Chicago has depended on its trusty elevated rail system for well more than a century. Every day, some 400,000 riders board one of Chicago’s glistening ‘L’ trains to go to work, home, sporting events, and countless other spots in the city and its surrounding areas. Over those hundred-plus years, Chicagoans have ridden generations of legendary rail equipment. Over the weekend, I got to ride in a special piece of rail history, a 1959 6000-series railcar into the heart of Chicago. It was a transit ride like no other.

The Chicago Transit Authority ran the 6000-series railcars from 1950 to 1992. After their retirement, most of the 720 units were scrapped or converted into work cars, and then they were replaced with the 3200-series cars that remain in use today. The oldest 6000 that was still operating in 1992 was 42 years old and had been in Chicago its whole life. Only 13 of the 6000-series cars were preserved, of which only four are operational.

If you want to ride in a 6000, just like Chicagoans used to, you really have only one choice. The four operational 6000s, Nos. 6101-6102 and 6711-6712 are preserved and maintained as part of the Chicago Transit Authority Heritage Fleet Program. Last weekend, the CTA, in partnership with the Illinois Railway Museum – America’s largest train museum – ran what it called the Fall Colors Express.

This train gave railfans the rare opportunity to see Chicago from a more vintage point of view. Given its 66-year age, CTA Nos. 6711 and 6712 were properly vintage, but, at first, I wasn’t convinced of the idea of an excursion train through downtown Chicago. How would it be meaningfully different than just boarding a normal CTA train? While I may not have been convinced, my wife was, and she got us tickets. So, I had no idea what to expect, but we were locked in.

Little did I know, an excursion train through a city’s rapid transit network is surprisingly romantic.

A Clever Solution To Crowded Streets

Chicago’s ‘L’ lines are iconic. It’s hard to picture the city without its elevated trains thundering down the tracks between skyscraper canyons. Just look up pictures of Chicago and you’re bound to find the ‘L’ making appearances alongside other icons like the Willis Tower (formerly the Sears Tower), Navy Pier, and Wrigley Field. Chicago’s relationship to rail is arguably as legendary as the New York City Subway.

Back in the mid-1800s, a young Chicago found itself growing exponentially. As CTA historian Graham Garfield writes on Chicago “L”.org, the city was originally Potawatomi lands and then a small village near Fort Dearborn, started to become a Lake Michigan hub. Commerce and industry grew in Chicago alongside its population, and residents eventually found it difficult to get from their homes to their places of employment in the city.

Workers had to either walk to work or take a horse-drawn carriage. The problem was that countless residents could not afford to ride in a carriage, and walking was impractical. These issues would not be solved with the dawn of the automobile, because early cars were largely for the rich, and some folks even struggled to afford cars like the Ford Model T.

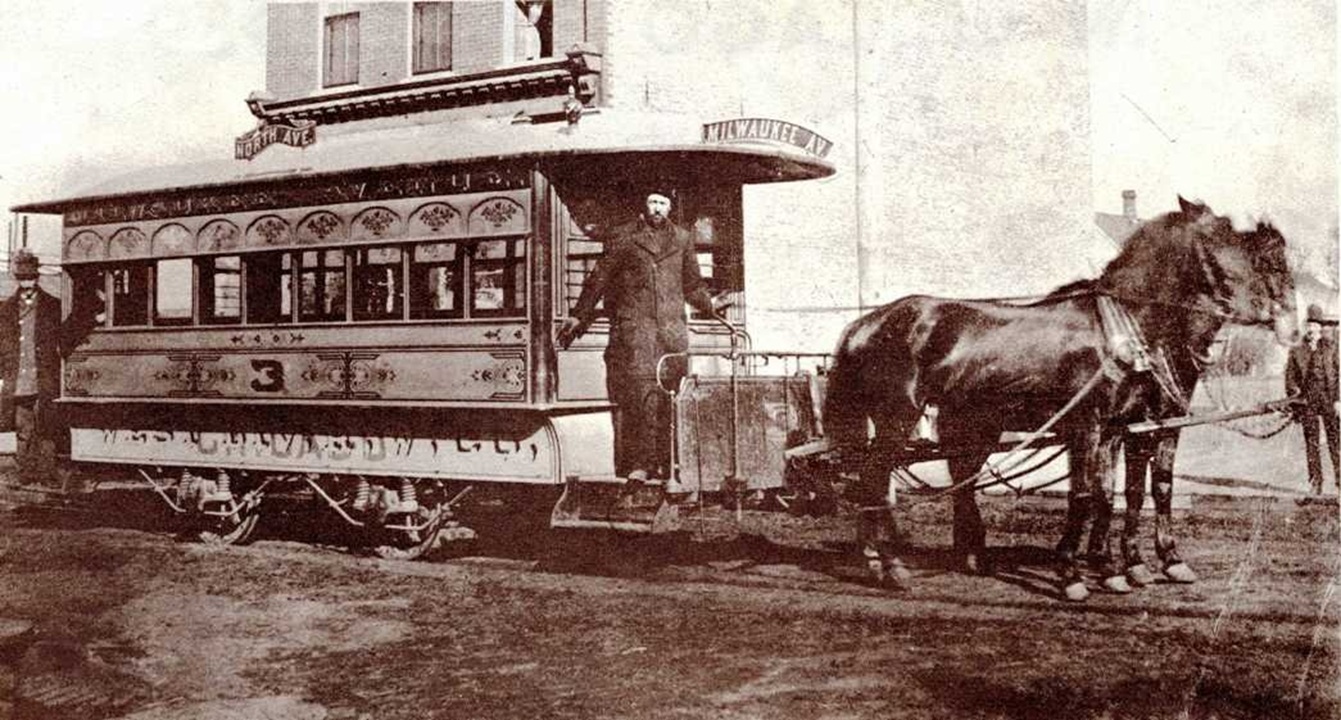

Chicago would not be where it is today if it weren’t for the seeds that were planted in the mid-1800s. Horse-drawn omnibuses hit Chicago in 1850, and they were one of the first solutions to Chicago’s transportation problem. As you can guess, a horse-drawn omnibus is the distant ancestor of the trolley bus and the motor bus. These were more or less wooden buses pulled by horses.

As the Chicago Public Library writes, however, the horse-drawn omnibuses of Chicago were too expensive for many riders. 1859 brought an incredible advancement in Chicago’s mass transit with the street railway. These so-called “horse railroads” worked a lot like those omnibuses, but instead of carriages rolling down a road, they rode on rails. The street railroads were cheaper than omnibuses because, thanks to the steel rails, the horses had an easier time pulling greater loads of people.

As time marched on, the horses were replaced with cables, like the streetcars of San Francisco. Then, the cable system was retired for electric propulsion, paving the way for the historic streetcars that railfans love today. Eventually, even the streetcars went away and were replaced with the motor buses that Chicago depends on today. Something neat about Chicago’s ground transit history is that, well, more than a century later, Chicago’s buses often drive the same routes the horse railroads used to run.

While horse-drawn railroads and streetcars were crucial inventions for Chicago and for mass transit in general, they had an unfortunate downside. As cities grew, their streets became filled with people walking all over the place, countless carriages, and, eventually, the automobile. All of these factors and more slowed down street-level transit, and thus, they were seen as only a partial solution to urban travel woes.

As the City of Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development writes, developers came up with a wild solution. If the streets were too crowded for efficient streetcar travel, what if the streetcars were raised above the bustling streets? The first elevated railroad was proposed in Chicago in 1869, but it did not get the green light from the city.

This didn’t deter others, however, and between 1872 and 1900, more than 70 companies were incorporated in Chicago to create an elevated rail system. Of those companies, only six managed to construct elevated rail systems for passenger use. While this sounds crazy, it wasn’t unheard of. New York City has had an elevated railway since 1867.

The first of Chicago’s lines was the Chicago and South Side Rapid Transit Railroad Company, which entered service in 1892. The railroad was only 3.6 miles long in a straight line. This track ran adjacent to alleys, giving it the nickname the “Alley ‘L.’” Today, the CTA Green Line follows the same historic route.

The North Shore Line

One of the greatest advancements in Chicago rail was the Chicago North Shore and Milwaukee Railroad, better known as the North Shore Line. This line, which connected to the ‘L,’ allowed travelers to go from the Chicago Loop to Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

As American Rails writes, the North Shore Line started small. In 1891, the Waukegan & North Shore Rapid Transit Company was incorporated as a transit rail system for Waukegan, Illinois. Even years later, the railway was sold and reorganized into the Chicago & Milwaukee Electric Railway. At the time, the line reached Lake Bluff and Highland Park. Under new ownership, the new Chicago & Milwaukee Electric Railroad was extended to Evanston, Illinois. By 1905, the line extended north to Kenosha, where it connected to Milwaukee Light, Heat & Traction Company trackage. Eventually, the 85-mile line became one of America’s definitive interurban railroads and was known for its speed, cleanliness, and convenience.

In 1916, the line would fall into the ownership of business magnate Samuel Insull, who modernized the unit into the Chicago North Shore & Milwaukee Railroad, and worked out deals to allow the railroad to get direct access to Chicago via the ‘L’ trackage. Trains.com notes what happened next:

In the early 1920s, traffic between Waukegan and Evanston reached the saturation point of the line, which was handicapped by stretches of street running. The railroad saw that a new line a few miles west along the right of way of one of Insull’s power companies would be cheaper than just the construction of temporary track needed to rebuild the existing line. The first 5-mile portion of the new Skokie Valley Line was opened in 1925 and was operated by Chicago Rapid Transit, which continued to operate local service until 1948. The entire line opened in 1926 and became the new main route. The Shore Line, as the original route was termed, was relegated to local service. The new route was much faster, materially helping the North Shore compete with the steam roads. North Shore quickly became America’s fastest interurban. In addition, the North Shore emphasized its parlor and dining service—it was perhaps the only interurban to have much success with such operations.

In 1931 the Great Depression finally got a grip on the North Shore. The line declared bankruptcy in September 1932. Even so, the road continued to operate fast, frequent trains. It cooperated with parallel Chicago & North Western and public agencies in a line relocation project through Glencoe, Winnetka, and Kenilworth, eliminating grade crossings and street running. In 1939 the North Shore ordered a pair of streamliners from St. Louis Car Co.: the Electroliners. No other trains of the streamliner era had such disparate elements in their specifications: 85-mph top speed (North Shore’s schedules called for start-to-stop averages of 70 mph) and the ability to operate around the 90-foot radius curves of the Chicago “L.” World War II brought increased traffic, and the North Shore emerged from bankruptcy in 1946 — just as competition from automobiles and strikes by employees began to cut into the road’s business. Waukegan and North Chicago streetcar services were taken over by buses in 1947, dining car service on trains other than the Electroliners was dropped in 1949, local streetcar service in Milwaukee was discontinued in 1951, and the Shore Line was abandoned in 1955.

The North Shore Line would fall in 1963. This story is important because the rails I rode on are a part of Chicago and North Shore Line history.

The Skokie Swift

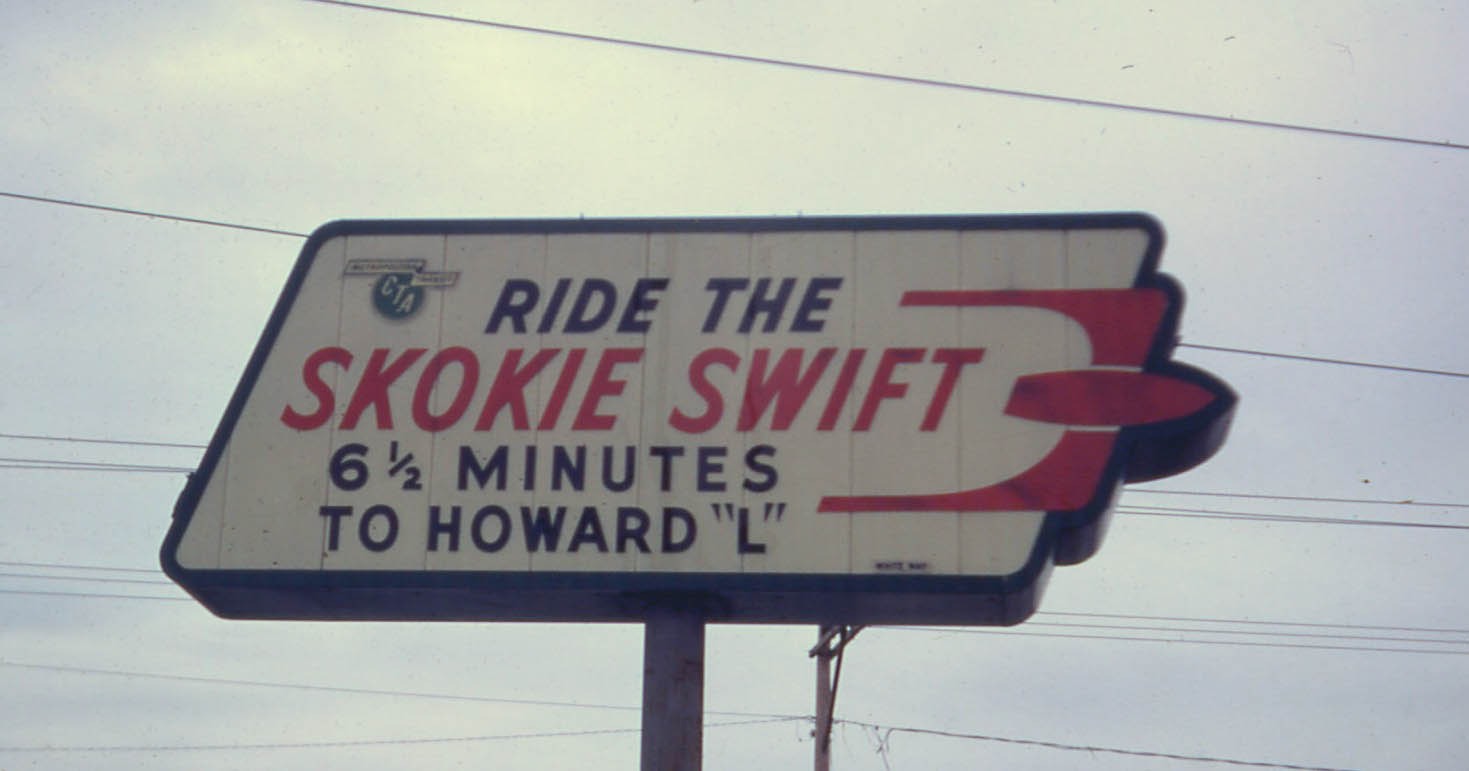

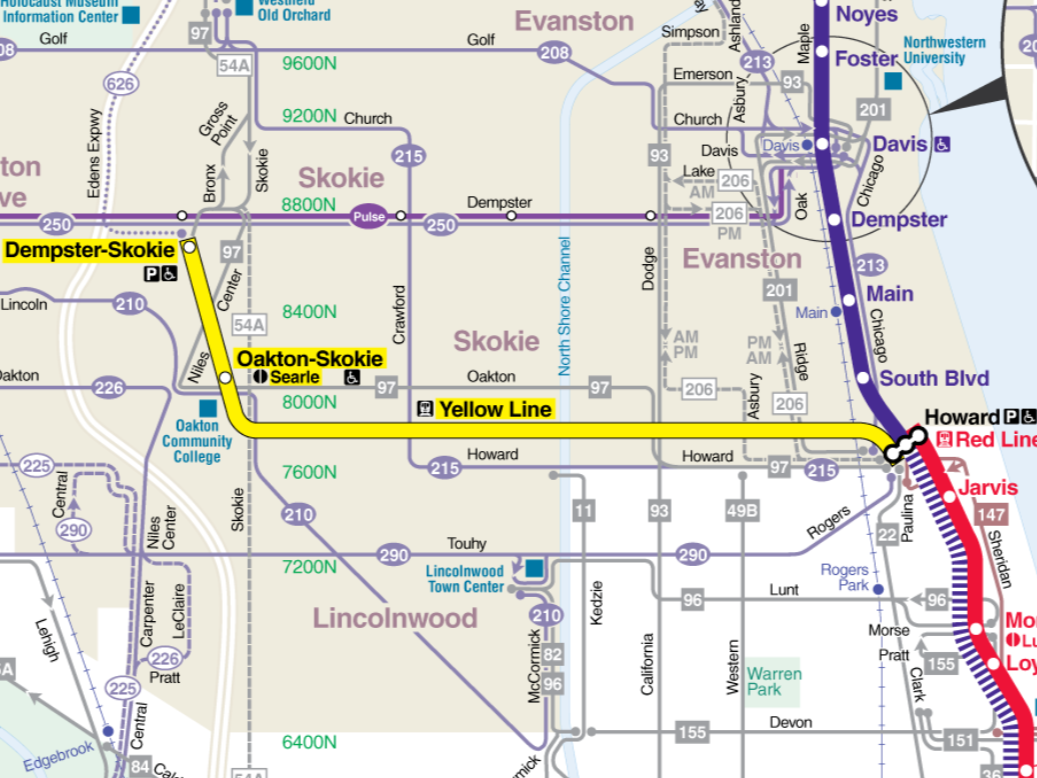

In the years immediately after the line’s failure, most of the North Shore Line’s rails were removed. In 1964, the Chicago Transit Authority purchased five miles of trackage between Howard Street in Chicago and Dempster Street in Skokie. CTA called the line the Skokie Swift, and it was a short, but high-speed line that moved passengers five miles in only 6.5 minutes.

Under CTA control, the line was massively successful, and ridership quickly more than doubled from the numbers reported by the former North Shore Line. What made the Skokie Swift work so well?

The CTA decided to run the Skokie Swift as a non-stop express train to Howard. Later, an intermediate station was added at the Oakton–Skokie stop. The line also convinced many Chicagoans that they didn’t need a car to get to work and back. Instead, they could hop on a short and fast light train and leave the car at home. The CTA really leaned into this by ensuring the Skokie Swift‘s Dempster station parking lot was massive for everyone who wanted to take the train. The stations connected to bus lines, an area where a taxi or a loved one could pick you up, and on the Howard end, Chicago’s ‘L’ lines. The Dempster station was also cleverly close to the Edens Expressway, making access easier for drivers who didn’t want to brave Chicago traffic.

The Skokie Swift wasn’t just a great commuting tool; it also became the shining example of how well rapid transit from the suburbs to Chicago could really work.

In 1993, the CTA renamed its ‘L’ system to color coding. The Skokie Swift became the Yellow Line. However, existing signage wasn’t changed, and if you look closely, you’ll still see Skokie Swift advertised on the line. The Skokie Swift is also a properly weird line. A portion of the line runs in a below-grade trench, and there are a handful of level crossings along the line. The Yellow Line is also the only ‘L’ train that doesn’t reach the Chicago Loop.

Sadly, the massive success of the Skokie Swift didn’t last. Today, the Yellow Line is the least used line in the ‘L’ system, and ridership has fallen below even the former North Shore Line numbers. Conditions were made even worse in 2023 when a Yellow Line train collided with a CTA snowplow, injuring 38 people.

The Fall Colors Express

Last weekend, a flurry of railfans parked at the Dempster station to take part in an excursion train. The Fall Colors Express saw railfans boarding classic CTA 6000-series railcars and seeing the best of Chicago by rail. The name is sort of a double entendre, which I adore. The colors on the ticket were yellow, orange, red, and brown, the same colors as fall, but also the same colors of the lines that the excursion train traveled down.

The CTA Heritage Fleet describes the train I got to ride in:

Railcars 6101-6102 were built by the St. Louis Car Company as part of the CTA’s first order of 130 cars of the 6000-series, numbered 6001-6130. Subsequent orders brought the fleet size up to 720 cars. The 6000-series represented a total departure in rapid transit car design for Chicago. The older and heavier wood and steel car designs of the 1890s-1920s gave way to lightweight cars whose all-electric propulsion and braking utilizing technology first developed for PCC streetcars by the Electric Railway Presidents’ Conference Committee (PCC) in the 1930s.

Unlike earlier cars, they were permanently coupled in pairs (“married pairs”) with only one motor cab facing outward from each car. Dual-paneled folding “blinker” doors were placed along the sides of each unit instead of at the ends for more efficient movement in and out of the cars; seats were permanently fixed facing opposite ends from the middle. Cars 6001-6200 originally required the conductor to stand between cars to operate the doors, but the door controls were subsequently relocated inside the cars.

The first 200 cars, including 6101-6102, were the beginning of a modernization process intended to remove from service the remaining turn-of-the century wooden units still in use. Beginning with car 6201, the remaining 6000-series cars—including 6711-6712—were built using motors, trucks, controls, and body components salvaged from PCC streetcars, which were relatively new but being phased out by CTA in favor of buses. The 6000-series made up the majority of the CTA ‘L’ fleet for many years, but began to be slowly retired in the late 1970s. By 1981, 6101-6102 were the last 6000s with their original dual-headlight configuration (starting with car 6200, the design had been changed to a single headlight, and all other earlier cars so modified). Largely out of passenger service and consigned to work train service by 1990, 6101-6102 were kept as historical vehicles, making occasional appearances at various events.

Each 6000-series car weighs 41,700 pounds and has bodies made out of aluminum. This makes the 6000s a lightweight design, by train standards. Power comes from a quartet of WH 1432LK traction motors, and the cars utilize all-electric brakes. On average, each car seats 47 people with room for standees.

My ride was on a chilly and cloudy Saturday, but there was excitement in the air. Railfans gathered at the Dempster station and watched commuter trains arrive and depart, picking up and dropping off only a few passengers at a time. Sadly, our train, which was supposed to depart at 16:30, arrived about half an hour late. But everyone was still excited, and there had to have been about 100 cameras all taking photos at the train’s arrival.

Most of the people who came for this were Chicago residents. Some of them even took a Yellow Line train or a CTA bus to get to the event. I live about an hour west of Skokie, so I was one of the few who drove a decent distance just to ride public transit, which felt a little goofy. But sure enough, the Dempster parking lot was so huge that there was plenty of space. I could only imagine how it felt to park here to dodge traffic in the 1960s.

The 6000s were vintage, yet they still felt familiar. They smoothly rolled across the tracks, and their interiors, while basic, were comfortable enough. The CTA trains of today are just like this, but more modern, shiny, and more accessible.

Once everyone was boarded, the train got underway with the instant kick of torque from the car’s DC motors. I was blown away by how much the Yellow Line wasn’t like the rest of the ‘L’ system.

You spend much of your time on the ground, rolling through grade crossings, and getting some surprising speed. The train recorded a peak speed of 51 mph during our run on the Yellow Line, which felt properly fast for this type of trainset. You also spend considerable time speeding in between neighborhoods. A ride on the Yellow Line feels closer to riding a Metra commuter train than the ‘L.’

We also got to experience the quirks of vintage equipment.

The track’s third rail stopped for each grade crossing, which meant that for a brief few seconds, the car didn’t have proper power. During these moments, the car reverts to a low power state, where the only lights that are illuminated are directly over the exit doors. Then, once the third rail reconnects, you feel a light jolt from the motors.

There are quite a lot of bridges and gaps in the third rail, which means that we spent much of our trip with the interior lights flickering. Have you ever watched a movie where an electric railcar’s lights flash? Well, if that car is old enough and runs on a third rail, that might not entirely be Hollywood movie magic!

The reason why you don’t see this in more modern trains is that they’re built to keep the lights going for those short moments the train is traversing gaps in the third rail.

Anyway, the Yellow Line was fascinating, and dare I say, it was far too short. The line terminated at Howard in a yard at the end of the Red Line, where our train continued.

The Red Line felt like a Greatest Hits of the northside, including Loyola University, the start of DuSable Lake Shore Drive, and Wrigley Field.

The red line took us toward downtown Chicago, where we joined the Brown Line. What was particularly exciting about this section was how it snaked through the concrete and metal canyons of Chicago.

As a CTA historian on board the train told us, all of the wild and seemingly nonsensical curves had a valid reason to exist. When these tracks were built, their constructors either had to use public land or buy whatever private land was in their way.

Sometimes, this didn’t go very smoothly as rich residents and luxury businesses didn’t want trains in their neighborhoods and some refused to sell. So, the elevated system was laid wherever builders could get permission and land.

These curves also mean that the trains going through the heart of the city are going a bit slower than they do in the outskirts. But that was fine. Everyone was able to get epic views of Chicago’s famous skyscrapers and the legendary Wacker Drive.

Something amusing that I noticed was that there were very few railfans along the way. Really, there were few people who cared at all about the train as it rolled by various stations. Most people quickly glanced at the train and then looked right back down at their phones.

That was weird to me. Sure, while the CTA does have fun with vintage equipment from time to time, it’s not like you see a 1950s railcar every day. The 6000s were taken out of service in 1992! That said, not everyone failed to react. There was one station in particular where almost everyone on the platform had their attention on the train. Some of them were excited, others were confused, like they thought the CTA was going to have them board something so old.

After the train snaked through the Loop, speeds picked back up again as we rode along the Orange Line into the south side of Chicago. CTA’s historian told us that the Orange Line allowed higher speeds because the line was designed to have stations roughly a mile apart. The track also stayed mostly straight. Here, it was neat to see the density of Chicago decrease from the Loop to become railyards, industrial properties, and what looked like to be quiet neighborhoods.

By this time, it was getting too dark to make out any major landmarks, so I kicked back and enjoyed the gentle movements of the 6000-series. Eventually, we reached the very end of the line at Chicago Midway International Airport. Given the darkness, the best way to tell we reached an airport was by looking at the blue taxiway lights in the distance.

The trip back to Dempster was the same, but in reverse. The cool part about the trip back was that the car I rode in was now the leading unit. CTA and IRM gave riders the opportunity to get right up to what was now the front window, and we got to watch the train cruise the rails.

Sadly, the day’s cloud cover meant that the train missed seeing a beautiful golden sunset. But in exchange, we got to see the night lights of Chicago. It was Halloween weekend, too, which meant that Chicago’s skyscrapers were displaying orange and green, trying to be as spooky as they could.

It was awesome seeing sights like the Willis Tower and Wrigley Field all over again, but now with the glow of their lights shining bright.

The lack of exterior light really woke up the interior of the train. Members of CTA’s Heritage Fleet said that Nos. 6711 and 6712 ended up going to the National Museum of Transportation near St. Louis after their retirement. Thankfully, that museum stored them indoors. When the museum sold the cars back to the CTA in 2017, they were in remarkable condition, with the CTA needing to replace only a handful of miscellaneous parts during its refurbishment program.

The windows are mostly original, as are most of the cranks used to open the them. The Illinois Railway Museum was able to provide some of the parts that were missing.

A little over two and a quarter hours after we departed Skokie, we were right back at the Dempster station. The old 6000s completed a day of tours around Chicago without skipping a beat. These trains might be 66 years old, but they rolled as strongly as anything else in the CTA fleet.

Old Trains Are The Greatest

What just blew me away was the fact that an excursion train into a city was so much fun. I expected the excursion train to feel like a normal CTA ride, but the volunteers of the Illinois Railway Museum and the CTA Heritage Fleet made it feel special. This was a ton of fun, just like other excursion trains I have taken. The only material difference is that the scenery was historic Chicago rather than cornfields or the Grand Canyon.

The excursion train did some good, too. The Illinois Railway Museum says that our tickets, which were $65 a person, will help fund the future acquisition of a pair of 2600-series ‘L’ cars when the CTA decides to retire them.

Once again, I have found deep satisfaction in taking a slow train to nowhere. That’s what these excursion trains are. You board, take a trip, and then hit reverse. You end in the same place you started. It sounds silly, but it’s amazingly romantic on top of being a rare way to experience something uncommon. If you have even a tiny interest in trains, I highly recommend signing up for an excursion train, any train. You’ll learn a ton of history and have a ton of fun doing it.

Top graphic images: Mercedes Streeter;

A new twist on the slow car driven fast.

Great article and photos, Mercedes. Seriously great photos.

The first time I went to Chicago, for work, I rented a car at O’Hare and then paid ridiculous amounts of the customer’s money parking it. Never again.

Subsequent trips to Chicago, I always took a CTA train into the city. I also got pretty decent figuring out how to get where I needed to go in NYC without a car. Sometimes there was a fair amount of walking involved in both cities. A sturdy suitcase with wheels was required. I’m much older now and will probably Uber/Lyft to save what little is left of my spine.

Chicago, San Francisco and NYC are my favorite large cities in this country. In that order. The views of the Tribune Tower across the Chicago River were stunning to west coast raised me.

I have favorite smaller cities as well. But that can wait for a more appropriate article.

Sounds like a missed opportunity to have a local breweries sponsor the train ride, and sell some $8 local Chicago pints themed to each area of the ride.