Some of the world’s most complicated engines were created to achieve a specific objective. These engines were built to satisfy monster power requirements or to hit a high level of performance within tight size and weight constraints. Others are just wild engineering projects. The free piston engine was once seen as the “Engine of Tomorrow” because of its few moving parts, ability to run on almost anything that burns, lack of a crankshaft, and proposed low cost. Some of these engines actually went to work, and one of the weirdest applications came from Ford. What exactly did the blue oval guys do with an engine that had one cylinder, two pistons, and a turbine? They put it in a tractor.

The vast majority of internal combustion engines operate on a similar concept: They have pistons that combust a fuel-air mixture using gasoline ignited by a spark, or diesel ignited by compression. Many engines out there are also powerful turbines, and some are weird Wankel rotaries. Fewer engines are radials. But countless innovators throughout history have cranked up some truly strange designs.

I have been writing an informal series on the most complicated engine of all time. The headliner, I think, remains the three-block, 18-cylinder, and 36-piston Napier Deltic. It was designed to satisfy the power requirements of British fast boats in a time when regular diesels couldn’t cut it. The Brits also made the Commer TS3, the opposed-piston diesel truck engine that punched out healthy power in a compact package.

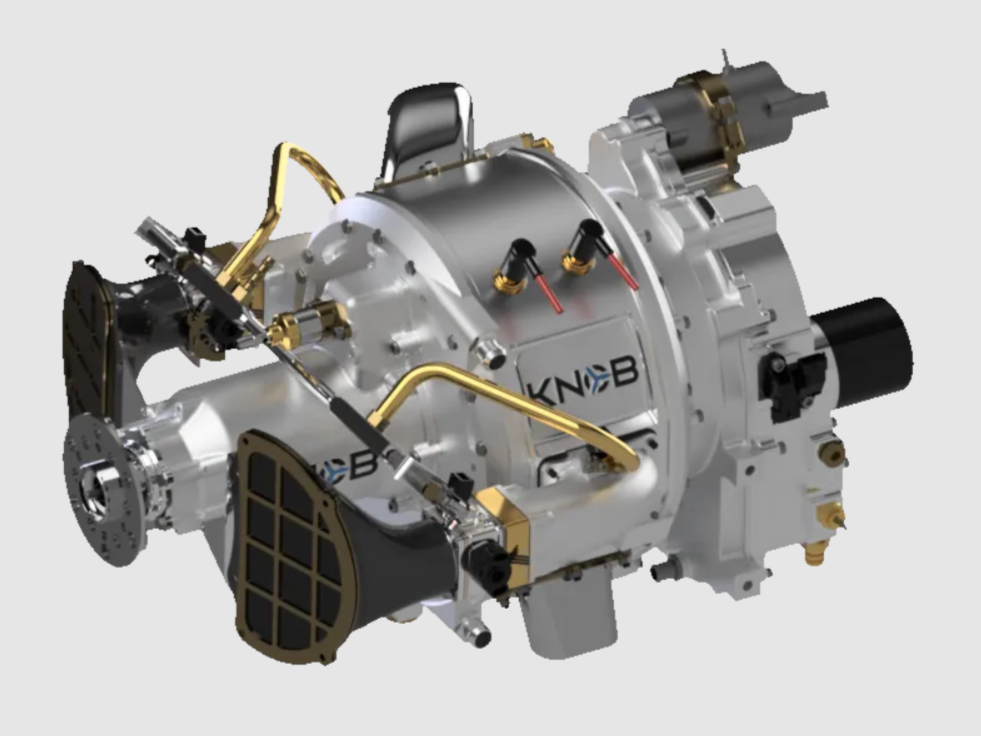

Most recently, I wrote about the Knob Engines Birotary, a new aviation engine that has a rotating block, three cylinders, and a stationary head. That crazy engine exists for light aircraft as a solution for a powerplant with low weight, low vibration, high balance, and lots of power.

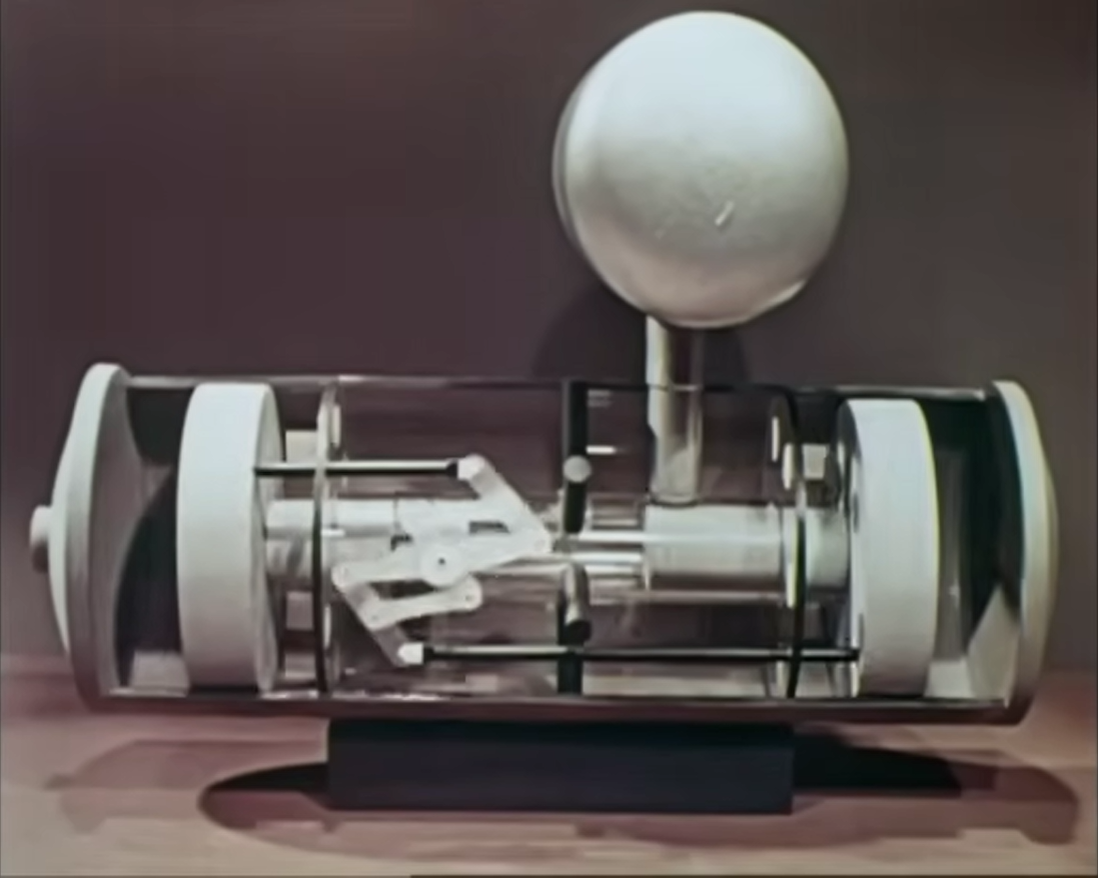

The Ford Motor Company of the 1950s brewed up what some journalists thought was the engine of the future. At a time when the gas turbine was all the rage, Ford experimented with a new kind of piston engine. The free-piston engine had no crankshaft, but one cylinder and two pistons. When running, this engine fires exhaust gases out to drive a turbine, which then drives the wheels of a vehicle.

This engine, which eliminated most moving parts from piston engines, promised better efficiency, lower manufacturing costs, and the ability to run on nearly anything that burned. So, what happened? Why aren’t we all driving cars and trucks that have pistons that aren’t connected to cranks?

The Free-Piston Engine

The most basic definition of a free-piston engine is that it’s a piston engine where the pistons aren’t married to the rotation of a crankshaft. The pistons in these engines move as a result of gas and load forces, not the rotation of engine internals.

The practical, modern free-piston engine is about a century old. In 1922, Argentinian engineer and attorney Raúl Pateras Pescara de Castelluccio began exploring free-piston engine technology. Others exploring the technology included aviation pioneer Junkers and M. Matricardi, who patented a free-piston design in 1912.

Prior to diverting his research to free-piston engines, Pescara was better known for his contributions to aviation. In the early 1910s, Pescara and Italian engineer Alessandro Guidoni designed a seaplane that would be built into a scale model and tested by the famous Gustave Eiffel. The seaplane design failed to become a successful aircraft, but that never stopped Pescara. He’d later move into helicopters, where Pescara was a pioneer in using cyclic pitch to control a helicopter and advanced the concept of using autorotation for helicopter emergency landings. In later years, Pescara would get into car manufacturing and air compressors.

Pescara’s free-piston design helped ignite a curiosity in several future engineers. Pescara developed a gasoline-fired free-piston engine in 1925 before trying out a compression ignition engine in 1928. Pescara patented his engine in 1928, continued his work on free-piston engines, and in 1941, created a multi-stage free-piston air compressor engine.

A review by R. Mikalsen and A.P. Roskilly at the Sir Joseph Swan Institute for Energy Research, Newcastle University, explains that there are several types of free-piston engines. The most basic design is the single-piston free-piston engine, which is described as:

This engine essentially consists of three parts: a combustion cylinder, a load device, and a rebound device to store the energy required to compress the next cylinder charge. In the engine shown in the figure the hydraulic cylinder serves as both load and rebound device, whereas in other designs these may be two individual devices, for example an electric generator and a gas filled bounce chamber.

A simple design with high controllability is the main strength of the single piston design compared to the other free-piston engine configurations. The rebound device may give the opportunity to accurately control the amount of energy put into the compression process and thereby regulating the compression ratio and stroke length.

Then there’s the dual piston design, from Newcastle University:

The dual piston (or dual combustion chamber) configuration, has been topic for much of the recent research in free-piston engine technology. A number of dual piston designs have been proposed and a few prototypes have emerged, both with hydraulic and electric power output. The dual piston engine configuration eliminates the need for a rebound device, as the (at any time) working piston provides the work to drive the compression process in the other cylinder. This allows a simple and more compact device with higher power to weight ratio.

Some problems with the dual piston design have, however, been reported. The control of piston motion, in particular stroke length and compression ratio, has proved difficult. This is due to the fact that the combustion process in one cylinder drives the compression in the other, and small variations in the combustion will have high influence on the next compression. This is a control challenge if the combustion process is to be controlled accurately in order to optimise emissions and/or efficiency. Experimental work with dual piston engines has reported high sensitivity to load nuances and high cycle-to-cycle variations.

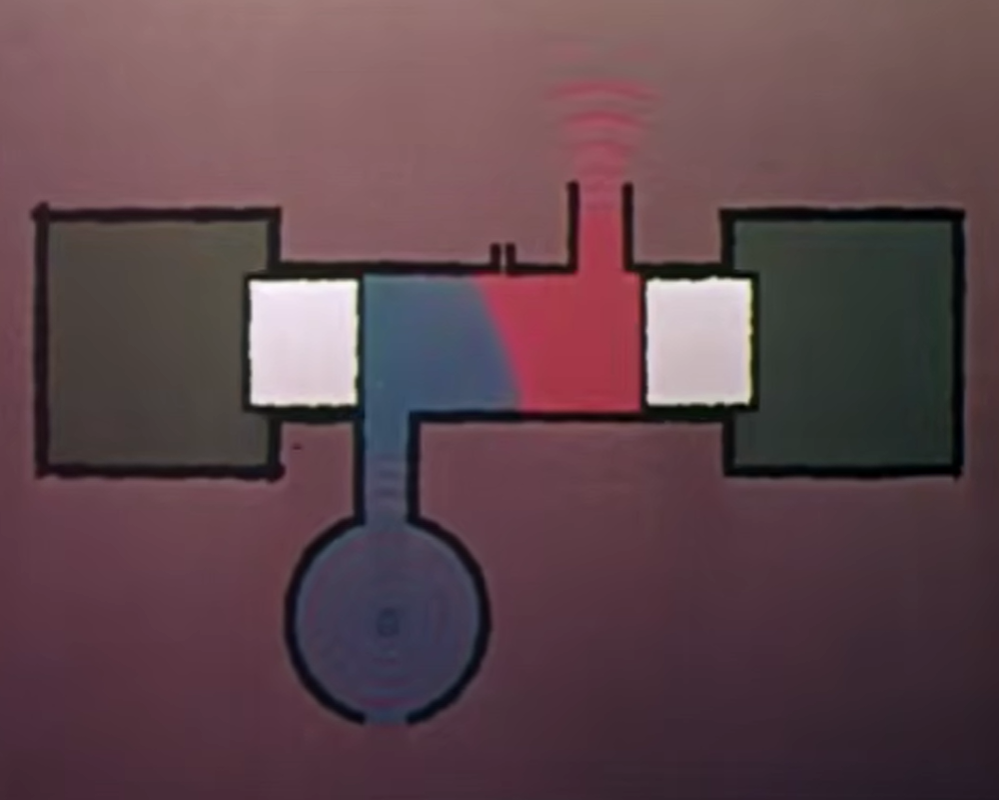

The free-piston engine gets weirder still with an opposed-piston variant. An opposed-piston free-piston engine is essentially two single-piston free-piston engines that have their pistons coupled together through a linkage. Like a more typical opposed-piston engine, an opposed-piston free-piston features a single cylinder and a single combustion chamber, plus two pistons. These pistons close in on each other, fire, and then blow outward.

The linkage keeps the pistons better synchronized, and the opposed-piston free-piston engine is known for its balance, lack of vibration, higher efficiency, and better scavenging. Many of the free-piston designs made from the 1930s to the 1960s utilized this design. However, as Newcastle University notes, those engines were bulky and complicated.

The “Engine of Tomorrow,” as Popular Science called it in 1957, was a step forward called the free-piston gas generator.

The Ford Typhoon

As Popular Science wrote, in 1954, Ford engineer Paul Klotsch wanted to build an engine that had been at the back of his mind for a while. In 1952, Renault built the Class 040-GA-1, the world’s first gas-turbine mechanical locomotive. This locomotive was powered by an opposed-piston free-piston engine that shot its exhaust into a turbine, which drove the 1,000 HP locomotive’s wheels through a transmission. Other free-piston gas generators were proving their worth in French naval use.

Check out what that locomotive looked like:

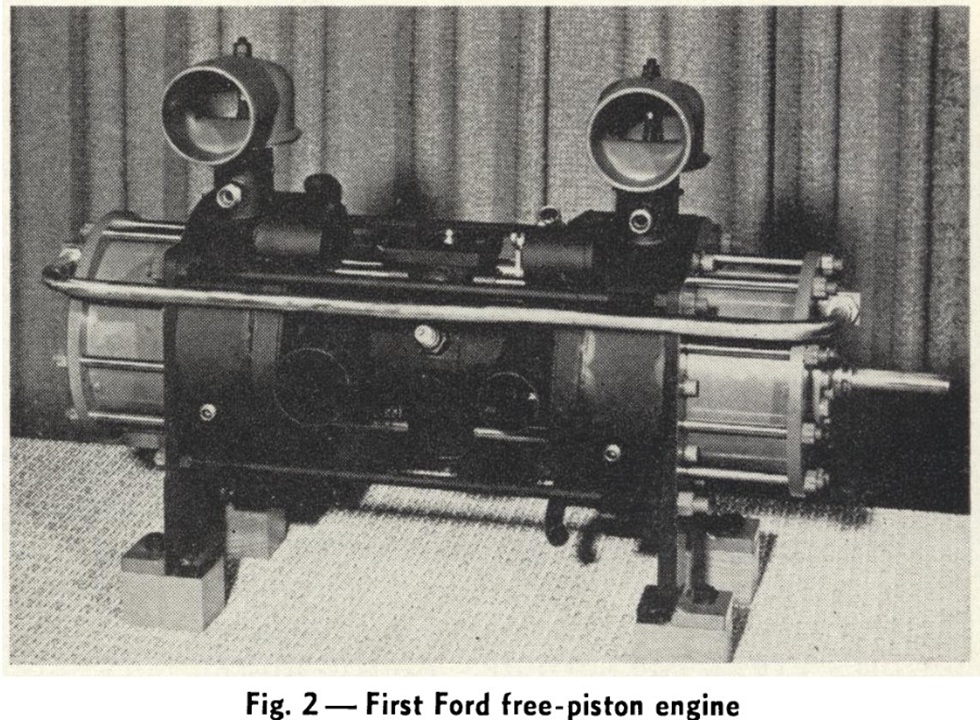

Klotsch believed that there was a future for free-piston gas generators, but on a much smaller scale. Engines that could possibly find their way into everyday vehicles. He pitched his free-piston engine design to Ford brass, who gave him the cold shoulder. Undeterred, Klotsch found an abandoned, unheated shed on Ford’s campus. The woodshed had only a single light bulb. Klotsch and his three helpers had to work completely bundled up and in near darkness. Yet, they did it. Klotsch and his team emerged from the shed with a tiny free-piston engine that made 10 HP.

Eventually, Ford gave the project its blessing, and Klotsch expanded his ideas into more powerful, more practical engines.

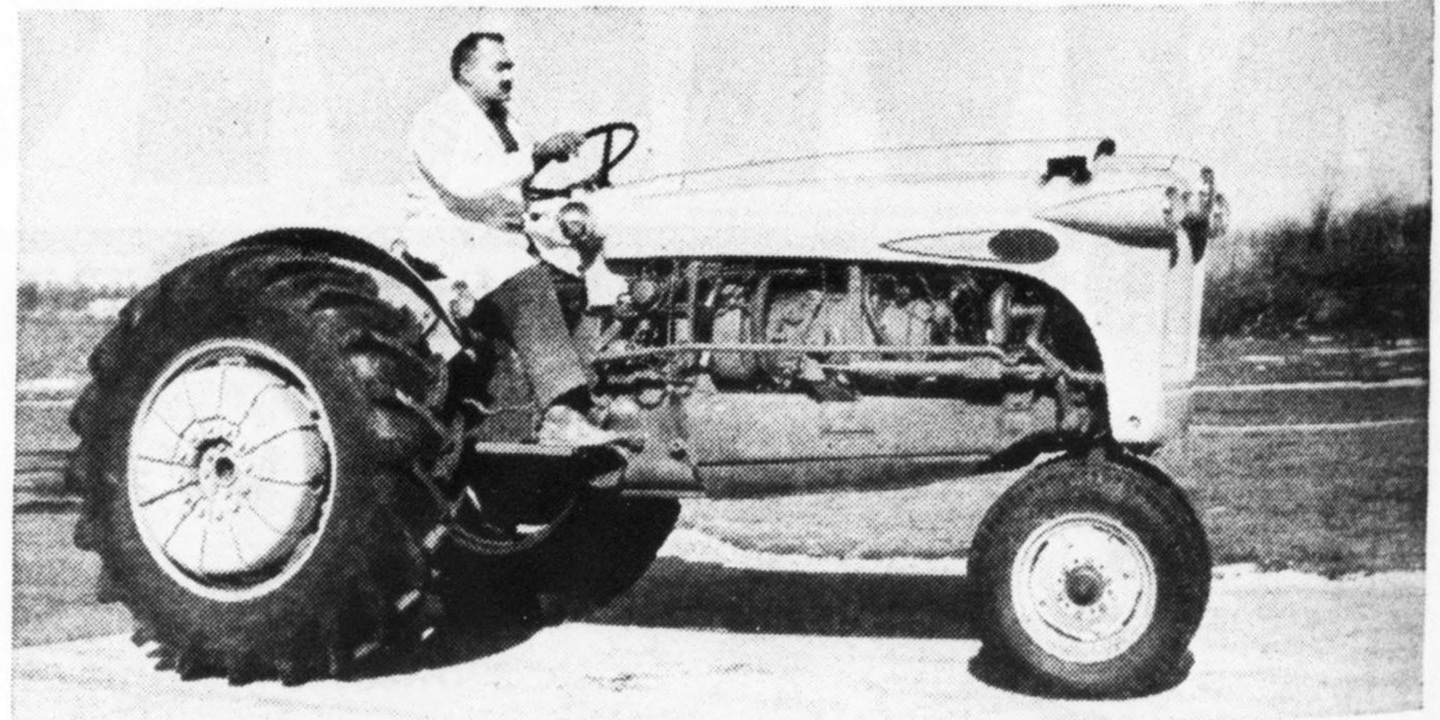

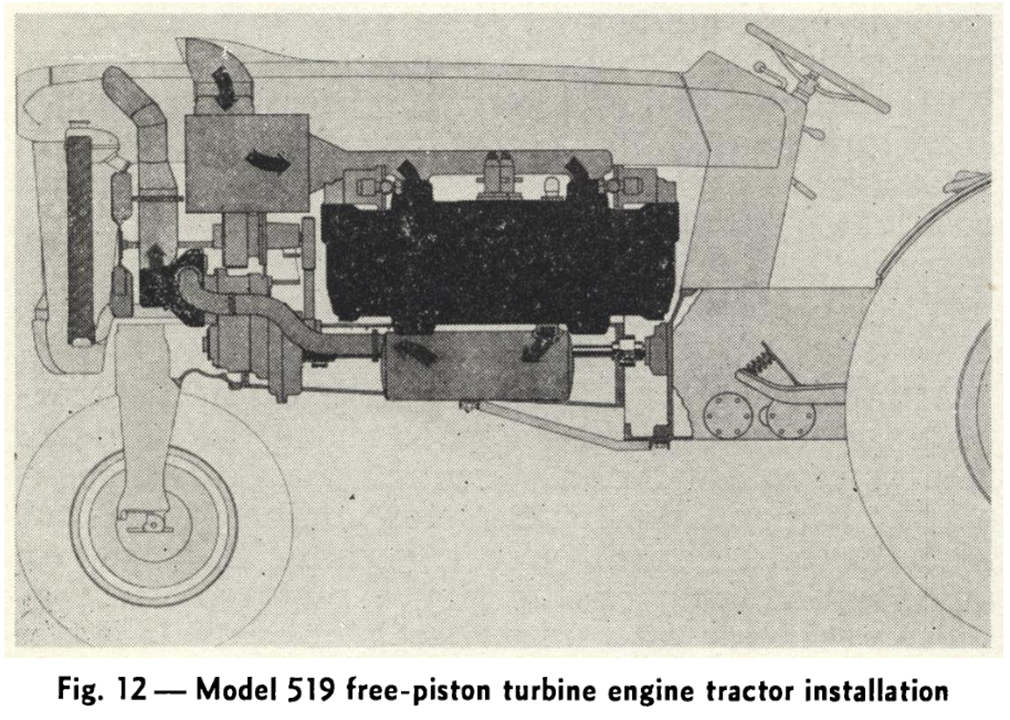

In March 1957, Ford presented its new engine in a Ford 900-based tractor that it called the Typhoon. The engine onboard the tractor worked like an opposed-piston engine, only it didn’t have a crankshaft. Here’s how Popular Science describes the operation of Klotsch’s engine:

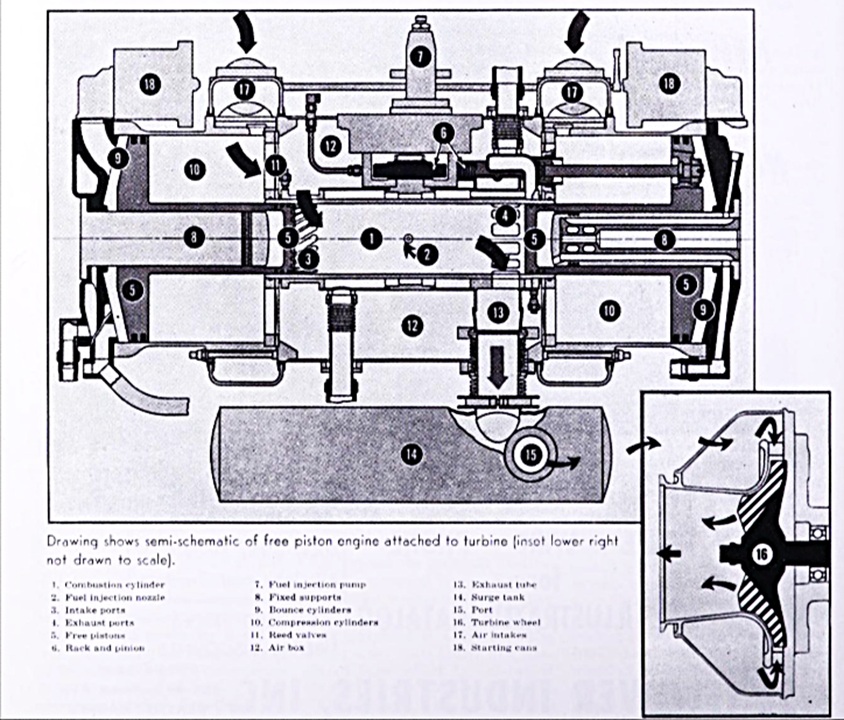

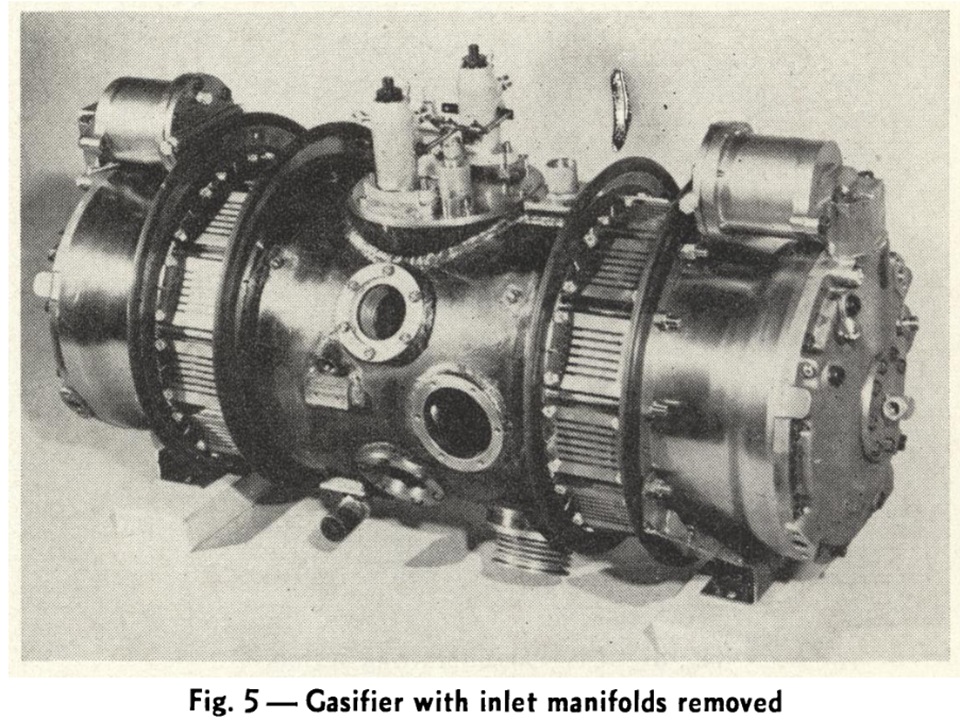

When you open the hood, you see an engine like no other on earth. It has two basic parts: an opposed-piston diesel, called a “gasifier,” which has no crankshaft or connecting rods, and a five-inch turbine, driven by the hot diesel exhaust. The horizontal diesel cylinder is shaped like a squared-off dumbbell and the pair of opposed free pistons can be likened to squared-off mushrooms whose stems face each other in the dumbbell grip. The pistons are forced together initially by a compressed-air starter, and fuel is injected into the superheated air between them. Driven apart by combustion, they bounce against cushions of trapped air at each end, and are driven together again to start another cycle.

‘The big outer ends of the pistons—the “mushroom caps”— do another job on the inward stroke. They force compressed air into a chamber around the cylinder. This blows through the cylinder when ports are cleared by the outgoing pistons, scavenging the gases and supplying pure air for the next combustion. Both gases and scavenging air are led to a “surge tank” that evens out the pulsations of the engine and delivers a continuous flow of gas to the turbine. In a straight diesel engine, the scavenging air is thrown away and its heat lost through the exhaust. This is one reason why Ford engineers believe the new engine may surpass even the diesel in fuel economy.

The mixed-in air does more than scavenge. When the gas hits the turbine blade, its temperature runs about 950° F. and this is important. It means that the turbine can be made of ordinary stainless steel, while the “pinwheel” for straight gas turbines requires expensive alloys to resist much higher temperatures. The “straight turbine” pinwheel currently costs about as much as an entire automobile piston engine, while Paul Klotsch figures that in orders of 60,000 Ford should be able to get its free-piston turbines for $18 each. Even if other things were equal, this might be the determining factor in any race between the two new power plants.

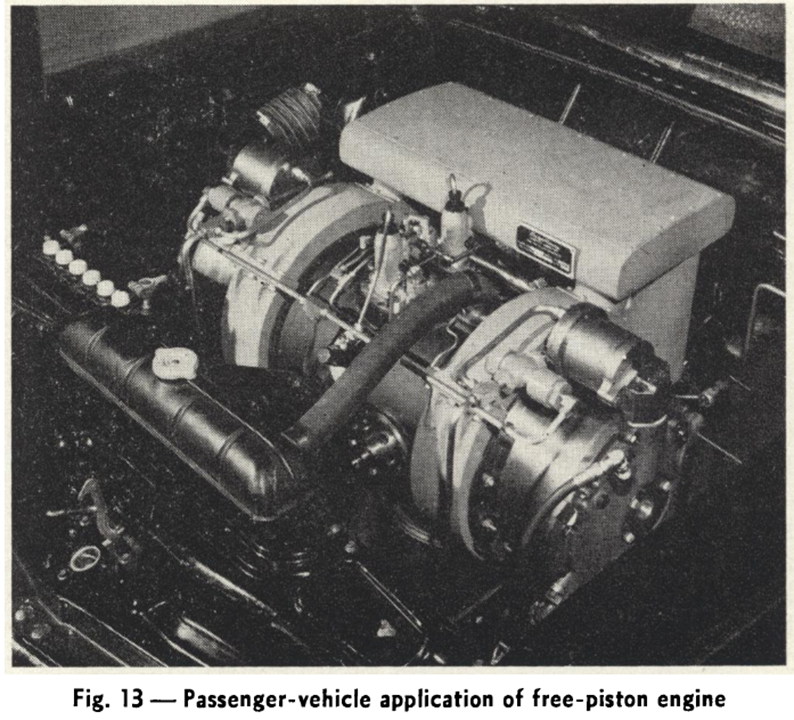

Ford’s free-piston engine produced 15 PSI to 25 PSI of pressure, which was enough to drive the turbine to 10,000 RPM when idle or 45,000 RPM when under load. The turbines were capable of 100 horsepower, but Ford’s engineers capped them to 50 horsepower. A muffler wasn’t required for noise reduction, and Ford said that the turbine had a whine that was noticeable only at idle speed.

The free-piston engine never directly drove the tractor. Instead, all the engine did was use its exhaust to drive the turbine. That turbine then runs double-reduction gears mated to main and auxiliary drives. The main drive, which required a reduction of 5,600 to 1, just drives the wheels. The auxiliary drive operated the hydraulic pump and power take-off.

The free-piston gas generator was thought to be even more of a holy grail than the gas turbine. Ford engineers touted their engine as being more responsive than a pure gas turbine, from Popular Science:

“This engine also solves the acceleration problem that bothers the gas turbine,” said Ray Miller. “In the built-in fluid drive of the gas turbine there is an awkward time lag while the power turbine catches up with the compressor turbine. But the free piston, with its variable compression ratio, is so responsive that it accelerates even faster than a conventional gasoline engine. The free piston-turbine combination also has the equivalent of compression braking, for if you take your foot off the pedal and reduce gas pressure, you create a partial vacuum at the turbine and get a fast braking effect.”

The Ford Free-Piston’s Promises

Ford’s engineers saw the free-piston engine as a replacement for diesel engines, especially those working in agriculture. That’s why Ford built three tractors with these engines. Ford’s pitch continued by saying that its engine was the future because it was lighter than comparable diesels, had fewer parts that could wear out, had no connecting rods, had only one injector, and could even be run on a variety of fuels. That last one was important for this engine, as it was thought that farmers could run this thing on whatever fuel they had sitting around.

Engineers then tried to sweeten the idea further by stating that you wouldn’t even need a battery because the engine uses an air start and automatically stores air for the next start upon engine shutdown. A vacuum pump was also onboard for starting.

The Ford free-piston engine, like many other free-piston engines, worked on the two-stroke principle of firing on every cycle. Free-piston engines also had an interesting relationship with lubrication. Since the engine didn’t have a crank, valves, connecting rods, bearings, or anything of that sort to worry about, the Ford engine featured a pump that fired oil directly at the pistons.

General Motors was perhaps even more ambitious than Ford. While Ford saw free-piston engines doing the work of diesels, General Motors bolted its own take on the concept into the XP-500 concept car, but that’s a story for a different day. Ford also put a free-piston engine into a car. Sadly, I didn’t find out any further information outside of a passing mention in the SAE paper on the tractor:

Ford wasn’t the only one trying to reinvent tractor propulsion. In 1959, Allis-Chalmers produced an experimental tractor that used 1,000 fuel cells to generate electricity to drive the tractor.

You Can’t Buy A Free-Piston Tractor Or Car Today

In 1959, Klotsch published a paper titled Ford Free-Piston Engine Development, which was presented to the SAE Texas GulfCoast Section. In the paper, Klotsch said that the engine was just as economical as a diesel engine but as responsive and as flexible as a gasoline engine. Ultimately, while Ford continued both its free-piston research and turbine research, the Ford free-piston tractor was merely an experiment for research.

Free-piston engines did not turn out to be the future as the press of the 1950s promised. Some challenges presented themselves over the decades. The free-piston engine’s strength – its lack of a crankshaft – presented an inability to directly drive a car’s accessories. Instead, parts like an air-conditioner or alternator would have to be driven from the turbine.

Then, there was what Newcastle University noted earlier, that controlling the stroke and compression ratio was difficult, as every combustion cycle was slightly different. In theory, free-piston engines can achieve impressive efficiency, even for modern standards. However, as Autocar notes, figuring out exactly where the pistons are in their strokes has long been a problem.

Ford’s solution to this problem was a rack-and-pinion system that linked the pistons together. But even Ford’s research on its rather complex engine eventually reached a dead end.

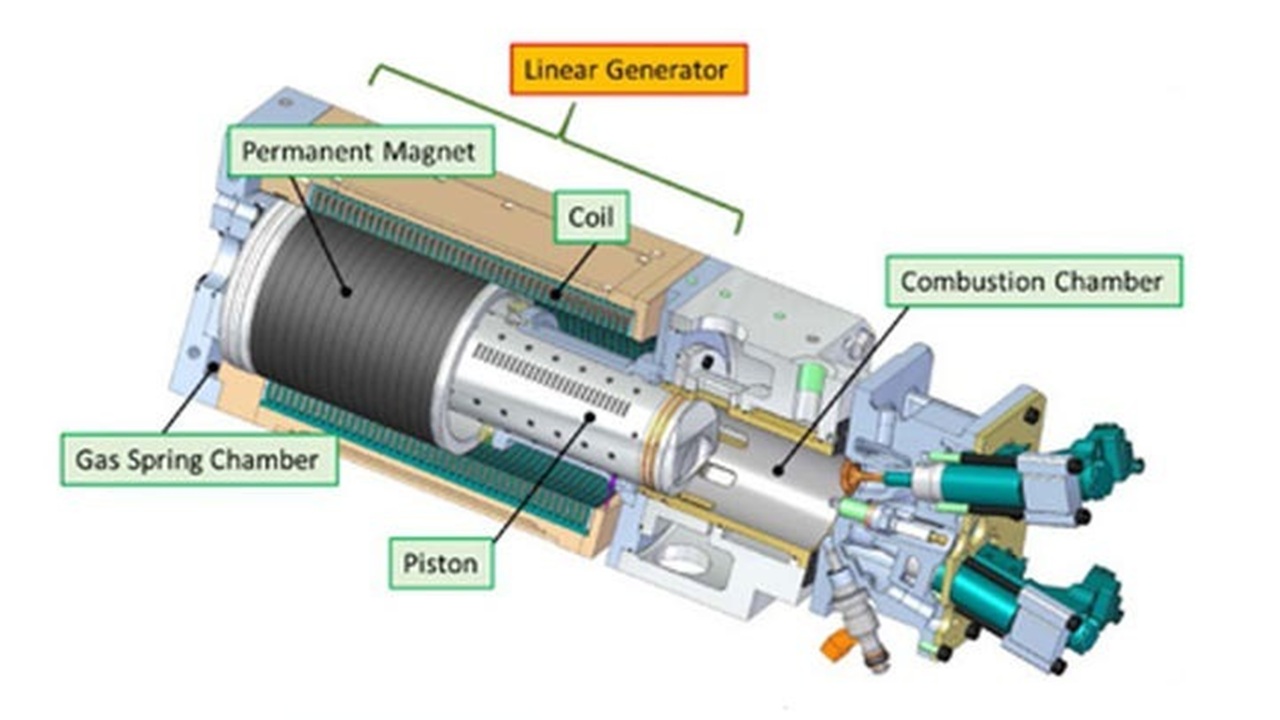

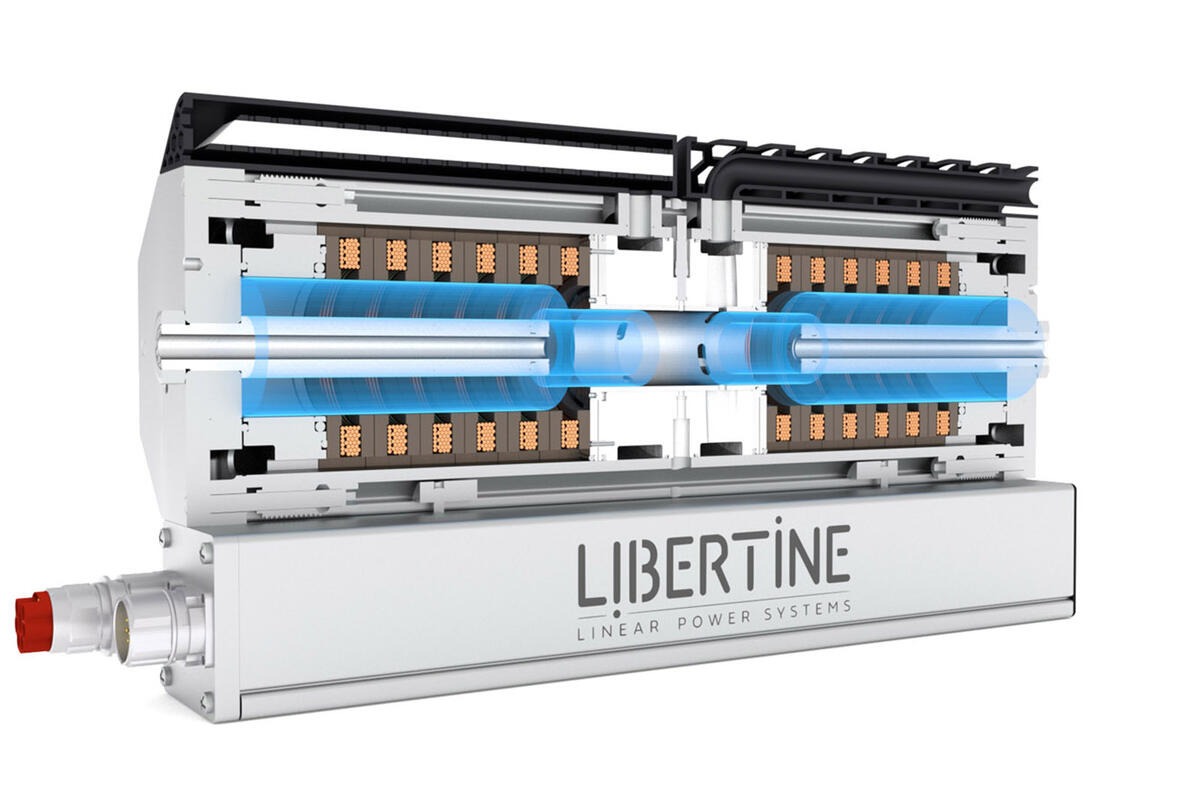

Thankfully, free-piston development never really died. Here in the 21st century, companies like Toyota and Libertine claim to have cracked the code to a practical small free-piston engine by using modern technology.

Toyota’s free-piston engine, which it teased in 2014, didn’t drive a turbine. Instead, it functioned as a two-stroke electrical generator. In using modern technology, like direct injection and electric valves, to tweak a nearly century-old idea, Toyota claimed efficiency of 42 percent and an output of 10 kW.

Newcastle University and West Virginia University have also worked on modern free-piston designs. Yet, you still cannot buy a tractor or a car with one of these engines, despite engineers tweaking this basic engine design for longer than a century.

I am not sure if free-piston engines will ever be the future. But I am sure that it is amazing such an engine exists in the first place. I get why engineers keep researching them, too. Imagine an engine with fewer moving parts, better efficiency, and possibly lower build cost. With proposed advantages like that, I’m not at all surprised that Ford, General Motors, and even Toyota looked into the technology.

Top graphic image: Ford

Seems like a needlessly overly complicated way to fix the solved problem of delivering hot, pressurised gas to a turbine. How is this better than having a compressor turbine delivering pressurized air to combustion pots which deliver that hot, pressurized gas to a turbine like a regular turboshaft engine?

I’ve heard that some manufacturers put free piston engines in their cars today; you just have to wait for the rods to fail.

Would they be useful as range extenders for phev type vehicles?

That does appear to be one of the proposed applications for a free-piston engine today!

That Toyota engine looks intriguing. It looks to use the back and forth motion of the piston to directly induce current in wire loops surrounding the piston bore. That’s a lot simpler and more compact than a typical generator. Might be harder to control the motion than with a rotating mass but perhaps feedback from the coils could help with that.

Very cool article, I didn’t know about Ford’s free-piston efforts. GM had a similar free-piston engine + turbine program that they installed in one of the “Firebird” concept cars. The engine was called the “Hyprex” and had a similar opposed-piston 2-stroke design to what’s shown here, with both bounce chambers and intake compression volumes on the pistons as well as the combustion chamber.

https://www.sae.org/papers/gmr-4-4-hyprex-engine-a-concept-free-piston-engine-automotive-use-570032