Back in the 1970s and the 1980s, Japan went through a very short obsession with turbocharged motorcycles. The promise of the boosted bike was hard to ignore; by using a turbocharger, you could build a smaller and lighter motorcycle that had the power of a bigger bike. In theory, these motorcycles were supposed to be the best of both worlds, but in practice, they were unruly, violent, and hopelessly complicated. In 1983, Suzuki engineers created what it thought would be the ultimate boosted motorcycle, one that offered the benefits of turbocharging without excessive lag or scary power delivery, with its XN85 Turbo. They succeeded–though the bike was not a sales success. It was such a weirdo that the turbo wasn’t even the best part, but its handling.

As I wrote in the last entry in this series on Japan’s wild turbo bikes of decades ago, the nation’s first “production” turbo motorcycle was the 1978 Kawasaki Z1-R TC. This bike, which started life as a Kawasaki Z1-R before getting boosted by the Turbo Cycle Corporation, was such an unruly ride that buyers allegedly had to sign liability waivers. Ultimately, the Z1-R TC was too unreliable, too unpredictable, and too expensive for most casual riders to bother.

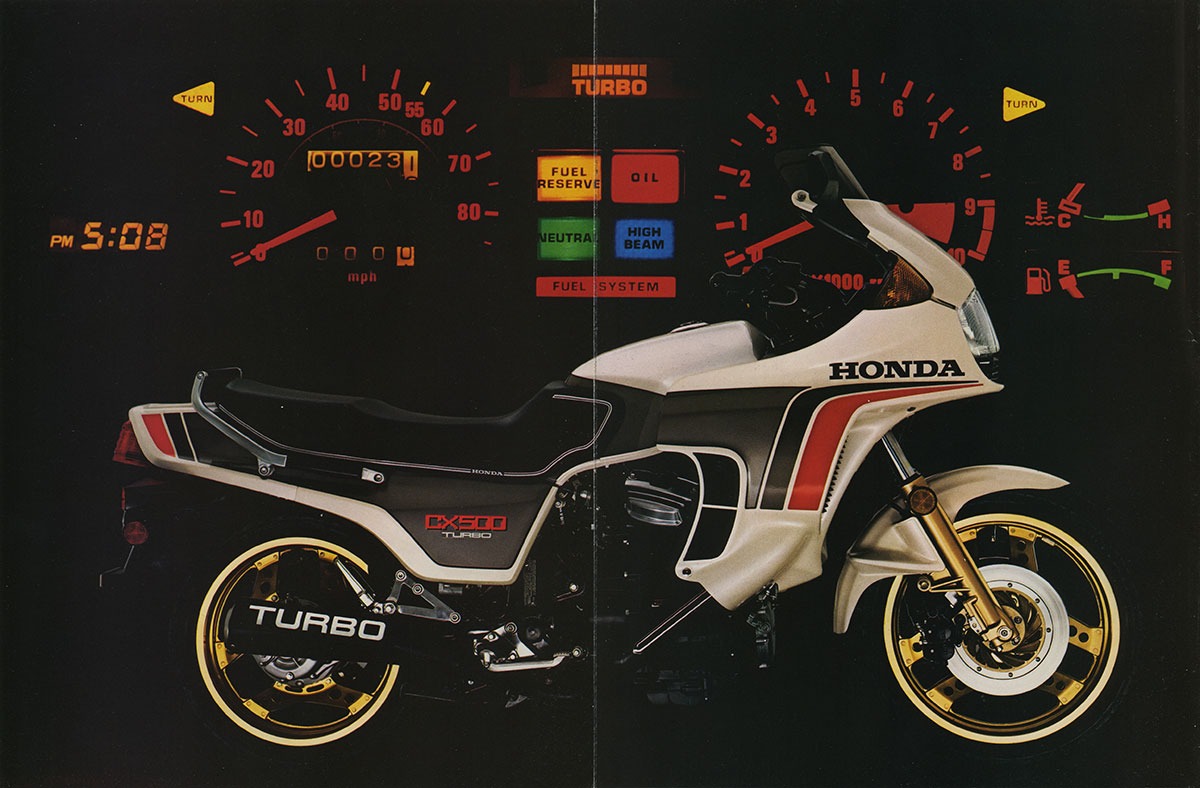

By 1982, the first mass-produced turbo motorcycle, the Honda CX500 Turbo, hit the scene. Unlike the Kawasaki, the Honda was designed and built by Honda, and Honda’s engineers took an obsessive approach to making the idea of a turbo bike work. They kept weight down, worked with a supplier to create a proper motorcycle engine turbo, and controlled the beast with what was then a state-of-the-art computerized fuel injection system.

Honda’s bike was reliable and didn’t blow up if you looked at it the wrong way. The bike was also controllable once the boost kicked in. Yet, not even Honda’s brilliant engineering for the era could beat the quirks of a turbocharged bike. The CX500 was known for its laggy turbo, heavy weight, poor fuel economy, and pricing that made it more expensive than a liter bike. Riders wanted bikes that rolled into and out of corners smoothly, not ones that surprised them when the boost kicked in.

One of the fabulous parts about the Japanese motorcycle industry is that the Japanese big four – Honda, Suzuki, Kawasaki, and Yamaha – often love competing with each other with bikes that more or less have the same goal, but sometimes wildly different paths to get there. Given how much Japan’s motorcycle brands loved to try to best each other at building the same thing, it was only natural that the big four also got into turbocharged motorcycles. Turbocharging was seen as a sort of “free” energy. Exhaust gases are normally waste products, but with a turbo, those gasses can be used to force more air into the combustion chamber and increase power.

All of these motorcycles were born in the golden age of the turbocharger. Cute metal snails appeared in everything from everyday cars to products that had nothing to do with forced induction. Seriously, in the 1980s, you could buy turbo-themed shoes and even computers.

Suzuki was late to the turbo bike game. By the time Suzuki entered the market, Honda and Yamaha already had turbo motorcycles on showroom floors, and the aforementioned Z1-R TC was out there scaring the bejeezus out of riders. Being late to a party is not great, but if you must arrive after the festivities have started, best to bring something the others don’t have. That’s what Suzuki tried to do with the XN85 Turbo. This wasn’t the first, second, or even third bike to go turbo in Japan, but it was the first to right the wrongs of other turbo motorcycles.

Not Too Big, Not Too Slow

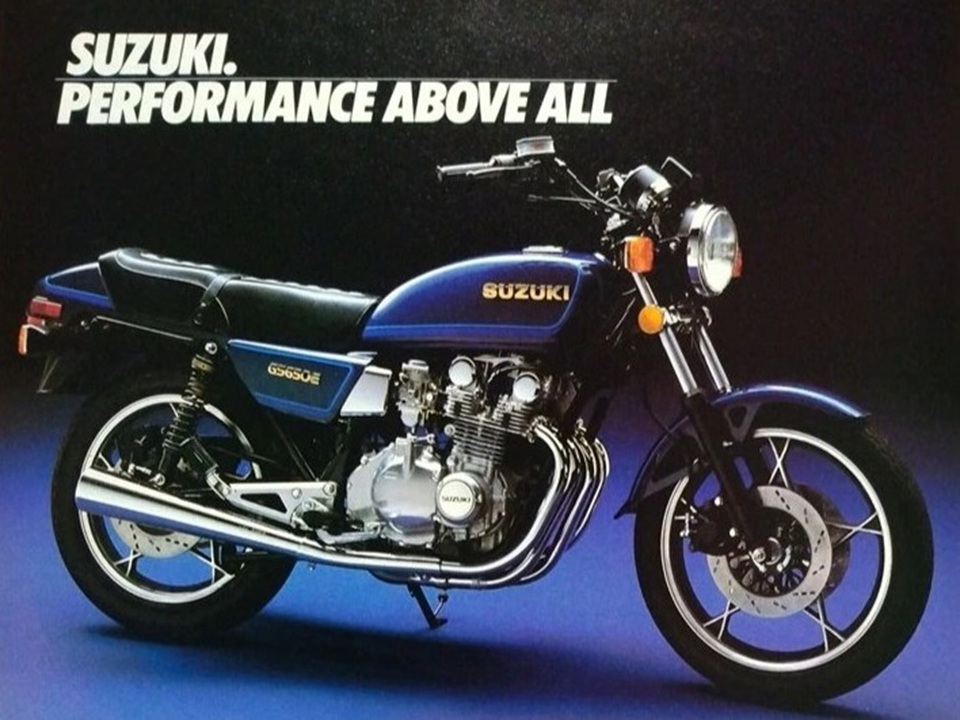

Suzuki’s turbo bike actually began with another machine, the Suzuki GS-650. As Cycle World explained in 1981, the 650-class of motorcycle rose as a middle ground between big bikes and little ones. Motorcyclists of the 1980s loved 250s because they were light and easy to ride. Going up to a 350 meant a bigger bike, but not meaningfully more power. You could then go up to a 500, which did get you exciting power, but now the size and weight advantages of the lower classes were gone. At the same time, a 1980s 500 wasn’t an ideal touring machine. Sure, you could carry two people and luggage, but you’d be wringing it out on a hill while battling traffic.

The 650 was seen as a sort of Goldilocks bike. It had enough power to pass traffic while loaded up, but was also still in the middleweight range, and thus didn’t ask riders to straddle a beast of a 750 or even larger. By the early 1980s, the 650 formula was tried and true, with the Japanese and the British having launched successful models.

Suzuki came out swinging with the GS-650, a motorcycle sold in three flavors: a sporty bike with a chain drive, a cruiser-like machine with a shaft drive, and a tourer with a shaft drive. Cycle World details some of the GS-650’s development:

The GS650 is a new exception to the usual practice where a manufacturer designs one engine to be used for both shaft and chain drive models and then adds the shaft drive gear assembly as an afterthought. The GS650G uses a different motor than the chain driven E model has, the main difference being in the use of a plain bearing crankshaft on the shaft drive 650G. The E model follows traditional Suzuki practice in retaining a roller bearing crank. Suzuki seems to be changing over to plain bearing engine designs with each new model produced, so it may have decided to go with plain bearings while it had a clean design slate on the shaft version, while using existing GS550 tooling to produce the more conventional E model.

Suzuki comes from a long two-stroke tradition where roller bearing mains are normal practice and, like Kawasaki, has had no problem in making strong and reliable roller cranks for four-stroke use. But plain bearings also work very well on fourstrokes and are generally cheaper and easier to produce. Plain bearings also run quieter than rollers, a consideration on a shaft drive bike where owners are more likely to fit fairings that reflect engine noise back at the rider. Much higher oil pressures are required to lubricate plain bearings, however, so the 650G uses a heavier duty oil pump than either the E model or the old 550, its higher pumping pressure creating a slight horsepower drain at operating rpm. Such miniscule power losses of course are of little importance to those who would choose the shaft over the chain drive. In any case, the G makes plenty of power, as we’ll see.

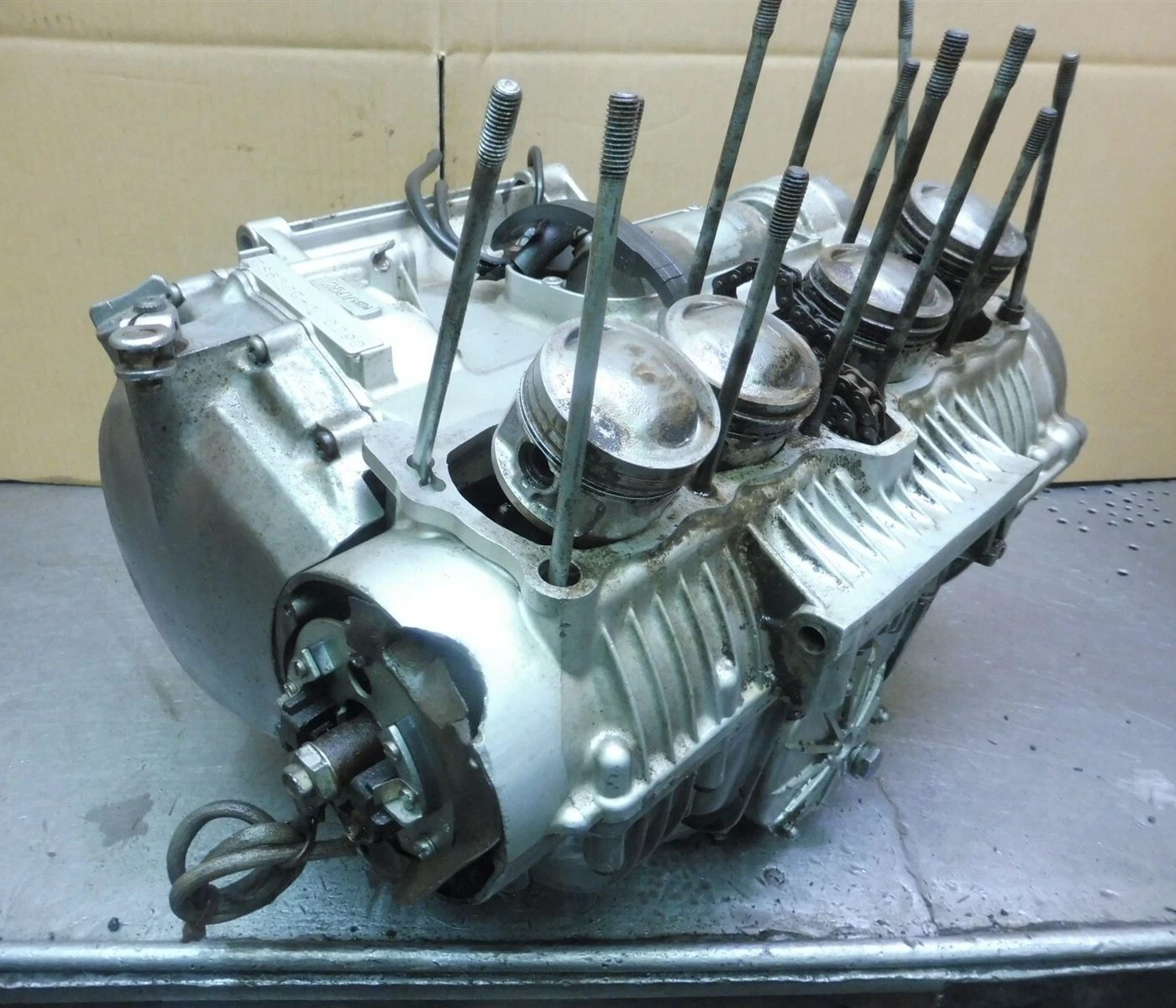

Elsewhere the engine follows normal Japanese inline Four practice, with double overhead cams acting on shimmed buckets. The shims are on top of the buckets for easier changing and adjustment. Like the 550, the 650 uses only two valves per cylinder, but the combustion chamber is an all new design, machined into what Suzuki calls a Twin-Dome chamber. The small combustion chamber has been cut into three concave pockets, one for each valve and one for the spark plug. The valves are slightly offset in the chamber with the exhaust valve closer to the center of the engine. In addition to helping swirl the incoming mixture, this offset allows the spark plug to crowd in closer to the center of the combustion chamber. Central location of the plug, as in fourvalve heads, is not possible, but by using the small D-type (12mm) plug and moving the exhaust valve slightly inward, a near central location is possible for balanced flame propagation.

The GS-650’s inline-four sported a high 9.5:1 compression, flatter pistons for better power, and a piston dome design intended to reduce the interference with the flow of the incoming air and fuel charge. The GS-650 engine was more efficient than the 550 and burned cleaner. Cycle World notes that the engine’s innovations meant that it was able to maintain a high compression ratio without detonation even when burning low-lead gasoline. The efficiency was clear, too, as a GS-650 was able to hit 60 mph even with a heavy right hand on the throttle.

The GS-650 would go on to impress the motorcycling press and consumers alike. But what’s important here is that the 650 was also the original base for Suzuki’s turbo motorcycle.

Smaller Motorcycle, Bigger Power

Suzuki’s Hamamatsu Factory began turbo development in 1979, and the engineers’ choice to go with the GS-650 was logical. The whole promise of a turbocharged motorcycle is to get big bike performance out of a smaller machine. Besides, in choosing the GS-650, the engineers wouldn’t have to deal with all of the extra weight of a literbike before adding even more weight with the turbo system.

According to Classic Motorcycle Mechanics, the engineers almost immediately ran into challenges. The four-cylinder turned out to be a good choice because of the smoother exhaust flow compared to a twin. This was great for driving a turbocharger.

What wasn’t so great was the detonation, otherwise known as uncontrolled combustion in the cylinder. Boosting the GS-650 engine led to so much increased heat and combustion pressures that Suzuki engineers blew up countless engines trying to make the turbo work. Reportedly, engineers wanted to get 100 HP out of their boosted powerplant.

Another problem that Suzuki’s engineers ran into was that it was difficult to control the turbo. Ideally, Classic Motorcycle Mechanics notes, the turbo needs to be close to the engine’s ports. But the design of the GS-650 engine meant that the turbo could be close to one set of ports, but not the other. Too much exhaust pipe distance, the magazine said, and the GS-650 turbo project experienced a laggy response from the turbo as the exhaust gases lost some energy en route to the turbo.

Suzuki’s solution was to route the exhaust under the engine, direct exhaust flow to the turbo through a single pipe, and place the turbo right above the transmission. This was a lot of piping, which did impact turbo responsiveness, and Suzuki compensated by improving fuel delivery. Fuel was delivered through injectors and metered through an electronic module. By this point, both Suzuki and Honda already had experience in motorcycle fuel injection, so the application of FI in this Suzuki wasn’t as novel as it would have been in the past. Further improving how snappy the engine was is ignition advance. When manifold pressure is low, the ignition system advances to improve engine response.

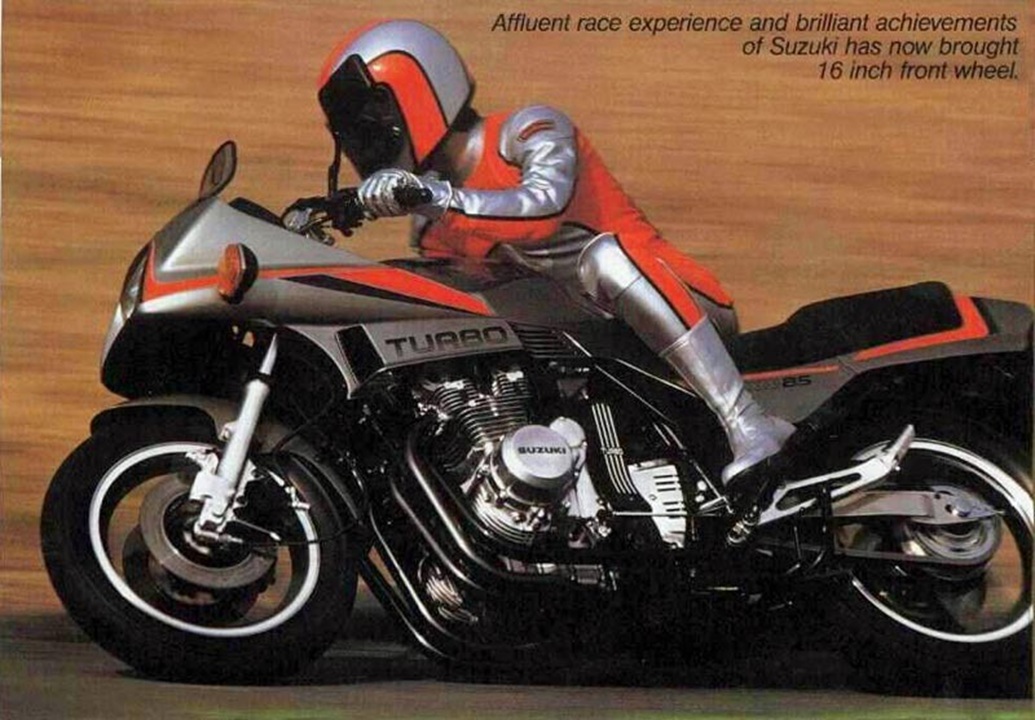

Suzuki’s engineers eventually figured it out, and in 1982, the XN85 was announced. It would go on sale a year later. The XN85, which had GS-650 bones and Katana-like looks, made no effort to conceal its mission. The “85” in its name pointed to its output, a healthy 85 HP.

The XN85

Cycle World continues with the changes that evolved the original GS-650 turbo project into what became the XN85:

The XN85 also gets a thorough mechanical massage underneath the turbo. Like the other 1983 turbos, the XN85 is built on a 650cc engine. It is not exactly the same engine used on the GS650E or G, because it has the plain bearing crankshaft found on the G models, and the chain final drive of the E model 650 Suzukis. Like the other 650 Suzukis, the XN85 engine has four air-cooled cylinders lined up across the frame. A pair of camshafts spin on top of this engine, popping open two valves for every cylinder. The 62mm pistons travel through a 55.8mm stroke, providing 673cc. This displacement is considerably larger than that of last year’s Honda CX500 Turbo, and slightly larger than the 653cc of the Yamaha Turbo, but is exactly the same as that of the new Honda CX650 Turbo.

Though the displacement is the same on the turbocharged XN85 as it is on the normally aspirated GS650 Suzukis, many of the parts involved are not the same. Pistons with flatter crowns are stronger and provide a lower (7.4:1) compression ratio. These are connected through larger wrist pins to stronger rods that transmit power to the heavier plain bearing crank. A clutch with two more plates, improved friction plates and a new release mechanism transmits this power to a new transmission with different gear ratios and larger gears. The lower three ratios are closer together on the XN and the top two are spaced farther apart than on the standard GS650, the final ratios working very well with the new engine’s powerband. Most of the top end parts are shared with the normally aspirated model, including valve train and cams, but the oil circuit includes passageways around the exhaust valve seats to help cool the seats and valves. Cooling oil jets spray the bottoms of the pistons, too, and a half-liter larger oil supply helps extract this additional heat through an oil cooler in front of the engine. Stronger steel head and base gaskets are used between the new head, the new cylinder assembly and the new crankcase.

Since the first three cylinder, twostroke Suzukis, there have been all manner of air scoops on the top of Suzuki engines. The standard 650 has small scoops on the cam covers, but the XN has larger scoops directing air to the center of the cylinder head. It uses plastic snap-on scoops at the lower edge of the small fairing to conduct air to the engine. An oil temperature gauge is included in the instrumentation to tell the rider how all this cooling equipment is doing.

The XN85 was boosted with an Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries (IHI) turbo with a 50.4mm diameter on its exhaust turbine and a 48mm for the intake. Honda also went with a tiny turbo for its turbo bike. The reasoning here was that the power from a baby turbo was more controllable. In the past, there were aftermarket turbo kits available for motorcycles, but these used car turbos. When these turbos spooled up, the motorcycles took off like a scalded cat. But the keyword there is “when,” because the threshold for a small motorcycle engine to spool a car turbo was so high that the boost didn’t kick in until the end of the rev range.

At the same time, Suzuki didn’t copy the homework of its competition. While Honda and Yamaha implemented their turbo systems to deploy big power as you marched toward the top end, Suzuki went a different path. High boost thresholds and lag meant that the earlier turbo bikes weren’t always smooth to ride. It also meant that, unless you were at high RPM, these bikes weren’t any faster than a non-turbo equivalent. If anything, the increased weight and exhaust backpressure at low RPM made them slightly slower.

A Turbo Bike That Didn’t Need A Waiver

Suzuki’s solution to the complaints of other turbo bikes was to go with a milder tune to begin with. The IHI turbocharger delivers a moderate 9.8 PSI to 10.5 PSI of boost, and the power comes on at around 5,000 RPM to 6,000 RPM. The magic of Suzuki’s setup was that, by going mild, they gave riders a motorcycle that could be ridden hard through corners without fear. From Cycle Guide, July 1982:

Below 4000 rpm the XN feels much like a standard GS650, and the tach needs to be in the 5500 to 6000 rpm range before the turbo makes its presence felt. And even then you don’t get a bulletfrom-a-gun punch, just an ever-increasing surge of power from the 10.5 pounds of boost. Turbo lag isn’t much of a problem on the Suzuki, and with the engine spinning at 6000 rpm, the XN85 certainly will rush out of corners. Power seems to start falling off at around 8000 rpm, but the Turbo still will breeze up to 120 mph with consummate ease, and should be capable of reaching its theoretical top speed of 135 mph. Suzuki claims that the Turbo is nearly a second quicker than a standard GS650 in the quarter mile, with a time of 11.7 seconds.

At those speeds the Suzuki’s racer-like riding position and quarter fairing become more than cosmetic items. They make the Turbo comfortable at any speed, especially above 100 mph, where European riders will enjoy a relaxed ride.

Such high-speed comfort isn’t available on many motorcycles, and neither is the XN85’s light and predictable handling. In fact, the only thing that plenty of other bikes have is the Suzuki’s horsepower. And being known for everything except its power makes this Suzuki a very unusual turbobike.

Cycle World had similar thoughts in its review in April 1983:

Most of the Turbos have an extremely sudden, almost violent, transition. The Suzuki is different. The bottom end doesn’t feel as relatively weak as the others, and the top end doesn’t feel as strong, because the transition is more gradual. This is likely the result of the long exhaust plumbing, reducing the turbo response, which is not so good, but making the boost more controllable for the rider, which is good. As it is, you aren’t immediately aware when the Suzuki comes on boost. The bike just keeps going faster as the tach climbs, and it’s time to shift and start again.

Even though the XN85 comes on boost more gently than the other Turbos, it still feels stronger and has better throttle response when the engine is spinning above 5000 rpm. This is a smooth running engine, too, making full use of the rpm range more acceptable than it would be if the engine vibrated excessively at high rpm. No rubber mounts are used anywhere on the frame; the motor just isn’t a shaker.

The motorcycle press especially praised the XN85 for its handling, with some publications praising the handling far more than the turbo. Suzuki equipped the XN85 with a 16-inch front wheel, which was novel at the time. Going with a smaller wheel and combining it with a competent chassis and suspension meant that the XN85 was surprisingly agile. Cycle Guide said the motorcycle’s sub-500-pound weight and low riding position made the XN85 easy to toss into turns. The magazine said that the XN85 rode so well that the handling was the real headlining feature, not the turbo.

There was a lot more to the XN85 than just handling and boost, too. Like other turbo bikes, Suzuki decided to slap “Turbo” badges all over the thing. There was even a turbo badge that was reversed on the front of the XN85, so drivers ahead who looked in their mirrors knew that you meant business. Add a bikini fairing and glorious graphics, and you have a motorcycle that couldn’t have existed in any other period than the 1980s.

Suzuki also cared about who would ride and wrench on the XN85. Early turbocharged bikes had a knack for allowing their turbos to spool up to the high heavens, eventually destroying the engine. Suzuki really didn’t want that to happen. So, a wastegate limited boost pressures. If you were silly enough to try to disable the wastegate, the motorcycle had one more redundancy: If boost got too high, it cut spark to slow you down, only turning it back on once boost got back to safe levels.

Suzuki tried its best to make sure that the parts under the plastics weren’t completely unique to the XN85. The Honda CX500 Turbo used a custom ECU that cost $300 to replace when it broke; Suzuki engineers adapted a common car ECU to work with the motorcycle, a unit that only cost $71.85 to replace. Likewise, Suzuki also priced its replacement turbos lower than its competitors. The XN85’s price, $4,700, was slightly cheaper than the earlier turbo bikes, too.

Nobody Cared

Alright, so it sounds like Suzuki had this turbo bike thing figured out. The XN85 didn’t blow itself up and delivered its boost in a usable, non-death-defying way. Suzuki even made it handle really well. Real-world testing even suggested that the XN85 got 50 mpg so long as you were not in boost.

The XN85 sold from 1983 to 1985 worldwide, and then, like the other turbo bikes, it vanished. Only 1,153 examples of built, of which around 300 made it to America. So, what happened? Why did nobody buy this?

One reason came from within. Suzuki also sold a 750cc four alongside the XN85, and the naturally aspirated 750 made 72 HP and cost only $3,500. Why would you pay $1,200 more for 13 HP and way more complexity?

Suzuki also failed to resolve some of the other issues that turbo bikes suffered from. At lower speeds and lower RPM, the XN85 was no faster than a cheaper naturally-aspirated motorcycle. As Cycle News wrote in 1996, all of the turbo bikes had more or less the same problems: They were too heavy, too complex, too big, and weren’t fast enough unless you rode them like a maniac.

In my eyes, the problem with all of these bikes, at least when they were new, is just the fact that you paid a lot more money for not a lot more power. Then, it wasn’t long before Japan started making more powerful engines without forced induction, rendering the turbo bikes obsolete.

Yet, I also understand why the turbo bikes have a huge following. These motorcycles were truly novel, and if you like the feeling of getting kicked by a horse at a certain RPM, the turbo bikes cannot be beat. They also look like nothing else, with all of the wedges and decals that ’80s vehicle lovers adore. Also, if you’re a daring tuner, it wasn’t too hard to make these motorcycles ridiculously fast.

The other good news is that these motorcycles, like pretty much all of the turbo bikes, aren’t particularly collectible. You can still get them for under $10,000, which is great!

All of these turbo bikes are still amazing. Everyone was so obsessed with turbos and thought that they would be the future. Technically, everyone was right, at least when it came to cars. As for bikes? Well, naturally aspirated engines work just fine in most situations, and electric motors fill in the gaps otherwise. Still, it’s amazing these bikes happened in the first place. Suzuki even went through the work to make a better turbo bike, too, but the XN85 just couldn’t overcome its limitations.

Top graphic images: Mecum Auctions; Suzuki

I think that complexity vs. price was a big part of the problem when buying new, but at that time, you could buy a brand new 2 year old leftover GS1000 for like $3K.

I was a Suzuki and BMW dork then and Suzuki was the Japanese manufacturer with the guts to sell the Katana, the GS1000G – an astonishingly competent bike, and the GS1000S – a bigger more powerful R90S.

Turbos were rare until the GPz 750 Turbo came along. Those things were everywhere and not terribly remarkable after a while. But seeing an XN85 was and still is a rare treat.

If I recall correctly, Honda wound up sending a bunch of 650 Turbos to the same fate as their fully faired CBXs – instructional bikes for mechanics’ schools. Am I remembering that correctly?

The Barber Motorsports Museum in Leeds, AL has all 4 of the 80’s Japanese turbo bikes on display together. (Along with about another 1,000 bikes)

Very cool place that is well worth the visit for motorcycle fans.

Wish I had known about this place when I had a project in Birmingham oh 20 years ago. But maybe it didn’t exist then.

My first bike was a Suzuki GS550. After a ride up an old volcano on a dirt road and destroyed the chain, I wished I had a 650 shafty. I would take the slight energy penalty of a shaft drive over the fairly constant adjustments and lubrication required of a chain.

Barber opened in 2003. Funny I lived in Birmingham for 7 years but visited it more when I lived out of state than when I lived there. Funny how we tend to take local attractions for granted. I haven’t been back since I left but heard Barber greatly expanded the museum since. I’ll have to make it there again some day.

After riding shaft drive bikes for 25 years I would struggle to go back to a chain.

Just had a rental Harley Pan America with chain drive and the chain had 6 inches of play by the I dropped it back off after a week. I can’t see going back to adjusting chains every couple weeks.

That place is amazing and I hear it has only gotten more so. I went in 2006, spent about an hour with the wife and kid, dropped them off at the hotel and went back for three hours. Standing close enough to touch Hailwood’s TT winning Ducati, with oil still spattered on the sprocket and his name chalked on the tires? Goosebumps.

I spoke to the docent and Mr. Barber insisted (at the time) every motorcycle be 2 hours away from being on the track. Only two were exempt, a movie prop and one other (I forget which). Not that he would expect someone to do laps on a 1986 GSX-R750 with 20+ year old tires, but the expectation was these were not museum pieces, but actual motorcycles in a museum. They own two bespoke race bikes of which only 1 was ever built. They were so thorough about the collection, they found enough parts to complete the second one.

Barber is a cool guy. The first time I was there was when I was working as pit crew for my brother when he was racing WERA. He crashed and damaged his exhaust. Somehow Mr. Barber heard about it and came by and told my brother to unbolt the exhaust and come with him. He took my brother and the exhaust back to the museum shop and had one of his guys tig weld a repair. While that work was being done Barber gave my brother a personal tour of the shop and off limits area.

(While this was happening I was in the pits putting my brother’s crashed bike back together)

That’s awesome

Looks over at corner of conference room. Sees the XN85 that’s been stored there since 2002, indoors, nice and temperature controlled, under a plastic sheet and last ridden in the 90s…1995 to be exact. I wish the Autopian allowed pictures. It was one of two that crossed paths in my life. Only this one remains. It has kind of blended in with the rest of the furniture, sometimes I forget it’s there.

OK some context on said conference room is needed….

Nice to see Autopianism continues to extend to bikes. Even today, the motorcycle industry continues to churn out the variety, weirdness and, occasionally, total crappitude that should generate entertaining content for years. Better than today’s soporific car industry, I’d say. Pocket-bike culture next please!

I loved my 90HP 1983 Yamaha SECA Turbo 650. Scalded cat indeed, but I never found the turbo to be unpredictable. It’s out in my shop and runs fine, but I don’t ride it anymore (I’m 73). It’s top-heavy, and I don’t feel like recovering from an unexpected weakness in a hospital.

I ride a contemporary concours zg1000 and the smooth fueling from the carburetors is almost enough to make the frequent carb rebuilds worth it.

I’ve been driving an 80s ford fuel injected truck recently and with the primitive batch fire injection I get the feeling that early efi bikes were probably a nightmare to ride smoothly. The shear mass of the truck and the engine components tend to mask how abrupt the fueling changes are vs a more modern ecu.

I fuel injected a dr200 a couple of years ago with a microsquirt clone and it took 150 maps before I could get a smooth transition from closed throttle to open throttle. Even now that bike will buck you off below 3500rpm at the transition if you’re not paying attention. I remember that this was still a complaint in the magazines when the supersports were switching to efi.

Anyone that’s ridden one of these, how was the fueling?

I was really impressed(?) at how much they crammed into that frame.

One argument: I would say that today is actually the golden age of the turbo. They are in everything (but motorcycles). It was part of the zeitgeist in the 80s but nobody I knew actually had one.

Turbo-tastic!

I love those translated to English text boxes in the brochure pictures:

“Affluent race experience and brilliant achievements of Suzuki has now brought 16″ front wheel”

“Easily manipulated turbo realized through ideal air-fuel mixture ratio. Produced through the novel mechanism”.

“Suzuki make it – so make it Suzuki”

Reminds me of the early Honda user manuals:

Speaking of translations; In the sixties there were banners at racetracks proclaiming, “Suzuki Are Here!”

Could be the English usage where entities like corporations are referred to as plural vs American usage where a corporation is singular. UK mags and sites will say “Ford are planning…” where in the US we’d say “Ford is planning…”

The translation might not be the problem, but rather the English dialect it was translated into. I hope that’s helpful.

OK. I learned something. Thanks! I are appreciative. Seriously, I see what you’re saying.

Hehehe… what a fantastic line. I have to find more of these.

I’m always tootling people with vigor

Pretty rad that they took a page out of BMW’s 2002 Turbo playbook with the reversed script “turbo” at the front. Nothing quite says “get the f*ck outta my way” like seeing something displayed normally in a rear view mirror. Cool.

“Obrut? Isn’t that the turkish guy next door?”

The nostalgic part of my brain loves all those pictures of 1980s bikes!

I’m thinking about 850 to 950 – a bridle idle, really. Too much higher and the centripetal horseforce gets really high. At what RPM do you like your horse to kick you?

This question will likely show how little I know about bikes, but here goes. Would the new breed of electrically spun turbos work well in bikes to help fill in the torque curve at the bottom, same as they’re being used in cars? Or does adding the electrical system to be able to spin up the turbo add too much weight and complexity for a bike?

Turbos add too much complexity for the performance gain (the same issues as we had in the 1980s), which is why they haven’t made a comeback yet.

I think that an electric turbo would put too much load on the charging system – only the big touring bikes have any real excess electrical capacity and sizing that system up would add a lot of weight. The Kawasaki H2 is probably as close as we’ll get to an electrical turbo as it uses a mechanically driven centrifugal supercharger (basically half a turbo).

The biggest reason we doesn’t see many turbo bikes is because NA liter bikes already make more power than can be put to the ground through the rear tire on a short wheelbase vehicle. They either spin the rear wheel or lift the front. Manufacturers employ sophisticated traction control and wheelie control to take away the power shown on the dyno and spec sheet when actually riding on the street.

So you would be adding extra cost and complexity for no extra real power at anything near street legal speeds.

That said Honda has shown an electric turbo V-Twin recently so who knows if they might make one as a technical showpiece. (The Autopian did a article on it a few weeks ago)

(Liter bikes stopped getting faster in the 1/4 mile at about 150 hp)

V3, actually. They just showed it around at EICMA in October. 800ccish displacement, full liter power. It’ll carry a small battery to run the turbo.

Think of it as a hybrid, except that the electric motor kicks in to provide intake boost, not tractive power. I think it’s got potential. Kawasaki has a hybrid bike and has had a supercharge H2 in production for a few years. While Honda’s making some headlines with a pretty drawn out development process, I’d expect Kawasaki has the skills and experience to bring this to market in an effective and scaleable product.

Yes, it was a V3. Cool technology but not actually very practical. A NA 800cc bike has plenty of power for the street without a turbo. Again, this is bench racing – tech for technology’s sake

The Kawasaki H2 is also cool tech that is completely impractical for street riding. The Ninja 1000 is the sweet spot there and still has more power than can be put the wheel at legal speeds.

The Transalp 750 is the most interesting bike that Honda has put out in quite awhile. Great bones but big misses by not spending a few dollars for tubeless wheels and cruise control. (I won’t buy a new large capacity bike with tubes or without cruise control in 2025)

There’s no point. Modern bikes already make more power than their tires can put down, and without electronic aids they are easily capable of lifting the front end off and slamming the rider into the pavement backwards.

Adding a turbo to that is just a faster way to get killed, but won’t improve your lap times.

True but liter bikes today are sold based on dyno specs not the reality of what is available on the street. Buyers love to brag that their bike has 200+ hp even if the electronics take that away when they twist the throttle.

Manufacturers have been bench racing with liter bikes for about 20 years – which is when they stopped getting faster in the 1/4 mile because HP met the limits of physics.

Spotted the cars only person.

A friend of mine in the 90’s had a Seca Turbo and let me take it on a couple road trips. It wasn’t fast to today’s standards – my VFR800 would spank it like a bad monkey – but turbo bikes are a hoot. And it had a boost gauge!

When the turbo didn’t sell, Yamaha offered a boost upgrade kit that basically recalibrated the wastegate and would cause the needle on the boost gauge to go well into the red zone. I was always surprised that the kit didn’t recalibrate the boost gauge.

Good grief, that turbo placement is sure to cook you in traffic. Explains why the rider’s leathers actually a blast furnace suit.