A hurricane is one of the scariest weather events a person can experience, the worst of which have winds well over 100 mph and an overwhelming storm surge. One of the coolest tools in learning how hurricanes work to improve research and forecasting is the hurricane hunter. These planes, and their awesome crews, fly directly into storms in aircraft with specialized equipment, allowing researchers a direct look into the mechanisms of some of the most damaging storms on the planet. Here’s how they work.

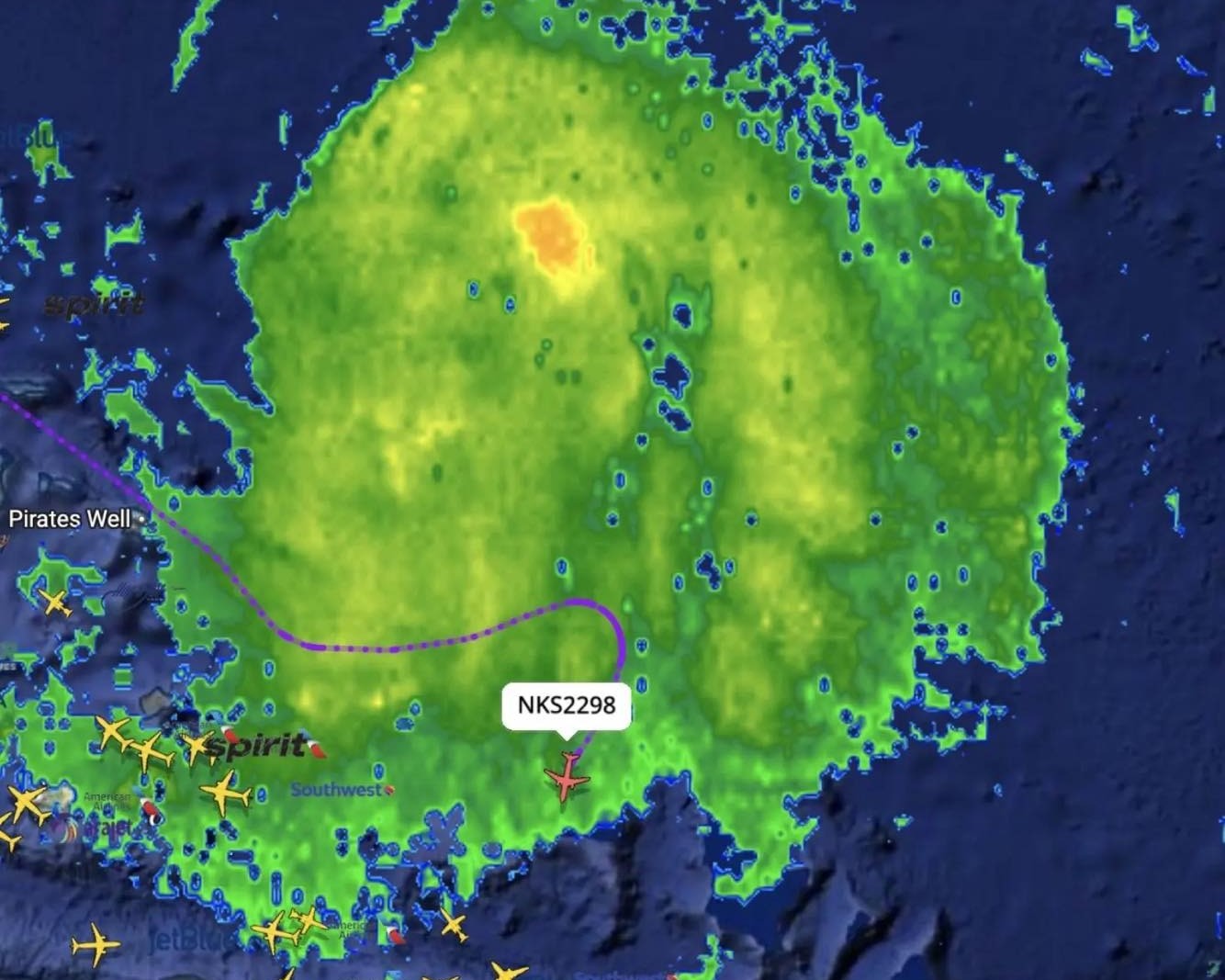

The subject of planes flying in and around hurricanes seems to be on the minds of many people right now. If you’re a player of SkyCards, you’ve maybe even seen a National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration P-3 Orion flying toward a storm when every other aircraft was avoiding it. Or, perhaps you’ve heard of Spirit Airlines flight NK2298, the August flight that outraged the Internet. Folks on social media looked at weather radar and the flight’s track and guessed that the aircraft had flown directly through Hurricane Erin, which was at a Category 4 status at the time.

Spirit Airlines responded to the concerns by informing the public that the pilots had followed standard procedure and flown around the weather. This aircraft was flying at 37,000 feet, and according to the available air and weather data, plus the lack of reports of severe injuries, the aircraft likely experienced no more than light turbulence. The aircraft was flying over the lower bands of the storm and successfully navigated around the hurricane.

Most pilots are not going to fly into a hurricane because there’s just no reason to. The safety culture of aviation places getting everyone home above all else, and a weather diversion is one reason why aircraft fly with more fuel than they actually need to complete a trip.

But note that I did say “most pilots” there. There are some pilots who do fly directly into hurricanes, and they are members of the awesome hurricane hunter crews that fly into the same storms that everyone else gets out of the way of. Without these planes and the crews in them, our understanding of hurricanes and their damaging forces would not be where it is today.

Into The Storm

The use of aircraft to study terrible weather dates back perhaps further than you’d think.

According to Weatherwise magazine (link downloads a PDF file), one of the first recorded attempts to track hurricanes with vehicles happened in 1932. As the magazine explains, in the early 1900s, weather forecasting suffered from a so-called “lost hurricane” problem. In 1906, Guglielmo Marconi invented the wireless telegraph, and it changed weather forecasting.

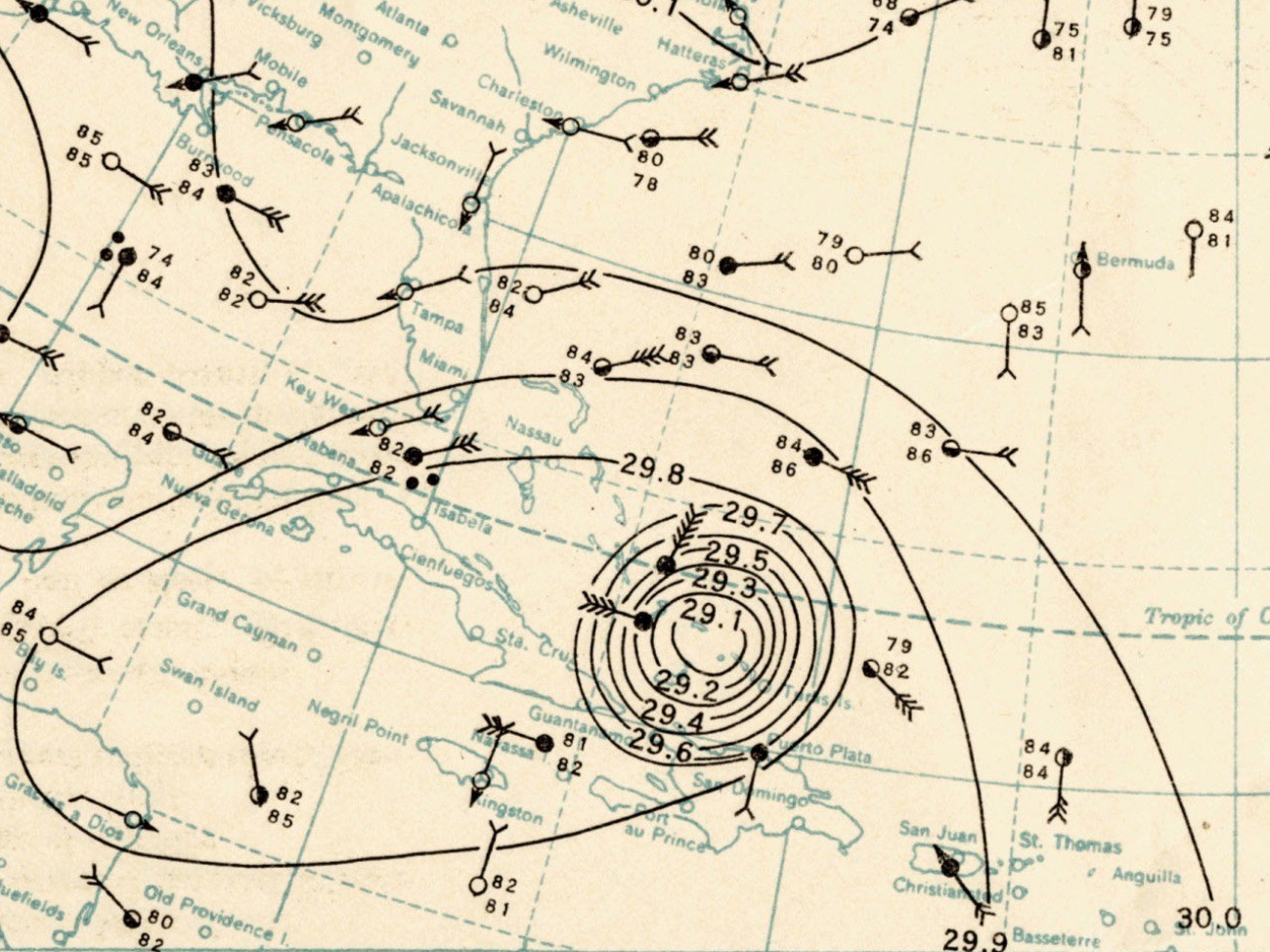

In the past, a ship had to make it to port to report on weather conditions at sea. This didn’t help the ships that were still at sea, and ships leaving port only had a rough idea of where the last ship had encountered a storm. However, with Marconi’s telegraph, ships could radio meteorologists about weather conditions. These meteorologists were then capable of charting a storm’s path based on those reports. Ships and meteorologists could then warn other ships about the storm, allowing them to steer clear and safe of the storm.

Unfortunately, this leap in weather forecasting technology had an unexpected consequence. Once the ships moved out of the way of the storm, the forecasters no longer had a way to track the storm, leading to a lost hurricane. Often, so many ships dodged hurricanes that meteorologists had no idea where storms were until they made landfall. By that time, it was too late to help people escape.

The late 1910s and 1920s are unfortunately filled with deadly hurricane disasters that could have had better outcomes if there were just some way to warn residents ahead of time. It would take one of these hurricanes to change the course of forecasting history.

In August 1932, Weatherwise writes, a hurricane slammed Galveston, Texas. Due to the lost hurricane problem, the residents got only four hours of warning. As the magazine writes, the city had been nearly destroyed by a hurricane in 1900 and had been hit several times after, and the city wanted to do something about it.

The Galveston Commerce Association set up a committee run by Captain W. L. Farnsworth that would find a way to solve the lost hurricane problem. The initial idea called for the cutter USCGC Saranac to sail into the Gulf of Mexico after hearing news of a hurricane. The ship would then ride through the storm, reporting its track, therefore allowing cities and towns time to evacuate. Understandably, the Coast Guard commander on base was not interested in sending his ship or crew directly into hurricanes.

Just two years later, the lost hurricane problem reared its ugly head again, when Galveston expected a hurricane, but the storm never came. People and authorities worried. Where did the storm go? Did it slow down? Did it turn? When the city reached out to the US Weather Bureau for clarity, they were told that the senior forecaster was unavailable as he was playing golf. Galveston ultimately dodged the storm, but residents were understandably upset.

Lost hurricanes would become an embarrassment for the Weather Bureau, and it would take drastic steps to improve the frequency of weather reports alongside the setting up of four dedicated hurricane warning centers.

Elsewhere in America, there was Joe Duckworth, then a Ford Tri-Motor pilot for Eastern Air Transport Service, the predecessor of Eastern Airlines. In August 1933, Duckworth was flying mail on a route from New York to New Orleans when he encountered a Category 1 hurricane moving through Washington, D.C. and the Chesapeake area. Once again, this was another lost hurricane that came almost without any warning. Duckworth, which had considerable experience flying only on instruments, managed to fly through the hurricane and into the eye of the storm, where he was able to spot his destination, Hoover Air Field. Duckworth would make his mail stop and take off again into the storm.

Hurricane Hunting

A decade later, a now Lt. Colonel Joe Duckworth would find himself flying into hurricanes once again. Weatherwise continues:

On July 27, 1943, Lt. Colonel Joe Duckworth of the US Army Air Forces (USAAF) was teaching instrument flight rules (IFR) flying to cadet pilots at Bryan Field, Texas, when word came down that all training flights had been canceled for the day. That morning, a hurricane had struck Galveston (150 miles southeast of Bryan) with little warning. Squally weather was expected in the area as the storm passed to the south. Anxious to test his IFR skills, Duckworth rounded up Lt. Ralph O’Hair as navigator, fueled up his AT-6 “Texan” trainer aircraft, and took off on a southerly course to intercept the storm. The pair encountered moderate turbulence but soon broke through into glorious sunshine with the Texas countryside visible below as they entered the hurricane’s eye.

They took a couple orbits inside the eye then turned around and landed back at Bryan Field. Lt. William JonesBurdick, the base meteorologist, had heard about the flight and demanded Duckworth take him up to see the storm. Duckworth complied, and Jones-Burdick scribbled down the first temperature observations made while flying into a hurricane. And without much notice or fanfare, that was it.

Weatherwise notes that there have been many urban legends told about this flight, but none of them actually happened. What you read above is it.

While this flight was novel, it wasn’t entirely unplanned. The first hurricane reconnaissance flight happened in 1935 during the infamous Great Labor Day Hurricane. Texans had been pitching the idea of storm patrols since the 1930s, and in 1936, Texas even filed a bill to use Coast Guard cutters to track storms. Others wanted to go even further and pitched the idea of using planes instead of boats. While ships would end up being used to track storms, the idea to use planes for that purpose died until it was revived during the outbreak of World War II. Suddenly, the Weather Bureau needed to track ships at sea, and the lost hurricane problem was still a thorn in its backside. The idea of flying planes to recon weather was back on the table.

In July 1943, the same month Lt. Colonel Duckworth had flown his flight, the Joint Hurricane Warning Center in Miami had begun sending aircraft to monitor tropical storms. So, while Lt. Colonel Duckworth might have been the first recorded pilot to fly through not one, but two hurricanes, monitoring storms using planes was already part of the plan before he even did it.

After World War II, the Air Force and Navy formed Hurricane Hunter squadrons to patrol the Atlantic and Air Force Typhoon Chasers and Navy Typhoon Trackers to cover the Pacific.

Since then, several aircraft types have been flown into hurricanes, including several repurposed Douglas and Boeing bombers, a Lockheed Constellation, variants of the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, and even a Lockheed U-2.

Today’s Hurricane Hunters

Flying into hurricanes is still a critical tool today. The National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) says:

Data collected by the agency’s high-flying meteorological stations help forecasters make accurate predictions during a hurricane and help hurricane researchers achieve a better understanding of storm processes, improving their forecast models.

Elsewhere, NOAA says:

The job of a hurricane hunter is not for the faint of heart. This brave crew must fly straight into one of the most destructive forces in nature. Hurricanes are born over the open ocean. And while satellites can track their movement, meteorologists and researchers need to sample the storms directly to get the most accurate information about them.

According to the Air & Space Forces Magazine, satellites are great for weather, but there are so many variables that they just cannot record. Having daring crews fly into storms with intricate equipment has increased the accuracy of weather models and hurricane track forecasts by 20 percent, which saves lives. The magazine continues that it costs at least $1 million to evacuate just a mile of coastline, so accurate reports don’t just keep people alive, but they also save money and time. Besides, if you were to evacuate the wrong place, there’s always the chance that evacuating traffic could clog up roads for a place that does need to evacuate.

Air & Space Forces Magazine continues by noting that forecast models still have a hard time predicting a storm that’s rapidly intensifying. So, if forecasters want the freshest, most accurate information, planes will be sent out. A major reason that the news about Hurricane Helene was so rapid was thanks to the work of the Hurricane Hunters of the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron. This crew is an Air Force Reserve unit stationed at Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi, and they flew nine missions into the hurricane between September 23 to 26, 2024.

NOAA’s hurricane hunting fleet consists of two Lockheed WP-3D Orion turboprops and one Gulfstream IV-SP jet. What’s fascinating about these aircraft is that, structurally, these planes are largely similar to their original designs. Yep, that means that these aircraft fly from as low as 500 feet to as high as 10,000 feet into storms with high winds and violent downdrafts just as they are, which is a testament to just how strong aircraft are.

Here’s what NOAA says about its WP-3D Orions:

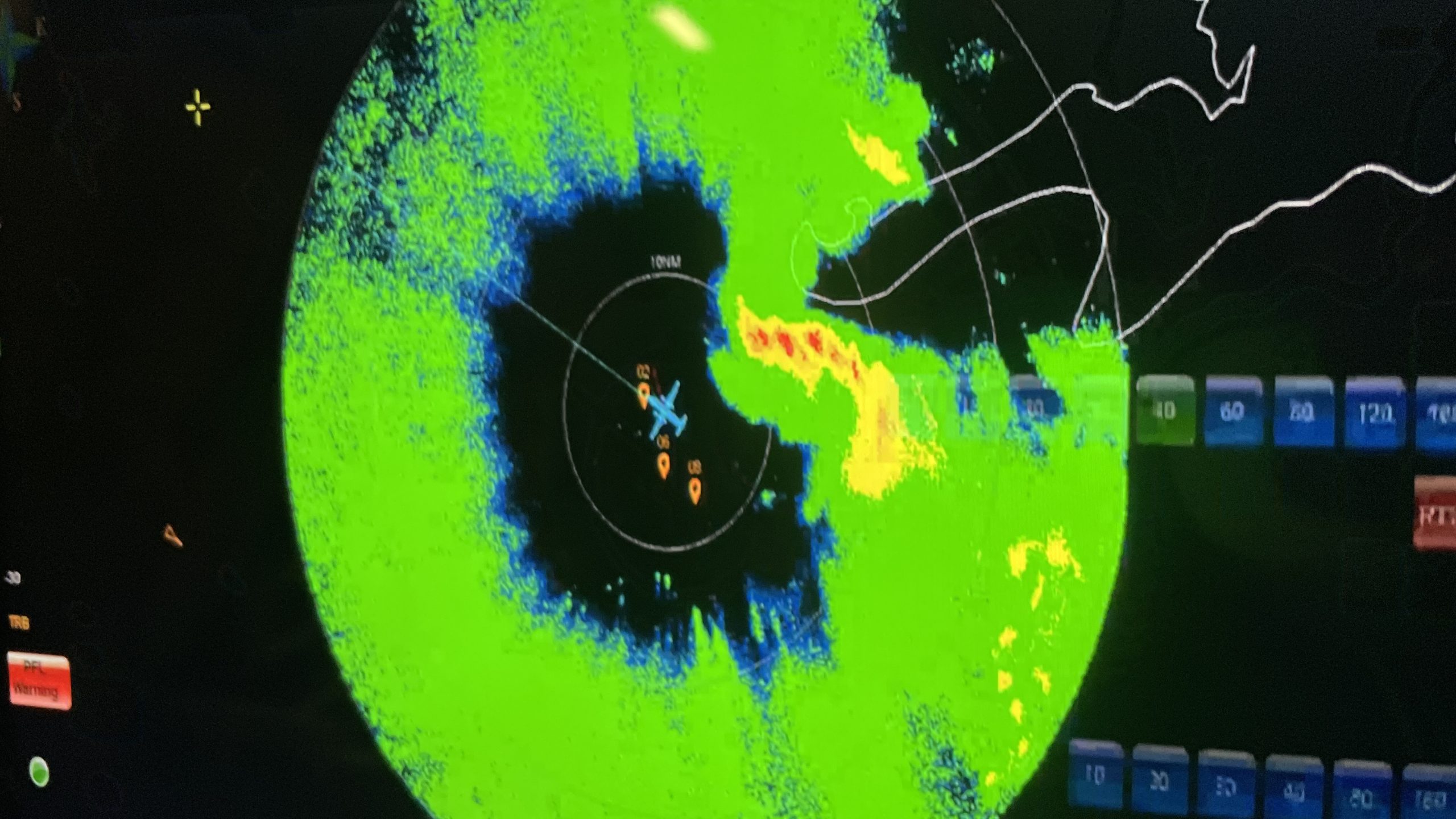

Scientists aboard the aircraft deploy Global Positioning System (GPS) dropwindsondes as NOAA Corps officers pilot and navigate the P-3 through the hurricane. These instruments continuously transmit measurements of pressure, humidity, temperature, and wind direction and speed as they fall toward the sea, providing a detailed look at the structure of the storm and its intensity. The P-3s’ tail Doppler radar and lower fuselage radar systems, meanwhile, scan the storm vertically and horizontally, giving scientists and forecasters a real-time look at the storm. The P-3s can also deploy probes called bathythermographs that measure the temperature of the sea.

Storm surge forecasts have benefited from the addition of NOAA-developed Stepped Frequency Microwave Radiometers (SFMRs) to NOAA’s P-3s. SFMRs measure over-ocean wind speed and rain rate in hurricanes and tropical storms, key indicators of potentially deadly storm surges. Surge is a major cause of hurricane-related deaths.

In addition to conducting research to help scientists better understand hurricanes and other kinds of tropical cyclones, NOAA’s P-3s participate in storm reconnaissance missions when tasked to do so by the NOAA National Weather Service’s National Hurricane Center. The purpose of these missions is primarily to locate the center of the storm and measure central pressure and surface winds around the eye. (The U.S. Air Force Reserve’s 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron also supports this mission with their WC-130J aircraft.) Information from both research and reconnaissance flights directly contribute to the safety of people living along and visiting the vulnerable Atlantic and Gulf coasts.

The Gulfstream IV-SP is also pretty awesome:

NOAA’s Gulfstream IV-SP (G-IV) which can fly high, fast and far with a range of 4,000 nautical miles and a cruising altitude of 45,000 ft., paints a detailed picture of weather systems in the upper atmosphere surrounding developing hurricanes. The G-IV’s data also supplement the critical low altitude research data that are collected by NOAA’s P-3s.

Since 1997, the G-IV has flown missions around nearly every Atlantic-based hurricane that has posed a potential threat to the United States. The jet’s mission covers thousands of square miles surrounding the hurricane, gathering vital high-altitude data with GPS dropwindsondes and tail Doppler radar that enables forecasters to map the steering currents that influence the movement of hurricanes.

NOAA has also used the G-IV to gather important data upstream of winter storms and study “atmospheric rivers,” narrow bands of moisture that regularly form above the Pacific Ocean and flow towards North America’s west coast, drenching it in rain and packing it with snow.

It’s noted that the Gulfstream only gathers data around storms. NOAA doesn’t send this jet through the eye.

These aren’t the only aircraft used to hunt hurricanes. The 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron flies a fleet of 10 Lockheed WC-130Js. These aircraft, like the Gulfstream and the WP-3D Orions, also wear their standard structure. The squadron says that the primary differences between the WC-130J and a standard C-130J Hercules are the additions of two external fuel tanks and palletized meteorological data-gathering instruments. These are planes that weren’t built specifically to fly through hurricanes, yet they have worked really well for the task.

Flying Into A Storm

As for how these missions are flown, as CNN writes, the 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron will often fly a pattern that looks like the Alpha symbol (α) in the Greek alphabet. In most missions, Hurricane Hunters fly what’s known as the Alpha Pattern, which involves flying into the storm at a “corner,” and then the flight will collect data from four corners. These missions mark the center of a storm’s circulation, monitor pressure changes and wind speeds, and gather other raw data.

Other patterns include an ‘X’ pattern, a ‘Z’ pattern, and a box pattern. If these aircraft are being sent into storms that are toward the beginning of their lifecycles, the airplane crews may fly a more flexible pattern as they determine if a system meets the definition of a tropical cyclone.

On the other hand, NOAA flies several patterns, including ones that look like stars, rows of crops, plus signs, and stars. The NOAA Gulfstream could be seen flying a star pattern where it gets right on the edge of a storm, but not through its roughest parts. As for what all of this is like from the perspective of the crew, NOAA tells that story, too:

Dr. Chris Landsea presently at NHC writes of his experience flying research missions into hurricanes, “The most incredible sight that I’ve ever seen is in the middle of a strong hurricane. One might not believe this, but most hurricane flights are fairly boring. They last 10 hours, there are clouds above you and clouds below – so all you see is gray, and you don’t feel the winds swirling around the hurricane.

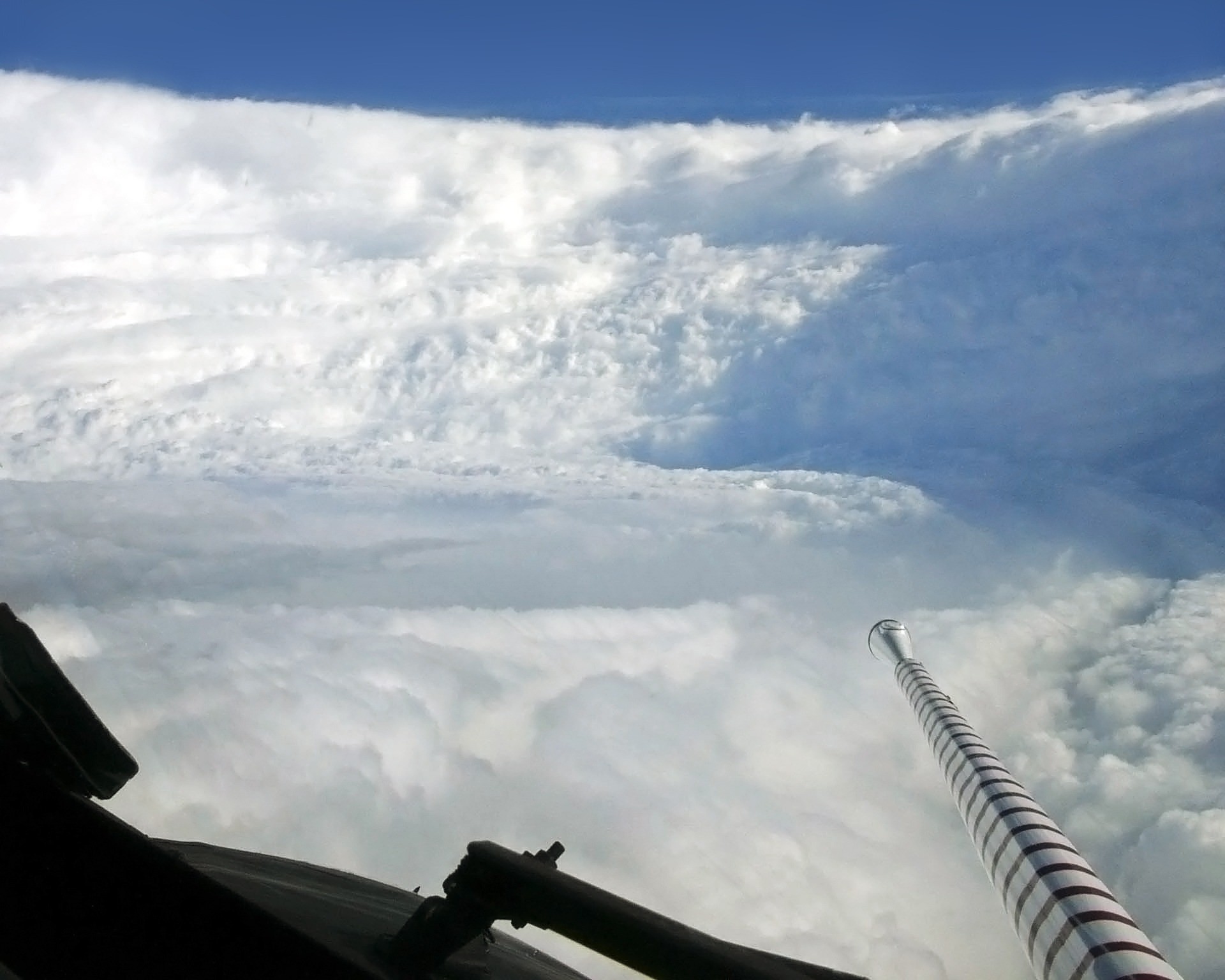

But what does get interesting is flying through the hurricane’s rainbands and the eyewall, which can get a bit turbulent. The eyewall is a donut-like ring of thunderstorms that surround the calm eye. The winds within the eyewall can reach as much as 200 mph [325 km/hr] at the flight level, but you can’t feel these aboard the plane. But what makes flying through the eyewall exhilarating and at times somewhat scary, are the turbulent updrafts and downdrafts that one hits. Those flying in the plane definitely feel these wind currents (they sometimes makes us reach for the air-sickness bags). These vertical winds may reach up to 50 mph [80 km/hr] either up or down, but are actually much weaker in general than what one would encounter flying through a continental supercell thunderstorm. But once the plane gets into the calm eye of a hurricane like Andrew or Gilbert, it is a place of powerful beauty: sunshine streams into the windows of the plane from a perfect circle of blue sky directly above the plane, surrounding the plane on all sides is the blackness of the eyewall’s thunderstorms.

Directly below the plane peeking through the low clouds one can see the violent ocean with waves sometimes 60 feet high [20 m] crashing into one another. The partial vacuum of the hurricane’s eye (where one tenth of the atmosphere is gone) is like nothing else on earth. I would much rather experience a hurricane this way – from the safety of a plane – than being on the ground and having the hurricane’s full fury hit without protection.”

In another article, NOAA Hurricane Hunters Flight Director Richard Henning describes the experience as being like riding a rollercoaster in a car wash. What a visual.

Weather Heroes

Thousands of missions have been successfully flown since the creation of the program, and the vast majority of the time, they complete without any issue. Sadly, in decades past, there were some brutal tragedies. Six weather recon aircraft have been lost between 1945 and 1974, resulting in the deaths of 53 crew. While there have been damaged aircraft in the decades since, the planes have always gotten home.

It might be hard to picture intentionally flying an aircraft into a strong storm. After all, you’ve probably been on a flight where you had to deal with some turbulence in clear air, let alone a hurricane. Yet, these flights are crazy, but not as death-defying as you might think.

These flights also serve a vital role in weather forecasts, as these planes reach places that satellites and other tech cannot. So, the next time you see a big storm on the map, check a flight radar app. You might just find a crew of some of the coolest pilots and scientists on the planet flying a plane around a storm to keep as many people safe as they can.

Top graphic images: NOAA; depositphotos.com

“they were told that the senior forecaster was unavailable as he was playing golf.”

Ted Cruz? Ha ha

I’ve been to the Air and Space Museum, there’s really nothing there

(I’ll see myself out…)

Another great article!

I just hope that anyone who tries to DOGE these flights, and all the people analyzing the data they gather, lives near a coast and gets to see first-hand what happens when you try to cut these budgets.

Exceptional article Mercedes! If there were awards for auto journalist articles, this would be tough to beat. Great history, pictures, and current relevance.

This rocked!

“Rock you…like a hurricane!”

My best friend’s dad flew Connies for the Navy with VW-4 in the early 60’s. He does that downplaying thing when pressed about it, but with just enough horrifying details to make you feel like you’d need to call a Code Brown in a real hunt.

Yeah science!!!!!!

6 years in the Navy, 4 on an aircraft carrier, and we dealt with two hurricanes if I remember correctly. Being in the engine room at 3am, me on one side, another guy on the other side. We made a ball out of a bunch of tape, and would let the ship rocking back n forth roll it across the deck.

Things you do on watch at 3am. I never got seasick from it at least.

Hopefully these folks didn’t get Doge’d right before hurricane season…

NOAA is taking a hit. Orange guy is mad that his Sharpie maps got ridiculed

Support NOAA by letting your US Senators and Congresspersons, particularly Republican congresspersons, know how important NOAA funding is to you.

My dad flew P3s for the Navy to hunt for subs and was deservedly proud his airframe is still in service on hurricane duty. He said the great thing of the P3 is that it was slow and could hang on station forever. He also said it was almost impossible to kill and they’d fly in any weather without much worry.

Also called a Heisencane.

This is a fantastic article, Mercedes. Thanks for sharing this knowledge with us and for highlighting some of the good work our government does for its citizens! The Internet will get no better today.

Dr. Jeff Masters has an absolutely engrossing article on flying through Hurricane Hugo when it was already a cat 5. Good example of both how tough the P3 and its crew are and the forces that a hurricane can generate.

For a more historical perspective, the Typhoon Cobra fiasco shows just how important it is to get timely and accurate tracking information. Due to a combination of delayed and incomplete information and lack of familiarity with maritime best practices Task Force 38 sailed directly through cat 5 typhoon with catastrophic results. The Unauthorized History of the Pacific War Podcast has a good episode on what happened.

Edit: huh, links got stripped. Guess you’ll just have to google.

ty for this. I know a ton about the pacific war but never knew about this!

I picked up a book about that (“Halsey’s Typhoon”) at a library book sale this summer. Haven’t started in on it yet.

Ooo thanks for the recommendation. Looks like my local library has it, I’ll check it out. Be interesting to get another perspective on what happened.

Thanks for the recommendation- absolutely engrossing read. The USS Tabberer, her captain and crew are fully deserving of every honor possible. It’s interesting in the divergence of opinion on Halsey between this author and the Unauthorized History of the Pacific War Podcast. That said, given my naval engineering background I’m firmly of the idea that the sea is trying to kill you and should take priority.

On a side note, the thought of being on a ship taking 70+ degree rolls is absolutely terrifying. I am very glad that I’ve only encountered typhoons/hurricanes while being safely ashore and in stoutly constructed buildings.

Wow, this is awesome! I was sort of vaguely aware of these planes, but this is so much cooler than I expected. I never would have thought about the updrafts and downdrafts being more intense for flying than the winds, and it really shows how skilled these pilots have to be.

Those Orions are basically an updated version of the L188 Electra airliner from 1957, fantastic plane, durable and pretty frugal on the fuel

I am so impressed and love that this is both badass and good science. I hope they all continue to get funding, keep their jobs, and are listened to.

It’s incredible that none of these aircraft have crashed since the 70’s!