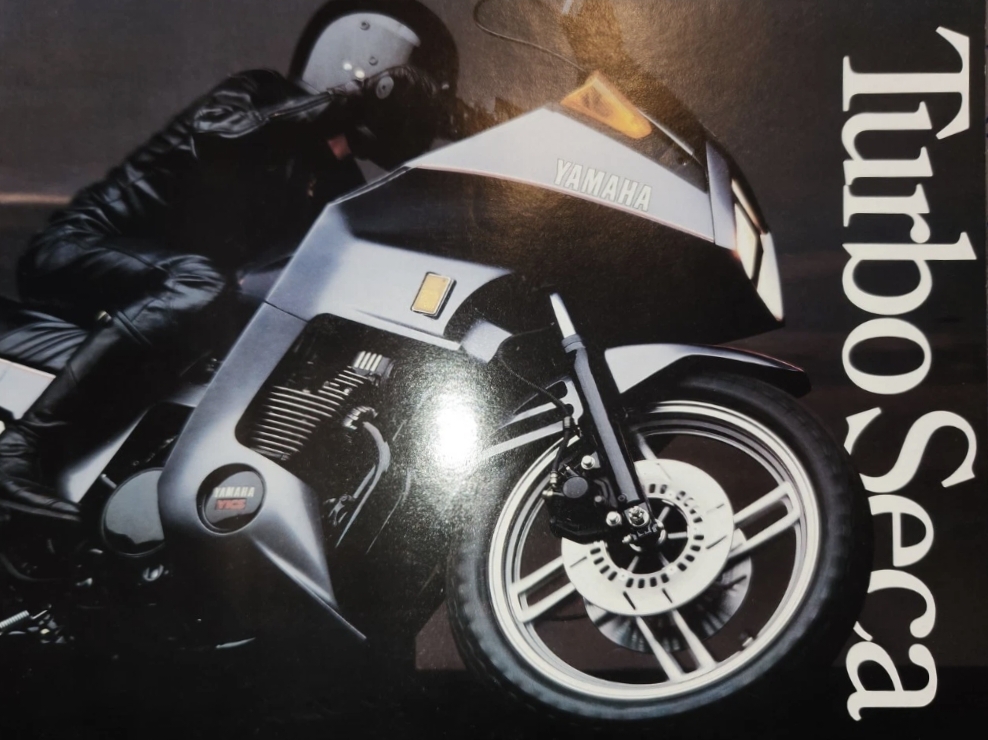

Japan went through a wild period of innovation in the 1970s and 1980s. The nation turned into an electronics powerhouse, and its vehicle industries transformed from underdogs into household names. One of the craziest blips during this period was when Japanese motorcycle makers thought the future was in turbocharging. The big names in Japanese motorcycling each built their own complicated turbocharged bikes, and Yamaha thought it had the best idea yet. The Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo was supposed to solve all of the problems with decades-old turbocharged motorcycles. It was fast, hot, and complicated, yet it still failed.

Japan’s former obsession with turbocharged motorcycles didn’t even last a full decade and produced relatively few machines. The whole turbo motorcycle concept then sort of died off, became obscure, and never really came back to mainstream brands. Sure, Kawasaki sells a supercharged motorcycle today, but superchargers aren’t turbochargers. Honda is developing a boosted motorcycle, but it doesn’t use a turbo, rather an electric-powered compressor.

The concept behind the turbo motorcycle of the 1970s and 1980s seemed like a solid idea. By strapping a tiny turbo onto a middleweight motorcycle, Japanese firms thought they could create the best of both worlds. In theory, these bikes would punch out power and acceleration like larger literbikes, but handle like middleweights while getting great fuel economy when off boost. Basically, it was like getting two motorcycles in one.

That fuel economy aspect was also vitally important as the world was still recovering from a decade with more than one oil crisis. Saving gas was in vogue. The best part, or at least in theory, was that these power gains were essentially free. To these manufacturers, exhaust gases were just free energy that was wasted out of the tailpipe when they could be redirected to a metal snail to make power.

Turbocharging in motorcycles wasn’t exactly new in the 1970s. By that time, there were already various kits that a biker could buy that mounted a car’s turbo onto their motorcycle. These kits were known for comically high boost thresholds, but once the boost kicked in, the bike and its rider took off like Wile E. Coyote on a rocket. But it wasn’t long before the motorcycle manufacturers themselves started slinging turbo bikes.

Amazingly, there are still two more motorcycles I have not written about in this series of Japan’s turbo motorcycle history. The Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo launched in 1982 after the Honda CX500 Turbo, and like the Honda and the Kawasaki Z1-R TC before it, the Yamaha was built to be stupid fast. But it also suffered from pretty much the same problems as other turbo bikes of the era.

Yamaha’s Big And Comfortable Four

The Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo was based on one of the greatest technological leaps forward for Yamaha, the XJ650. In a retrospective written for Yamaha by racer Ken Nemoto, he says that the 1980 XJ650 and its predecessors helped Yamaha lay the foundations for large four-cylinder motorcycle handling. These foundations, Nemoto says, are still present in the firm’s big bikes today.

Nemoto notes that, in the 1970s, Yamaha’s competition, like Honda and Kawasaki, were quick to build astoundingly quick four-cylinder, four-stroke superbikes. Suzuki was late to the four-stroke four-cylinder party, but it chased a similar formula. Yamaha, on the other hand, stubbornly persisted in building big twins. This resulted in the launches of 650cc XS-1, the TX500, and the TX750, each of which failed to captivate the riding public, who were all obsessed with fours. In 1976, Yamaha then launched a big triple with the GX750, but once again learned the hard way that people wanted a big four.

Eventually, Yamaha got the message, and in 1976, it finally decided to chase its rivals in earnest by greenlighting development of a four-stroke four-cylinder. Here’s what one of Yamaha’s engineers said about the ride and development of the XJ650:

Talking about its development, [Chief Engineer, Road Testing Unit, 2nd Project Engineering Division, Takafumi] Fujimori says, “The concept or goal for the model was ‘200 kg, 200 km/h.’ This was groundbreaking at the time, and it was a target that would be impossible to reach without coming up with new methods for everything, including the way we’d think about its development. We aimed to bring in a new age of compactness and light weight. The decision for a displacement of 650cc also came from this idea. We put everything we had into creating a bike that handled well. It was about compiling everything we’d learned and achieved until then into one vehicle. This meant that right from the design stage, we included elements like weight distribution and chassis rigidity into the mechanical drawings, and it was also the first time we ever brought in the test riders to help while the model existed solely on paper.” He’d had such a difficult time since the development of the XS-1, so the XJ650 clearly was a special model for him.

“Discussing how we did things for the TX and the GX, we worked together with the engineers to figure out what to do for things like the machine’s center of gravity. By putting the alternator behind the engine, we were able to make the bike slimmer, more compact and further centralize the chassis’ mass. The results were clear from the first shakedown rides, and I could feel how this bike was really something different. The engineers that had struggled with us through the process shared in the achievement, and we all agreed that we had to make sure this kind of handling would be passed down to future Yamaha models.

I still think that the XJ650 was the first truly Yamaha 4-stroke bike we ever made. It also was probably the first time the engineers felt so much joy in developing a 4-stroke model. Even when we re-analyzed the bike with the latest technologies, its chassis balance was good, and it proved that we had put together a really solid motorcycle.”

Yamaha says it wasn’t just the handling that made the XJ650 a superstar, but the engineers’ attention to detail when it came to the surfaces that riders interacted with.

The fuel tank was shaped just perfectly for riders to grip it with their knees. A lot of time was also spent on the handlebars. Yamaha didn’t want riders to feel like they had to fight the bike to turn, and found out that by lowering the ends of the bars, the rider and the motorcycle felt like they were closer to being one. More than that, Yamaha says, it also reshaped the brake lever and clutch lever so that they could be depressed with only a couple of fingers, which meant that the rider could keep their hands on the bars.

This time, Yamaha didn’t miss. The XJ650’s four-cylinder was rated at 73 ponies, and the bike weighed only 500 pounds when loaded up with five gallons of gasoline. It also had an easy-to-maintain shaft drive, and with a light enough rider in the saddle, an XJ650 was able to dispatch the quarter mile in the 12-second range. Depending on the exact flavor of XJ650 that you bought, you basically got a European-style riding experience for only $3,000 ($12,495 in December 2025 money), or less than the price of a sportbike from Europe at the time.

The XJ650 did not light the sales charts on fire, but it was still a step in the right direction for Yamaha. This was a bike that could carve corners and then ride across the country. If you restrained your right hand, it was even possible to return 50 mpg on an XJ650, which meant a riding range of around 250 miles.

Yet, Yamaha wasn’t done. While the XJ650 might have been good, Yamaha was also acutely aware of the growing obsession with turbocharging. It joined in on the rush, and out of the other end came the Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo.

The Rational Turbo

As Cycle World wrote in 1982, it wasn’t Yamaha’s original intention to boost the XJ650. At first, Yamaha’s early experiments into turbocharging involved boosting the already quick XS11. Yamaha mounted a fuel injection system to the XS11’s engine and then coupled the mill to a turbo. Now, this was a bike that already made 95 horses and sped to 135 mph in stock form. Technically, it really didn’t need more power. But Yamaha did it, anyway.

The results of this 1981 experiment were as you would expect. Boosting a 1,101cc engine from the 1970s was an insane endeavor. As it was, 95 horses were a lot for a motorcycle with a 1970s frame, a 1970s suspension, and 1970s tires. Yamaha figured out that making it even faster didn’t make any sense, as there were few riders in the world crazy enough to ride such a beast. Then there was the fact that the tires were already near their limit at 95 HP.

So, Yamaha decided to copy the homework of Honda and the Turbo Cycle Corporation by using a turbo to make a middleweight motorcycle perform like a 1,000cc motorcycle. Like the competition, the goal became to make what was more or less two motorcycles in one. A tame and fuel-efficient middleweight for getting around town, and a snarling beast for carving canyons and tracks.

Yamaha’s method to achieve this wasn’t as ambitious as Honda’s. Team Yellow wouldn’t go with electronic fuel injection or try to reinvent the wheel. Instead, the bike maker went with simpler solutions for an easier machine to live with. Cycle World details how Yamaha added a turbo to the XJ650 platform:

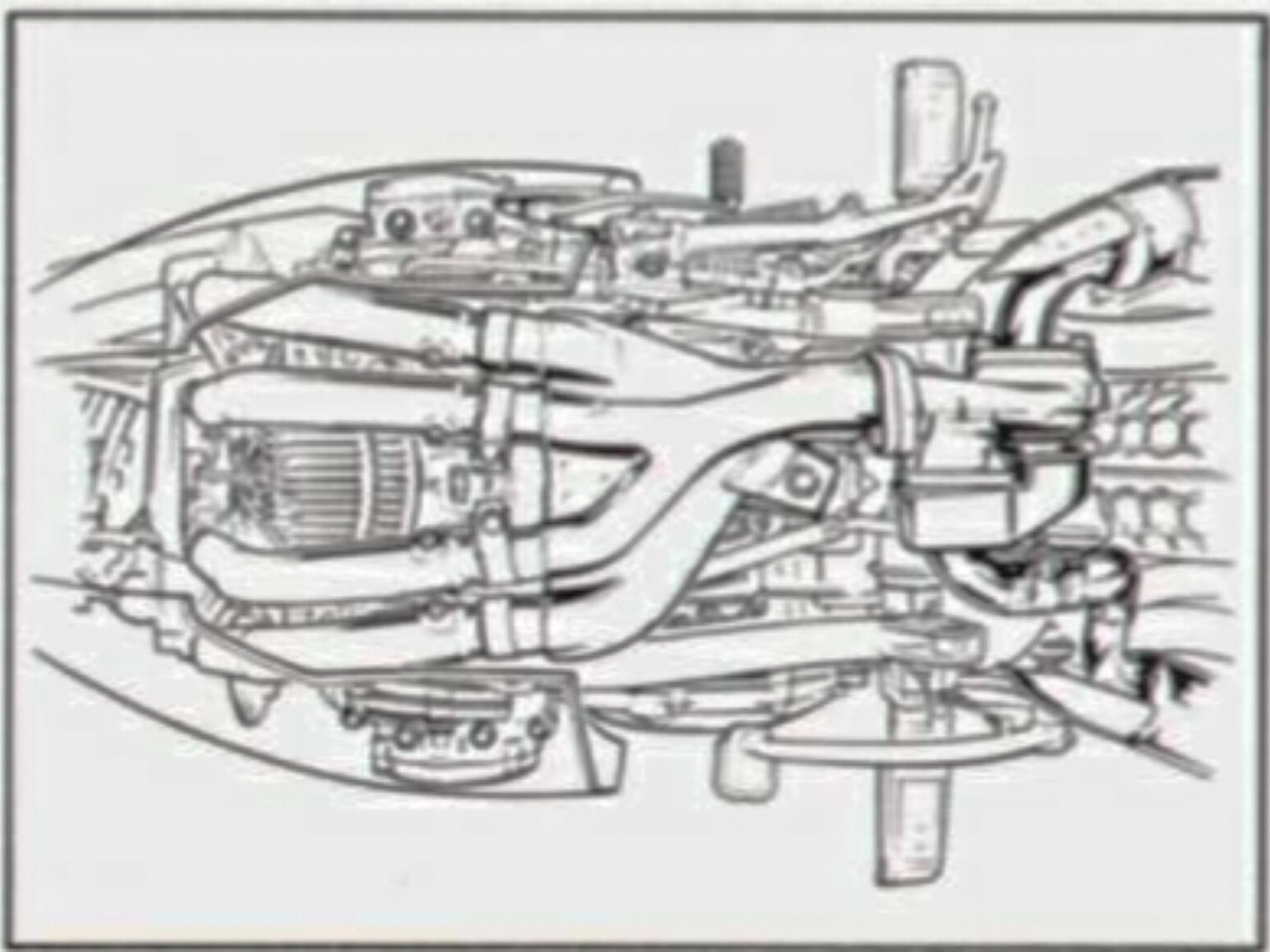

Though the fairing and bodywork of the Turbo Seca lend the bike a fairly exotic and complex look, the turbocharger and its associated plumbing have been grafted on in a reasonably clean and simple fashion. Exhaust gases leave the engine through header pipes with inner walls of stainless steel and are funneled into a manifold beneath the engine. The manifold pairs the #1 and #4 exhaust pipes into one pipe, and the #2 and #3 pipes into another before they reach the manifold. This allows the exhaust pulses to be evenly spaced as they enter the turbo, driving it more efficiently. A wastegate bleeds off excessive pressure when the boost goes too high, feeding excess exhaust into the right side muffler. The left muffler receives only exhaust gases straight from the turbo.

The turbocharger itself is a Mitsubishi TCO3-06A unit and is claimed by Yamaha to be the world’s smallest. With a turbine diameter of only 39mm, it can spin safely up to 210,000 rpm. The turbine shaft rides in a bearing-within-abearing, as do most other modern turbos, reducing the destructive speed that any one bearing surface might have to withstand. The bearings and shaft between the turbine and the compressor are pressure lubricated with engine oil from the main oil gallery on the crankshaft. There is an added scavenging pump in the engine to draw oil away from the turbo.

The compressor side of the turbo draws air in through the air cleaner under the seat, pressurizes it and sends it into a surge tank just in front of the carbs. The four 30mm C V carbs are not just any C V carbs, but are themselves pressurized from the outside in, so to speak. They have special drillings around the throttle shafts to provide a back-pressure against the turbo boost, preventing leakage or misting of fuel and air from joints and shafts in the carb bodies. The float bowls also receive regulated pressure from the surge tank to stabilize fuel levels. Fuel is supplied by a pump, cable driven off the end of one camshaft, and the regulator sends excess fuel back to the tank.

Yamaha left much of the chassis untouched. As Cycle Guide wrote in 1982, the turbo version of the XJ650 has the same frame, steering geometry, and wheelbase. Instead of giving the turbo bike a new frame, Yamaha just changed some of the brackets on the existing frame and routed the turbo and its plumbing around the existing structure. This was notable, the magazine noted, because it meant that the Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo was the only turbo bike from Japan (as of 1982, anyway) that did not have a modified chassis. It also meant that, aside from the metal snail, the bike’s guts looked similar to the naturally aspirated version, too.

That said, while the XJ650 Seca Turbo was sometimes called the “rational turbo” and the “simple turbo,” there was still some wizardry going on. From Cycle World:

Yamaha has worked hard to eliminate the dreaded “turbo lag”, a characteristic that is more damaging by word of mouth than it generally is to actual riding characteristics of the machine, as in the case of the Honda Turbo. In any case, Yamaha has come up with a clever way of eliminating the condition. Turbo lag appears when the throttles are whacked open at low boost, when the engine is drawing air faster than the turbo is supplying it. This results in a momentary intake vacuum that causes the engine to go flat. Yamaha’s engineers have worked around this by installing a set of reed valves between the surge tank and the air cleaner. If the throttles are opened and there is a temporary intake depression, the reeds flap open and allow a normal flow of air to the carbs. As boost pressure catches up and -builds in the surge tank the reeds flap shut, sealing the boost pressure to the carbs. The surge tank also houses a relief valve, so if a waste gate malfunction or other problem causes overboost in the surge tank, a poppet valve opens up and releases the excess.

Simply turbocharging an engine and then standing by for more power is not enough, of course. A turbo makes an engine much more sensitive to detonation, and the added power imposes loads and temperatures well beyond those found in the non-turbo version of the same engine. To eliminate the detonation problem, Yamaha uses an electronic vacuum advance/knock sensor. One part of the electronic vacuum advance unit senses vacuum in the intake tract and tells the ignition governor unit, an electronically precise way of doing what most vacuum advance units have always done, i.e. retard ignition when the throttles are open and the engine is under load. The other part of the advance system is a knock sensor located in the cylinder head. This picks up the first faint rattle of detonation in the combustion chambers and slowly retards the ignition timing just enough that the knock ceases. An engine makes its best power when timed just” short of destructive detonation, and the knock sensor moves the timing around to keep it at that point, regardless of load, throttle opening, or fuel octane rating. Motorcycle and car racers who have holed pistons may wonder where this sytem has been all their lives.

The 650 engine itself has been substantially changed to handle the added turbo load. Compression ratio has been dropped from 9.2:1 on the regular Seca to 8.2:1 on the Turbo. Pistons are forged instead of cast aluminum and the crown material is 30 percent thicker to with-* stand the heat. Added piston cooling is provided by an oil drilling in the connecting rod that sprays oil onto the bottom of the piston crown. The crank has been double-drilled for better oil flow to the rods and the surfaces of the big end rod bearings have been given oil retention grooves, though bearing material is unchanged, as are rod and pin dimensions.

Other changes to the XJ650 platform include a cranked-up oil pump to provide up to 70 percent better oil flow, a reinforced transmission, a stronger clutch, and larger cooling fins on the engine. Of course, Yamaha also followed the same path its rivals did and subjected the XJ650 Seca Turbo to wind tunnel testing. Out of the other end came fiber-reinforced plastic fairings that make the bike look like it was doing 100 mph while sitting still.

As for the engine, that 39mm Mitsubishi turbo was good for 7 PSI. This pushed the 653cc inline-four from around 73 HP to up to 90 HP peak. The engine was also good for 54 lb-ft of torque. Top speed was in the ballpark of around 126 mph or 127 mph. Due to the sort of weird piping arrangement, the turbo was located only a few inches or so ahead of the rear tire. In a modern review, the enthusiast publication of Shannons Insurance joked that it’s like having an automatic rear tire warmer.

The Better Turbo

Alright, numbers are nice and all, but how did it ride? Here’s a snippet from Cycle Guide‘s review:

In roll-on acceleration in all gears and at all rpm, the Turbo is exactly as fast as the unblown Euro 650. And that’s doubly impressive when you consider that the Turbo’s effective gearing is a smidgen taller than the Euro’s (all the ratios are identical but the LJ’s rear tire is about half an inch taller) and that it weighs 65 pounds more.

Any acceleration similarities end, however, once the Turbo is on the boost. In the lower gears this 650 pulls like a strong 750, and in the taller ones it sprints down the highway like a literbike stuck on fastforward. As with most turbo machines, the LJ’s quarter-mile numbers are not a true measure of the bike’s peak acceleration, since there’s a bit of delay—turbo lag before that peak is reached. Moreover, the Turbo’s maximum boost (7 psi) isn’t high enough to deliver astronomical horsepower figures, and full boost doesn’t kick in until the engine is revving up near 5000 rpm. Nevertheless, the amount of turbo lag on the Yamaha seems unusually low simply because the engine performs so well when it’s off boost. That’s why there are seldom any sudden burets of power as the engine makes the transition from off the boost to on it, especially in the higher gears. The rate of acceleration just gradually and smoothly changes from ordinary to omigod, much like what you feel in a jetliner during takeoff.

Despite the unoriginality of its chassis, the Seca Turbo handles quite nicely, thank you. Understand, of course, that it is not a bike meant to fulfill the peg-dragging fantasies of 18-year-old canyon-crazies; no indeed, this is something more along the lines of a sport-tourer, a bike that you can ride fast, lean far and profile to your heart’s content, but that’s not the ticket for ten-tenths comer berserking. For one thing, the nature of the powrer delivery gives flat-out cornering an abnormally high degree of difficulty. Using high rpm in the turns can unleash more acceleration than you want, while lower revs can deliver less than you need. And then there’s the added weight that has transformed the mid-size Eurobike into a liter-class heavyweight. Fortunately, a lot of that additional weight is low, meaning that the center of gravity hasn’t been noticeably raised. So the Yamaha doesn’t resist leaning or sit up while braking in a turn the way Honda’s 549-pound, high-cg Turbo does. But side-to-side transitions are more sluggish on the LJ than on the plain-Jane 650, and you can’t bank the blown Yamaha into any kind of turn as easily. Full-on cornering also causes the tires to squirm a bit, letting you know that they’re nearing their limits.

In short, it sounds like Yamaha almost solved the big problem with the turbo bikes of the 1980s. This was a turbo bike that didn’t lose power at lower RPM, and was still controllable when the boost hit. So, why did I call this bike a failure early on in this? Well, Yamaha might have engineered its way around boost “lag” well enough, but the other issues with old turbo bikes were unavoidable.

Why The Old Turbo Bikes Failed

The first problem was that all of the reinforced guts and turbo componentry added 65 pounds of dry weight to the XJ650 chassis. The fact that the boost came on late also meant that, according to Cycle Guide‘s testing, while a naturally aspirated XJ650 ran a quarter mile in 12.83 seconds at 103.4 mph, the turbo did the same deed in 12.61 seconds at 104.7 mph. Some magazines got their turbo test units to slice a half-second off the naturally aspirated XJ’s time.

Helping the turbo was Yamaha’s addition of an air-assisted fork and adjustable air shocks. But then came the price. At $4,999 ($17,178 in 2025), the Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo was $2,000 more expensive than a naturally aspirated XJ650. For most buyers, all this really meant was that buying an actual literbike made more sense. A real literbike was more controllable in corners, wasn’t more expensive, got roughly the same fuel economy, and didn’t have a complicated turbocharging system on it.

The turbo Yamaha sold for only two years, 1982 and 1983, before fizzling out. Yamaha is estimated to have built around 6,500 units in 1982 and another 1,500 units in 1983. A Yamaha XJ650 Seca Turbo is not the rarest bike in the world, but it’s also not common. That being said, the Yamaha does appear to be one of the least popular Japanese turbo bikes to collect. I have seen these for sale for a very reasonable $2,000 or $3,000, which is wild for the sort of vintage technological marvel that you’re getting.

The Yamaha once again shows why the Japanese turbo bike efforts of the 1970s and the 1980s were a dead end. These motorcycles made a ton of sense in concept, but cost too much money and had too many quirks for buyers to latch on. For most people, just buying a bigger bike from the start made more sense than buying a smaller bike that used a metal snail to be like a bigger bike.

The rest of the motorcycle industry, including Japan’s manufacturers, also eventually figured out how to get more power from naturally aspirated engines of all sizes, rendering turbocharging largely obsolete for street bikes. Today, if you want more power, you just buy a bike with a bigger engine. Still, all of Japan’s turbo bikes are a window into a future that could have been. It’s wild that even the motorcycle that was called the simple turbo still had some incredible engineering behind it. Perhaps in some weird alternate reality, every motorcycle has a turbo just like so many cars do today.

Always thought these are super cool. Would love to have one.

The friend who taught me to ride back in the ’80s had one of these. I wanted one.

What these were was an attempt to make a sports-oriented bike with the power of a literbike that dodged the Harley tariff, a 35% tariff on bikes over 700cc.

My first bike was 1980 Suzuki GS550E and the reason I bought it was because the frame was big enough for 6’2″ me to be comfortable on it. The Yami’s and Kawi’s in the same class were too small for me. Even with a Plexifairing, that bike was so stable at 100. But the shaft drive of the Yami, would have appealed to me. I hated dealing with the chain.

Fast forward 45+ years, and I’m riding a Honda ADV 160 scooter. Lol!

The price went from $3000 to $5000, while the performance was barely improved from 12.8s 1/4 mile, to 12.6. No wonder these didn’t sell.

I have a 1983 turbo seca that looks exactly like your pictures. I haven’t fired it up in awhile, though. I decided I really didn’t need that much go-fast in my life.

I believe Kawasaki’s first true production turbo was the GPZ750 Turbo, not the Z1R TC (the TC being really just an approved aftermarket kit).

This is 100% correct. A friend had one and it was seriously quick and deadly. Easier to ride bc it was fuel injected , but would bite hard if you were not careful. It was slightly faster than my Suzuki Katana 1000. A very nice bike IMO.

When these bikes didn’t sell well, Yamaha introduced a free “Power Up” kit that kept the wastegate closed longer and increased boost from 7psi to around 12psi (and pegged the boost gauge). Yamaha must have had a lot of confidence in the engine to make that change.

My first bike was a 1981 Yamaha Seca 750. The engine was a punched out 650 and was sweet but the chassis wasn’t great. It would develop a weave over about 85mph that wasn’t dangerous but it was uncomfortable.

Not that you need the Mercedes, but an interesting rabbit hole might be all the ways motorcycle manufacturers tried to address brake dive.

I have a buddy who, just last year, rode an ’82 XJ650 Turbo across the country. Literally; Cali to central Florida. And not just a highway shot, I’m talkin’ the loooooong way. I believe they did around 4,000 miles, including a detour to go up Pikes Peak. Not a bad choice for altitude, but yeah not the steed I would choose for a cross country run. What a nut.

my dad was fully yamaha. had yamaha dirt bikes after graduating from hodaka’s. his one and only street bike was a leftover 75 XS500 that he enjoyed riding up until a close call with a truck passing a car into his lane ended with an inspaction of the ditch. i jumped ship and went team green with my first bike, a 96 KE100. that bike was my first taste of motorized freedom and i have fond memories of it. i had high aspirational visions of a ZRX1200r while riding that bike lol. my first and only street bike ended up being an ’06 triumph t100 which was a joy to ride. motorcycles seemed to evolve like the wright flyer to jets from the 70’s-90’s.

My first motorcycle was a 1983 Yamaha Vision, very similar in styling to the Seca but a much more advanced bike. Liquid-cooled 550 v-twin, vertical downdraft carbs, rear mono-shock, and the engine was a stressed member of the frame. I think the brakes were the biggest letdown compared to a modern bike, but with decent tires that felt like a genuine performance machine. Mine had a full fairing, black and gold paint, and those same split 4-8 spoke wheels, I still think it was a great-looking bike.

Honda really changed the game with the original CBR900RR in the early 90s.

Making a “1000cc” bike the same size/weight as a 600cc really killed ideas like this. Previously, for whatever reason, upsizing the engine translated into increasing weight substantially.

My first motorcycle was a 1982 Yamaha XS400R Seca, this bike’s baby brother.

The 4/8 spoke wheels were shared between the bikes and brought back memories upon laying eyes on the lede photo.

The 400R was a very rare starter bike in the USA – I bought it as abandoned property and spent the next couple of years teaching myself how motorcycles and carburetors worked. Missing bodywork was only available sporadically on eBay. I had to coat the tank to keep it from leaking; the Seca tank was bike-specific and unobtanium in the early 2000s, let alone today.

It was a ton of fun to wind out to redline basically all the time, everywhere.

Loving these deep dives into history. I’m struck by the similarity between the turbo bike experiment and Kawasaki’s hybrid bikes. They make the same claims, big bike performance from a mid size, but with better fuel economy. They also suffer from the same problems, complexity, weight, cost. I don’t think that means any of these bikes were a bad idea though, to me it’s important that companies keep trying this stuff and finding out what does and doesn’t work. Plus it gives us oddball rare bikes to marvel at decades later.

“I have seen these for sale for a very reasonable $2,000 or $3,000, which is wild for the sort of vintage technological marvel that you’re getting.”

There were a lot of model specific parts on it, that would be hard to get a decade later (this IME is a bigger problem with Yamaha than Honda&Suzuki), compared to the sisters with larger production numbers and therefore also more non-OEM parts. Restoring and maintaining running condition will take much more dedication than going to the next autoparts store in the village.

Oh, and drumbrakes. Glad they went out of style. It is not that they do not brake, it is the:

Apply pressure.

No braking.

Apply more pressure.

Still no braking.

Apply more pressure.

Maybe we are braking a little now?

Apply more pressure.

Skidmark!

I aspire to one day own one of these turbo bikes. They’re not super common down here in Aus but there are some of the Hondas up for reasonable-ish money.

With that complicated vacuum and carb system, I wonder how reliable these are?

“With a turbine diameter of only 39mm, it can spin safely up to 210,000 rpm.”

There’s an extra digit in that rpm number…right?

Nope, that’s the right RPM.

Turbo speeds are insane.

Looked it up and dang. I am having trouble conceiving of something that can go 3500 revolutions per second.

There are stationary flywheels used for energy storage, like batteries. Carbon fiber in evacuated chambers. I think they can go even faster than that.

210k RPM is impressive… for a 39mm turbo.

HOWEVER

It’s not spinning quite as fast at *only* 42,981RPM but with a 32km diameter it’s a HELL of a lot bigger:

“PSR J1748−2446ad is the fastest-spinning pulsar known, at 716.35 Hz (times per second),[2] or 42,981 revolutions per minute (1.3959 milliseconds). This pulsar was discovered by Jason W. T. Hessels of McGill University on November 10, 2004, and confirmed on January 8, 2005.

If the neutron star is assumed to contain less than two times the mass of the Sun, within the typical range of neutron stars, its radius is constrained to be less than 16 km. At its equator it is spinning at approximately 24% of the speed of light, or over 70,000 km per second.”

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/PSR_J1748%E2%88%922446ad

What I’ve learned from this series of articles is that there are good reasons for motorcycles to have naturally aspirated engines!

I really wish there was some off-the-shelf options to make liter-bike engines work in small cars. Obviously there will be fabrication involved in the chassis, but something to at least allow a reverse gear in transverse applications would be nice.

There are racecars using bike engines and some vehicles built with bike engines

Yeah, but I hear getting a reverse gear is tough.

Many of them have reverse and tolerance for extra torque.

Searching motorcycle engine powered cars, it seems easier than it used to be.

I’ve seen car transaxles used and modified bike transmissions, electric reverse drive and all sorts of variations.

The lower the weight, the more parts options there are, like wheelchair parts, rx7 bits, and with access to cadcam tooling, almost anything.

One variant feeds the bike trans output into a geo metro transaxle.

There was an interesting mid engine transmission built from a traditional rear drive car transmission that output past the axle, and ran sprockets on both sides forward to the axle inputs, driven by belts.