The muscle car era of the 1960s and early 1970s was a defining moment in automotive history. America’s automakers cranked horsepower to hilarious levels, and then dropped those engines into cars that you didn’t need Ferrari money to buy. But not everyone was able to afford something like a Pontiac GTO or an Oldsmobile 442, especially someone just getting started in a career. Oldsmobile was one of the automakers that tried to cater to this demographic with the Oldsmobile Rallye 350. This one-year special edition gave buyers 442-like muscle car looks and some of the speed for a more accessible price.

Automakers have worked tirelessly for decades to attract young car buyers. A younger buyer might not be able to afford a flagship, but they’re still an important demographic. Someone who buys your cheaper car when they’re young may become hooked and upgrade to more expensive models as they age. At the very least, if you can sell cars to the “yutes,” that’s a whole new income stream!

Most, if not all of your favorite brands have had to consider young buyers at some point in their histories. Chasing younger buyers is why BMW built the 3 Series Compact and is part of the reason for the Porsche Boxster’s existence. At the same time, a car that targets a younger buyer is often also good for an older buyer who doesn’t have a ton of cash on hand. The fact is that some folks may never be able to afford a BMW M5 or a Porsche 911.

This was the case during the old muscle car era. Automakers knew that not everyone could pony up the cash for the flagship muscle cars that kids had on their walls. A lot of folks couldn’t afford the high insurance rates for a flagship muscle car, either. The solution was simple. What if you offered musclecar style and some performance, but with much lower insurance rates and a more affordable price of entry?

Last year, I wrote about how Pontiac did just that with its GT-37. If you couldn’t afford the fabled GTO or its insurance, you could get a car that looked the part and still went fast, but was easier on your wallet. Chevrolet followed down a somewhat similar path with its Heavy Chevy, a car that looked as hot as a Chevelle SS for a lot less coin. These cars, along with competition like the 1970 Dodge Dart 340, are known more as “junior” muscle cars.

Today, we’re going to look at yet another time when Detroit tried to lure in muscle car lovers who had lighter wallets. The 1970 Oldsmobile Rallye 350 was a muscle car that was meant to look great and be cheap to insure right from the start.

Setting The Stage

1970 was the absolute peak of the old muscle car era. This year produced some of the most iconic American cars in history. The hottest Chevrolet Chevelle had a gross 450 horsepower LS6 V8. Nipping on its heels was the 425 HP V8 Plymouth Hemi ‘Cuda, Pontiac GTO and its 370 HP Ram Air IV V8, and Oldsmobile’s own 442 W30, which punched out 370 HP through, you guessed it, a V8. These engines were colossal units, too, with the Chevelle’s coming in at 454 cubic inches, or 7.4 liters in more modern terms. The Oldsmobile 442 W30 had a slightly bigger engine with 455 cubes on tap

The beauty of these muscle cars was that they had these titanic engines, mid-size bodies, luxurious interiors, and surprisingly reasonable price tags. In 1970, a Chevrolet Chevelle had a base price of $2,719 ($23,363 in 2025). For $4,276 ($36,741 in 2025), you got the best of the Chevelles with the LS6 V8.

What was far less reasonable were the insurance rates. By 1970, the insurance industry was clued in to what was happening in Detroit. If you were brave enough to buy a racecar for the street, your insurer was happy to saddle you with high costs to keep it legal.

High insurance rates were such a big deal that they made national news. In 1970, the New York Times reported that State Farm Mutual had conducted a three-year study and found that muscle cars had 56 percent higher insurance losses than regular cars. Collision claims were 50 percent higher than regular cars, while comprehensive claims were a shocking 117 percent higher. In other words, the people who bought muscle cars often found ways to wreck them, which isn’t too different than today, really.

Allegedly, insurance rates for muscle cars skyrocketed to $1,000 ($8,592 in 2025) to $1,500 ($12,888 in 2025) a year for a muscle car. Considering that these cars cost over $4,000 on the high end, that was shocking. Imagine having to spend nearly the value of a Mitsubishi Mirage every year in just car insurance. The Oil Crisis and the emissions era often get blamed for the death of muscle cars, but absurd insurance rates were absolutely a contributing factor.

Automakers didn’t take this lying down and created some of the budget muscle cars that I mentioned earlier. While these cars looked the part and even had powerful engines on their own, they often managed to fly under the insurance radar. For Oldsmobile, this meant making a cheap muscle car. This would end up being the single year only Rallye 350.

Beating Insurance Companies

The February 1970 issue of Motor Trend explained why the Oldsmobile Rallye 350 came to be. Motor Trend reported that, at the time, many insurance agents were looking to see if a car weighed less than 10 pounds per horsepower. If your car met that criteria, you got hit with insurance expensive enough to purchase a used car.

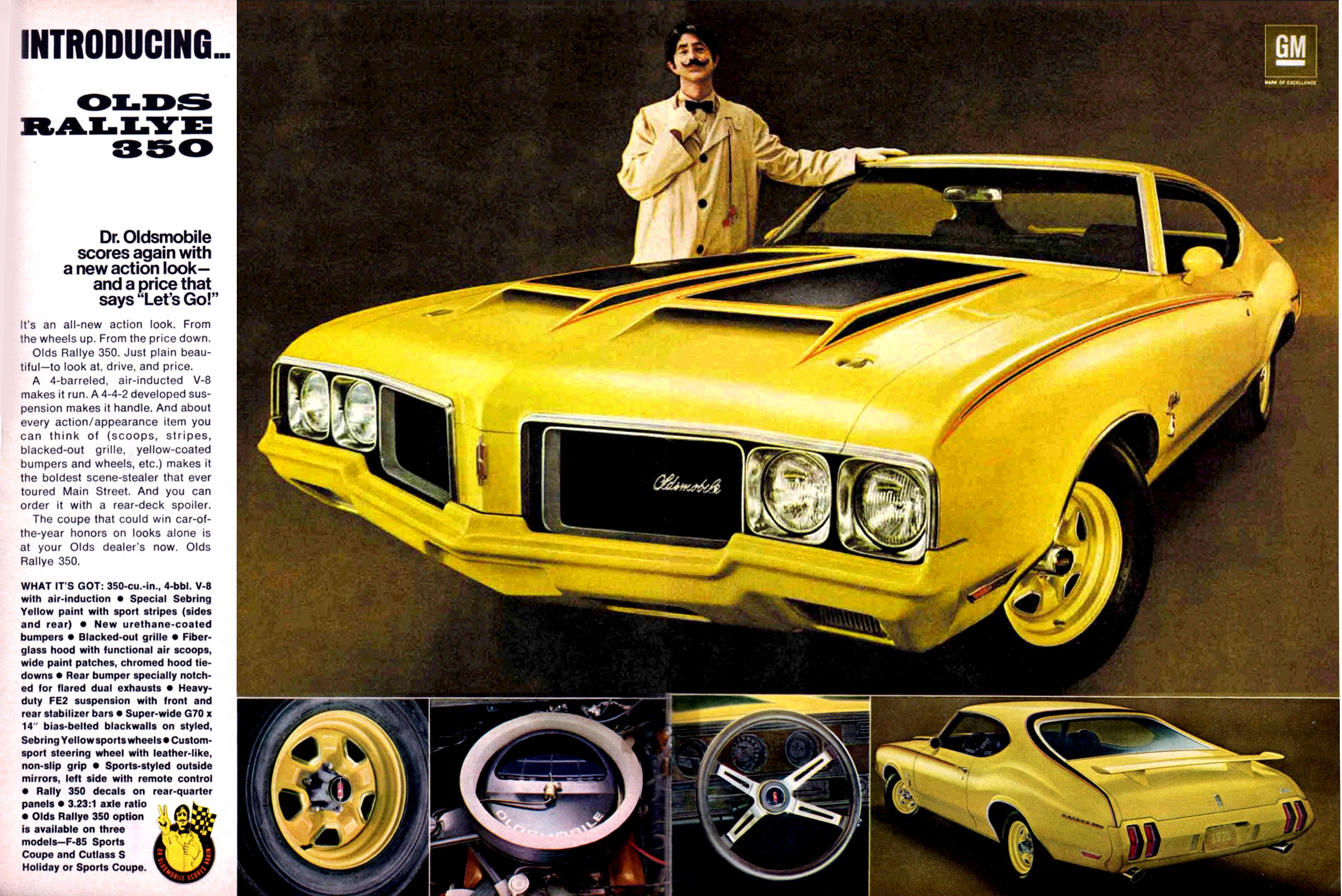

This was troublesome for many buyers, but especially the younger buyers that Oldsmobile wanted to keep around. But this was more than just trying to cast a wide net to buyers. By 1970, brands like BMW had become popular with young buyers, and GM’s brands took the ascension of Germany’s brands as a threat to their bottom line. Motor Trend‘s article on the Rallye 350 actually pitched the baby muscle car as something a young person could consider instead of a BMW 2002.

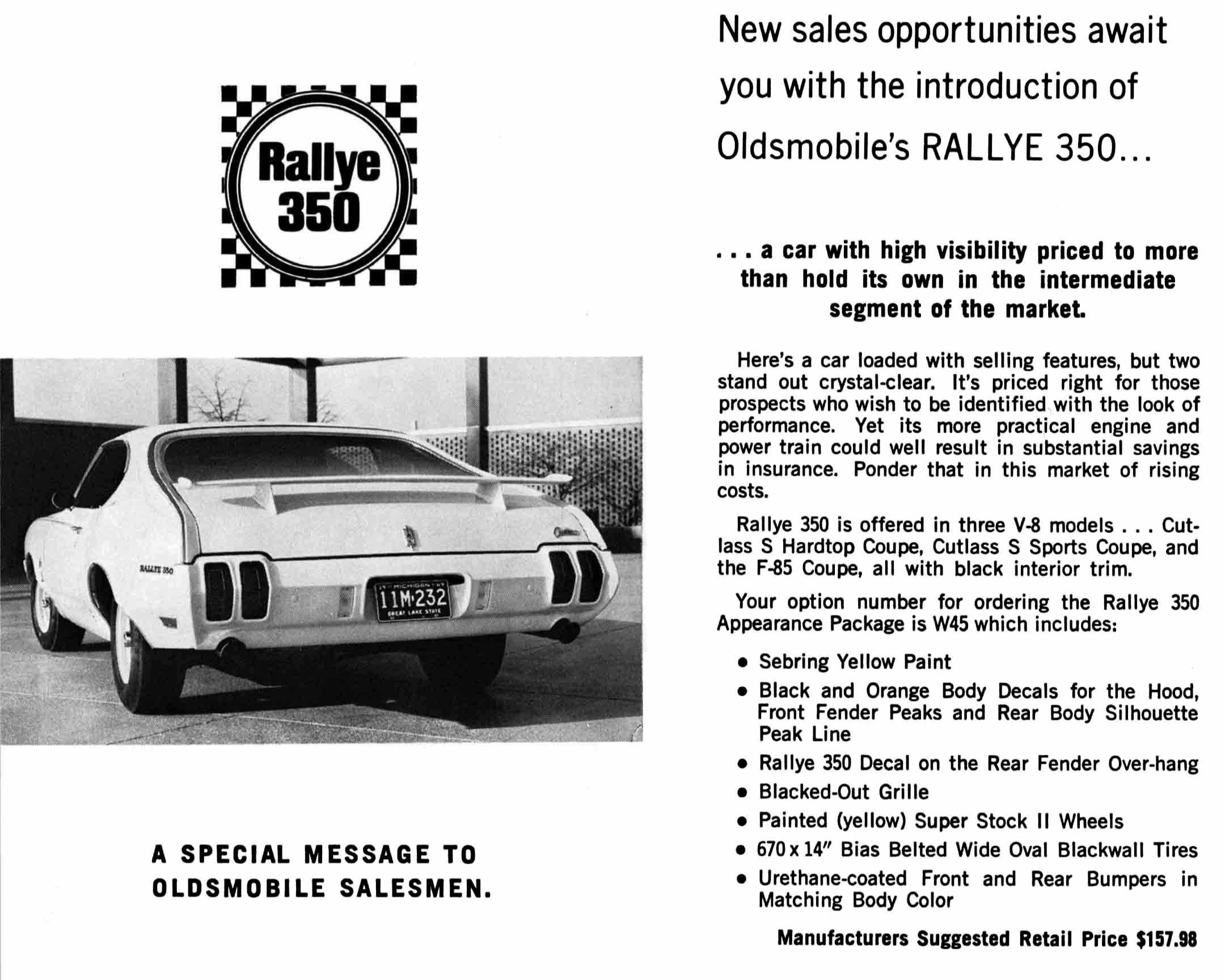

Oldsmobile General Manager John Beltz launched the Rallye 350 on February 18, 1970 at the Chicago Auto Show. By that point, the car had already been in production for about a month, and Oldsmobile was advising dealers and salesmen on how to reel in buyers. From the Oldsmobile “A Special Message To Oldsmobile Salesmen” pamphlet:

Here’s a car loaded with selling features, but two stand out crystal-clear. It’s priced right for those prospects who wish to be identified with the look of performance. Yet its more practical engine and power train could well result in substantial savings in insurance. Ponder that in this market of rising costs.

Oldsmobile was also quite open in that the Rallye 350 was more about looks than actual performance:

The Rallye 350 fits competitively into an existing product group made up of performance appearance packages added to intermediate price leader models. Competitive makes are the Plymouth Road Runner, Ford Torino with the GT option and Dodge Super Bee. Pontiac’s GTO Judge is similar in appearance. But the “Judges” are top-of-the-line intermediates with a much higher price tag and a standard ultra-high performance engine and power train.

Our Rallye 350 is offered with the L74 (Cutlass Supreme) engine. It provides unquestioned performance at a level that may offer substantial insurance rate benefits to the buyer. Remember this … the Rallye 350 will find its greatest appeal to the prospect who wishes to identify with the “performance look”… the NOW look … that has been happily combined with the practical aspects of a more conventional engine and power train.

Immediately after, Oldsmobile said the Rallye 350 was made for the kind of person who knew that the high-end muscle cars were out there, but specifically wanted something that looked unusual, was cheap, and practical.

The Rallye 350 package was applied to the Oldsmobile Cutlass Holiday Coupe, F-85 Club Coupe, and the F-85 Sport Coupe. All of these variations were A-body cars, which served as the underlying platform for GM’s go-fast intermediates of the era.

The Cutlass was introduced in 1961 as an upmarket version of the F-85 senior compact. These cars were initially on the GM Y-body platform before moving to the larger A-body platform in 1964. GM’s A-body platform went through several iterations over the decades. The platform made its first appearance in 1926 and underpinned several cars and trucks over the decades. Then, in 1982, the A-platform switched to front-wheel-drive.

In 1964, the A-platform launched, and at the time, it had some fresh ideas. A-body cars featured full perimeter frames and four-link coil rear suspension. Most cars riding on the A-body platform had 115-inch wheelbases, except for wagons, which got an extra five inches. As Hagerty writes, GM demanded that its intermediates didn’t have engines with more than 330 cubes of displacement. Pontiac loved breaking this rule, first by calling its 336 cubic inch V8 engine the Pontiac 326, and then by creating the GTO by calling its 389 V8 a low-volume option. By 1965, GM raised the ceiling to 400 cubic inches.

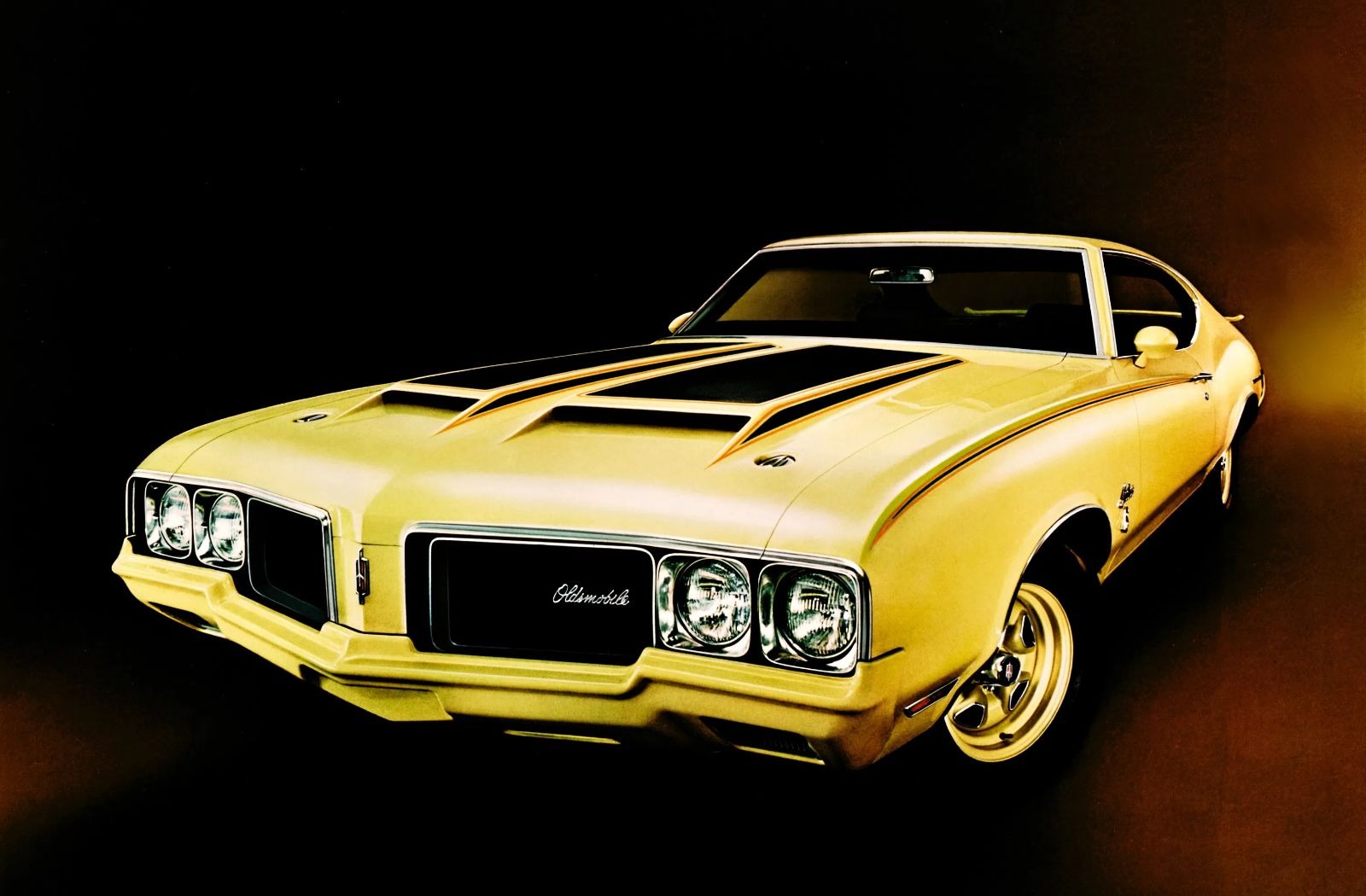

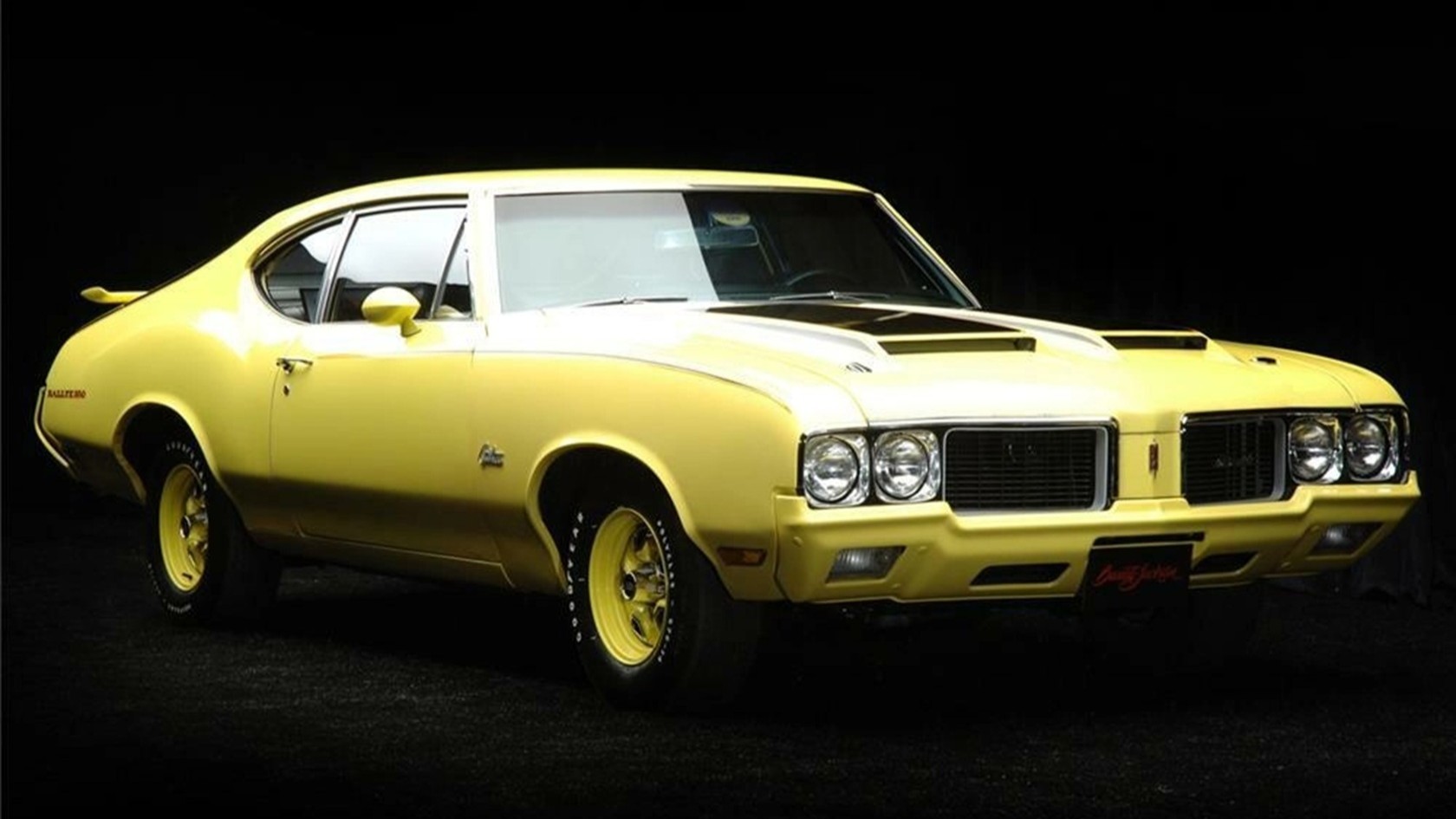

Eye-Searing For A Reason

The brilliance of the Rallye 350, like the rest of the so-called junior muscle cars, is that they were largely created by raiding existing parts bins. Here’s what Oldsmobile said it did to create the Rallye 350:

Sebring Yellow Paint.

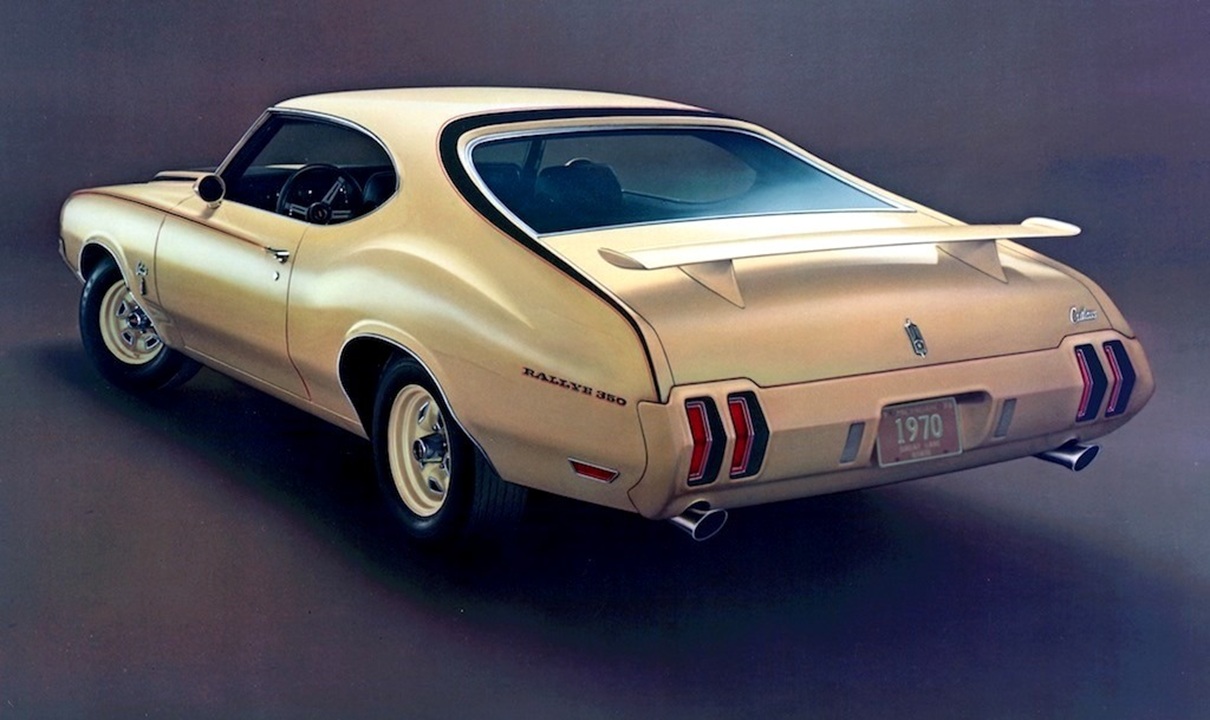

Black and Orange Body Decals for the Hood, Front Fender Peaks and Rear Body Silhouette Peak Line.

Rallye 350 Decal on the Rear Fender Over-hang.

Blacked-Out Grille.

Painted (yellow) Super Stock II Wheels.

670 x 14″ Bias Belted Wide Oval Blackwall Tires.

Urethane-coated Front and Rear Bumpers in.

Matching Body Color.

Oldsmobile said that you got all of this for the sum of $157.96. However, the package didn’t stop there, as cars with the Rallye 350 package had a list of required options, from Oldsmobile:

W25 Force-Air Fiberglass Hood.

L74 350 cu. in. 350 h.p. high compression engine with standard 3/23:1 axle ratio.

N10 Dual Exhaust System.

FE2 Rallye-Sport Suspension with front and rear stabilizer bars.

D35 Sports-styled Outside Mirrors.

N34 Custom-Sport Steering Wheel.

Add it up, Oldsmobile said, and a buyer would have to pay $3,252.84 to get their low buck muscle car. Oldsmobile was happy to point out that the Rallye 350 was $67.16 cheaper than a comparable Plymouth Road Runner.

Oldsmobile was also quite proud of the urethane bumpers, too, and devoted a whole section of the brochure to explain why:

A real red-hot selling feature is the urethane coated bumper material of the Rallye 350. This is a magic-like substance that can be likened to an “elastic plastic”. It is applied to the metal bumper forming a protective coat of urethane in yellow primer color. Baked out at 250 degrees Fahrenheit the bumper is then sprayed with Sebring Yellow paint. A urethane (pronounced you-ra-thane) coated surface has a number of advantages over both painted and chrome plated bumper surfaces. Exhaustive tests have proved its superior resistance to minor abrasions, corrosion, blisters, chipping, and has also shown a marked indifference to an assortment of scratches and scars. As for minor dents, the urethane treated bumper can be “banged out” without having to refinish the surface.

When subjected to more severe dents, the surface can be restored to its off-the-line condition by sanding and repainting it with a urethane lacquer. Other tests have proved without question that urethane coated bumpers are superior to paint and chrome plated bumpers when exposed to extreme salt spray, humidity and thermal shock (minus 20 degrees to live steam.) Bumper jack tests also put the urethane bumper in a favorable light.

All of this was wrapped in a package that was painted in bright Sebring Yellow paint. This paint wasn’t just limited to the body and bumpers, either, but it also made it over to the wheels. Oldsmobile said the looks were one of the key parts to getting buyers into showrooms, but insurance was also a key part. The smaller, less powerful V8 meant that a buyer could get muscle car looks without having to pay muscle car insurance.

Oldsmobile also wanted to use the car as bait. A dealer was to put a Rallye 350 in the middle of the showroom and surround it with Cutlass, Cutlass S, Cutlass Supreme, Supreme SX, 442, and Delta 88s with the idea that if the person didn’t buy a Rallye 350, maybe they’d buy one of those other cars. Oldsmobile ended its dealership pamphlet by saying that the Rallye 350 was going to be the next big thing for Oldsmobile.

When the Rallye 350 launched, it actually shipped with 310 horsepower under the hood rather than the 350 advertised to dealers. But that was fine, because it further helped buyers keep in the good graces of their insurance companies. The engine also wasn’t entirely stock, as it did get the aforementioned upgraded intake and exhaust. Not noted above is that the Rallye 350 also got a 4MV Rochester Q-jet four-barrel carburetor like the ones found in 442s with manual transmissions.

In terms of gear changes, buyers had the option of a Turbo Hydra-Matic 350, a three-speed column-shift manual in an F-85, or a floor-mounted three-speed manual transmission in a Cutlass variant. Reportedly, a Muncie four-speed is also noted on the Rallye 350’s order form, but it’s not known if any cars were built with it.

Pretty Quick

Motor Trend tested the Rallye 350, and the test car completed a quarter mile in 15.4 seconds at 89 mph. 60 mph was dispatched in 7.7 seconds. Hemmings notes that, in different hands, the Rallye 350 could hit the quarter in 15.27 seconds at 94 mph and hit 60 mph in 7 seconds. Either way, Motor Trend called the straight-line performance adequate.

Where the car really stepped up, Motor Trend said, was in handling. Sure, drum brakes were standard and power steering was optional, but Motor Trend pointed out that since the Rallye 350 had many of the bones of the 442, it was great when the going got twisty. Much of the credit for the Rallye 350’s suspension tuning went to engineer and SCCA racer Marv Thompson.

Motor Trend even went as far as to say that the Rallye 350 was one of 1970’s most tossable cars, in part for the fact that you could just enter a corner and use the throttle to determine how much drama you want to cause. The review further stated that the Rallye 350 had a neutral feel in slow corners and understeer in fast ones. The only part of the handling experience that Motor Trend didn’t like was the steering, which the magazine said was quick enough, but totally numb.

Ultimately, Motor Trend said, the Rallye 350 wasn’t really going to win races, but you were probably going to have enough fun and save money doing it. The publication’s recommendation was to go with one based on the Cutlass and not the F-85 since the latter’s bench seat isn’t exactly sporty.

Oldsmobile never intended the Rallye 350 to be a volume seller. It was expected to sell at least 2,000 examples, and maybe as many as 4,000 units. Oldsmobile built 3,547 Rallye 350s, most of which were built out of Cutlass Holiday Coupes.

Too Yellow For Its Own Good

The Rallye 350 turned out to be a bit of a weird flop. Yes, Oldsmobile built more Rallye 350s than the minimum it wanted to make, but as Hemmings writes, most of these cars were not customer orders. Instead, dealers and Oldsmobile zone representatives ordered up most of the cars. That makes sense since Oldsmobile also pitched the car to dealers as a way to move other stock.

Dealers had a hard time selling the Rallye 350. Hemmings notes that some dealers found it hard to sell the Rallye 350 because it had way too much yellow going on. Dealers got desperate enough to contrast the yellow by adding trim rings to the wheels and, sometimes, by throwing away the yellow bumpers and replacing them with chrome bumpers. Apparently, the Rallye 350 sold so slowly that there were still plenty of unsold examples out there in 1971.

The public reception was so lackluster that Oldsmobile didn’t even attempt to make a 1971 model. As sad as that sounds, it wasn’t particularly surprising. Pontiac experienced a similar issue with trying to get people to buy its GT-37. The discount muscle car was a good idea on paper, but most buyers still wanted the flagship, anyway, regardless of how expensive it was to insure.

The good thing about this is that, like the other under-the-radar muscle cars I’ve written about, the Oldsmobile Rallye 350 has remained attainable. The average selling price for a good example has trended at about $32,000, with less-than-perfect examples going for less than that. A nice 442 could easily go for twice that price. Of course, the 442 is also a much more famous car with more juice under the hood to match.

I have always found this part of car history to be fascinating. Automakers have invested so much into trying to attract younger buyers. Detroit also gets clever to avoid roadblocks. All of these junior muscle cars were designed to look like muscle cars, but not require muscle car money. It’s something that still happens today, too, but with a lot more success.

So, if you’re looking for a classic muscle car but aren’t made of money, try finding a version of your favorite car that’s a step down or two from the flagship. Sure, it won’t be as fast, but you’ll find something more accessible and your bank account will thank you later.

Top graphic image: Mecum Auctions

I wonder if anything else got the urethane bumper treatment. Maybe not in banana yellow, but I could see it being great for utility vehicles that often had white painted bumpers back then.

WAY back in my high school days, my lady friend’s dad had one & she used it all. the. time. I thought it was a really cool car. And with that “breathed on” 350 under the hood, it would really scoot! Nice bench seat too 😉