Wind turbines can be found all over the world, gracefully spinning and generating electricity to power entire communities. These structures look majestic and can feature blades hundreds of feet long. But have you ever asked yourself just how those wind turbines ended up in a big field? Getting turbines to their destination requires a concert of barges, trains, and trucks. Transporting turbines by road is a wild process involving intricate trailers designed to carry blades that sometimes match or exceed the length of some of the biggest planes in the world.

Wind power is a pretty huge deal around the world. The United States Department of Energy projects that by 2050, wind power will have a capacity of 404.25 GW across 48 states. That’s a large bump from the quoted 113.43 GW in 36 states in 2020, as noted by that same report. Of course, in order to reach that number, countless turbines need to be constructed. As technology improves, these turbines are getting larger, with their blades getting longer.

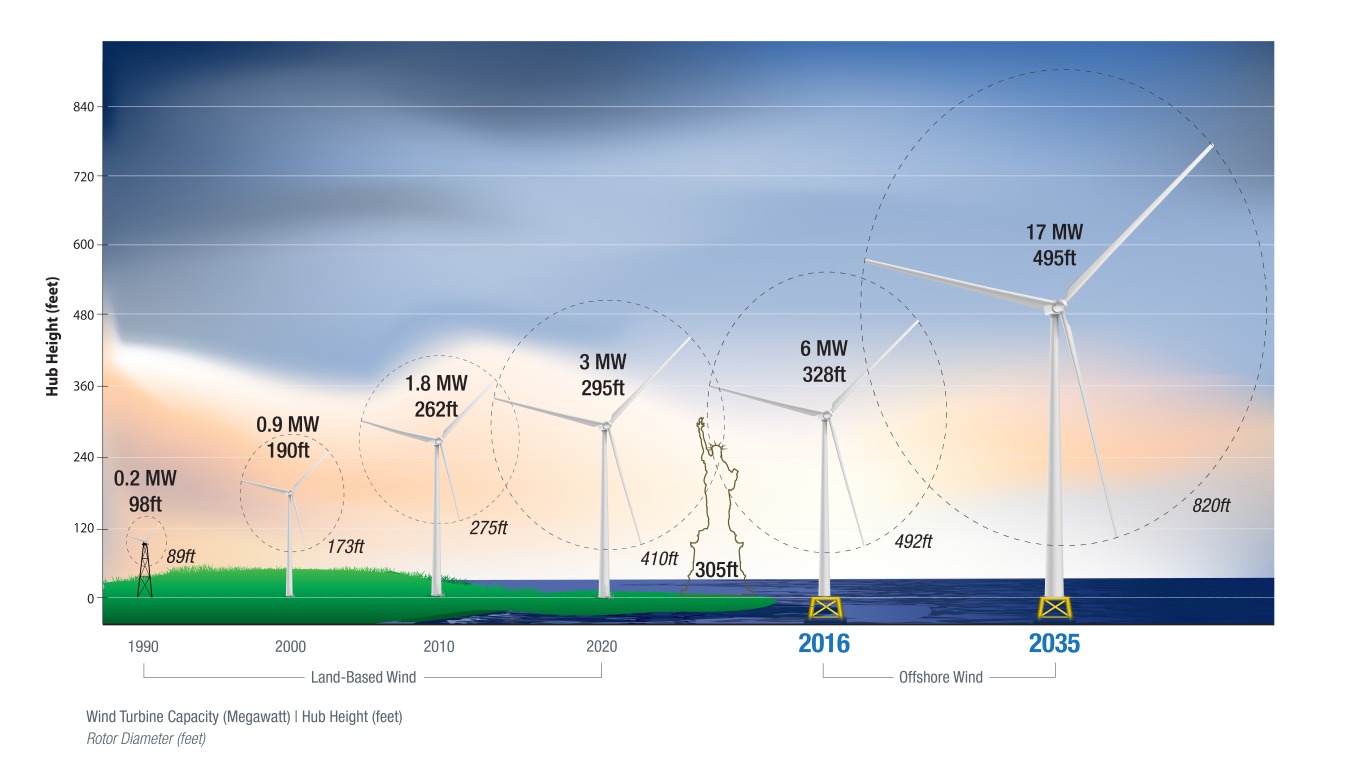

As the Department of Energy notes, larger wind turbines with longer blades are more efficient. These longer blades have larger swept areas and capture more wind. As such, it’s not at all surprising to see that companies are constructing beasts of turbines with blades over 200 feet long. The Department of Energy says that Americans have been capturing the wind for industrial use for the past 175 years. However, it took until 1980 for the first large utility-scale wind farm to be installed. In the early days, the DOE says, turbine rotor diameter was under 100 feet, translating to individual blades that were shorter than 50 feet.

These turbines were absolutely tiny compared to the monsters of today. As of 2024, the world’s largest onshore turbine blade, for the SANY SY1310A, is 430 feet long. The rotor diameter of the SANY SY1310A is over 800 feet, which is wild considering how small turbines were only 35 years ago.

The largest wind turbines are offshore units, and the biggest one on the planet stands 1,115 feet tall with a blade diameter stretching 1,107 feet. One of the reasons offshore wind turbines can be of such mammoth size is due to companies being able to ship turbine parts by water, where there are no towns to drive through, overhead lines to worry about, or bridges to dodge.

The wild thing about the SANY SY1310A that I talked about above? That’s an onshore turbine, and its parts were shipped by land. The promotional images for the turbine even show the 430-foot blades, with the long truck that hauls them looking like an ant in comparison.

By Sea Or Rail

Shipping wind turbine parts by land is a delicate process. Typically cargo gets loaded onto a truck and is driven off to its destination using the most efficient route possible. That entire concept is thrown out when it’s time to ship wind turbine parts.

According to German engineering magazine Schaeffler Tomorrow, the journey of a wind turbine often starts on a barge or a train. The Union Pacific Railroad says that shipping wind turbine parts by rail is beneficial as train cars don’t disrupt road traffic, don’t shut down cities, and there’s less bureaucratic red tape in shipping gigantic parts by rail than shipping them on the road. Likewise, the railroads already have specialized equipment to handle huge loads.

Still, Union Pacific notes, wind turbines aren’t just loaded onto normal freight trains. Instead, turbines get their own special consists (that’s a train) that take their own special routes that avoid obstacles and other hang-ups. The transportation of wind turbines by rail doesn’t sound a whole lot different than how power transformers are hauled by rail. Check out this wind turbine train in motion:

Union Pacific notes that its trains will pick up a wind turbine at the manufacturer and then roll the train to a distribution center that’s the closest to the destination wind farm. A somewhat similar concept is used for barges, where wind turbines will navigate waterways to get as close to the destination as possible. Then, trucks are used for the last-mile delivery.

Hauling The Last Miles

Freedom Heavy Hauling, a company that specializes in trucking everything from oversized construction equipment to wind turbines, has a pretty neat explainer of the mechanisms of road-based turbine transport.

The company starts off by giving you a picture of what’s going on here. A single turbine blade may measure over 250 feet in length and weigh a couple of dozen tons or more. The best comparison that I can come up with is that a Boeing 747-800 measures in at 250 feet, and there are lots of turbine blades that are longer than that. So, the trucks carrying these blades are basically trying to fit more or less the length of a widebody airliner down a road and through turns. Further complicating matters is how the diameter of a blade itself may be too tall for the blade to be transported under bridges.

Of course, while blades get the most attention, a wind turbine also consists of cylindrical tower sections and the large nacelle that sits on top. Tower sections have diameters that make them too huge to pass under bridges, while the nacelles found at the tops of turbines are hefty units that may weigh hundreds of tons. In other words, basically no part of transporting a modern large turbine is a “normal” sort of haul.

Freedom Heavy Hauling goes on to note that, because of this, route planning is critical. Teams go out and scout a route to get the turbine parts from the manufacturing facility to their destinations. As Schaeffler Tomorrow notes, this isn’t just sending some people out to drive on a road; but the team is out there to look for a route that poses the least risk.

This team is armed with the expected cornering radii of their load, and they check turns to see if their load will clear. They’ll also check for overhead power lines, street lights, signage, or anything else that may impede the progress of the haul. Freedom Heavy Hauling notes that a 53-foot turbine blade may need as much as 250 feet of room to complete a turn.

This stuff apparently gets pretty high-tech, too, with surveyors using radar to determine if the road can support the expected weight and then using mapping software to simulate the route. Freedom Heavy Hauling notes that route planning has to work around problems such as the fact that most rural bridges cannot handle the high weights of the wind turbine parts, so those areas have to be avoided. Freedom Heavy Hauling also notes that there are many old bridges in America, and that many of them, regardless of where they are, have strict axle weight limits that could be broken during a wind turbine move.

The scouts also check available data to see if there will be road construction in the area a the time of the move. Schaeffler Tomorrow notes that if crews get caught up by surprise construction, there is no turning back. The turbine is staying where it is until the pass clears.

Cutting Through Town

All of this is hard enough, but route planning also has a human element. Taking a path that excludes a town center or overhead lines may not be possible. It takes time to navigate turbine parts through city centers and other obstacles, and doing so may involve the local utility company temporarily removing overhead lines or taking down street lights. All of this takes time and may require temporary road closures and detours. Freedom Heavy Hauling says it’ll work with local authorities to find the least disruptive way to get a turbine through a town, and often, this means avoiding peak tourist seasons in towns and cities or coordinating with harvest schedules in rural areas. The company also notes that they might try to move through a city during the day, as the loud sounds of machinery may wake people up at night.

Schaeffler Tomorrow notes that, at least in Europe, if a wind turbine is being transported on a highway, that will likely happen late at night after traffic dies down. That’s why you might find turbine blades parked on the side of a highway in the middle of the day. This great video shows that even turning onto a highway can be ridiculously tight for these crews:

Then there are the permits. Freedom Heavy Hauling notes that shippers need to get permits to haul oversized and overweight freight on the road. These permits may also need to come from multiple jurisdictions, which can take between several business days to months. In all, Freedom Heavy Hauling claims, one project may require as many as 50 permits. Each jurisdiction also has its own rules on the necessary number of escorts, whether a road might need to be temporarily widened or not, and other details.

There’s even weather considerations, as winds and ice will also change how the turbine gets rolled down the road. Ice causes the trucks to lose traction, and high winds can impact stability. The turbine manufacturers also want their parts moved between certain temperature ranges to reduce the chance of damage.

It’s because of all of this that Schaeffler Tomorrow notes that no two wind turbine moves are the same. There are so many different components to just planning the move that it’s different every time.

Special Equipment

Note that I haven’t even gotten into the equipment yet!

The common trailers used to carry turbine blades seem simple. They look like regular trailers, but with a narrow spine. The reality is far cooler. That narrow spine? It’s adjustable, so that one trailer could handle blades of varying lengths. Check out this video from XL Specialized Trailers that shows how its trailers extend and retract:

These trailers also commonly have wheels that steer. XL Specialized Trailers says that its turbine blade trailer has a hydraulically operated self-steering system, which is designed to point the rear wheels in line with the kingpin at the front of the trailer. That way, a truck can swing a turbine blade around a corner more easily. There’s also a manual steering option for precision turns. Its trailer extends out 184 feet long, and then the rear bumper can pull out, adding another 20 feet.

XL Specialized Trailers is far from the only company out there with a self-steering turbine blade trailer, but it did have that neat video. These trailers haul some seriously heavy weight, too, with capacities often beyond 80,000 pounds. This video below shows how some of these trailers can lift both their load and their suspension to get around tight curves:

Another variation of this trailer idea eliminates the trailer itself and attaches a set of axles onto the blade. This isn’t the only way to ship a turbine down the road. As our Lewin wrote two years ago, there are also specialized machines capable of lifting the blade up a bit to help clear obstacles on the ground:

The transport industry built a new class of vehicle to solve this problem–the self-propelled rotor blade adapter. The Scheuerle Rotor Blade Adapter G4 is the type seen here, built by German industrial giant Transporter Industry International, or TII. Fundamentally, it looks like a giant yellow trailer with no attached semi truck. It features a single cantilever-style mount for a large turbine blade.

The end of the turbine blade is left unsupported, with no dolly at the rear. The real magic, though, is in the fact that the mount itself can pivot. This allows the blade to be raised up at an angle when required. It’s a crucial feature that makes all the difference, allowing the vehicle to get a turbine blade around a corner without clipping street signs or knocking off chimneys.

If the basic concept looks familiar, it’s essentially a self-propelled modular transporter, or SPMT, with a wind turbine mount on the back. SPMTs are used for all kinds of heavy, slow-speed hauling jobs, like moving parts of ships, oil rigs, or even shifting entire buildings. The vehicle runs on a 300 horsepower diesel engine, though it doesn’t directly drive the wheels. Instead, hydraulic motors are used to drive the wheels on a couple of the axles, providing fine control. Each axle can also be steered on its own pivot, and can be raised or lowered to keep the vehicle flat even on very uneven terrain.

What Lewin didn’t note in his piece is that SPMTs are also used to move wind turbine equipment. Remember how I said wind turbine nacelles can weigh hundreds of tons? Well, that weight often isn’t evenly distributed. The nacelles also contain somewhat delicate equipment. SPMTs have dozens of wheels and tires and are capable of spreading out the weight more evenly. The axles of SPMTs are also capable of turning 360 degrees, making them pretty decent at moving heavy equipment through tight turns.

However, as you could probably imagine just by looking at a SPMT, these things move at about 1 mph when loaded. These are really for maneuvering through tight quarters rather than a highway haul.

Nacelles may also travel on what’s called a modular trailer. These have extendable sizes, several axles, high weight capacities, and are designed for road speeds.

Supporting these trailers may be cranes and gantry systems to lift wind turbine parts and to lower them onto the trailer decks.

On The Road

Finally, once everything is together, it’s time to actually drive the load down the road. Escorts will lead the load through the route. Pilot vehicles check clearances, and the team may steer or lift the turbine parts out of the way of obstacles. The team is also constantly checking the weather, and the authorities are also doing their part, too.

Schaeffler Tomorrow spoke with Florian Dufresne, logistician with wind turbine manufacturer Senvion, and the publication notes even more hurdles:

Instead the part of the Senvion logistician is to discuss the project with all the other stakeholders, approving authorities, private highway operators and, above all, the people on the ground. At that time, he’s a diplomat first and foremost, having to alleviate the concerns of mayors and county officials that the special transports won’t cause any damage. Plus, he has to explain why the journey of the giants has to be routed through their region in particular even though the wind farm will be established at a remote location. “We can never take the shortest possible route. To cover a distance of one kilometer, the convoys often travel ten, 15 or more kilometers on the road. A bridge with a sufficient load rating may be located five kilometers farther to the east, but then an underpass that’s too low may have to be given a wide berth. So one kilometer is added to another and approvals must be obtained again and again,” explains Dufresne.

Put it all together, and what sounds like the simple act of shipping a part turns into a delicate dance. That’s why it’s not at all surprising to see wild ideas for how to get around transporting turbines by land. In theory, something like the WindRunner Radia plane that I recently wrote about would eliminate several steps in shipping turbine blades, from rail travel to trucking.

Other weird potential solutions include one from the U.S. Department of Energy’s National Renewable Energy Laboratory, which pitched the idea of making turbine blades that bend. Lockheed Martin once had a proposal to ship turbine blades via airship.

None of these weird ideas have come to fruition just yet, which means that turbines are still shipped the hard way. So, the next time that you see a turbine blade going down the highway, now you know that a ton of work was put into getting it there. Talented individuals planned that move out for weeks, got piles of permits, and then loaded it onto some special equipment. All of it so that one day, giant farms of wind turbines can produce tons of energy.

Top Image: XL Specialized Trailers

In Colorado, I saw a long parade of train cars with blades like those on UP tracks heading south from I assume Denver towards Colorado Springs. I hadn’t thought about how they got to the “last mile.” Thanks, as always!

I’m still not sure why helical windmills aren’t a better use case for this.

Where do they find that huge person with the huge hands to tighten the ratchet straps on the trailer in the XL Specialized photo?

Mercedes once again you have come up with a interesting thing to inform and entertain us.

Im not sure how you come up with these ideas but please keep up the great work.

Thank you

This really is a site with an interesting mix of minds doing individually creative and inspired work. Managing all the creators? Matt, is that you? I’ve had a similar challenge, but I’m too old for this shtuff anymore.

Used to see these all the time coming out of West Fargo, ND. Then some other company bought ’em out in the early teens and closed the plant and around 220 jobs.

Incredible transportation planning, though. I would hate to be those drivers.

Yes, blimps would possibly make more sense but then the amazing sight of an enormous thing doing this is fun.

https://www.facebook.com/bbcscotlandnews/videos/wind-turbine-blade-transported-through-scottish-borders/1069056080883480/

There are due to be twelve big ones at the top of my,,,,, garden? yard? estate!!?? Stuff will do. the planning has been a decade or more, No I live in Northumberland , not Scotland, the single track roads have been prepared, now I wait.

I remember seeing trucks driving through Texas with three turbine blades. As the windmills got larger, it was one truck for the turbine, one for the nose cone and three additional trucks carrying one blade each.

I have to believe that these blades can be made in two pieces and joined together at the point of assembly. It’s not impossible.

Just a few days ago, in the same area of I-70 where you had your misadventure with the truck, one of these blades swung loose from its carrier and blocked both sides of the Interstate.

I was wondering if this article was a result of the incident, or just odd timing.

https://www.nbcwashington.com/news/local/wind-turbine-blade-blocks-traffic-on-interstate-70-near-hagerstown/3947054/

A use-case for blimps?

300GW of wind in 30 years sounds relatively impressive until you realise that China installed 46GW of wind so far in 2025 and a further 198GW of solar.

Another well written, researched and thought-out article Mercedes.

Numbers like that from other countries, from both renewable energy implementation and EV adoption, reinforce just how badly we’ve fallen behind as a nation. We’ve allowed legacy business matters to call the shots, and reduce innovation. This is how great nations die.

Great nations also die when they concern themselves more with who is in the bedroom rather than do you have forward thinking people in the boardroom. Death also comes in the thousand cuts of quarterly earnings reports and the accounting antics therein.

Sounds like a job for a blimp.

Sorry this is small potatoes compared to the transportation of blades where I live. We have many wind turbines near us but very few roads that are wider than two lanes. They just recently added two feet of asphalt to make roads two lanes to import replacement blades. If you want I will see if I can video these blades being transported in a small town where the speed limit is 25 and every intersection is a light or stop sign

Oh yeah? well where I live I once had a car transporter give up 3/4 miles away from my place after doing 1500 miles! 🙂 (delivering a car right by Wriggly field in the middle of a Cubs game wasn’t good timing on either of our parts. Despite the game it was a full length Kenworth sleeper and a full length articulating double deck car hauler. I’m impressed he made it as far as he did)

Some of the images in this article are definitely older because those are much smaller blades than what is being produced these days. The industry has really shifted to the larger sizes simply because it is so much more cost effective – a nominal bump in price for a larger blade can produce a lot more power.

Indeed, some of those are older images! Sadly, we have to work with images the least likely to piss off the wrong entity. 🙂

I once got caught directly behind a rig not quite as big as this but still a two part turbine trailer on I-40 heading west right as we started crossing the Appalachian mountains. It was frustratingly long and slow way to watch something that was amazing. At one point I seriously debated driving under and around the thing in a turn, but I also knew some really complicated stuff was about to happen and wanted to just watch and see what happens next.

At some point I’d have taken the next exit and looked for an alternate route.

We passed a half-dozen of these trailers in New Mexico and Texas on a road trip last month. My nerd brain lost it watching these navigate the pass outside of Albuquerque, taking up several lanes going around corners. Looks like the commentary is already gone sideways, but thanks for deep diving into these cool things.

Yeah! We may have seen the same ones. It felt like I couldn’t go down 40 without seeing at least one blade last month. Imagining them going through the canyon East of Albuquerque is fascinating. Wouldn’t want to be stuck behind them.

The county I work in has several wind farms. One just started getting built up 4 years ago. In the past I would leave for work 10 minutes earlier just in case the highway was held up as was the case when a blade carrying truck had to make a turn onto a county road. Haven’t seen much activity recently but did spot one of those survey vehicles last week. After reading the last article, I’ve been daydreaming about seeing a WindRunner plane coming in for a landing in the country while driving to work.

They are pretty but a colossal waste of taxpayer money, just like Tesla EV subsidies.

I agree with you on the EV subsidies, to a point. EV subsidies are also easy to understand in the form of tax rebates and CAFE credits that benefit Tesla, for example. But I’m wondering if you really have any idea about subsidies for wind energy. This kind of opinion is usually unsupported by facts. An opinion or belief that is not backed up with cold hard facts is worthless.

Not for long. Didn’t you hear? The Big Bad for America Bill passed. It completely destroys the renewable energy sector. And I thought Trump wanted domestic manufacturing jobs. Guessing the oil/gas industry bribed him better than the renewable sector. Don’t even talk about EVs.

I hate that this is the first comment on yet another great article from Mercedes, but I have to confess my mind immediately went here too. Not in a good mood today.

Big Wind should have pitched: look how much gas is used for the trucks and trains hauling the parts around. more wind farms = more gas is needed