The 1980s were a wild time to be a fan of Japanese motorcycles. All four of the nation’s big motorcycle brands were going all-out to make middleweight motorcycles perform like larger, more powerful bikes through turbocharging. Every brand took a different route to get there, and, weirdly, the whole fad came and went in only a few years. Kawasaki was the last of the Japanese big brands to get into the turbo game, and it came swinging. Here’s how the Kawasaki ZX750-E1 became nearly the fastest thing on the road.

We have finally reached the end of my series on this weird period in Japanese motorcycle history. Turbocharging is a rarity in the motorcycling world. Most motorcycles are naturally aspirated, and the few that are boosted today are marvels of engineering. Yet, for just a tiny period in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, it seemed as if forced induction was the future of motorcycles.

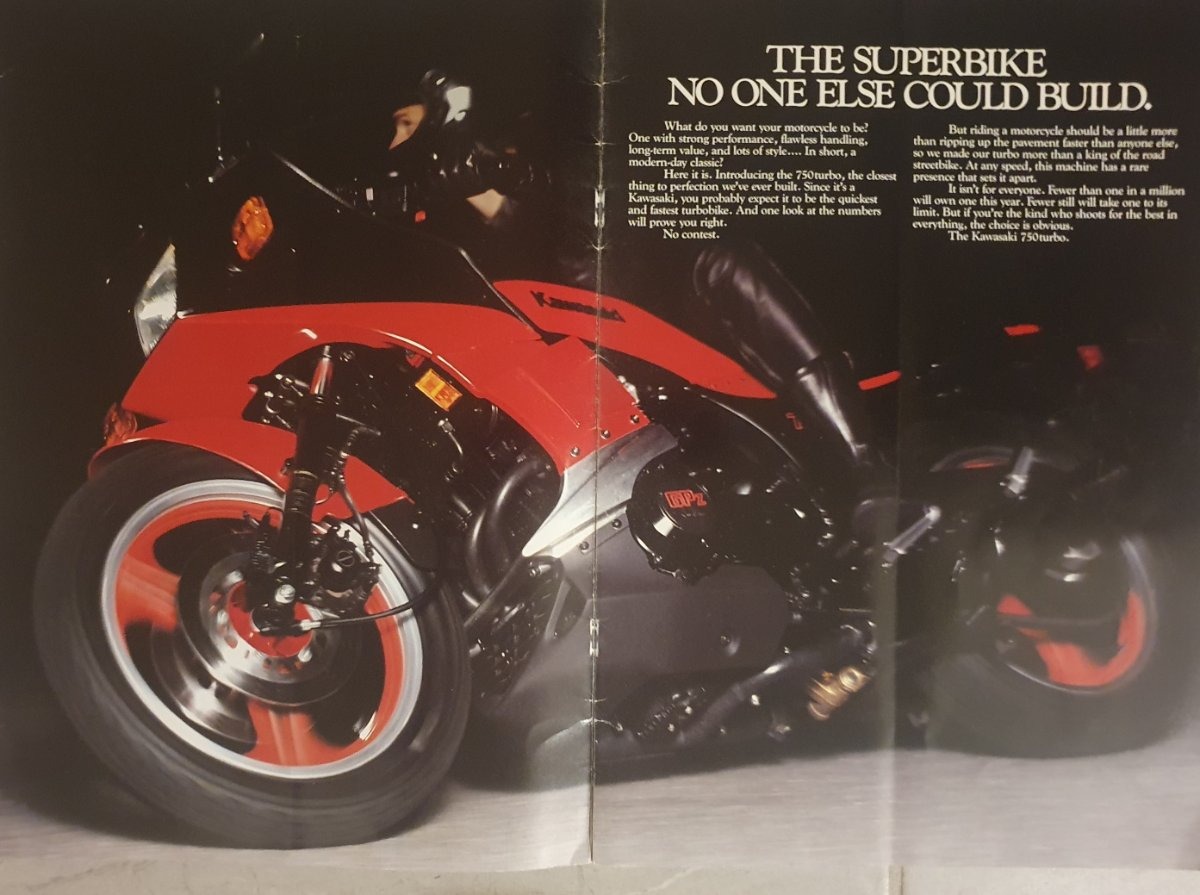

While a modified Kawasaki motorcycle was the first “production” turbo bike in Japan, it wasn’t an official effort by Team Green. Instead, Kawasaki’s official factory turbo bike arrived as the last to enter the market in 1983, right on time for the boosted bike trend to die. But it did not end with a whimper; being late to the party allowed Kawasaki to make what some still consider to be the greatest of the classic Japanese turbo motorcycles. The Kawasaki ZX750-E1 wasn’t just a more powerful 750; it was so quick and so fast that some journalists (and Kawasaki itself) thought it was the fastest thing on two wheels that you could screw a license plate onto. Kawasaki did it through clever engineering.

Last, But Not Least

According to a 1983 issue of Cycle News, Kawasaki officially kicked off its turbo motorcycle development program in 1980. At first, Kawasaki engineers followed a similar path to the ones the competition’s slide-rule guys had blazed. The Kawasaki effort was based on a 650cc-class bike and, like most of the other brands, Kawasaki was going for power.

However, the gestation period for the new Kawasaki turbo bike was so long that the engineers got to see what Honda, Suzuki, Turbo Cycle, and Yamaha did right and did wrong before finalizing their own turbo plans. They realized that everyone else made wickedly quick bikes, sure, but they only matched the power of a 1000cc engine or perhaps eked out a little more. Most buyers didn’t see the point in buying a far more complex motorcycle for the same price as a literbike just to get the same performance. Kawasaki knew that if it were to be the king of the turbos, it had to go hard.

This sent the engineers back to the drawing board, where they canned the 650 idea and bumped displacement up to 738cc. This decision meant that the Kawasaki ZX750-E1 would have the biggest engine of the four official production turbo motorcycles to come from Japan’s bike makers in the 1980s.

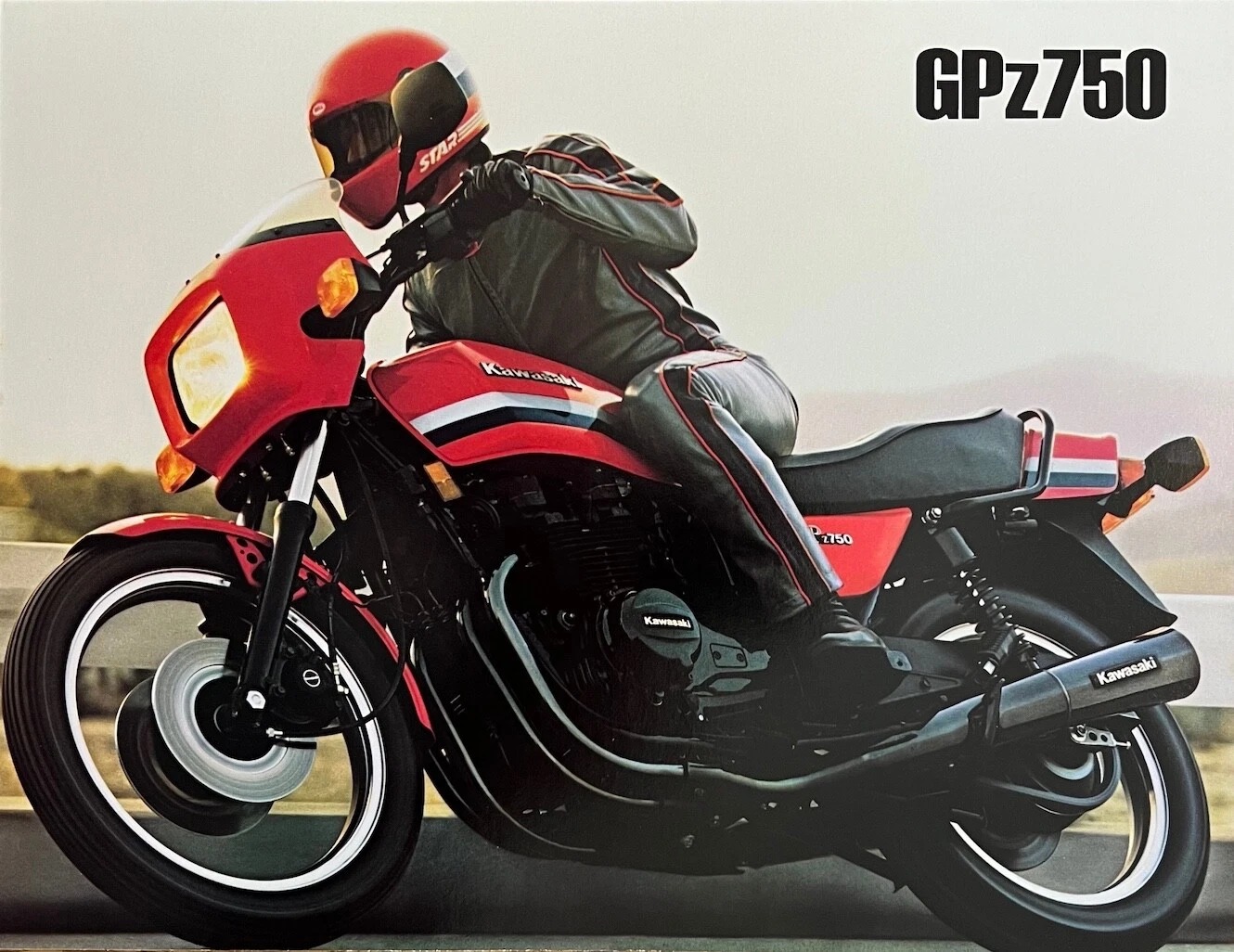

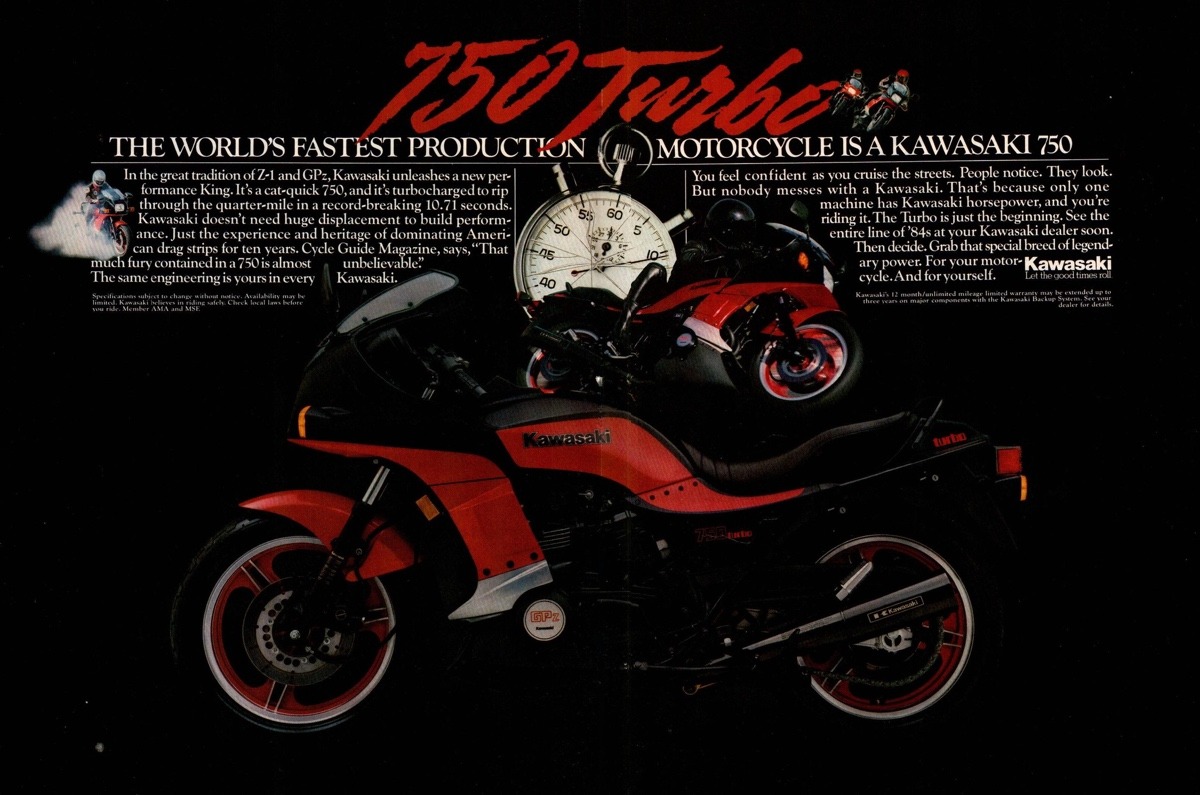

Kawasaki based the ZX750-E1, which was also advertised as just the “750 Turbo,” on the GPz750. Amusingly, the turbo bike is also sometimes called the GPz750 Turbo because the bike’s fairings still said GPz on them. The GPz750 is the sport version of the KZ750, which was hailed as the performance king in its class when journalists tested it in 1980.

Creating A Legend

According to Rider Magazine, Kawasaki head engineer Ben Inamura watched the 1969 Honda CB750 launch and capture the hearts of riders around the world. He was already working on the antidote, which launched in 1972 as the Kawasaki Z1. Then Ben crafted the 1977 KZ650/4, a 652cc motorcycle designed to have the power of a 750cc and the nimble handling of a 500cc for a price that was cheaper than any four-cylinder 750.

The KZ650 was a hit, but only for a couple of years. A new trend emerged in motorcycling as companies produced 750s and riders scooped them up. Sure, the KZ650 was designed to offer the punch of a 750, but it was still a hundred cubes short of what was popular. So, Ben would return to the lab, where he decided to scale the KZ650 up into a bigger, even faster bike.

Saying the KZ750 was a scaled-up KZ650 wasn’t an exaggeration. Ben didn’t grab a new frame or start or spread a fresh sheet of paper across his drafting table. Instead, he bored the 650’s cylinders out to 66mm and kept the 54mm stroke. The result was 738cc of displacement. The new engine still used the 650’s two-valve heads, but with exhaust valves that were a millimeter larger. In keeping with the times and the era’s concerns for the environment, Kawasaki also designed the engine to be easier on the emissions side than the 650 it was born from.

The KZ750 was a work of mechanical art. At 491 pounds, the KZ750 was the lightest 750 on the market in its day. Cycle World then raced one down the strip, closing the quarter mile in 12.26 seconds at 107.78 mph, making it the fastest 750 the magazine had ever tested at that time.

The GPz750, which made its debut in 1982, was the KZ750 but with some extra juice. To create the GPz750, Kawasaki gave the KZ750 a sport fairing, a larger gas tank, and blacked out the engine and its pipes. Engineers backed up the racy cosmetic changes with tweaks to everything from the carburetors and the air filter to the valves and combustion chambers.

The result was 80 HP at 9,500 RPM and 48.5 lb-ft of torque at 7,500 RPM – a mild improvement over the KZ750, which made 75 HP at 9,000 RPM and 46.3 lb-ft of torque at 7,500 RPM. Changes were made to lighten the bike including an aluminum brake pedal and handlebars, a plastic seat base, two fewer engine mounts, and a smaller brake cylinder. A new digital tach saved weight by eliminating the traditional cable-driven mechanical bits. However, the GPz 750’s LCD gauges, the sport fairing, rectangular headlight, twin horns, oil cooler, frame bracing, larger fuel tank, and elongated swingarm added weight back on. Still, it would have been heavier had Kawasaki not added the lightweight bits.

The GPz750 weighed just 15 pounds more than a KZ750 and carried 1.1 more gallons of fuel (5.7 gallons total) to boot. On the track, Cycle World said the GPz750 ran the quarter in 11.93 seconds at 109.62 mph. It was definitely the fastest 750 tested, and by a pretty wide margin. Unfortunately, Cycle World looked over the engine and found that someone ported and polished the intake, which the publication believed would have been responsible for a 0.15-second to 0.20-second quicker time. Even if you add 0.20 to the quarter-mile time, it was still the fastest 750 tested by Cycle World at the time.

Perfecting Perfection

So, it sounded like Kawasaki somehow made the KZ750 even better. Where do you go from there? How do you best yourself for a third time? You add a turbo!

Moving the turbo bike project to a larger engine was a strategic move by Kawasaki. One of the problems with other turbo bikes was that, due to higher exhaust backpressure at low engine speeds, other turbo bikes were slower than naturally aspirated bikes when not in boost. In choosing a larger engine to start, Kawasaki wanted to ensure there would still be enough power when the turbo wasn’t in boost.

Kawasaki’s engineers then wanted to tackle the issue with the era’s high turbo boost thresholds. One of the problems with mounting a car turbo to a motorcycle was that the exhaust coming out of the small motorcycle engine couldn’t spin the turbine fast enough until the very end of the rev range.

The production turbo bikes fixed this somewhat by utilizing smaller, purpose-built turbos. However, their boost still came on somewhat late. Riders often had to wait until their tachs reached 5,000 RPM or higher before they got action. Then, the boost kicked in, and they found themselves looking like Slim Pickens excitedly riding a bomb. This gave other turbo bikes a reputation for having a split personality, and it was almost as if you bought two bikes in one, and one of them was slow.

The engineering team noticed that the other turbo bikes in the field had their metal snails behind the engine, requiring piping long enough that the turbo response time was increased. Kawasaki’s solution was to slap the turbo right on the front, from Cycle World:

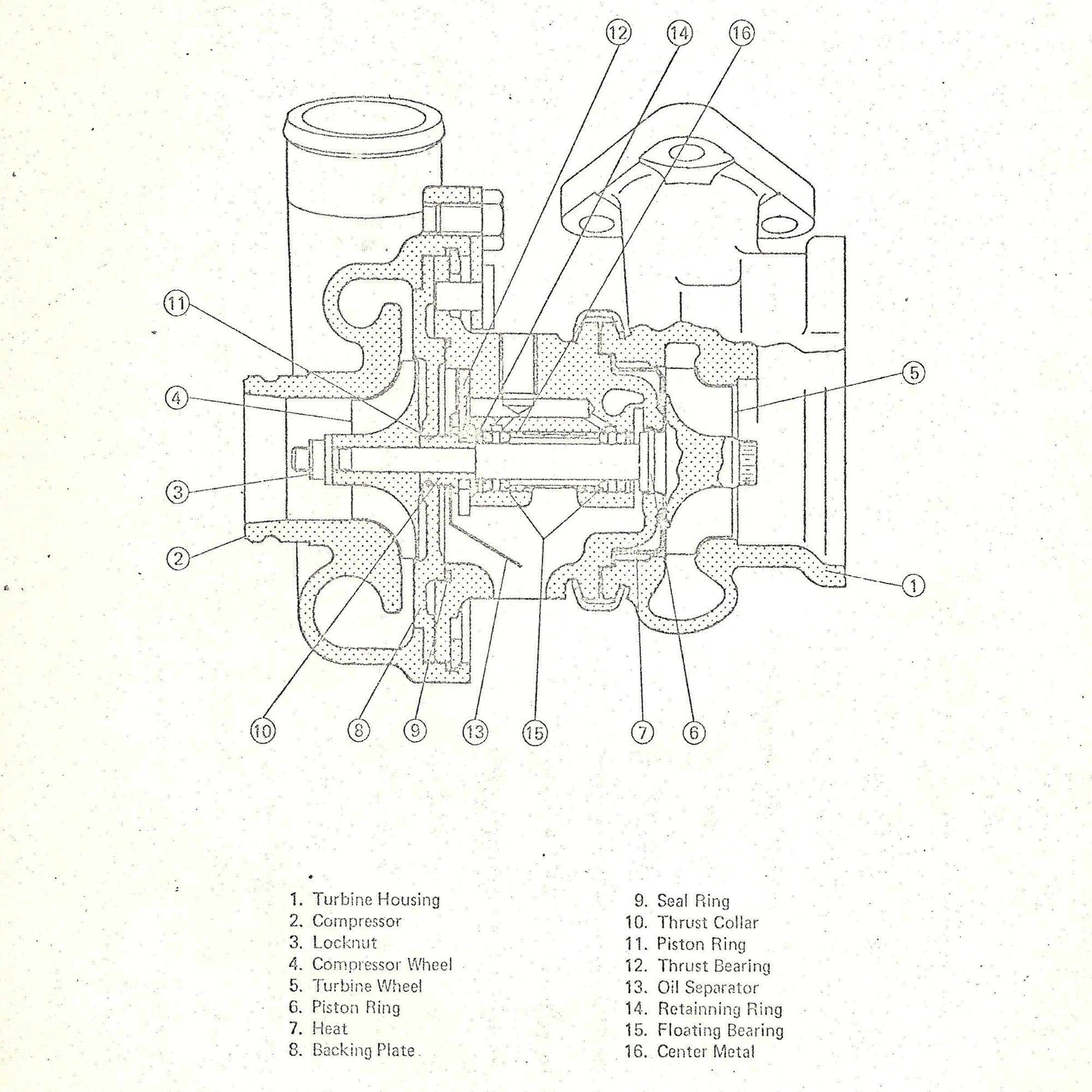

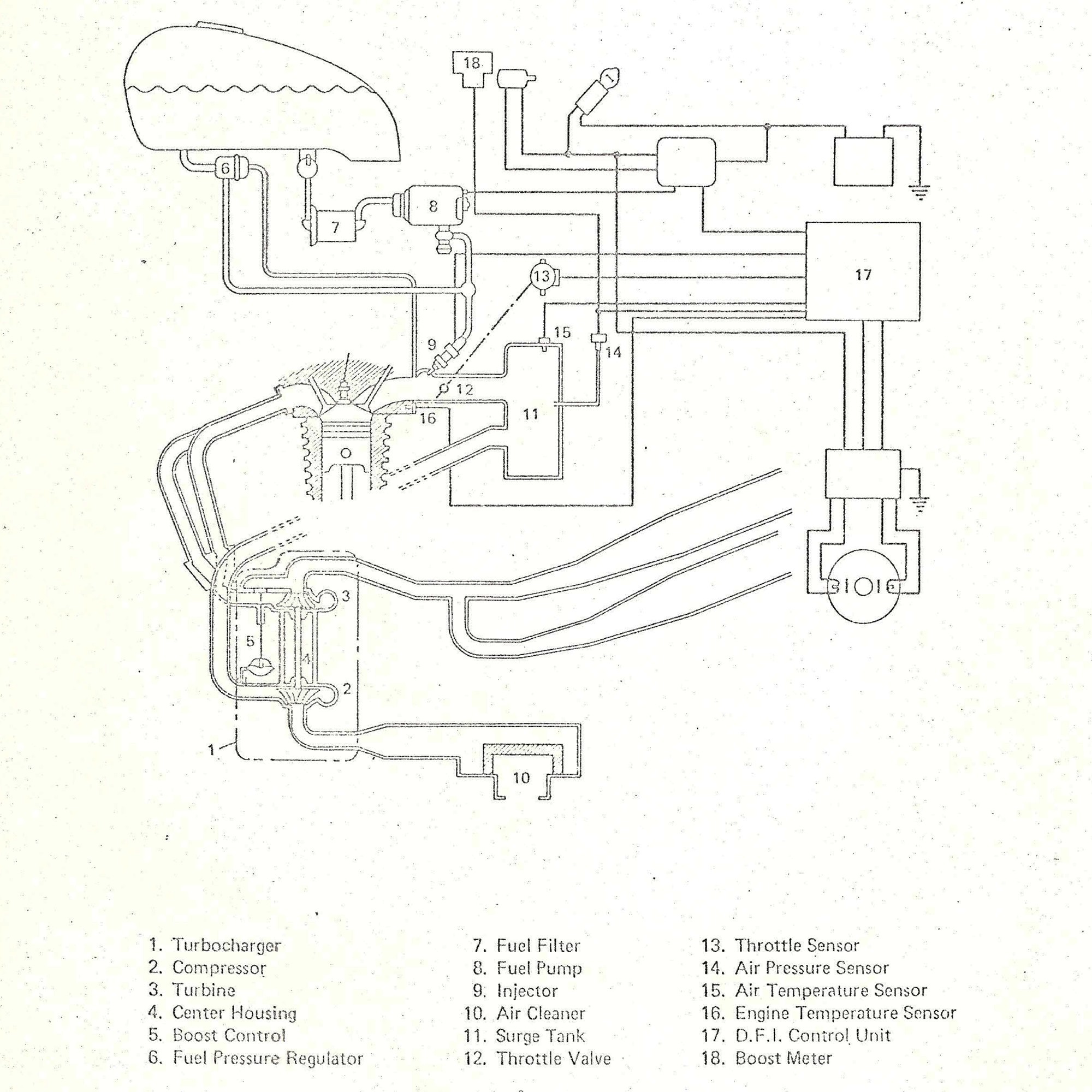

The Hitachi HT10-B turbocharger is mounted at the front of the engine crankcases, allowing the turbine to be fed by short head pipes and minimizing heat energy lost in the run from the exhaust port. After spinning the turbine, exhaust gases follow a pipe leading around the right side of the cases to the right muffler. Another pipe intersects the first underneath the engine and leads to the left muffler. There’s a small, oiled-foam element air cleaner located under the countershaft cover. Air reaches the turbo compressor through a plenum chamber running under the engine alternator cover, alongside the left frame rail. Compressed air from the turbo is forced through a black-chrome pipe which snakes around the left of and behind the cylinder block to the airbox. Mikuni fuel-injection throttle bodies with 30mm venturis connect the airbox to each intake port.

The turbo has a 47mm turbine wheel and a 50mm compressor wheel and is capable of turning 200,000 rpm. The fastest the turbo ever actually spins is 175,000 rpm. The shaft rides in two one-piece, floating plain bearings positioned between the turbine and compressor wheels. Pressurized oil feeds both the inside and the outside of each bearing shell, and the bearings themselves rotate at about 30 percent of shaft speed, avoiding cooling and lubrication problems. Maximum boost is 11.2 psi; when intake tract pressure approaches or reaches that maximum, a valve (popularly known as a wastegate) in the turbocharger housing releases exhaust pressure into the exhaust pipe, bypassing the turbine.

A digital microprocessor located in the tail section controls the Turbo’s fuel injection system: the amount of fuel sprayed into the intake ports depends upon throttle position, engine rpm, altitude, engine temperature, intake pressure and intake air temperature. The injection nozzles and the fuel pump are larger than the nozzles and pump on the GPzllOO. Closing the throttle at low rpm stops fuel delivery to the intake ports, which increases engine braking and fuel economy. Over-rev the engine and the system again cuts off the fuel supply. There’s an over-ride function built into the system so the bike can limp home if a sensor fails, and LEDs on the control box indicate what’s wrong for each component.

The frame of the 750 Turbo was similar in design to the donor GPz750, but was reinforced in key areas to handle the extra power. The suspension was also stiffened and lowered to keep wheelies at bay while under hard acceleration. Braking came courtesy of the calipers, cylinders, and discs of the GPzl100, which meant a pair of 280mm plates up front and a 270mm disc bringing up the rear.

Cycle World noted that the basic engine design was unchanged in the boosting process. It was still an air-cooled inline-four with two valves per cylinder and dual overhead cams. The turbo shares many parts with the GPz750 it came from, including the connecting rods, the crankshaft, and the cylinder block. The head was from the KZ650 and had 24cc combustion chambers, 2cc smaller than the chambers in the GPz750’s head. The main differences between the 750 Turbo’s engine and the GPz750’s were in the internals, as the 750 Turbo got cast three-ring pistons with thicker walls and a laminated steel head gasket.

Cycle World continues with the changes:

Valve sizes and angle are the same as the GPz’s, but valve duration and lift are reduced: intake duration is 32° shorter and exhaust duration is 26° shorter; intake and exhaust lift is 7.5mm, down from 8.5mm. Primary gearing is taller, and first, second, fourth and fifth gearsets have slightly altered ratios because the gears themselves have fewer, larger (and stronger) teeth. The changes raise overall ratios and reduce engine speed at 60 mph from 4400 rpm to 3900 rpm: the Turbo’s extra power allows it to use the taller gearing. The primary shaft damper in the GPz is rubber; in the Turbo it’s a more durable spring-loaded ramp – and – cam assembly. The clutch basket is reinforced and there are eight friction plates instead of seven. Every bearing in the transmission is bigger, and the transmission output shaft is larger diameter, up to 28mm from the GPz750’s 25mm. To discourage detonation, there’s less ignition advance, a maximum of 30° at 3300 rpm compared with the GPz’s 40° at 3600 rpm, and Kawasaki recommends gasoline with a minimum of 90 pump octane.

The line feeding oil to the turbocharger has a filter and the oil pump has 17 percent more capacity than the GPz750’s oil pump. A second oil pump scavenges the turbocharger, keeping oil from building up between the turbine and compressor wheels, seeping past the seals, and burning out the exhaust in a puff of blue smoke—a common problem, especially in the case of bikes fitted with aftermarket turbo kits. To keep the oil cool, there’s a four-row aluminum oil cooler mounted on the downtubes, below the steering head.

The 750 Turbo was also a bit of a technology demonstration. In addition to the fuel injection and computerization, the dash had an LCD segmented boost gauge, and the fairings had a neat aluminum brace. This brace strengthened the front fairing, but also tied the frame tubes together while also offering some protection for the turbo, which was more or less right behind the front wheel.

All of this made the 750 Turbo a pretty porky machine that tipped the scales at 552 pounds with a half tank of fuel, compared to a GPz750’s 516 pounds with the same setup. But the extra weight was worth it, because power blasted up to 112 horsepower and 73.1 lb-ft of torque.

The 750 Turbo Was Stupid Fast

How this translated into real-world performance was fascinating. Cycle Magazine got one tester through the quarter mile in 11.13 seconds at 120.32 mph. Cycle World did the same dash at a different strip in 11.40 seconds at 118.42 mph. Another Cycle World staffer allegedly did the deed in as quickly as 11.1 seconds. Meanwhile, Motorcyclist magazine claimed to have hit 150 mph on its 750 Turbo, which was 4 mph faster than the top speed quoted by Kawasaki. Drag racing legend Jay “PeeWee” Gleason recorded a 10.71-second quarter mile.

The motorcycle buff mags usually landed on the conclusion that the Kawasaki ZX750-E1 was either the fastest motorcycle they tested or was in the running to be the fastest. Kawasaki embraced this and marketed the 750 Turbo as the “World’s Fastest Production Motorcycle.” That might have been stretching the truth, depending on who you asked, but at the very least, it was the fastest of the turbo bikes and faster than most other vehicles.

Here’s what Cycle News said of the ride:

Webster’s is wrong. On page 508 of their New World Dictionary are listed some 20 different explanations for the word “‘fast,”’ and nowhere to be found is the definition “21. Kawasaki ZX750 Turbo.” Obviously the bespectacled wordsmiths in charge of such things at Webster’s haven’t had a chance to throw a leg over Kawasaki’s newest guided missile. That’s probably a good thing, though, because once they got a taste of the bike’s turbo-boosted, arm-stretching acceleration, they’d have to add definitions to all kinds of listings — words like “awesome,” “mind-boggling” and “‘fantastic.”

Theories are fine, but real-world performance is what makes or breaks a motorcycle. The Kawasaki Turbo definitely makes it. Kawasaki claims a top speed of 146 miles an hour and a quarter-mile time of 10.7 seconds for the Turbo and even our pre-production test bike with more than 5000 hard miles registered on the odometer felt like it could come fairly close to those figures. Those figures, by the way, not only make the Kawasaki the fastest production turbo bike, but make it just about the fastest thing —two- or four-wheeled — on the road. Even more impressive, though, is how fast the Kawasaki Turbo feels. Some new bikes — we’re thinking especially of the Honda Interceptor — are fast in a deceptive kind of way. They get up to speed so smoothly and easily that they’re almost civilized. None of that behavior for the Kawasaki; it’s about as subtle as a slap alongside the jowls with a sockful of loose nickels. When the Turbo starts making power, you know about it. All the while accompanied by a jetfighter-like howl from the turbocharger, the Kawasaki simply launches away from a stop. Although a little tricky to get underway quickly because of a high first gear, the Turbo’s front wheel is soon enough pawing for air. A shift to second lofts the front end again, and after that it’s just a matter of upshifting and watching the speedometer and tach winding rapidly towards their limits. A guaranteed pulse-quickening, adrenalin-pumping rush everytime.

A trip on the freeway with the Turbo is an exercise in frustration. At a socially acceptable cruising speed, the bike is just under its boost range. Pick the speed up a little and the first of the LCD wedges on the above-tach boost gauge light up, begging to be joined by more of its kind. A quick check in the mirrors and it’s fullboost city, followed very soon by a roll-off of the throttle when you realize what a 100-mile-an-hour ticket would do to your wallet. A few miles down the road, though, caution gives way to enthusiasm and the whole delightful process repeats itself. Rolling on the throttle in fifth gear from cruising speeds, some turbo lag is evident as the bike takes a moment to gather itself before rocketing ahead; It’s never much of a problem, but for those thrill seekers who want a more immediate punch of power, a downshift to fourth helps considerably.

The Ride Wasn’t Perfect

While most reviews seem to agree that the 750 Turbo had the least turbo lag of all of the turbo bikes, the difference between how the bike rode under boost and out of boost was pronounced. Cycle World called the 750 Turbo a “wimp on wheels” when it wasn’t in boost, and likened the non-boost performance to being like riding a 400 that weighed as much as an 1100.

Sadly, it seemed as if Kawasaki sort of failed to make a turbo motorcycle that didn’t have split performance. However, apparently, the 750 Turbo was so fast and so fun to ride that reviewers were willing to forgive how the bike rode out of boost.

Kawasaki priced the 1983 750 Turbo at $4,599. That made the turbo bike slightly more expensive than the Kawasaki GPz1100 from the same year, which was $4,499. However, depending on who you asked, that extra $100 got you a faster bike. Reviewers also remarked about how the 750 Turbo started with ease every single time and didn’t even demand choke when running on a cold morning. Kawasaki didn’t just make a turbo bike, but also made turbocharging reliable.

Quirks were few. The turbocharging meant that you had to change the motorcycle’s oil every 1,500 miles, and it was advised that you let the engine idle for a minute or so after a ride to ensure the engine is properly lubricated and that the turbo had some time to cool down.

The Best Turbo Bike Still Failed

Unfortunately, building the best turbo motorcycle on the block wasn’t enough. The Kawasaki went like stink, but was still a highly complex machine that demanded your attention. Most riders would decide to sacrifice a little speed to get a simpler Kawasaki GPz1100, a Kawasaki GPZ900R, or a Suzuki GSX1100 Katana.

Ultimately, Kawasaki pulled the plug on its turbo program in 1985. The turbo motorcycles of the 1980s all failed for similar reasons. Most of these motorcycles were just too heavy, too complex, too expensive, too laggy, and not fast enough to justify their continued existence. The Kawasaki 750 Turbo did solve some of those, namely the lag, the price, and the performance, but at the end of the day, buyers still chose simpler designs, anyway.

The march of time and technology also made these motorcycles sort of obsolete. Today, it’s possible to make big power out of small naturally aspirated engines, and big bikes can get decent fuel economy, too. Forced induction projects are few outside of the custom bike and racing bike world. Yamaha built a turbocharged three-cylinder prototype motorcycle in 2020. Honda is working on a V3 engine with an electric compressor. The most famous boosted bike is the frankly ridiculous Kawasaki Ninja H2. Otherwise, if you’re a motorcycle company, you just make something that’s naturally aspirated or is electric.

It’s estimated that America got 3,500 Kawasaki 750 Turbos between 1983 and 1985. That’s a small number, and what’s sadder is that, in 1995, it was estimated that only 15 percent of them were still on the road. It’s unknown how many made it another three decades to today. The good news is that there are survivors out there. A 1984 model sold for $18,725 at Iconic Motorbike Auctions, while a 1985 model went for $6,901 on Bring a Trailer. One outlier appears to be a 1985 example that was sold at Mecum for $27,500 in 2025. There’s one 750 Turbo currently for sale at Iconic Motorbike Auctions for $10,058.

The Kawasaki 750 Turbo was the end of a very short era. Japan’s turbo motorcycle craze came and went in under a decade, then never really came back. These turbo bikes were very much products of their time, a period when Japan flexed its engineering muscles and sometimes built insane vehicles just because they could. All of these motorcycles might have been failures, but it’s still so cool that they existed in the first place. For a brief moment in time, the future of motorcycling was thought to be in forced induction. That didn’t happen, but I doubt people cared when they raced off into the sunset with their metal snail singing.

Top graphic images: Iconic Motorbike Auctions; Kawasaki

The H2R makes 322 HP. That just boggles my mind. I’d wish I could take one to an airport runway and see what that’s like. I ride a VFR800 with 108 HP and that’s good for a 3 second 0-60. Plenty!

I got to ride a 500km-new S1000RR on track and that makes a claimed 207hp. I can’t fathom a nearly 50% increase over that. I bet the initial launch would be similar, since both would just loop if they gave close to full power. I bet the H2R really starts to shine in 4th gear or so, just endless acceleration.