact point of impact would be. From the place they decided on, workers built a grandstand 200 yards away for VIPs, and a press box 100 yards away for photographers. Among the photographers was an assistant to Thomas Edison, who was filming events around the country with his new motion picture camera to show on his vitascope screens. Additionally, there was a bandstand, and three stands for politicians to entertain the crowds with oratory.

William Crush arranged to borrow a tent from the Bailey circus, and the superintendent of the Katy eating house service was put in charge of sandwiches to be sold there. To keep the crowds in good shape, he arranged for eight tank cars full of free water and ice for the public. In fact, the whole event was free. The only cost was the tickets to get there: a $2 round trip for Texas residents.

Medicine shows, gaming stands, lemonade stands, and soda stands were allowed in the carnival setting. Liquor was not sold, as promoters anticipated that everyone would bring their own. A jail was set up in case of problems.

As an archived issue of the Katy’s employee magazine claims, Crush went to great lengths to try to ensure the event’s safety. When the two trains rolled into the fake town, track crews removed the track behind them. This ensured that, if either train somehow continued for any reason, there would not be an out-of-control train speeding into populated areas or onto the Katy’s mainline.

Crush, unlike Streeter, also did not use worn-out locomotives. While the 4-4-0s chosen by the Katy were old and outdated, the railroad made sure they were in perfect mechanical condition for the event. The idea here was to ensure no explosions or anything that would either stop the crash or injure spectators. The trains even had extra safety chains to make sure they did not violently separate from their tenders and cars during the crash event.

The Katy then had skilled crews running and maintaining the event’s engines. Frank Barnes and E. Stanton operated the No. 999, and Charles Cain and S.W. Dickerson were on the No. 1001. The engineers assured the public that they were going to crash the trains at a speed that wasn’t fast enough to blow the locomotives’ boilers.

America’s Infamous Staged Train Crash

The day of the crash was September 15, 1896, and it was a total blowout. Some 40,000 to 50,000 people had arrived in Crush. Most of them arrived in the 33-plus trains to the event, which dropped people off every 12 minutes. If you rode to the site from anywhere in Texas on Katy’s line, your ticket was just $2.

Eventually, the crowd was in place and backed away from the tracks while the stage was set. The trains met at the expected impact point and then reversed a mile out. Then, their respective crews set the trains to full speed ahead and jumped out.

The trains met at their intended collision point, but what happened next was very unexpected, from the Texas State Historical Association:

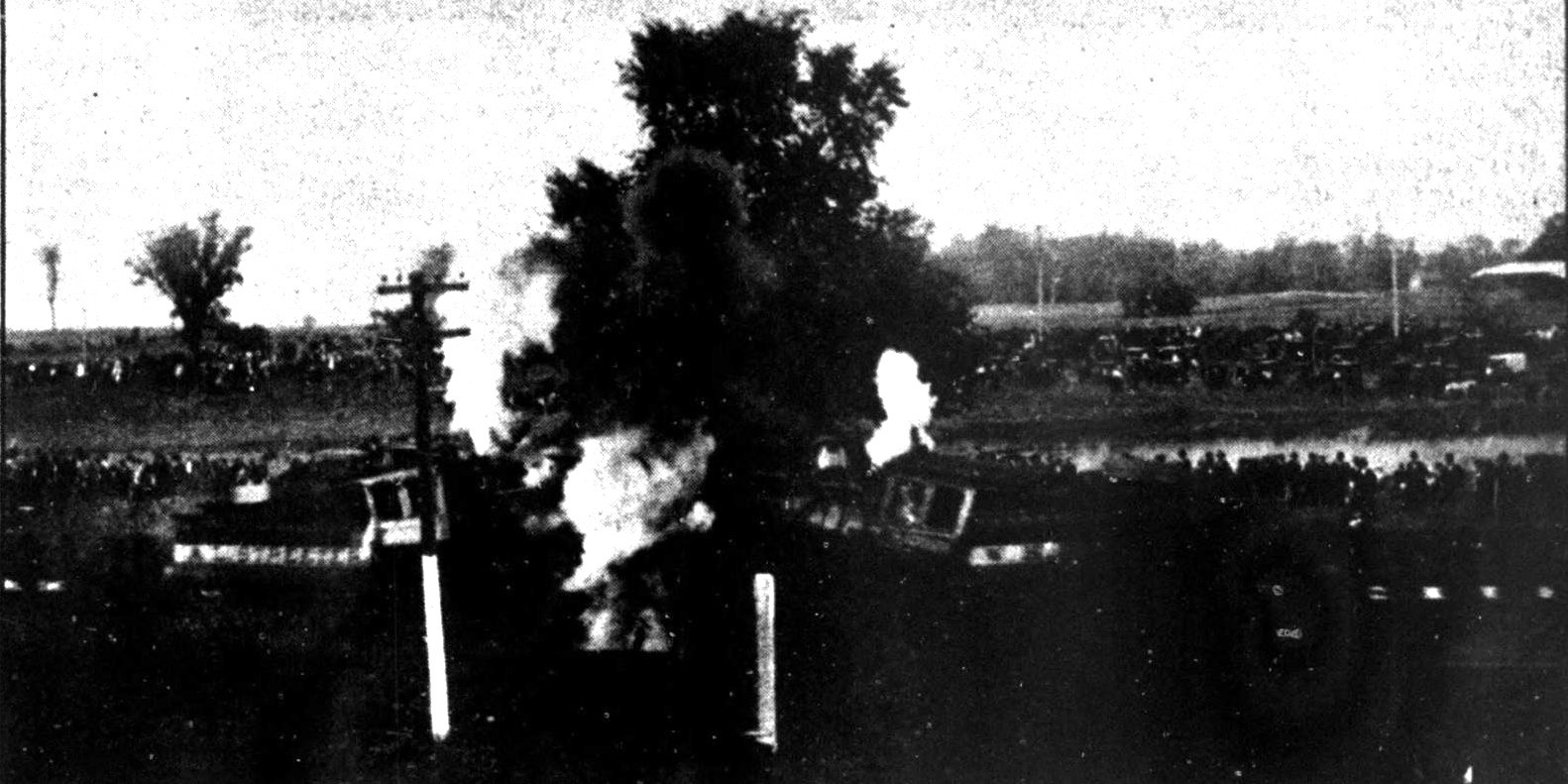

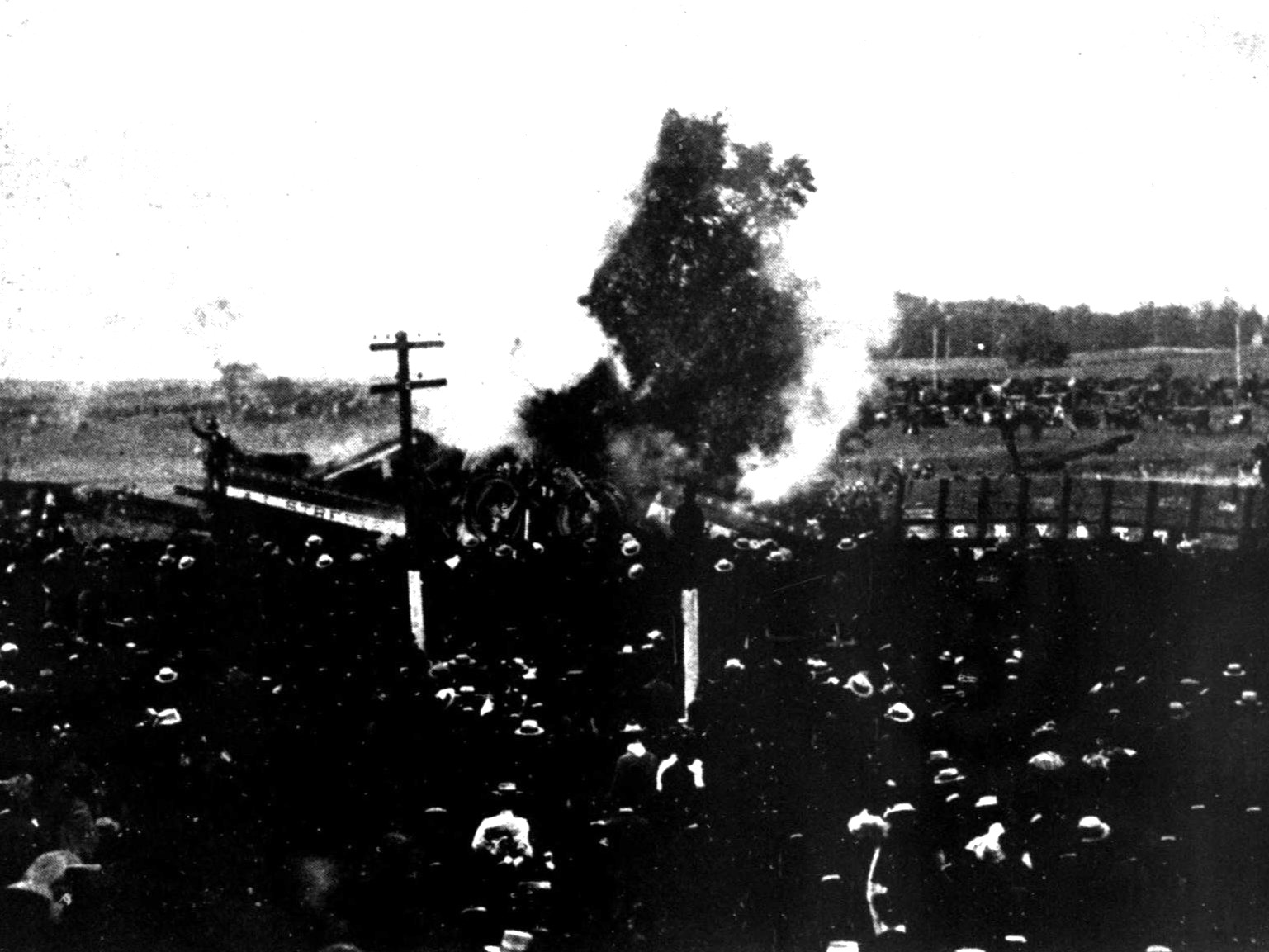

A great cheer went up from the crowd as they pressed forward for a better view. The locomotives jumped forward, and with whistles shrieking roared toward each other. Then, in a thunderous, grinding crash, the trains collided. The two locomotives rose up at their meeting and erupted in steam and smoke. Almost simultaneously, both boilers exploded, filling the air with pieces of flying metal. Spectators turned and ran in blind panic. Two young men and a woman were killed. At least six other people were injured seriously by the flying debris.

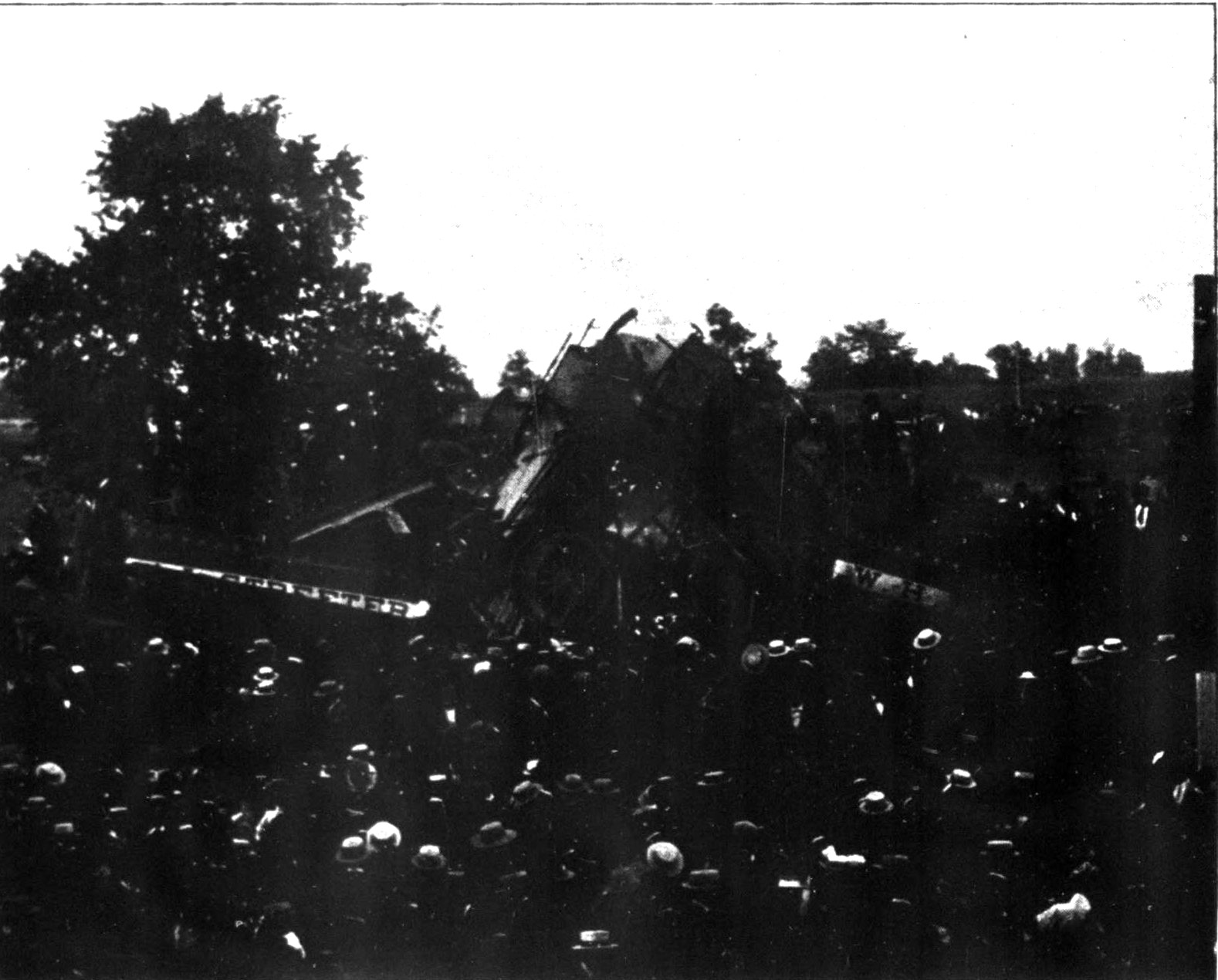

The Katy wrecker-trains moved in to remove the larger wreckage, and souvenir hunters carried off the rest. People began to leave for home, the tents, stands, and midway booths came down, and by nightfall Crush, Texas, ceased to exist. The Katy quickly settled all damage claims brought against it with cash and lifetime rail passes. As for George Crush, the railroad fired him that evening but relented and rehired him the next day. He continued to work for the Katy until his retirement. Composer Scott Joplin commemorated the event in his march Great Crush Collision which was published just a few weeks after the wreck. It has been surmised that the spectacle drew its huge audience in part because it occurred at a time of economic distress when railroads symbolized to many the evils of the big business “octopus” and were a target of attack for populist politicians.

Period reports described chaos on apocalyptic proportions. One reporter said, via the Smithsonian Magazine:

“A crash, sound of timbers rent and torn, and then a shower of splinters. There was just a swift instant of silence, and then, as if controlled by a single impulse, both boilers exploded simultaneously and the air was filled with flying missiles of iron and steel varying in size from a postage stamp to half a driving wheel, falling indiscriminately on the just and unjust, the rich and the poor, the great and the small.”

One report said that an entire driving wheel from one of the trains was blown 2,500 feet by the explosions.

If you’re not abreast of your steam trains, a driving wheel is one of the gigantic and heavy metal wheels that provide traction for the locomotive. To send one of these flying nearly a half mile means some incredible energy was released in the boiler explosions. Jervice C. Deane, the official event photographer who took the photos that are included here, lost an eye due to a steel bolt fired from one of the blown-up locomotives.

Amazingly, all of the death and injuries didn’t dissuade other showmen from following the lead set by Crush and Streeter. The Katy even got international attention from the event.

The Crashes Continued

Since this activity went on for so long, there are even videos, like the one above, of trains crashing!

Carnival barker and theatrical manager Joseph S Connolly made an entire career out of crashing trains. According to the Guinness Book of World Records, between September 1896 and August 1932, Connolly staged approximately 73 train crashes for public exhibition. His knack for crashing trains gave him the nickname “Head-on Joe.” His crashes were even bigger and more explosive than the Crush’s, even though the “Crash at Crush” is perhaps the most infamous exhibition train crash in history. From the Guinness Book of World Records:

Joe Connolly’s first deliberate train-wrecking took place in Des Moines, Iowa, on 9 September 1896. It established the basic premise he would use for all his future events, which was more safety conscious (given late-19th century standards of what constituted “safety”) than those of his rivals. A length of track was laid down adjacent to the grounds of the Iowa State Fair and two near-obsolete locomotives were acquired from the local railroad company. The crowds were charged 50 cents to enter the viewing area, but were kept in a fenced off area a “safe” distance from the tracks. Railroad engineers backed their locomotives up to the farthest extent of the track, built up the steam pressure and then set them in motion, jumping clear as they picked up speed.

The Iowa train-wrecking drew around 20,000 paying customers, and boosted attendance to the state fair considerably (between 50,000 and 70,000 attended the fair that day). It cost a reported $8,500 to stage the wreck (around $260,000, adjusted for inflation to 2020), but netted more than $10,000 (c.$310,000) in direct gate receipts. Connolly was paid $3,558 (c.$110,000) for his work.

Here’s another video of trains crashing:

Amazingly, over the course of nearly 40 years, Connolly would manage to crash a total of 146 locomotives. Now, nearly a century later, he still holds the record for the most trains crashed. Reportedly, Connolly found ways to spice up his crashes. Sometimes, he’d paint the locomotives with the names of political candidates, or intentionally rig them to blow using dynamite or gasoline.

According to the book, The Man Who Wrecked 146 Locomotives by James J. Reisdorff, staged train wrecks remained popular until the 1930s. The Great Depression changed America’s outlook on crashing trains for fun. Suddenly, crashing sometimes perfectly good trains was seen as wasteful, and the events lost popularity. Connolly’s last staged wreck happened at the Iowa State Fair in 1932. After the trains crashed, he walked away and retired from crashing trains. As Atlas Obscura writes, one of the last staged train crashes for the public was likely in 1935.

A Product Of The Past

Today, the idea of crashing trains just for the fun of it sounds absurd. Sure, we see trains crashing in movies all of the time, but there isn’t exactly anyone lining up to ram two diesel-electric locomotives together. Certainly, such a thing would be seen as too dangerous and too wasteful today. An operational locomotive can pull freight, pull passengers, or be parted out. Today’s locomotives also carry thousands of gallons of diesel each.

But for a period of around four decades, intentionally crashing trains wasn’t seen as just fun, but good for business, too. If you were a cash-strapped railroad, sending two locomotives into each other was seen as a viable marketing strategy, and it was largely thanks to the likes of Streeter, Crush, and Connolly.

This is just another fascinating artifact from American history. Americans used to enjoy some of the weirdest pastimes despite the fact that just spectating in them could have led to death or dismemberment. A part of me wonders what it must have been like to live during such a time. Would you be willing to stand by a track as two roaring steamers crashed?

Top photo: YouTube/Public Domain

They were desperate for diversion.

I know many were older trains and such, but it’s still surprising this was somehow profitable. I guess labor was cheap!

I mean, Whistlin’ Diesel exists, he’s basically the same thing.

People get bored easily. Stuff happens.

As a three or so month old baby, I slept through the derailment of a steam engine and of some of the following cars two or three blocks from where we were living. I can’t imagine the sound that made. And I also can’t remember it. My parents didn’t hear it either, but my dad was a volunteer fireman at the time and heard the sirens and volunteered his services.

I can’t imagine any railroad company intentionally sending even retired diesel-electric locomotives into each other, now. It would probably just make a lot of noise and maybe mess up some tracks.

Welcome to the United States of America where we like to:

I lived in Cleveland for two and a half years and it wasn’t as bad as you might think. I actually enjoyed all the ethnic neighborhoods and the opportunities to have their cuisines. Minus 20 degrees F was interesting, but it was sunny and dead calm.

Minus 20 F in a blizzard in Winnipeg was a lot worse. And I still like Winnepeg.

The Chik-Fil-A thing is more Texan than Ohio-ish.

Electing horrible politicians is global.

I’ve been married to a human woman from Ohio for over 26 Earth years. I have a love/hate relationship with that state.

I get that. None of my marriages have lasted 26 years. So congrats. The ends have always been painful. And sometimes expensive.

And I’m a beige resident/citizen in a grey sedan. Always liked your username. I would be an expat, but my 89-year-old mother is still alive. And I won’t leave the country until she does. 🙂

I was blessed and we lasted till the end of her life here. 38+ years.

Sorry for your pain though.

My Mom died in 1997.

Word is she is still looking into ways to move to Canada…

I’m a quarter Canadian. But I don’t know if that’s enough to get a CN passport. And wow, real estate in BC is expensive!

Not only all of the above, yet the Supreme Court is currently trying to decide if weed users should be allowed own a gun…

America. WTF happened to you?

How else are you supposed to protect your crops then?

We used to be able to just do shit.

For anyone who wants to see a steam-train in action, the Golden Spike National Historic Park at Promontory Point, Utah runs their two trains most afternoons in the summer. It is really fun and even a little educational.

I am suddenly am reminded of Farmer Brown’s bad day…

https://www.reddit.com/r/calvinandhobbes/comments/1d937zq/farmer_browns_bad_day/#lightbox

My all-time favorite Calvin and Hobbes! My boss actually ordered a custom print to hang in our office of that after I showed it to him.

Second place goes to Tyrannosaurs in F-14s.

Calvin and Hobbes!

It never gets old!!

I was partial to the deadly tornado myself!!

SO MUCH YES!!

Wow! What a cool article!

Thank you for this.

hats off to Sparrky for his take, I aplaud

Thanks for noticing!

“For weeks, crews ran the engines up and down the 4 miles of track to see where the exact point of impact would be.”

Reminds me of my high school maths word problems. I much prefer this empirical approach

Reminds me of how Calvin’s dad explained bridge load ratings.

So the question then becomes “how long would it take for clean up workers from two different cities to arrive at the crash scene?”

Be sure and show your work, or you will only get 1/2 credit on your answer….

Being an Iowa native, I’ve gotten to hear my Grandpa talk about my Great-Grandpa’s stories of seeing this happen in person at the Iowa State Fair. It did sound like quite a spectacle!

This was often bundled in with the stories of my Great-Grandma being one of the early great-depression era townsfolk that would always cook a meal for any passing hobos, but they would have to wait for it out side of the alley-gate.

Great-Grandpa was also apparently a boot-legger, but that involved a milk truck, not a railroad.

I sometimes wish I could have set up a tape-recorder every time we went to the grandparents’ place years ago.

I wish more people would do that. Once those people are gone, so are their stories.

I have an extremely old VCR tape with my Grandpa talking about the old days for a couple of hours.

He passed in 1990 at age 88.

He saw a lot of shit go down in 88 years…

From the Wright Brothers to the Moon Landing and a lot more…

“…A.L. Streeter, no known relation to me…”

“…Streeter, then a railroad equipment salesman from Illinois and a conductor for the Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railroad in the past,…”

The “relation” between Mercedes and A.L. may not be known, but it sure as hell exists.