Most locomotives and their carriages serve out lengthy careers stretching decades. Depending on where you live, the trains that ran commuter rail when you were a kid might still be on the rails today. That wasn’t the case for the Fyra rail service that ran between the Netherlands and Belgium. The service used an Italian-built train that was so unreliable and so chronically late that the trains were pulled from use after only six weeks. What followed was an embarrassing scandal that grew so huge, even a German grocery store got caught up in it.

There’s a pretty good chance that, if you need to travel a long distance in America, you’re likely to fly or drive. Bus travel and train travel are still around, but most of America’s passenger trains are relatively slow, and plane tickets are sometimes cheaper than bus tickets. America does have trains that can travel at the blistering speed of 160 mph, but you’ll find them in only one region along one route.

The state of high-speed rail is completely different in Europe. If you need to take a hop between two nearby cities, Europe’s trains are so fast and so efficient that they beat planes to some destinations. Sure, planes fly faster than trains, but taking the train doesn’t require you to commute to an airport, go through a security line, or wait at a gate.

Trains are so hot in Europe that airlines use aggressively low fares to compete. Yet, trains are still a seemingly unstoppable force in Europe, and for some, there’s even some shame in flying when a train could do the same trip in about the same amount of time. As trains surge in popularity, there have even been calls to reduce air travel on routes that could be served by rail.

Europe projects that its already impressive high-speed rail network will only grow, connecting more cities together in even faster times. To put this into numbers, the European Union says that in 2024, 443 billion passenger-kilometres were performed by rail. This represents a decade of steady growth, interrupted only by the COVID-19 pandemic and a slow ramp-up after.

All of this is to say that Europe takes its trains very seriously, and failure isn’t really an option. But failure was exactly what happened to the infamous Nederlandse Spoorwegen (NS – Dutch Railways) and KLM Fyra high-speed rail service in 2013. The line launched in December 2012, and only six weeks later, the trains were so broken and so late that NS had to pull the plug, creating a scandal that spread across nations. Things got so crazy that supermarket chain Aldi got caught in the crossfire, and the trains were even banned in Belgium.

The High-Speed Dreams Of The Netherlands

As Railway Technology writes, the Netherlands suffered from an infrastructure problem in the late 1990s. Heavy congestion in the Randstad region and at Amsterdam Airport Schiphol increased travel times. The Dutch government already had an idea for a fix. According to the AFP News Agency, in 1993, the government wanted to build a high-speed rail line that would rival the best from Germany and France.

A new rail line, the HSL-Zuid (High-Speed Line South) was approved in 1997 to decrease travel times and connect Amsterdam to Brussels via Schiphol, Rotterdam, and Breda. HSL-Zuid is a dedicated 78-mile line and accommodates the European high-speed rail network.

The route was reportedly finalized in 1998, and in 1999, the Dutch government handed the contracts to design and build the HSL-Zuid to Infraspeed BV, a consortium consisting of BAM/NBM, Charterhouse Project Equity Investment, Fluor Daniel, Innisfree, and Siemens. A banking consortium of Bayerische Hypo-und Vereinsbank, Dexia Public Finance Bank, ING, KBC, KfW, and Rabobank provided funding through a public-private partnership scheme. Construction began in 2000 with a target to have the line open by 2006 with a running speed of 186 mph.

A joint venture between NS and airline KLM put in a bid to be able to use the HSL-Zuid line and won. There was only one issue, as NS didn’t have trains to run on the line. In 2004, Railway Gazette International wrote, NS and the Belgian National Railways (SNCB) inked a deal with Italian rolling stock builder AnsaldoBreda for 12 eight-car high-speed trains with an option to buy 14 more. The order would ultimately increase to 19 trains in total, with 16 going to NS and three more to SNCB.

AnsaldoBreda was formed in 2001 with the merger of two famed Italian brands, AnsaldoTrasporti and Breda Costruzioni Ferroviarie. Ansaldo had been around since 1853, and its specialty was railroad locomotives and rolling stock. Breda had been around since 1886, and it was known for electric trains. The two firms were merged in 2001 as they were burning cash. Post-merger, the companies fell under the umbrella of Finmeccanica, a state-run entity.

Ambitious Goals

When the trains were ordered in 2004, specifications called for them to run on 1.5 kV in the Netherlands, 3 kV DC in Belgium, and 25 kV 50Hz on the HSL-Zuid line. The eight-car single-deck trains, which would also replace existing rolling stock that ran between Amsterdam and Brussels, were to be 656-feet-long, have four powered cars, and have a continuous output of 7,241 horsepower. The trains would also seat 139 first-class passengers, 409 second-class passengers, and would be designed with help from Pininfarina. All of this was scheduled to launch in 2006, right on time for the new line to open.

The projected benefits of the line were grand. NS predicted that a train from Amsterdam to Rotterdam would take only 36 minutes to complete the trip, a large reduction from the then-current time of 1 hour and 3 minutes. Other stops saw similarly great projected time reductions. NS said that a trip to Paris would see its time reduced from 4 hours and 9 minutes to 3 hours and 13 minutes.

Unfortunately, the projects, both the rail line construction and NS’s train, were fraught with delays. One cause for delay was the 4.5-mile Leiderdorp-Hazerswoude tunnel. This was an ambitious engineering project all on its own and required the use of what was then the world’s largest tunnel boring machine, the Aurora. The machine was a 393-foot-long, 48-foot-diameter, and 3,300 metric ton beast. Other causes for the delays were attributed to cost overruns, other engineering challenges like viaducts and tunnels, and signaling upgrades.

NS had its own headache to worry about, as AnsaldoBreda failed to meet the 2006 deadline, pushing the launch of its trains to 2007 and then to 2009. NS wanted to run some other trains on the HSL-Zuid line in the interim, but since that project wasn’t finished either, that option was no longer on the table.

As the Railway Gazette reported, by 2009, the NS-KLM joint venture was in trouble as it still didn’t have its AnsaldoBreda trains, and the HSL-Zuid line wasn’t open yet, either. Yet, NS and KLM had to front €148 million a year for a line they weren’t making a single dollar on.

There was finally light at the end of the tunnel later in 2009 when the HSL-Zuid line opened, and NS finally started receiving its AnsaldoBreda V250 prototype trains. NS said the trains would enter revenue service in 2010 as the Fyra service. The service would end up being delayed yet again, this time thanks to the implementation of ECTS (European Train Control System) Level 2 railway signaling system. The signaling system was finally certified in 2011, and NS finally prepared the Fyra service for launch in 2012.

In hindsight, all of the problems that led up to this point probably foreshadowed what happened next.

The Trains Were Immediately Problematic

Finally, after years of delays, the Fyra service went online on December 9, 2012. The production Fyra trains, known as the AnsaldoBreda V250, nailed the desired specifications, at least on paper. The V250 trains consisted of eight car sets measuring 659 feet long. The trains, which weighed 485 tons when loaded, had carriages made of aluminum, leading units made out of steel, and were propelled with asynchronous motors, adding up to 7,400 HP. Tractive effort was 292,251 lbf. The trains also had the desired capacity, fitting 546 passengers in a two-class configuration.

As the Financial Times reports, NS ordered 16 trains and had received nine sets by the opening of the Fyra service. This cost NS €21 million per trainset. At first, it seemed like NS got a killer deal. AnsaldoBreda offered NS trains with a 155 mph top speed for less money than the Alstom (the makers of the iconic French TGV) and the Siemens (the makers of Germany’s ICE trains) competition. The trains even had a sleek design with inputs from Pininfarina, giving the Dutch a train they could be proud of. Smart, right?

Unfortunately, the trains were a disaster right from the start. Here’s what the AFP News Agency wrote about the train on June 8, 2013:

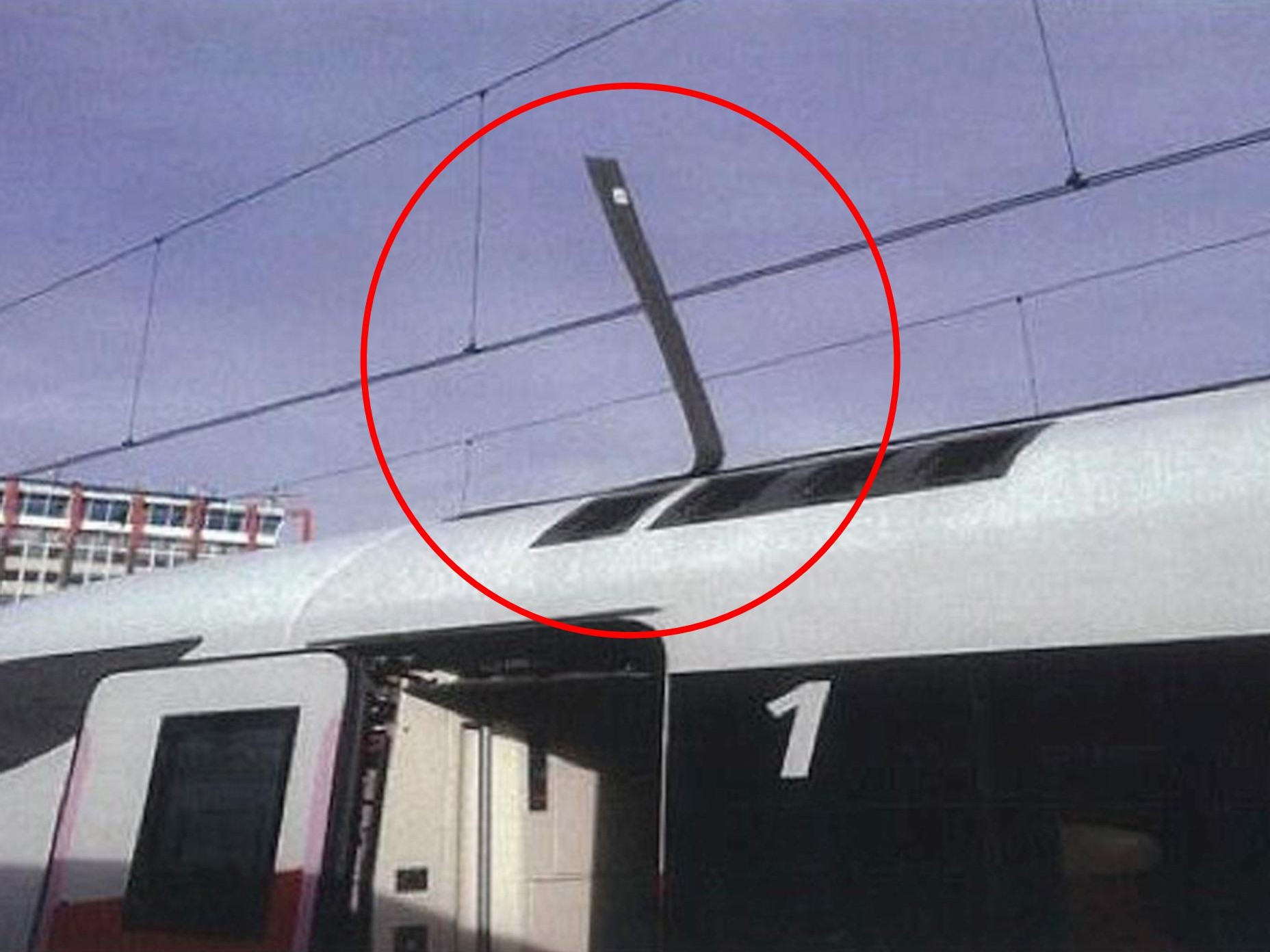

Results of a Belgian investigation, published extensively in the Dutch press, uncovered software and braking problems, loosening doors, pieces of metal strip peeling off the roof, damage to hydraulic and electrical cables and rust after only a few kilometres on the tracks. The last straw came with the discovery of a metal bottom plate next to the tracks which fell off a passing Fyra, prompting NS to suspend the service and launch a full-scale investigation.

Based on its own probe, “the NS has come to the conclusion that continuing with the V250 would be irresponsible and not desirable for travellers,” it said. On Friday, the Dutch government backed the state-owned NS’s decision with Deputy Prime Minister Lodewijk Asscher saying “we cannot conclude differently than the NS.”

[…]

The Dutch government thought it had gotten a bargain when AnsaldoBreda offered to deliver 16 Fyra trains at 20 million euros ($26 million) a piece by 2007, to be ready to put in service by 2009. “They wanted cheap rolling stock” and selected a manufacturer “without any proven knowledge of building high-speed trains,” [Rob Goverde, a rail expert at Delft’s Technical University] said.

The trains suffered high-profile failures during their short stint. According to the Financial Times, the trains’ undercarriages were damaged when running in snowy and icy weather, and software faults would leave them stranded at stations in the cold of winter. NS had to compensate with domestic trains and buses. The BBC‘s report on January 22, 2013, was shocking:

During the first week of service, malfunctions left passengers stranded at various stops along the route, forcing some to switch to buses, Reuters news agency notes.

Last week’s wintry weather saw the problems get even worse and the trains were taken out of service. “It was a tragedy, hallucinatory,” Belgian rail chief Marc Descheemaecker told Belgian broadcaster VRT. Those trains – pieces went flying. Doors didn’t open. Doors didn’t close. The steps didn’t work.”

The Belgian operator, NMBS, suspended its 63m euro (£53m; $84m) contract for three V250s on Monday, giving AnsaldoBreda three months to fix the problems or face legal action for damages.

The BBC would go on to note that the V250s were so unreliable that they would make other, unrelated trains late by being stranded at stations.

If the constant malfunctions weren’t bad enough, the train’s performance was worse. According to HLN news, when the Fyra service launched, 5.6 percent of the V250 trains never reached their destinations due to breakdowns. Worse, fewer than 55 percent of the trains reached their destinations on time, and 20 percent of the trains experienced delays exceeding 15 minutes in length. In other words, there was a good chance that if you boarded a Fyra V250, you would not reach your destination, you would be forced to stand in the cold, or you would get there late.

Somehow, it got worse. As the AFP notes, parts fell off these trains, including a bottom plate and a hood from a cab car. According to Belgian broadcaster VRT news, Belgian authorities responded to the discovery of the fallen parts by suspending the V250 train service in the country, effectively banning it.

An Investigation

Dutch and Belgian authorities then commissioned a third-party investigation into the trains from consultancy Mott MacDonald. The discoveries were numerous. The investigation found loose parts, parts that fell off, heavy corrosion, dangerous mechanisms that were not protected from passengers, and areas of poor execution. For one example, the investigation found that the train’s horns were susceptible to snow buildup.

From the investigation:

“Cable routings, pipework and cable retention methods when connecting from the underframe to individual pieces of equipment are often executed in a poor and haphazard manner which presents numerous opportunities for snagging, wearing and damage. Such practices would not be expected from a competent international rolling stock manufacturer. Numerous methods have been employed by AnsaldoBreda to either protect vulnerable cabling and pipework, or to restrain such installations. Methods used vary from trainset to trainset and generally lack both robustness and elegance of execution. Even with additional protection advanced wearing has already occurred to the additional protection in certain places.”

[…]

“The vehicle end structure (up to and below coupler level) is not robust and is flawed in many aspects of its design considering its vulnerability to impact and damage. It is not considered to be suitable for long term operations.”

[…]

“While no single issue is likely to have a significant reliability implication on its own, the large volume of small problems is likely to lead to reliability issues in the future. The quantity is too large for a practical inspection regime to be implemented in the medium to long term.”

The report continues on like this for 50 pages and even documents an instance when a carriage’s batteries caught themselves on fire. Mind you, all of this happened while the trains were still new. The Mott MacDonald report concluded that fixing all of the flaws would take crews between 17 months and two years to fix, with NS fronting the cost.

Authorities also got a second opinion from consultancy Concept Risk. According to Rail Journal, Concept Risk also expressed concerns about the V250’s design.

The Aftermath

Fyra service ended on January 17, 2013, roughly only six weeks after the trains entered revenue service. Following the investigations, the Dutch and Belgian authorities demanded the return of the trains to the manufacturer and a refund. Initially, AnsaldoBreda pushed back, claiming that at least some of the problems observed were because of the railways running the trains at 155 mph in the snow.

The Dutch government canceled the €336 million contract it had with AnsaldoBreda, and then demanded that €40 million be returned for trains it had paid for in advance. Meanwhile, AnsaldoBreda sued the railways for breach of contract and for payment on the remaining trains. In 2014, the parties reached a settlement, with the trains sent back to AnsaldoBreda and NS getting paid €125 million, or €88 million less than what NS paid for the trains. An additional component was that if the returned trains were resold, NS was able to earn up to €21 million in compensation for each train.

The very public failure of the V250 trains led to some interesting public reactions. Dutch tabloid AD reported that some people in Belgium referred to the V250 as the “Aldi train,” making a reference to the cheap goods found in Aldi grocery stores. Reportedly, Aldi pushed back on this, saying that its products are low-cost but high-quality. Allegedly, some online might have referred to the train as the spaghetti-boemel, or “spaghetti slow train.”

Some online chatter from the period does suggest that some Belgians really did refer to the V250 as the Aldi train. That’s amazing. People hated the train so much that a grocery store that had no part in the blunder caught some strays. As for the V250s, their stories didn’t end here. In 2017, Italy began running the V250s on its Trenitalia lines. Meanwhile, NS canceled the Fyra brand due to its poor reputation, and Thalys trains took over services from Amsterdam to Brussels.

This story is one that sounds crazy enough for Hollywood. Here we have two nations wanting to build a high-speed rail network, bought trains from the lowest bidder, and the trains failed so hard that they lasted only 39 days. It’s like something out of a comedy – though I reckon this didn’t seem that funny to the travelers who had to stand in the cold because of yet another broken train.

Thankfully, such fails are generally rare. Every day, millions of people all over the world board trains confident they will get to their destinations safely and on time. Transportation has evolved, learned from mistakes, and has gotten better over time. But every once in a while, a series of unfortunate events unfolds, and you get a blunder like the Fyra.

Top graphic image: Arnold de Vries / Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Gotta say, a failure of pretty spectacular proportions. Even more interesting for me as my (Polish) government will be soon buying high-speed trains and we’re sure to see some comments saying “why are we buying Siemens/Alstom/<something else with established brand> instead of developing our own.”

Speaking of our own, yesterday was a nice round 20th anniversary of a pretty spectacular thing that happened on Polish tracks. One regional train was used, in passenger traffic, to stop another one (where brakes failed due to a defective design). Look no further if you want to write an interesting article on the topic: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2005_Świnna_rail_crash.

As a Brit, I’m shocked that any other country even gets close to beating our record of absolutely fucking up rail travel. For example.

Note that it was Italian companies that got the APT concept working and sold it back to the UK.

Breda made some of the DC Metro cars—with the dubious honor of making the only trainsets that didn’t get a refurbishment program to extend their life since they were so unreliable. Instead the 4000 series cars were replaced ASAP when new trainsets (the 6000 and 7000 series) became available. Even the 1000 series, which literally killed people, saw longer use.

South Africa and a Spanish train maker, managed to make trains which were too tall for the South African railway system — amid allegations of terrible corruption in the ordering process. Case still ongoing.

Then in France some genius ordered trains which, while fine for Paris railway stations, did not fit anywhere else in the country. Took a year building work to widen platforms before they could be used…

AnsaldoBreda is the railway equivalent of Dodge Volare…

The Danish Railway (DSB) ordered 82 units of IC4 from AnsaldoBreda to replace most of diesel-powered IC3. The teething issues with IC4 were too much and too frequent for DSB, and they were pulled from the service many times. DSB leased the ICE-TD (originally retired much earlier due to higher than anticipated operating cost) from Deutsche Bahn and pressed most of reitred IC3 back into service for a while.

Breda had a very notorious reputation in San Francisco when its LRV2 and LRV3 broke down or had numerous mechanical issues many times in the late 1990s while Boeing Vertol was falling apart and leaving the parts on the tracks in their wake. Both were very heavier and more expensive than Boeing Vertol, leading to intense complaint about the noise and vibration. The LRV2 and LRV3 were so unreliable that MUNI replaced all of them by 2023 and 2025 respectively with new LRV4 from Siemens.

Who in right mind would want to keep buying trains and carriages from AnsaldoBreda given its much-maligned reputation is beyond me…

FYRA: fix your railroad Anthony

Ah… the Fyra. Never understood the branding of why what supposedly was a reference to the Dutch word for proud (fier) they took the Swedish word for four! I lived in Utrecht during the whole HS line construction and Fyra funfest. Worked in Den Hague region and office outside of Brussels. NS Intercity to either Amsterdam Centraal, or to Rotterdam Centraal to then connect with Thalys.(depending on best connection) I never rode the Fyra, we booked tickets, but for a trip scheduled after train itself was cancelled. Colleague rode it and described the trip as pretty good, though they were on one of the few trips that actually went according to plan. Thalys OTH, is mostly smooth and fast service (except one time when we were delayed thanks to a cow on the tracks!)

Great article. Thanks!

What a hilarious read. I would have sworn that the headline picture was AI or some wonderful photoshop. I was wrong.

My question is how the hell did that thing run 155mph with the coupler and front end looking totally exposed. Seems like a rather drag inducing set up there

There’s interesting story threaded through these umpteen thousands words worth of dry facts, but I didn’t have time to find much of it. This tale is presented at such dense level of detail that would take a trainspotter (UK) or a foamer (US) to absorb. An old writers’ saying goes that I wrote you 5000 words because I didn’t have the extra time it would take to write it in 500. I could write that more succinctly if I took more time, which is the point here.

Perhaps our dear Mercedes writeth too much? I can barely keep up, and I’m a fast reader who’s done with my New Yorker mag by midweek. I have to wonder how she cranks out so much copy every day, while having transit-liked misadventures from cost to coast. Might there be some cut-and-paste involved? The persistent use of the British term “carriages” instead of coaches or cars makes me think so.

In short, I don’t want to know every detail of this snafu. I would like more of the “who” and the “why” of it, though…

It’s deeply unkind and reckless to casually speculate that a writer might be plagiarizing.

I can guarantee Mercedes read 10x as much as she wrote and, given it’s all Eurocentric sources, she probably saw “carriage” 100 times.

She writes a lot of stories like this that are “evergreen” — just as relevant today as they will be in a month or a year. It’s possible there are a bunch in the hopper or they get used on days when they are light on content etc etc.

Maybe have some curiosity? I’ve wondered too how she has the time to do all this research. The difference is I don’t assume the answer is she must be plagiarizing, and I certainly don’t say it aloud to others if I don’t have proof to back it up.

Touting you skill in reading the New Yorker only hurts your ‘argument’. That is because even the most in depth articles by any Autopian authors read really well, and write about topics that are not available anywhere.

I feel the ‘bread and butter’ of The Autopian is long form articles. It’s why I am a subscriber.

Did anyone else see Fyra and immediately think Fyre Festival?

Breda should have been able to do better since they built the Settebello trains in the 50s

Front end of that train looks like an early 2000’s FIAT Multipla. Had one as a rental in Israel 25 years ago. If looks are indicative of what is under the skin of that train as they were with the Multipla, I can connot understand why it had its issues????