Aerodynamics is vitally important across multiple vehicle industries today. Making a car slide through the air is one of the best ways to stretch out its electric range or help pump up its fuel economy. For decades, the trucking industry has also been making semi-tractors more slippery, because even small gains in efficiency are huge for truckers putting on hundreds of thousands of miles. But this wasn’t always the case. Trucks used to be inefficient bricks, and in the 1960s, one man thought he had the solution. This is the Paymaster, a futuristic wedge-shaped semi that promised up to 40 percent better efficiency than other trucks before most truck manufacturers even cared about aero.

The images in this story come from the epic repository built by Dick Copello. Dick was a car hauler for around 30 years, and he’s collected a treasure trove of photos from his trade. His Flickr page depicts in beautiful detail how truckers have hauled cars and other goods throughout history. The Flickr page is still active, too, so if you like big rigs, I recommend giving Dick a follow. Likewise, if you’re looking for some great truck reading, he’s written the encyclopedia of car hauling in American Car Haulers.

So many branches of modern transportation history snake their way back to the infamous multiple oil crises of the 1970s. This era, included more than just fuel shortages and high fuel prices but also depressed consumer confidence, an enhanced attention to emissions, and amplified concerns for vehicle safety. The auto industry responded to the times with rapid downsizing and a heavy focus on increasing fuel economy. Meanwhile, the nation took serious measures to cut back on the haze of pollution that hung over cities. One of the ways America curbed its thirst for fuel was through the now-infamous “double nickel” 55 mph national speed limit.

The trucking industry also had to react to the times. Diesel fuel pricing spiked hard, which spelled bad news for the industry. So much of America moves in the trailers hitched to the backs of semi-tractors, and high fuel prices can threaten to clothesline the industry. According to a 2008 U.S. Energy Information Administration report, the price of diesel was $0.36 per gallon in 1978, rising by well more than double to $0.97 by 1981. An additional curveball came from the fact that the price of diesel rose and then stayed high, which forced manufacturers to scramble to find solutions.

As I wrote last month, Kenworth responded to the difficulties caused by the oil crises with the 1984 Kenworth T600, the truck that Kenworth claimed was the first to be built from the ground up around aerodynamics.

The world of trucking before the era of the aero semi was one where cabover semis ruled. The Motor Carrier Act of 1980 helped advance deregulation of market entry, and the Surface Transportation Assistance Act of 1982 set national standards for total length and weight. Before these landmark acts, truckers had to deal with state-specific restrictions on total length and weight, which often limited the size of the loads they could carry, and thus, how well they could be paid. Of course, this was also less efficient for moving goods around.

The era of regulations like 55-foot overall length restrictions had pushed the cabover truck to its reign over American trucking. By piling the cab on top of the front axle and the engine, the tractor took up minimal space, allowing for a semi-trailer of maximum length to increase loads and profits. But this had disadvantages. Cabovers looked awesome, but their rides were known for being harsh. These trucks also had the aerodynamics of a department store on wheels. Servicing these trucks also got fun. If you had a sleeper and tilted the cab to service the engine, anything not nailed down was liable to get thrown about.

America did have conventional semis — trucks where the engine and front axle sit ahead of the cab, giving them a “long nose” — on the roads back then, but buying the more comfortable truck often meant limiting your load.

The poor fuel economy of cabover rigs, which often got as low as mid-single-digit mpg, was easier to swallow when diesel was cheap, but the 1970s changed the game. While Kenworth often gets credit for putting aero at the forefront of semi-tractor development, one man tried solving the problem of poor semi efficiency back in the 1960s. His creation would look like no other truck on the road, not at least until the Tesla Semi, anyway. This is the Paymaster, the work of one man, Dean Hobbensiefken.

The Self-Taught Engineer

The book We Ask, Why? by Donald M. Alanen, tells the story of Dean Hobbensiefken, and it sounds like something that could have been ripped from the script of a film. Alanen says that he was a personal friend of Hobbensiefken, and he interviewed Hobbensiefken about the development process of the truck.

Alanen’s book notes that Hobbensiefken, who lived in Lyons, Oregon, outside of Portland, was a self-taught electrical engineer and mechanical engineer who operated a truck fleet. When he wasn’t trucking, he also built racecars and even flew a plane. Hobbensiefken drove his truck during the day to make money and then repaired his own fleet after his shift was done. He was comfortable spinning a wrench and firing up a welder. In 1969, Hobbensiefken decided to tackle the awful fuel economy of semi-tractors. After all, as an owner-operator, he was acutely aware of how expensive it was to fuel his rig.

Hobbensiefken’s idea called for a new kind of semi to be built from the ground up to be aerodynamic. This slick four-axle combination truck could be 40 percent more efficient than the brick-like cabovers that ruled the road in 1969 and still carry a 50,000-pound payload.

Alanen says that Hobbensiefken took his idea to Freightliner and was allegedly told by company engineers that his ambitious idea could not be done. Remember that truck manufacturers were still hamstrung by length restrictions. Hobbensiefken was calling for a truck that took up roughly the footprint of a cabover, but with substantially better aero.

Unable to get interest from the big truck manufacturers, Hobbensiefken turned to just building his dream truck by himself. Hobbensiefken fired up the same shop that he used to repair trucks to build a new one, all without the aid of computer design or even a formal degree. Assistance in building this new truck would come from materials sourced from a local trailer manufacturer.

According to Alanen, Hobbensiefken spent pretty much his entire days dedicated to trucks, because now, after he was done driving and repairing his existing trucks, he then made drawings for his new truck. It would take Hobbensiefken two years to complete the first Paymaster, a name that Hobbensiefken had chosen because the truck was so efficient that it “paid” its owner in low fuel costs and ease of maintenance every day.

The Truck Of The Future

The Paymaster had two key elements. The first was a ridiculously low drag coefficient for a semi. According to Alanen, the truck had a coefficient of drag of just 0.43, which was said to be 40 percent slicker than other trucks in 1971 when the Paymaster was completed. To put that into perspective, this was a semi-tractor with the same drag coefficient as a second-generation Ford Explorer.

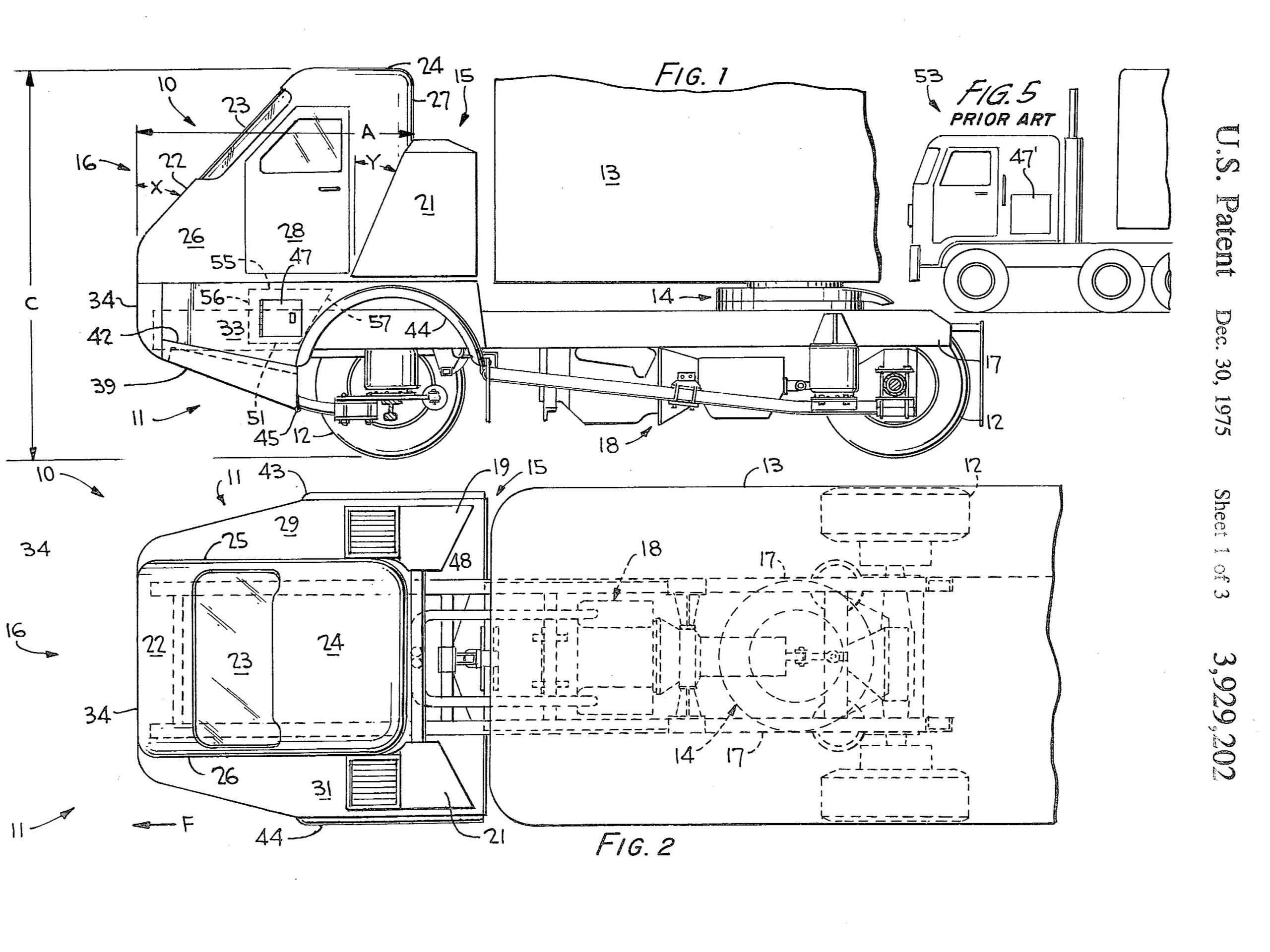

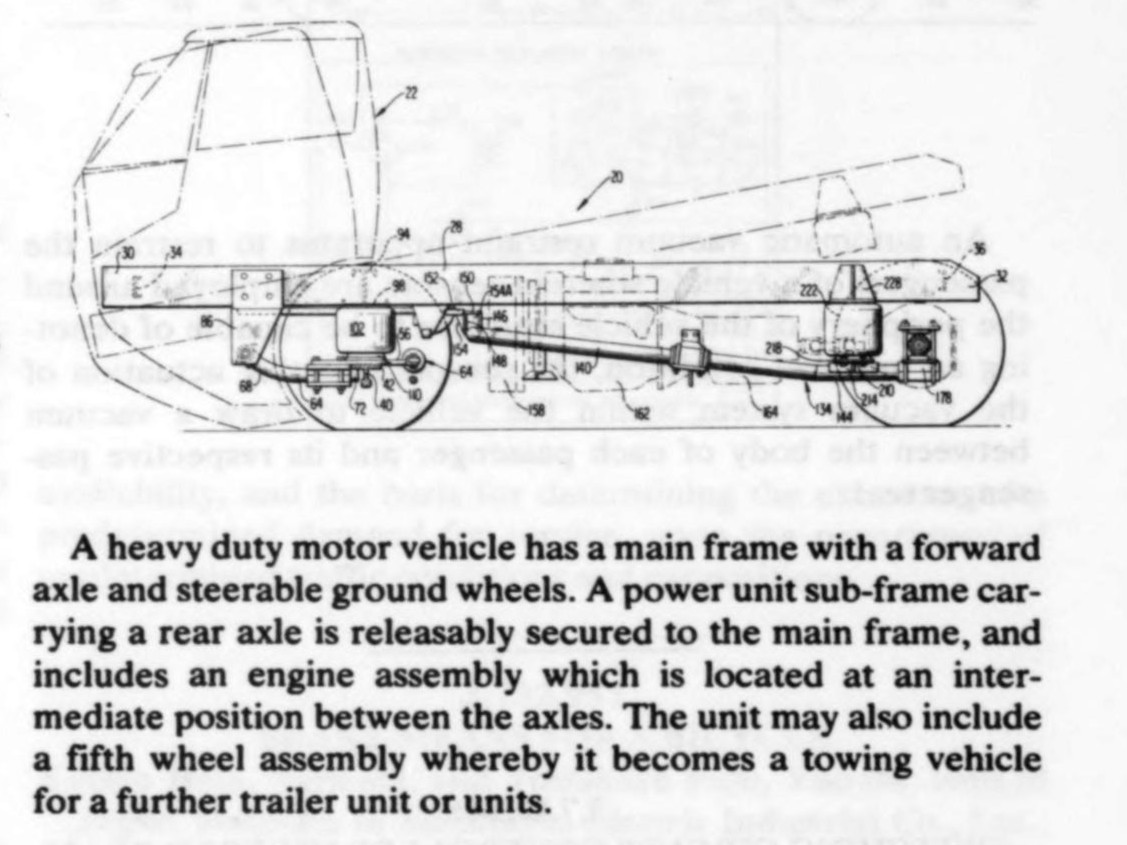

Hobbensiefken created a distinctive wedge-shaped body that used spoilers to redirect air. This body couldn’t just be plopped down onto any old truck, and so Hobbensiefken created his own chassis, too. Since Hobbensiefken fixed trucks, he took this opportunity to design his truck to make servicing easier. The Paymaster had a main chassis, plus a subframe that the entire drivetrain was mounted to. This subframe was designed to be easily disconnected so that a mechanic can wrench on the drivetrain without a cab in their way.

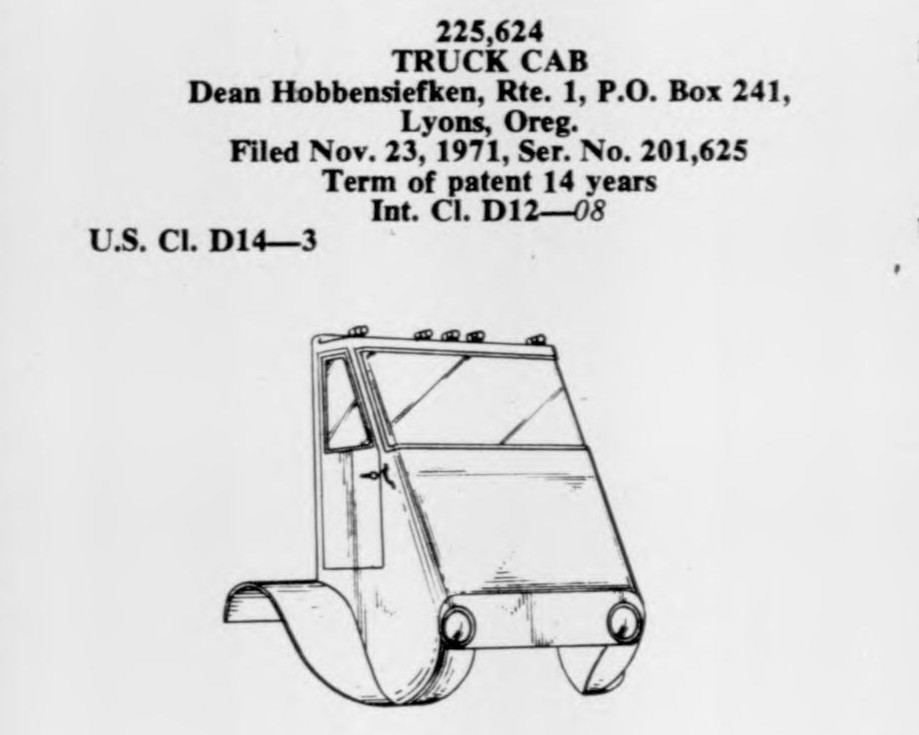

Hobbensiefken’s work was rewarded in the form of 26 patents covering everything from the cab design to the aforementioned engine and transmission subframe. These patents reportedly cost Hobbensiefken $50,000 in the early 1970s. Hobbensiefken, who passed in 2011, used to run paymastertruck.com, where he explained his truck’s additional features:

1. Improving the fuel mileage by reducing the demand horsepower on the engine by lowering the aerodynamic drag, lowering the rolling resistance, lowering the accessory loads and friction losses.

2. Lowering the maintenance cost of the truck through the simplification of systems and the use of long life low maintenance components. Also by designing everything possible so that the components could be easily worked on and repaired or replaced in the least amount of time to reduce shop labor costs.

3. Improving the ride for the driver and lowering the noise levels. The vehicle has air suspension on each axle including the steering axle. This not only improves the ride for the driver but lowers the repair cost in maintaining the cab and chassis.

4. The versatility of the truck was improved by the unique chassis design that along with a 62 in. sliding fifth wheel allow this two axle tractor to pull a semi and haul the same net payload as a three axle tractor. The tractor can also pull standard double trailers.These design guidelines resulted in a vehicle that through scientific testing showed substantial improvements in ride over other trucks. The resulting fuel mileage was increased 40 % to a documented figure of 7.0 mpg while still hauling the same payload as a three axle tractor.

What made the Paymaster impressive was that it didn’t do anything special under the cab. The prototype’s original engine was a Ford gasoline V8. Then, Hobbensiefken swapped it out for a Caterpillar 3208 10.4-liter V8 diesel rated at 225 HP. It was with this engine that the Paymaster got 7 mpg compared to the 5 mpg the typical semi got back then.

Sure, 2 mpg isn’t much, but when you compound that over the course of 500,000 miles, it really adds up.

The Paymaster Hits The Road

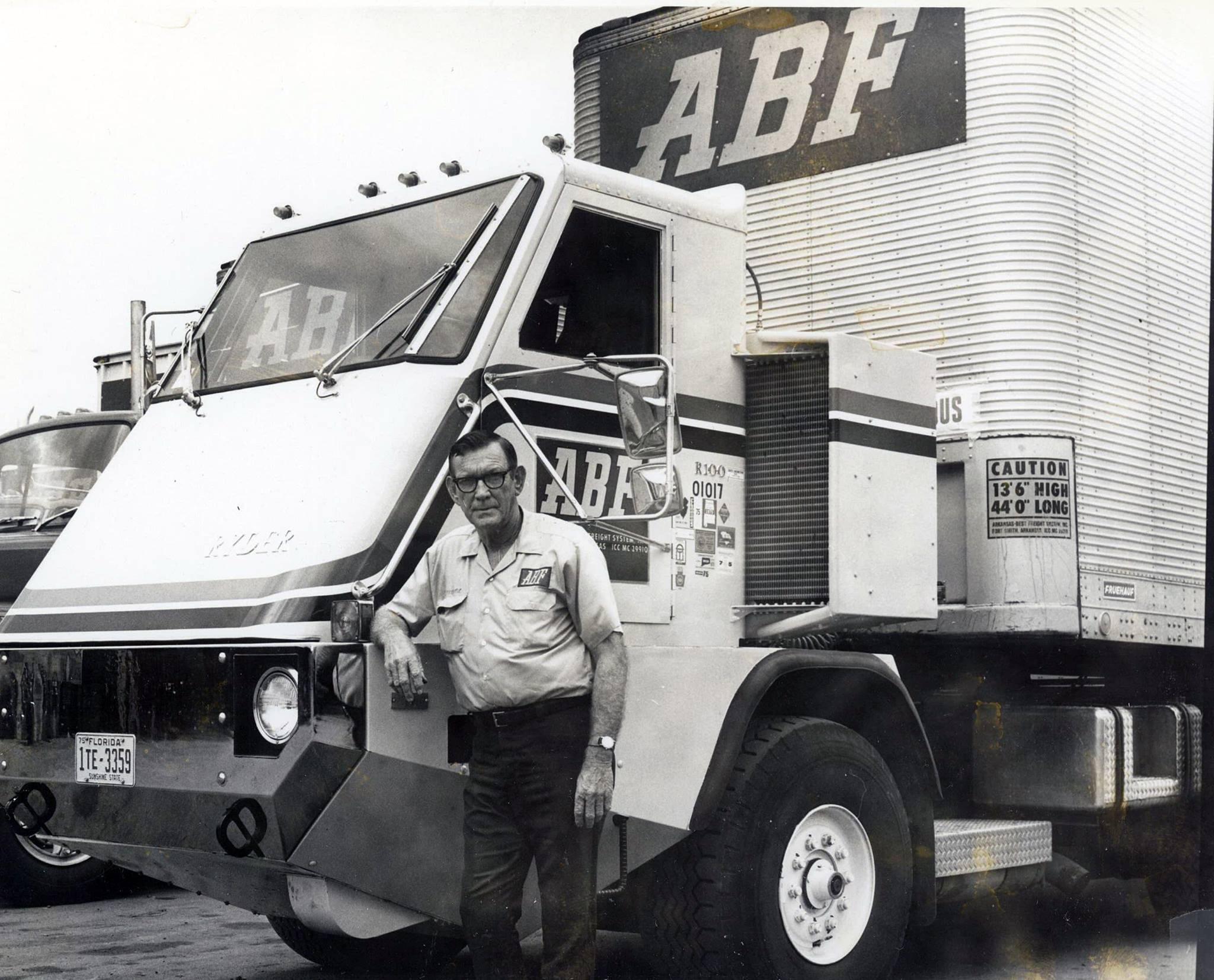

Hobbensiefken displayed his creation to the public in 1972, and at first, there was a lot of buzz for the truck. The timing was unfortunately perfect, too, as the first oil crisis was right around the corner. Alanen writes that practically every trucking trade journal covered it, and the truck even briefly got attention from Boeing. Reportedly, a member of the Nixon administration even called Hobbensiefken to get the scoop on the truck.

However, the truck never got mainstream news attention, and talks with the federal government and Boeing went nowhere. America’s large truck manufacturers, including Freightliner, Peterbilt, Mack, and Kenworth, were reportedly not interested in helping Hobbensiefken make the truck. How could seemingly everyone say no to a truck that got 40 percent better fuel economy?

Alanen’s book suggests that the problem was that Hobbensiefken was pretty much a one-man show. Sure, he had a prototype truck, but he had no real capacity to put the truck into mass production. So, any company or government that got in bed with Hobbensiefken would have had to supply him with a factory, tooling, employees, and all of the rest of the groundwork necessary to produce his truck design.

Alanen writes that the Paymaster would soon fall into obscurity. Hobbensiefken continued driving the sole example and continued to demonstrate its awesome fuel economy, but it would never go into production.

(The video below shows a 1974 Ryder Paymaster R-100 in the Iowa 80 Trucking Museum)

Winds of change came when Jim Ryder of Ryder Systems of Miami, Florida wanted to build the truck of the future. This was a big deal as Ryder was the largest fleet lessor in America. Reportedly, Ryder’s original idea called for getting glider kits — a truck cab and chassis with a front axle; the powertrain and drive axles are provided by the buyer — from truck manufacturers, but had no luck.

In 1974, Ryder Systems hired Hobbensiefken as a consultant and reportedly started development of the second-generation Paymaster. By now, Hobbensiefken had been working on refining the Paymaster for a decade, and he joined a former Ford heavy truck engineer to refine the Paymaster design for Ryder.

Reportedly, Ryder contracted the construction of the design out to Hendrickson International of Chicago, Illinois, which built 10 second-generation Paymaster trucks between 1974 and 1975. Ryder’s version kept Hobbensiefken’s innovative features, including the aero and the mid-mounted removable drivetrain. As Alanen’s book continues, the Paymaster allegedly impressed in testing, with a quieter cab, better stability, and better braking than pretty much every other truck on the market. Oh yeah, one of these hit a world speed record too:

Hobbensiefken’s website continues:

Over two million dollars was spent in developing and testing the Paymaster truck design and there were over twenty very detailed and scientific testing programs that the vehicles underwent. These tests included such things as wind tunnel tests at the University of Maryland, scientific ride analysis by Bostrum Seat Co. and scientific structural analysis by A. O. Smith Co.

Detroit Diesel Allison, Cummins Engine Co. and Firestone Tire Company also conducted lengthy and detailed testing on the vehicles. In one test, a second generation truck tractor was driven 24 hours a day, seven days a week on the Firestone Tire Co. test track at Fort Stockton, Texas. It was run a total of 39,295 miles pulling loaded double trailers at a gross combined weight of 109,000 pounds at 60 mph. The results of this test was that this Paymaster truck got 19.8% better fuel mileage than a Mack truck running at a gross weight of 107,000 pounds.

Improvements in fuel mileage were the result of reducing the demand horsepower on the engine at normal operating speeds. A standard truck of the period required about 235 hp. to run 55 mph and the Paymaster design with reductions in aerodynamic drag and rolling resistance, along with reductions in the accessory loads, cooling fan power and friction losses was reduced 100 horsepower to only 135 hp at 55 mph with the same payload. Along with these reductions in horsepower demand on the engine, the proper gearing had to be chosen so that the engine operated at its most fuel efficient RPM at the desired cruise speed.

According to The Complete Encyclopedia Of Commercial Vehicles, which was published in 1979, the Paymaster was pitched as being available with a Detroit Diesel 6-71, a Detroit Diesel 6-71T, a Detroit Diesel 6V-92TTA, a Detroit Diesel 8V-71T, or a Cummins VT 903. A Fuller RT910 was the primary transmission choice, and drivelines were by Spicer and Rockwell. In other words, there was supposed to be a Paymaster for all kinds of drivers. There were even sleeper models.

Sadly, I could not find any cab interior photos, but stories suggest that the cab wasn’t the best for long-haul operations.

The Paymaster Struggles To Find Interest

Unfortunately, as Alanen writes, not even a frugal semi could beat the tough 1970s. The few operators of the Ryder Paymasters began returning their trucks to Ryder as they couldn’t afford to operate anymore. Ryder itself responded by canceling the program. Hobbensiefken was left once again without anyone to build his truck.

Hobbensiefken’s work continued through the rest of the 1970s and into the 1980s as he built more prototypes in Oregon and tried to sell the Paymaster idea to anyone who would listen. Alanen’s book says that Hobbensiefken tried unsuccessfully to pitch the Paymaster to the military as well as a group with big funding from Saudi Arabia. All while this was happening, firms like White and Kenworth had begun production of their own aero trucks that still weren’t as slippery as the Paymaster. But unlike Hobbensiefken, those manufacturers had the money and the facilities to build those trucks. Some of Hobbensiefken’s last pushes to sell the Paymaster happened in 1984.

Ultimately, all of Hobbensiefken’s plans didn’t succeed in putting the Paymaster into mass production. In the end, Hobbensiefken says that just 14 Paymasters of all kinds were built between 1971 and 1980. Since then, surviving trucks have ended up in private hands and inside trucking museums.

On his website, Hobbensiefken took a pretty humbling approach to the whole situation, admitting that he might not have made all of the right choices and that timing also often worked against him. Could the Paymaster have been successful if Hobbensiefken had more money or had pitched the truck in the 1980s rather than the 1970s? Maybe. However, Hobbensiefken indicated on his website that he didn’t regret the whole adventure and that he found the whole thing fun.

That’s a great way to look at it. I think it’s also noteworthy that he achieved a dream that few have. Sure, only 14 of these trucks were ever built, but they did exist and, at least by the accounts I’ve read, they largely lived up to the promises. Maybe this truck failed to revolutionize trucking, but the Paymaster still goes down in trucking history as weird and innovative.

Thanks for this bit of automotive ephemera Mercedes! 🙂

Pity he never got it further. Imagine if a gen 3 was made, or had the later generation diesels, like the detroit series 60 in it, probably wouldve gotten even better fuel economy

Go on the highways near me, and nearly every 40 tonner has a faring behind the cab to improve the aerodynamics of the trailer.

With curtain sided trucks you can sometimes see where the vortexes generated land, usually about three quarters down the trailer, because that is where the curtains wobble the most.

This explains all those little Tonka™ trucks I see in the toy sections of antique shops.

Thanks for the enlightenment!

I saw one of these, in Ryder livery, in a private collection in Eastern Ohio about 10-15 years ago. I was curious as to how many were made. Thank you!

I’m not crazy about how it looks like it’s designed to just run right over the top of any car that gets in the way.

Otherwise it has a nice Oshkosh vibe to it.

If Toecutter was into trucks 😉

I like big rigs and I cannot lie.

“2 mpg isn’t much”

It all depends where you start, and is why fuel economy is better expressed in the inverse. Normally this is in “l/100km” but since we started in obsolete, I shall continue.

If you start at 28mpg and go to 30mpg it isn’t much.

28mpg is 3.6gallons per 100 miles

30mpg is 3.3gallons per 100 miles

So the saving is 0.3 gallons of fuel for every 100 miles. Nice but not earth shattering

But for a truck doing 5mpg it is huge.

5mpg is 20.0gallons per 100 miles

7mpg is 14.3gallons per 100 miles

So the saving is 5.7 gallons of fuel for every 100 miles. Gulp!

A saving of “x” gallons per hundred mile is always a saving of “x” gallons per hundred mile, no matter what you are comparing it to.

“Goes 40% farther on a gallon of fuel”

Seems impressive to me.

An extra 2mpg isn’t impressive if you leave out the total mpg.

Agreed!

Gallons per mile may be a clearer way of expressing differences in fuel efficiency than miles per gallon… but either way, percentage differences are even better at expressing relative improvement.

Was coming down to make this exact point. At single digit MPG, a single digit increase is huge! It’s like saying going from 1 to 2 mpg isn’t much when it’s cutting fuel use by 50%. Even fractions are important in this area.

I read that whole post twice before I realized it wasn’t a really obscure song parody.

Something doesn’t sound right.

If these trucks were supposedly as efficient as he claimed, it would be like printing money for everyone involved. Why did the small group of 2nd gen trucks get returned by their operators? At the end there, he claims that maybe the timing was bad, but having the most efficient trucks during an oil crisis is the BEST time.

People LOVE a underdog story like this, but we are only seeing one small part of the story. I am not discounting the stubbornness and arrogance of established companies who are afraid of losing their dominance, but seems like something would have come from his designs if they were indeed as impressive as claimed.

It sounds like he was unwilling to liscense the designs to someone else to build. Going from 225 to 125 hp at speed is a truly ridiculous achievement in the era, so really this feels like he wasnt willing to let go of the wheel.

For a low production truck they were surprisingly durable- Dean’s original truck from the early 70s was still seen running around Portland in the late 90s. An owner operator couple bought one of the ones Dean built after the Ryder deal died and put 2 million miles on it, IIRC a trailer company in Kansas still uses it.

I saw a Paymaster at the PNW Truck Museum in the early oughts and the LSR Paymaster was also there for the truck show. For the record Lyons Oregon is closer to Salem than Portland, and Powerland in Brooks is just north of Salem, so a quick blast down I-5 gets you to the truck museum, and all the other museums, and Lyons is a half hour jaunt down highway 22.

They still have a Paymaster at Powerland, guess I should’ve paid it a visit when I was down there last weekend.

They also have a miniature Freightliner, and I want to see the Caterpillar museum. I’ve ridden past on the Monster Cookie ride more often than I’ve visited.

TIL about the Monster Cookie ride – a long Springtime group bike ride on the Willamette valley floor around Champoeg sounds really nice, but I’m definitely not currently capable of 100km worth of pedaling!

Lyons, Oregon isn’t really considered outside Portland. You’d be better off writing it is outside Salem as it is east and a bit south of the capital.

Everything in Oregon is outside Portland now. Except Ashland, which is outside San Francisco and Bend which is outside Los Angeles.

Sadly Bend is the fastest growing Californian city. While I’ve lived less than a decade in Bend, I’ve lived in Oregon over 30 years so I’m qualified to grump

He made 14 trucks more than the rest of us.

Hats off to him and glad he enjoyed it (as opposed to dying bitter and penniless).

Those would still look futuristic on the roads today

*stamp of approval* Daily.

Pretty sure this was the inspiration for the little (6″ long or so) Tonka dump truck I had in my sandbox as a kid.

They certainly made more than 14 of the Tonka trucks. I wonder if he got a small licensing fee?

Tonka may be the biggest dump truck manufacturer in the world.

Wow. Definitely not an area of vehicular history I know anything about, so I really enjoyed that chance to learn about it. Glad you found this Mercedes!

My first thought was “AI generated photo of a 1969 Tesla Semi”