Electric pickup trucks have long found themselves in a bit of a weird place. Trucks like the Ford F-150 Lightning and the Rivian R1T have the guts and power to do some impressive hauling, but their short range means they’re impractical for all but the most local towing jobs. The Chevrolet Silverado EV is the antidote, being the first electric pickup with legs long enough for drivers to dare to tow long distances on electric power. The towing range is impressive in itself, but that range is also wrapped in a package so good at hauling that you might not want to buy a diesel. But there’s a catch, I think, and it’s that America just isn’t ready for people to tow long distances with electric trucks yet.

I had the privilege of testing a 2026 Chevrolet Silverado EV Trail Boss for a little longer than the duration of the 2025 EAA AirVenture Oshkosh aviation spectacular. I used this beast of a truck to tow a 7,746-pound, 36 feet, 9 inch long travel trailer approximately 133 miles in each direction. Then, I used the truck to get around Oshkosh, including brief stints going mudding in the fields around camp.

The Silverado was shockingly good at towing a trailer and had enough towing range that so-called “range anxiety” just wasn’t a thing for me. However, I had plenty of anxiety for another reason during this trip, and it was over charging stations. It wasn’t the availability of chargers, as there were plenty, but how they were designed without considering the future.

(Full Disclosure: General Motors loaned me a Chevrolet Silverado EV Trail Boss for a little over a week to do a road trip with. I received the truck with a 96 percent charge and paid for my own juicy recharges.)

The State Of Electric Hauling

First, I want to explain the state of electric pickup trucks and hauling. On July 30, I explained that when you’re towing a trailer, regardless of whether your tow rig is gas or electric, aerodynamics usually matter more than weight. Car publications and YouTubers love to talk about how they towed 6,000 pounds or 11,000 pounds with their electric pickup trucks. While these weights are impressive, they do not tell the whole story.

As Robert Dunn of Aging Wheels had proved with his independent testing, weight isn’t nearly as important as many people would think. A 1,500-pound trailer with a 12-foot-tall wall on its front will almost certainly result in your truck guzzling more battery or more gas than that same truck towing a 6,000-pound trailer that’s completely flat. Likewise, if you parked a car behind the giant wall of that first trailer, your fuel economy or range is unlikely to get much worse because the heavier hit wasn’t weight, but trying to ram something the shape of a brick through wind.

This is also why some of the most fuel-efficient cars on the planet practically slice through air. While weight absolutely has a huge importance in towing, from whether your vehicle’s structure can support the trailer to stopping distance, climbing performance, and more, aero and frictional drag are your main enemies for efficiency. If you don’t believe me, watch this:

This applies to my towing situation. It sounds impressive that I got the Silverado EV Trail Boss to tow a 7,746-pound, 36 feet, 9 inch long travel trailer so many miles on a single charge, but the real impressive part is that, as you can see with your own eyes, this trailer’s front wall towered over the Silverado EV and dragged it down in wind.

These findings are reflected in real-world towing testing. Back in 2022, Car and Driver made a Ford F-150 Lightning, a GMC Hummer EV, and a Rivian R1T tow the same 6,100-pound, 29-foot camper. The Ford had only 100 miles of towing range, or less than half of the 230 miles of highway range that it had when unloaded. The Rivian scored only slightly better with 110 miles of towing range against its 280 miles of highway range. The winner of the test was the GMC Hummer EV, which went only 140 miles against the 290 miles that it could do at the same speed while empty.

How about the Tesla Cybertruck? The Fast Lane Truck hitched a 7,500-pound camper and averaged 1.1 miles per kWh, which is actually pretty good efficiency while towing. However, even with that efficiency, it still would have resulted in a theoretical towing range of just 135 miles, and that’s driving the truck until it’s dead.

Honestly, this kind of towing range is pathetic for someone like me, who often tows big trailers over large distances. Stopping just over every 100 miles to charge for 30 minutes or longer would make any road trip a total drag. Certainly, it would be impossible for me to pick up a car from the Port of Baltimore and then drive the 773 miles back home on the same day.

This was pretty much the state of towing with an electric pickup truck for a while. All of these trucks are actually really good at towing, and their all-electric powertrains make pulling thousands of pounds feel like child’s play. But range and charging limitations mean that these trucks can never live to their full towing potential.

That was until the Chevrolet Silverado EV arrived on the market in the 2024 model year. It sounds like a cliche, but this truck changed the electric towing game.

Big Weight, Big Power, And Big Range

This was demonstrated in real life as both car publications and YouTubers started putting up towing range figures large enough to make you do a double-take. The guys of The Fast Lane Truck hitched a 6,000-pound enclosed cargo trailer to a Silverado EV and managed to get 230 miles of range out of the truck. Zack of JerryRigEverything hooked 11,000 pounds of trailer and Humvee up to a Silverado EV and got 177 miles of range – not bad. Robert Dunn from earlier has been using his Silverado EV like any truck owner would, taking it on long-distance trips and making it work just as hard as a gas truck.

I just got to experience the Silverado EV myself, and my experience mirrors theirs. But why? How does the Silverado EV manage to do what other electric pickup trucks have not?

The Silverado EV was announced during the 2022 Consumer Electronics Show, and what General Motors built out of the other end is something different. The Silverado EV is not just the Silverado with electric power. Instead, GM placed the Silverado on its Ultium BEV platform, utilizing a unibody with an integrated bed and integrated frame rails. General Motors says that the Silverado EV has a similar wheelbase and dimensions to a gas-powered Silverado, but they are technically unrelated.

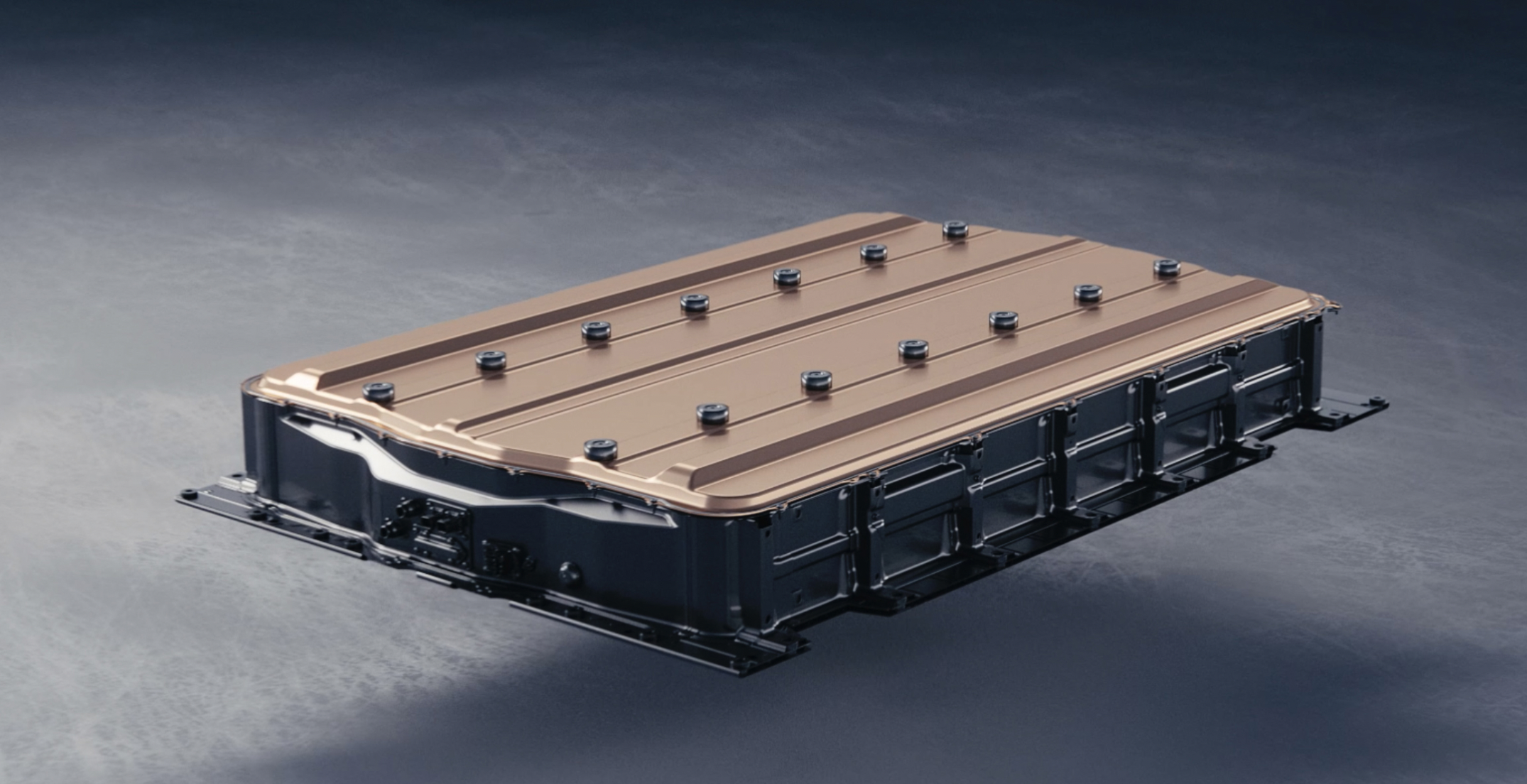

The secret sauce to the Silverado EV’s towing range actually isn’t all that special. In building its electric trucks, General Motors just layers on a silly amount of batteries. Unfortunately, that’s just the reality with today’s battery technology. If you want to tow a huge trailer really far, you need to get the aero as good as you can get, and then pile on the batteries. In GM’s case, the Silverado EV technically has an 800V architecture, but how this works is that GM has a dual-layer 400V battery, and the 800V and 350 kW are split between the layers.

The downside of this is that GM’s electric trucks are crazy heavy. The Silverado EV 4WT weighs 8,568 pounds, while the Silverado RST is a staggering 8,953 pounds. The Trail Boss lands at a bit over 8,500 pounds. For those of you keeping count, this makes the electric about twice as heavy as an ICE half-ton truck. The Silverado is even about 2,000 pounds heavier than a Tesla Cybertruck.

A Silverado EV’s Max Range battery pack weighs 2,900 pounds all on its own. Of course, all of these batteries mean that electric trucks get expensive. Autopian contributor Sam Abuelsamid has noted that, with current technologies, batteries cost about $100 to $150 per kWh, and GM’s trucks have more than a ton of batteries, literally. I’ll get back to the cost later.

Building EVs can put a manufacturer into a vicious cycle. One of the best ways to gain range is through putting in more batteries, but more batteries mean more weight, more cost, and worse performance. Having a titanic brick of a truck that’s filled with heavy batteries is also terrible for efficiency. As a result, the Silverado EV might have the best range of its competition, but it also has pretty awful efficiency of 2.0 mi/kWh when unloaded and sometimes well under 1 mi/kWh when towing.

However, at least for General Motors, making its electric trucks hilariously heavy and filled with batteries is necessary because, at least in GM’s eyes, electric trucks need to be able to tow a trailer a decent distance. So here we are.

The big question is, what does all of the above mean in the real world?

Like A Rebirth Of The Avalanche

GM loaned me a 2026 Silverado EV Trail Boss with the 205 kWh Max Range battery for a claimed range of 478 miles and manufacturer-rated efficiency of 2.0 miles per kWh. Power comes from dual motors punching out a total of 725 HP and a whopping 775 lb-ft of torque. All of this is good for a 60 mph acceleration time just a tick over four seconds, which is nutty for something weighing as much as a condo.

I first got to experience the Silverado EV how most people will, and that’s by driving it around unloaded. Visually, the Silverado EV looks like a futuristic Chevy Avalanche, but with more streamlining and without the huge grille that the trucks of today have. The Avalanche part is most apparent in the integrated bed, the sail pillars above the bed, and, of course, the Silverado EV’s handy midgate, which I will get back to in a moment.One neat note about the truck’s design is that, due to not needing to house a V8 engine, the hood isn’t as massive as it would be on a gas truck. Likewise, the area under the hood serves as a frunk that’s large enough to swallow a whole suitcase. The frunk can also function as a cool bench to sit on while tailgating. See?

It all adds up to the Silverado EV being an inoffensive truck that’s easily ignored in the sea of vehicles on the road. The only people who stared at the Silverado were existing EV owners. Everyone else just went about their day. If you’re the kind of person who doesn’t want to talk breathlessly about your car every time you stop, the Silverado EV will be great at helping you blend in – assuming there aren’t any EV aficionados waiting to jump out of the bushes.

Hopping into the truck further reminds you that this is no regular half-ton truck. The interior features a pair of giant screens, and the design feels more like the minimalist futurism that EV interiors are known for rather than the sort of muscular and blocky interiors that ICE pickup trucks go for. Trucks like the Tundra have giant knobs with fake exposed fasteners on them, while the interior of a Ford tries to remind you that you’re in a hard-wearing working vehicle. The Silverado EV’s interior feels like one that could have come out of any generic crossover.

The quality of this interior is not exactly as I expected for a truck that’s nearly $100,000. The dashboard was covered in a synthetic textured material that looked pretty cool and felt pretty okay to the touch, but seemed out of place in this price bracket. This was the kind of material that I’d expect to see in a $30,000 crossover.

The Trail Boss makes up for it with cushy leather seats with heating and ventilation. I also enjoyed how the truck had physical buttons for common HVAC functions; however, I do feel that the button placement was inefficient. Do we really need two separate buttons for fan speed? You could have one toggle switch for fan speed and then use the other button to toggle between blend modes.

Ergonomics in the truck were pretty good, and I found that, like you’d get in a typical ICE truck, there was more than enough headroom to wear a cowboy hat while driving. My wife said that the Silverado EV had her favorite truck interior yet, and part of that was due to the fact that it didn’t really have a typical truck interior. It felt more like a car in there than a truck.

Around Town

The driving experience of the Silverado EV Trail Boss was a bit unlike any other truck I had driven, and not just because it’s electric.

The electric part of the driving experience was nothing particularly special. Like all EVs, the Silverado EV leaps off the line with a stupid amount of power, and it accelerates way faster than you’d expect 9,000 pounds of truck to go. The Silverado EV is so fast that it can outrun legitimate sports cars in a straight line. The Silverado EV also makes driving fast so easy that it can be dangerous for pedestrians and other drivers if you aren’t careful. But again, none of this is particularly surprising as pretty much all EVs are crazy quick nowadays.

I also wasn’t at all surprised to find that this huge heap of truck didn’t have particularly great handling. Throw the truck into a corner, and the body will want to continue in the direction you just departed from before being forced to turn by the tires, which then scream in pain because you fancy yourself as a racing driver while commanding something weighing as much as a small cruise ship. Though quick in a straight line, the Silverado understandably does not like to be hustled through turns. Otherwise, handling is safe and predictable, and the truck’s suite of stability control and traction control aids will try to keep you from having too much fun. Don’t expect to take your Silverado EV on any track days.

The Trail Boss features an independent coil suspension with a factory lift and a hydraulic rebound control system. In addition to the high-riding suspension, the Trail Boss has 18-inch wheels, 35-inch all-terrain tires, meaty tow hooks, and a special off-roading mode. This is compared to the air suspension that you get in the regular Silverado EV. The Silverado EV weighs as much as a heavy-duty pickup truck, but it has the ride of something like a half-ton Ram. The suspension soaks up bumps well enough that you should feel pretty comfortable, even on long trips.

The Trail Boss made for an excellent daily driver. It’s supremely quiet, even with the faint rumble of all-terrain tires in the background. The truck has a plethora of cameras to help you fit into tight spaces, rear-wheel-steering that genuinely makes the truck feel a little bit smaller when you’re maneuvering, and the Android Automotive operating system in the infotainment screen didn’t take very long to get used to.

Quirks

Sadly, I do have one major complaint about this interior, and it’s about quality. One of the speaker grilles wasn’t fully installed. This truck had just 300 miles on it when I got it, and somehow, nobody noticed this? Some heavy percussive maintenance with my fist locked the speaker grille in place, and it did not come back up again for the rest of the trip.

One of the trim panels attached to the steering wheel was also not fully installed. This one had no fix. Every time I snapped it into place, it popped right back out again.

This truck also had dashboard stitching to match the seats. It was a nice visual touch, but the stitches were more or less fake since they weren’t joining any seams together, and some segments of stitching weren’t straight. This was the same observation Sam made in his Silverado EV tester back in 2024.

The stereo in my truck was a Bose 7-speaker unit, and it was fine. It wasn’t nearly as crisp or as rich as Ford’s Bang & Olufsen system or the Harman Kardon systems in Ram trucks, but the Bose system did deliver healthy bass and remained clear even at the high volume levels that I play my music at. You aren’t likely to impress anyone with this system, and you don’t really get a surround-sound feel, but you can have a more than satisfying sonic experience in this truck. Mercedes Jam Session Approved!

About The Midgate

The midgate also brought an interesting quirk. I carried four gas cans along for this trip to fuel my generator. When I carry gas cans, I always secure the cans to a tie-down in the bed so they aren’t just sliding around. This works flawlessly almost every time. In the past, if a gas can went rogue and broke loose, it was no big deal – mop up the gas spill, wash the bed, and keep on truckin’.

On one gas station visit, my dad helped me fill the cans, but he skipped the tie-down step. Later, as I was driving the Silverado EV around Oshkosh, I started smelling gas. Wait, I’m in an EV, why does it smell like gas? As you have probably guessed, one of the gas cans had turned over and was leaking fuel, the fumes of which leaked through the midgate’s seals. The tonneau cover was open, unlike in the photo above, but that didn’t matter. I cleaned up the spilled gas, washed the truck bed, and washed the midgate, but the smell of gas lingered inside the truck for about a day.

During the drive home, I had the generator in the bed and under the now-closed tonneau cover. I had drained the gas out of it, and the gas cans were now in a different truck, so I figured that wasn’t going to be a big deal. Yet, the interior of the Silverado began smelling like a hardware store, or basically what my generator smells like.

I don’t know if my truck had an issue or if that’s just how the midgate is, but definitely be careful. If you’re carrying a load that emits a foul odor or has fumes, keep the tonneau cover open and try to prevent spills.

The Big Haul

The Silveradio EV is made to haul, not for puttering around town. What we’re really here for is towing, and I did plenty of that. I started off my trip to Oshkosh by topping off the truck’s battery. I had taken the truck to the beach and around town, consuming about 25 percent of the battery to drive 100 miles. Keep in mind that I was having lots of fun with the truck’s Wide Open Watts (WOW) Mode, which unlocks the truck’s maximum acceleration potential. I went to a local Thornton’s gas station, which had a 150 kW charger that topped me up to 100 percent in about 40 minutes or so while I wrenched on my generator’s carburetor.

With a totally full battery, I drove over to my parents’ place to pick them up, and then I drove to where they had their trailer stored. The total distance here was about 20 miles, and I averaged about 2.4 mi/kWh, arriving at the storage facility with 95 percent battery.

Hitching up the trailer went no differently than the hitching process with a gasoline truck, and then it was time to hit the road. Earlier, I mentioned the 2022 Heartland Mallard M33 has a dry weight of 7,746 pounds and measures 36 feet, 9 inches long. However, quoted dry weights are never truly accurate, especially after you factor in options, propane, and water. In my case, the actual weight was likely closer to 8,000 pounds.

This is important because while the Silverado EV has a max towing capacity of 12,500 pounds and a max payload of 1,800 pounds, that figure is only for the low-end work truck models. The Trail Boss, like other higher models, has a towing capacity of 10,000 pounds and a payload of 1,500 pounds. In other words, the family camper used up about 80 percent of the truck’s capacity.

Yet, the truck didn’t seem to care. The Silverado EV is so powerful that it accelerates fast even when towing a heavy trailer. It pulls from a dead stop so fast that, if you have a poorly built camper, you can probably cause damage to it just by yanking it so hard with the Silverado EV. This truck accelerates as hard, if not harder, than a diesel truck, but without shifting, diesel exhaust fluid, particulate filters, diesel fuel, or anything like that.

Once you hit cruising speed, the diesel-like performance continues, as the Silverado has a groundswell of power in store for passing and climbing hills. Add in great stability, the quiet interior, and GM Super Cruise, and the truck makes towing a huge trailer feel basically effortless. Just point the truck down the road, and it’ll pull you and the trailer along for the ride without breaking a sweat.

I even love how the truck uses a combination of regeneration and friction brakes to pull the whole rig to a stop in a manner that feels more confident than an ICE truck. I can’t believe I’m saying this, but I’d rather tow a big trailer with an EV than with a diesel truck. Look, I know, I’m the Autopian’s resident diesel freak. But it’s hard to deny just how great the Silverado EV is a handling trailers.

But here’s where my compliments turn to concern.

Bizarre Problems

The first problem I had was with Super Cruise. The system worked great about 95 percent of the time. It was alarming how freakishly good the robot was at towing a trailer. We stayed perfectly between the lines, kept a consistent pace, and the truck was a safe driver, keeping a good distance away from traffic in case of an emergency. The only feature that didn’t work while towing was Super Cruise’s automatic lane change function, but the truck had no problem taking back over once you helped it do a lane change.

What concerned me was the other five percent of the time. There were times when, seemingly out of nowhere, the truck would begin to accelerate by itself. I chose a cruising speed of 65 mph for much of my trip, and when the truck started accelerating by itself, I often saw it creep to 75 mph, 80 mph, or even 85 mph on the cruise control display.

On the other hand, the truck sometimes slammed on its brakes for no apparent reason. Not full panic-braking force, but definitely something akin to the hard braking you might apply when a car in front of you suddenly jumps on the binders and you find yourself too rapidly closing distance. When these braking incidences occured, there wasn’t any traffic in the truck’s way, or a construction zone, or anything like that – but the truck would brake hard, and I’d look down and see that Super Cruise set itself to 45 mph or 50 mph.

Now, it would be easy to say that maybe I flicked the speed switch without realizing it, but here’s the thing: Super Cruise is a hands-off driver assist system. I can’t adjust the speed if I’m not touching the steering wheel, which I wasn’t.

My best guess is that the truck was misreading speed limit signs. There was one occurence when I was able to watch this happen in real time. I had the speed set to 65 mph, and upon passing a 70 mph sign, the truck changed the setting to 75 mph and began accelerating. The speed limit where I was driving on I-94 and I-41 in Wisconsin never exceeds 70 mph, so the truck had no reason to be selecting speeds as high as 85 mph.

I considered dirty camera lenses as a culprit for misread signs (if mis-read signs were indeed the problem), but the truck was clean. Sadly, in my time since having the truck, I’ve gotten no closer to getting a clear answer as to what Super Cruise was doing.

The other part of that 5 percent includes a time when Super Cruise pulled a right turn at 65 mph, which would have driven the truck off of the highway had I not been paying attention, and another time when Super Cruise attempted to drive into the shoulder after a semi-truck passed us on the left. This happened enough times that my mom and I started joking about how the robot is afraid of semi-trucks.

While these events were infrequent enough that I continued to use Super Cruise, I think they’re worth mentioning because they can be critical safety issues if you don’t take over the second the truck makes the mistake.

The Charging Pickle

When I wasn’t babysitting Super Cruise, I also found myself in another pickle. The Silverado EV Trail Boss averaged 2.1 miles per kWh when I was driving it empty on the highway. With the trailer, I got between 0.7 mi/kWh and 0.9 mi/kWh. This truck was absolutely guzzling down its battery.

Now, because the battery had 205 kWh of usable juice, that still results in decent range. A rating of 0.9 mi/kWh results in a theoretical range of 184.5 miles, which is pretty awesome considering the circumstances. However, the times I averaged 0.7 mi/kWh concerned me because that’s a theoretical range of 143.5 miles. The drive from the camper’s storage spot to Oshkosh was 133 miles, so you can see my concern there.

Weirdly, this wasn’t range anxiety, at least, not in the traditional sense. There were tons of fast chargers all over my route. The problem is that pull-through charger infrastructure is currently nonexistent in many parts of America. Yes, truck stop chains, General Motors, and others are working to build trailer-friendly EV chargers, but they just don’t exist yet in many regions, and one of those regions includes massive swaths of Wisconsin. There wasn’t a single pull-through charging station along my route.

If I had to stop to charge, I really had only three choices. I could either charge with the trailer hooked up, and block 40 feet of a parking lot, I could detach the trailer and the weight distribution hitch springs, charge, and then hook back up, or I could find one of those Tesla stations with a solitary stall that’s compatible with EVs towing trailers, and hope that whoever designed the lot didn’t put that charger next to the parking lot entrance.

That’s it. Those were my three choices, and they all sucked. Making matters worse was that, as I discovered, there are a lot of chargers that are listed on apps like PlugShare as being fast, but when you plug in, you get a charging rate that’s barely better than Level II.

Oh, and there’s one more curveball, too, because my Silverado EV tester could not accurately estimate remaining range when it was towing. When I hitched up the trailer and turned on tow mode, the truck told me that I would reach my destination with 51 percent charge remaining. I knew that was a load of nonsense. I assumed the truck would average about 1 mile per kWh while towing, which would mean spending at least 133 kWh of the pack to drive the 133 miles that I needed to drive. Now, I’m not a mathematician, but that’s more than 51 percent.

I figured that the estimated range would correct itself as I pulled the trailer. The problem was that while the range estimation slowly counted down, saying that I’d arrive with maybe 45 percent battery or maybe 35 percent battery, the estimation was always very optimistic. If I could suggest an improvement, it would be that the range estimator should be able to pull data from the truck’s efficiency monitor. The truck knew it was averaging 0.9 mi/kWh, but the estimator apparently didn’t get the memo.

Instead, I calculated range by hand. I set the truck to a constant 65 mph, and during the trip to Oshkosh, I maintained a consistent 0.9 mi/kWh. Based on my hand calculations, I’d make it without issue so long as my efficiency didn’t drop. I ended up ignoring the range estimator for the entire trip, which was annoying, because I was basically betting on my math being correct.

Thankfully, I arrived at camp with a 24 percent remaining charge after consuming 71 percent of the battery. I then let the truck sit overnight without charging it, and by the next morning, the truck actually read 28 percent charge. Neat!

The drive home was much more challenging, as the temperature was above 90 degrees and there was a wicked crosswind. On that trip, the truck averaged 0.7 miles per kWh for about a third of the drive. That 0.7 mi/kWh even included having to slow down to between 55 mph and 60 mph due to traffic. Things got much better in Milwaukee, and I was able to increase speed back to 65 mph to 70 mph while efficiency rose to 0.9 mi/kWh. That time, I arrived home with 22 percent charge after consuming 70 percent of the battery, which included air-conditioning, which used a little over 2 kWh of juice.

When it did come time to charge, I was impressed with the charging performance of the Silverado EV. Assuming that you can find a properly-equipped charger, the Silverado EV can suck up to 350 kW of juice. The fastest charger I found in Oshkosh put out 178 kW. I plugged in with 8 percent remaining, and after about an hour and a half, the truck’s battery was back to 100 percent.

GM provided me with an NACS adaptor, which meant that I gained access to Tesla Superchargers. These had a knack for starting out at around 178 kW, but then quickly throttling down to 60 kW before recovering back to 70 kW. This is a common issue with charging GM EV trucks on the Tesla Supercharger network, and means that if you have the choice, go somewhere else to top up. Otherwise, don’t be surprised if it takes a couple of hours to get enough range to start towing your trailer again.

In terms of charging costs, running the Silverado EV cost me about as much as running a big gas truck would. I spent $133 at three Tesla chargers, getting a total of 268.32 kWh of energy. I then spent $82.11 on other charging networks, for a total of $215.11. Sadly, my receipts didn’t show what energy I got from them. However, I do know that I drove the truck about 600 miles in total. In other words, the truck cost me just under 36 cents per mile to operate.

For comparison, I averaged 10.2 mpg towing the family camper with a Ford F-250 Super Duty Power Stroke. Based on its 34-gallon tank, that means a range of 346.8 miles, or a little less than double what the Silverado EV could do while towing the same trailer. That truck would consume about 58.82 gallons over the same 600 miles. At current diesel prices in my area, which are about $3.80 a gallon, that adds up to $223. So, the Silverado EV is about as expensive to run on public chargers as a diesel truck.

Like A Diesel, But Quiet

I even did some mild off-roading with the truck, as the camp at AirVenture got seriously muddy. The Trail Boss rode through soupy mud like it was nothing. Now, I have no doubt that this truck would struggle with crawling over rocks or through terrain serious enough to warrant lockers, but mud, fire roads, and mild to moderate terrain? Yeah, the Trail Boss could handle it.

Even with this truck’s faults, I was thoroughly impressed. It was freeing to be able to take a long-distance trip in an EV without worrying about running out of charge. I was blown away by the truck’s diesel-like towing performance, soft suspension, and library-like quietness. General Motors did its homework with this truck, and I think it makes a passing grade.

But the truck doesn’t get a perfect grade. I cannot discount the problems that I experienced with the truck’s interior fittings and with Super Cruise. Then there’s the price of it all. The 2026 Silverado EV has a base price of $54,895, which isn’t bad until you realize that it gets you a work truck with few features, rear-wheel drive, black bumpers, and steel wheels.

If you want some style, that’ll cost you $62,995 to get you into the LT. If you want a Trail Boss with the Max Range battery like the one I had, that one starts at $88,695, and then escalates with options. According to my press truck’s window sticker, the folding tonneau cover was $1,850, then other additions included a $1,800 glass roof, and a $1,495 tailgate with a step and an integrated Kicker boombox. The end price? $93,940, which includes a $2,095 destination charge.

To put that price into perspective, that kind of dough would easily buy you a Ram 2500HD heavy-duty pickup with a Cummins diesel engine, with nets you significantly better payload and towing capacity. That said, you can save on a Trail Boss by getting one with the smaller Extended Range battery, which is good for 410 miles for $72,095.

To me, the biggest problem with the Silverado EV is not the truck or its price, but the infrastructure that supports it. This is a truck designed to tow trailers long distances, but America’s charging network isn’t yet built to handle people who use EVs for work or for towing. Nobody wants to decouple from their trailer every single time that they need to charge the tow vehicle.

America’s questionable charging infrastructure also harms innovative camper trailers like the Pebble Flow and the Lightship AE:1. If you cannot easily charge a truck while it’s connected to a trailer, imagine the headache of trying to charge both your truck and your trailer at the same time.

This puts the Silverado EV in a weird place. In some ways, it’s better at towing than a diesel truck. Certainly, EVs flex their towing muscles without fumes, diesel maintenance, or diesel pollution. But charging sucks so much that it’s easier to keep burning fuel, anyway.

So, I think the best way to describe the Silverado EV is that it’s one of the best trucks for a future that isn’t here yet. It’s a towing beast, can outrun darn near any gas-powered vehicle in a stoplight drag, and is the first electric truck that I’d feel comfortable driving across the country. In short, it rocks. But America just isn’t ready for it yet.

Top graphic image: Mercedes Streeter

I do not get it.

Half ton is 500kg. Which is 1102 lbs. Crappy pick up trucks weight 9000lbs which is 4082kg, or 4 tons. Nowhere close to half a ton. It is a 4 ton truck that gets cost the same to charge as F250 diesel getting lame 10MPG.

I thought EVs were supposed to be cheap to drive in. My GTI gets 33MPGs average, 3 times less fuel cost than lame GM EVs.

Maybe the EV savings are $100/year from engine oil changes and less brake pad use?

Also going slower when towing would use less power as there is less air resistance. You should drive more miles per kWh at 30mph than 70mph

It refers to the payload capacity, not the weight of the truck

They simplified, but they didn’t add lightness. Did GM even own Lotus, or is that just my headcanon escaping containment?

Last summer we did a family vaca and we took my Son’s Lightning. While charging at a WalMart EA in Montana a guy pulled in with a Silverado EV. We talked as one does and compared. He is a Sparky and uses it to tow his job trailer around the area. I forget the exact specs he stated but it wasn’t light or small sounding.

He said he preferred the look of the Ford since it “looks like a real truck, instead of this Avalanche looking thing. The lower hood does make for a smaller Frunk than the Ford. Other than some glitches with the fob not always being recognized he hadn’t had any problems with it. He did say he was about to buy a Ford since he couldn’t find the Chevy and ended up finding one in Denver that he did a fly and drive. Overall he was happy with it and did what he wanted it to do. Note, he did not have his trailer connected when he pulled into the lot.

Hey I see you stopped by my Woodmans in Menomonee Falls! Is it just the Trucks that slow charge on the Tesla network? Or are all Utlium platforms having that issue?

8,500 to 9,000 lbs

Amazing!

Heavy Chevy

THat is 4 tons, not half of a ton yet they insist it is 500kg truck

Again, it refers to the payload capacity, not the weight of the truck. And it’s in lbs, not kgs. And the ‘half ton’ moniker at this point is just a legacy term for “light duty” or F-150s or Silverado 1500s or Ram 1500 and the like.

“If you have a poorly built camper…”

Isn’t that tautological?

If you have water that is wet

Wow, a big lead up to how good it tows and then you finaaaaly admit the range and surprise! It does not tow like a diesel. As you read the article the truth of this truck is forced out. This truck is a showy EV just like the rest. The material is cheap shit like GM loves no matter the car you get from them and you are a sucker if you buy this and actually plan to tow more then the lawnmower over to moms to help her cut the grass.

Actually, it sounds like just the thing for a professional landscaping outfit that rarely leaves the metro area they’re bases in, can charge at the yard overnight and pulls a couple of big zero-turn mowers to a job site on a flatbed trailer.

How does the extra cost, 2 trucks worth, make that make sense? No business will do that. The owner might buy one to be cool, but the workers won’t get anywhere near one of these if an owner had any sense.

A base EV starts at $55k. The diesel RAM starts at $68k. 7.3 Ford starts at $77k. If you’re towing something heavy for short distances, it can make sense.

Except most of the landscaping trucks I see are bought used, unless the company is loaded. The other thing is that there still needs to be the OPTION of having more than a little over 100 miles of range in a day, which is probably where people get cold feet about this. Landscapers aren’t always gonna be hitting a single house in a day

To charge GM EVs it costs the same as buying diesel for F250 that gets 10MPG, and F250 will get a full tank of fuel way faster.

What was the point of GM EVs??

I’m unsurprised that it tows well. It’s heavy as sin with that weight mounted low. It would take a hell of a tail to wag that dog.

Now who’s gonna sell me a half ton with a 60-70kWh battery and an onboard range extender? WE’RE WAITING.

I’d be scared to have something that weighs almost 5 tons near mud. Also can they stop making these things have a head snapping 0-60? Does anyone care at this point that you can go whirrrr in a straight line, I figured everyone was on the same page about it mostly being a party trick that’s extremely dangerous in the wrong hands

The corollary of a big battery is big power potential. No reason to leave it on the table even if it’s unreasonable.

Other than the fact that it represents a meaningful risk for everyone outside of the pickup. Not that the car companies or owners care about that.

No, it weights half a ton

Would you stop with that?

I love Robert Dunn’s take on things and how he tests. He also noted the shockingly bad quality of the Silverado EV.

The issue with BEV trucks is that they suffer more acutely from the weaknesses of BEVs in general. They require you to carry around a battery sized for the worst-case scenario when it is rarely needed. So the vehicle gets very heavy and very expensive.

Meanwhile, retail charging tends to be more per mile than ICE (see the Aging Wheels video for a good, detailed analysis), and a huge PITA if using the truck for towing.

So, unless you are regularly using a BEV truck for towing within the range of your home charger, they don’t make sense. They are more expensive to buy (and have terrible depreciation), less capable, and more costly to fuel anywhere other than home.

The Silverado’s other failures, terrible quality control, inability to calculate range while towing, etc. are due to being a GM product and not a general BEV issue.

Complaining about charging infrastructure is pointless. There is zero incentive to improve it in any meaningful way. There is no money to be made on charging, and since retail charging is already more expensive per mile than gas, consumers are incentivized to avoid retail chargers wherever possible. Not a business model with much hope. Gas stations today make money on selling chips and Coke, not gas, and that model requires the high turnover that comes with quick fueling stops, which isn’t possible with EV charging.

Until batteries improve significantly, BEV trucks will be a niche option primarily used for fleets where they can charge at a central location overnight and then spend the day zipping around within a radius of 100 miles or so. Or, as a massively oversized and overpriced commuter vehicle that takes occasional trips to the local lake towing the family boat. Long-distance towing is still not a reasonable use case for BEV trucks.

You’ve just described like 80% of consumer half-tons. And since trucks like the Lightning are priced pretty competitively with gas trucks, they have many advantages over gas for the vast majority of their use case, and just occasional disadvantages. Objectively, they should be far more than “niche” considering the use case of consumer trucks.

The BEV Silverado showcased in this post requires a $27k premium over the ICE model. Without the extended range battery, it is still a $12k premium. Bluebook on a 2022 standard range Lighting Lariat is $37k, 53% depreciation. On a 2.7T F150 Lariat, the depreciation is 26%. So two years of ownership costs the person who purchased the Lightning $23,000 more in depreciation. No amount of home charging will ever make a BEV truck worth it.

Plus, the entire point people buy trucks and then end up using them as commuters is that they want the appearance of being able to do truck things and to have those occasional truck-based functions to be easy. Towing any distance in a BEV is such a PITA that it would be better to rent an ICE truck when you need that function. Then you could just get a good commuter BEV that costs a fraction of a BEV truck and is far more efficient.

The fact that consumers make poor decisions that lead to them being used as commuters doesn’t make BEV pickups make sense.

I said Lightning, not Silverado. But even in THAT case, after the $7500 tax credit, now it’s only $4500 more (and that’s assuming your comparison points are apples-to-apples).

One, this is incorrect because it ignores the $7500 tax credit. That’s probably why KBB (your own source) says 2022 Lightning depreciation is 30% over 3 years. Two, it’s completely irrelevant to people buying NOW, which is what we’re talking about. Lightnings were selling for MSRP or higher back then, so yeah, their depreciation was higher (not to mention huge changes in the EV market that were unique to the time period between 2022 and now). Now, plenty of people have bought *extended range* Lightnings for low 50s or even high 40s, very competitive with gas, and will have far lower depreciation than your claim.

My Lightning cost $35k, new, less than the cost of any new 4-door F-150. I started ahead and the savings started growing on day 1.

You admit that most people are buying trucks for appearances, then pretend like long-distance towing is a common use case for these people. It isn’t. TONS of truck owners never tow long distances.

You say people buy trucks for appearances, but then pretend there’s any chance they’re going to buy a “good commuter BEV” instead. You’re arguing against trucks *in general*, not BEV trucks.

If people are just buying trucks to use mostly like cars (which we both agree is a substantial number of truck owners), then those people are often better off buying a BEV truck that’s has a huge frunk, is cheaper to fuel, quicker, quieter, has the convenience of home charging, etc. rather than driving a super-inefficient gas truck around for “appearances.”

Heavily discounted prices aren’t a valid measure of market value—they reflect overproduction, which Ford has already addressed by scaling back output. Anecdotes are equally meaningless, since one could just as easily present examples that contradict your experience. My observations are about the market as a whole, not any individual’s situation at a specific moment.

For context, the base price of a 2022 standard-range Lightning Lariat was roughly $68k. With options like the extended-range battery, it could exceed $80k, so a fair baseline is about $70k. Kelley Blue Book now shows a low-option standard-range Lightning valued around $33k.

I’m not interested in historical markets, incentives, coupons, or a deal that popped up online once—only current conditions based on MSRP. Unrepresentative anecdotes hold no weight.

Yes, I am pointing out issues with trucks as commuter cars. That is a reasonable critique. The appearance that people want with a truck is that it presents to others that they use the capabilities inherent in a truck. A BEV truck doesn’t really do that because of its limitations.

So, back to the original point. BEV trucks are niche vehicles. For fleets and the few people who regularly haul and tow short distances, or otherwise just need a commuter vehicle, and don’t care about what most truck buyers care about, looking like they need a truck.

The only thing that matters is what people are actually paying. Tons of vehicles sell for way under MSRP and pretending that’s not true means your arguments are irrelevant to actual buyers.

Base price was $67,500. After tax credit: $60,000. Zero-option 2022 Lariat with 40,000 miles: $35,400 on KBB. That’s 41% depreciation, way below the 53% you claimed, and again, that’s not accurate for people buying NOW that would get many additional discounts, resulting in paying less than $60k AND getting the big battery.

Your claim isn’t even correct for 2022, and is even more incorrect for the current market.

It’s impossible to talk meaningfully about the American truck market or the EV market while ignoring discounts and credits off of MSRP.

Yeah, I already agreed with you that many truck owners don’t really NEED trucks. That’s why many of those people would be better off with a BEV. Sure, they’d also be fine with a Model 3 or Bolt, but it’s a moot point. They’re not going to trade their gas trucks for Bolts. They would get the same “look” with a BEV truck, though, plus a ton of other advantages.

(Hauling has just a small effect on range. It’s basically negligible for overall discussions)

If we add up the number of trucks that fit into the following categories:

-Fleets

-People who never tow

-People who only tow short distances

That’s a number of trucks that is way, way beyond “niche”.

How about this? You can have your opinion, and I will have mine, and we will see what happens in the market. We will see what percentage of full-size trucks sold are EVs and what percentage aren’t.

How about this? You can have your opinion, and I will have mine,

The data I provided about pricing (2022 and current) as well as depreciation are not “opinions.” The fact that tons of people drive trucks but would be fine driving cars is not an opinion, and you agreed. That many people either rarely or never tow is not an opinion. That lots of trucks are fleet trucks is not an opinion. The advantages of EV trucks are not opinions (frunk, lower fuel costs, etc.). You can’t refute those facts, though, so you pretend they’re conspiratorial “opinions.”

I didn’t claim that full-size truck buyers WOULD switch to EVs in the short term. Just like people drive trucks instead of cars/hatchbacks/wagons for irrational reasons, which you stated also, they may also make irrational/ignorant decisions with regard to choosing a drivetrain.

It doesn’t change the accuracy of anything I said whatsoever even if no one ever buys another BEV truck.

Which is the part you disagree with? The thing that seemed to trigger you was the idea that they are “niche” vehicles. The only counterargument would be sales. But once that is presented as the measure, you have a tantrum and say sales don’t matter.

Get over the insecurity you have about your purchase that causes you to need to defend it past all rationality. Nobody cares enough for it to matter.

My posts are very clear. I literally quote the things I disagree with for clarity.

Wrong. The other counterargument, which we’ve been discussing for several comments, is that the BEV trucks already cover the real use cases of actual truck owners – a massive number of which are somewhere between “just buy a truck for appearances” and “rarely tow beyond 50 miles”, and BEV trucks are easily argued to be superior for those use cases.

“Beyond rationality” is ignoring your own contradictions and then trying to psychoanalyze someone else to salvage a flimsy argument.

Your own claims show that BEV trucks are capable of being far more than “niche” vehicles:

-You claim that they work for fleets (a large percentage of truck sales)

-You claim that lots of people buy trucks for commuting or simply for appearances (another substantial percentage of truck sales)

Combine those two of *your* claims, and it’s obvious BEV trucks have far more than “niche” capability.

If your point was just about sales, you could have said that after my very first response. Instead you kept using erroneous numbers and flimsy arguments until they all failed, and then you moved the goalposts to sales.

Sales matter for the manufacturer, but they don’t change the reality about capability that your own claims admit: BEV trucks could easily replace a substantial percentage of current trucks. They’re objectively a better option for far more than a “niche” amount of truck-owners’ use cases.

Your delusion seems to be the gap between what you think should be true and what is true in reality.

Whether BEV trucks CAN do the things that most truck buyers need is largely immaterial because truck buyers don’t buy trucks because they NEED a truck. The things that BEV trucks don’t do well are the things truck buyers WANT to do. Or at least want to be seen as doing.

So, the original statement remains completely, irrefutably true and has never varied. Goalposts remain where set initially despite your clear dishonesty.

This will be backed up by sales figures moving forward. Your personal hopes and dreams backed up by meaningless anecdotes are, as always, 100% meaningless.

Nope. I’m talking about the reality of capability vs perceptions/sales.

I’m not saying sales are great or WILL be great anytime soon, but EV trucks are objectively superior for many common use cases, which you admitted, as well, stating multiple times that truck buyers buy trucks for appearances or what they wish they used trucks for, but don’t.

Yes, glad we can agree. BEV trucks are a “niche” as far as sales, currently (you didn’t specify sales vs capability originally), but they’re nowhere near “niche” as far as capability, especially considering all their advantages.

Wrong. It remains “completely, irrefutably” ambiguous. “Niche” is vague as far as whether it refers to sales or capability.

And you made several other false or overgeneralized statements originally, also. For instance:

Overgeneralization, at best.

Overgeneralization, at best.

(and have terrible depreciation)

You exaggerated the numbers, and ignore the unique EV situation over the last few years.

Overgeneralization. In some ways they are MORE capable. Far quicker, far more enclosed storage (huge frunk), standard power outlets (can power the essentials of a home for many days after a hurricane, for instance), home charging convenience, etc.

Overgeneralization

Plenty of places are effectively free to charge or still comparable/cheaper than gas for an overall trip.

Complaining about charging infrastructure is pointless. There is zero incentive to improve it in any meaningful way.

Is that why Tesla went from no network to, by far, the best network that allows for easy nationwide travel to most locations?

Nope. You made tons of claims as to why BEV trucks weren’t as good or capable or cost-effective as evidence for your “niche” claim, but when your claims were refuted, you moved the goalposts strictly to “sales.”

Nothing I’ve said is even remotely dishonest. No surprise, you didn’t include an example.

But you, on the other hand, have provided many claims that are either dishonest or based on ignorance, so the only thing you’re holding onto is sales so you can avoid all the other erroneous claims you made.

Again, the combined total of

Fleet

Trucks used as commuters

Trucks used as commuters/local towing

…is objectively not a “niche”. The combined percentage of trucks that falls into one of those categories is a substantial percentage of truck sales.

The fact that you made flawed assumptions, such as dishonestly claiming that my original use of “niche” meant “BEV trucks weren’t as good or capable or cost-effective”, isn’t my problem. The general definition of a niche vehicle is one that, due to its total collection of characteristics, appeals to a limited audience. The fact that you dove headfirst into a reality where only the values inside your head matter simply highlights your obvious narcissism. The only reasonable measurement, therefore, is sales to everyone. Not just what some lonely narcissist on the internet thinks people should buy.

My original statement remains 100% accurate. If you want to be pedantic and dive into the minutia of sales prices, depreciation, etc., fine. But none of it changes the outcome or makes my statement untrue. It would be like you arguing fouls after you lost the game. All your ranting about free charging options and the things you value will come to nothing because everything in the real world has shown you are wrong. People don’t value what you value, and all of your ranting is just you stroking yourself with no payoff.

BTW, Tesla built the charger network to sell cars. That was their incentive. Incremental charger installations have an ever-reducing impact on BEV sales. Meanwhile, retail charging makes little to no money, and incentives are essentially going away. There is little to no incentive to expand the charging network.

Here are a couple of sources that explain.

Anthropomorphic climate change is real, and Trump is a fascist, but I can’t change that fact as much as I wish I could. But deluding yourself into thinking BEV pickups aren’t a niche vehicle is just making things worse, since it avoids dealing with things that matter.

Cool story, but the lead up justification for your “niche” claim was a bunch of claims about “less capable”, “more expensive”, etc. You know we can just read what you wrote in your original post, right?

But keep pretending I’m the one that’s dishonest.

All of your reasons for claiming it was “niche” were untrue or exaggerated, which is why you’ve now glommed onto “sales” and are avoiding all your other reasoning that has been debunked. That people believe the same false information you have regurgitated is a part of why sales are low.

And sales ARE low. No one is arguing they aren’t.

But your claims about cost or depreciation or niche capability are false/exaggerated, and it’s not dishonest to point out misinformation.

So, when you said there’s “zero incentive to improve it”, that was false. Glad we agree. The reason is to sell cars via improved capability and ownership experience. Which is also why Ford/GM/everyone switched to the Tesla port and got access to Tesla charging; because they saw substantial value in improving their charging network.

They’re definitely niche sales, currently. I never said otherwise. But there’s a big gap between the size of the sales niche and the capability/use case niche, partly due to bad info around cost, depreciation, capability, advantages/disadvantages/etc., which you used to support your “niche” claim.

God, you are an idiot. I used the term “niche”; you don’t get to define it as you want, just because you are an insufferable narcissist. Why on earth would anyone think that my use of “niche” meant “in capability” rather than the broader, more applicable, and much more meaningful sense of adoption/sales? I won’t engage with you on the rest because you have made it clear you aren’t capable of even accepting the correct starting point. If you change your mind. We can get back to the other items. Until then, there isn’t a point.

You keep providing perfect examples of your dishonesty. Obviously, my statement “There is little to no incentive to expand the charging network” means in the future. Expand means to increase from its current state, if you weren’t aware. I even provided links to show this reality. Yet you are so fundamentally deluded that you can’t grasp this and attempt some sort of time warp to say that the factors now are the same as they were when Tesla started selling cars. But you are too dense even to understand how time works.

But the best part of your latest comment is when you blame the lackluster adoption of BEV trucks on the fact that not everyone shares your delusion. You truly are an irredeemable narcissist.

Actually, as already discussed, “niche” could be a reference to sales or a reference to capability. There’s a huge difference, and you didn’t define the term, but made claims about cost/capability that were false, so I responded to those.

Nice try though.

Do you know what “dishonest” means?

The future has the same issue for charging infrastructure as the examples I gave. Using Ford as an example, if infrastructure doesn’t grow with total EV sales, the charging experience will trend toward how it was for Ford before they got access to the Tesla network – charging was famously painful, which means fewer people buy Fords than if they had easy/reliable charging. So, they have an incentive to expand their available charging network. It’s not hard, and there’s nothing here anywhere near “dishonest.”

Oops, can’t refute the actual points, so you resort to personal attacks.

Remember when you said that people buy trucks (instead of cars) based on capability they don’t need despite it being a bad financial/efficiency/etc. decision?

But when I say the same thing; people buy gas trucks instead of EV trucks based on capability that they don’t need at the expense of TCO/efficiency/other advantages, I’m an “irredeemable narcissist.”

Cool story.

Try being objective and well-informed on the topic so you can argue facts instead of just regurgitate Facebook-level claims about EV trucks and call people names when you’re out of your depth.

What niche “could” mean. But it didn’t. Are you so unable to understand a clear context that you need to have every work so narrowly defined? If so, English isn’t going to be your strong suite. Your attempts to define it narrowly by your terms and force me to defend it, is why you are clearly a narcissist. The fact that you can’t let go of this mistake is why you are an irredeemable one. Don’t like it, change your behavior.

Again, I would be happy to go back to the details about costs and depreciation if you could look honestly at the starting point. But you lack that ability. So, there is no reason to engage on any other points because you have shown you are dependent on dishonesty to make your points.

I do appreciate you continually providing examples of your delusion. Tesla only sold BEVs and was very reliant on a charging network when one didn’t exist. For Ford and most other car makers, BEVs are a tiny fraction of their sales, and once incentives go away, they will be an even smaller percentage. Not that they mind, since they are low-profit models anyway. So, they don’t need to care about the BEV charging experience. Without direct incentives, the network expansion will be minimal at best. I gave you links to prove my point. Yet you are incapable of dealing with current facts, and instead try to suggest that the conditions now are the same as they were when the Tesla network was initially built. Again, you are either willfully ignorant of current conditions and reality or simply attempting to dishonestly frame the conversation, again.

Let’s reset. Pickups are currently purchased primarily for irrational reasons. So, attempting to rationalize BEV trucks in the way you are hoping to do is largely immaterial. As incentives go away, BEV trucks will be significantly more expensive than ICE models, which have greater capabilities at the things truck buyers want when they buy a truck, rational or not. BEV trucks might be better than ICE trucks for commuters, but there are numerous other options that are better than BEV trucks. Add to that the fact that BEV trucks have higher depreciation, standard retail charging (the type people can count on when deciding between BEV and ICE options) is more expensive per mile than gas. We can add the fact that an estimated half of the households in the U.S. can’t install or get access to a level 2 charger to take advantage of residential electrical rates.

So, in every way that matters, BEV trucks are a niche vehicle and will be for the foreseeable future. The charging network expansion will come to a near halt now that incentives have been largely removed. As shown by the links provided earlier.

Imagine pretending you “clearly” meant “sales” when the lead up support was claiming that BEV trucks were “less capable.”

Totally dishonest considering we can just go read your posts, still.

But, it doesn’t *really* matter what you meant with your ambiguous “niche” claim. There were plenty of erroneous claims you made that I thoroughly, directly refuted.

We agree that they have niche *sales*, so there’s no argument there. And you effectively admit that they’re NOT niche in capability for trucks because you admit they are plenty capable for fleets, commuting, and local towing, which, in reality, accounts for a huge number of current truck owners.

You are trying to keep the focus on the “niche” discussion to avoid the direct claims you’ve made that have been refuted and you can’t defend.

Hahahahahaha

Imagine telling someone they aren’t good at English and in the same sentence, you misspell “suit”. Classic.

Your claims have already been proven false, even using your own sources (KBB).

You made up a fake, erroneous initial price and then a low current value to exaggerate depreciation, but your own source said you were wrong.

It’s all right above this post in black and white.

Sorry. Pretending you were correct is fun, but not reality.

Completely dishonest, but claiming I’m being dishonest. Classic move when you can’t argue facts whatsoever. Just keep attacking character and pushing semantic arguments.

Is that why Ford is spending $5 Billion on a new EV platform to underpin several models, killing their best-selling CUV for 2024 in the process?

Another fun story, but not reality.

Not only is your entire premise wrong, as I already explained (manufacturers have incentive to not let their charging infrastructure deteriorate back to where it was before they got Tesla access), but your articles are completely wrong. The Trump administration reversed their removal of the EV charging credits.

You are very poorly-informed on the topic of EVs, costs, capability, charging, etc., so your only fallback is character attacks and pretending that you were right when you were demonstrably wrong.

The exact conditions are different, but the issue is the same: Bad charging experience means poor sales, which incentivizes infrastructure investment. It was true then and true, now, which is why manufacturers are supporting their own networks, now, like Ionna (several manufacturers), GM+Pilot, Mercedes, etc.

As incentives go away, BEV trucks will be significantly more expensive than ICE models,

Speculation. If you look at pricing for Tesla and GM BEVs after they lost the $7500 tax credit the first time, their ultimate pricing was essentially unchanged.

Again, poorly informed about EVs.

Gas trucks are better at some things people want, and EV trucks are better at other things people want, like enclosed storage (as evidenced by the number of trucks with tonneau covers and/or toolboxes in the bed) or performance or fuel costs (as evidenced by the complaining when fuel costs go up) or home charging convenience or powering one’s home in a power outage (as evidenced by the people who buy generators). The list goes on.

No one is pretending that people currently LOVE BEV trucks or that there aren’t advantages for gas trucks, but BEVs have several objective advantages, as well, and despite perpetuating bad information on cost, depreciation, capability, etc. makes people THINK they’re making a rational decision when it’s irrational.

And fleet trucks that are used as trucks, and trucks used as trucks by local contractors, and trucks occasionally used locally as trucks (towing/hauling/etc.) by retail buyers… the list goes on.

Way less depreciation than you claimed, and now it’s likely even lower if someone purchased now. It’s also only one part of TCO, which also includes initial cost (similar), “fuel” cost (lower), insurance, maintenance, etc.

Most people will charge at home, so focusing on retail charging is pushing an irrational decision.

60% of households are single-family detached homes. Most of those people could add a charger. Plus some other people who don’t live in single-family detached housing. PLUS, people buying new full-size trucks are almost certainly far more likely to live in single-family detached housing than the average person.

ALSO, L2 is also not always a necessity. Mine charges primarily by L1 120V charging.

You’re providing a Facebook meme level of analysis of BEV trucks with many erroneous claims. You’re good at name-calling, though! Unfortunately, you’re not well informed about BEV trucks, which is the actual topic.

At some point, it would be best if you chose to exit your self-made pedantic prison and deal with reality. You can try to move the pieces around all you want, but the conclusion will remain the same and be proven out.

BEV trucks are a niche product in any way that matters, and the charging network expansion will continue to slow. But continue to stroke yourself with your delusional pedantry as long as you like. I just recommend you get your blood pressure checked.

At some point, it would be best if you stop avoiding the fact that most of your claims have been proven false*, and so you’re hiding behind the fact that BEV truck sales are low, which no one disagrees with.

What I disagree with is perpetuating false information about BEV trucks and then wondering why people think they’re making a rational decision by choosing gas.

Just a few of your many false claims, so far:

Wrong. You ignored the $7500 tax credit

Wrong. More like 41% based on real numbers, not fake numbers that use MSRP when there is a $7500 tax credit. It’s also more in line with what your own source (KBB) says.

Wrong. Hauling has little effect on range.

Wrong. The linked articles are incorrect. Trump reinstated the funding for EV charging AND even without it, there is substantial incentive for manufacturers to avoid allowing people to have a terrible experience charging their vehicles.

You’re just not well-informed on the topic of BEV trucks, so you google something really quick or remember what you read on Facebook or an article from someone who also doesn’t know anything about the topic (hauling bad!), and then your only remaining argument is “BEV truck sales are low!” which no one disagrees with.

Brush up on your knowledge a little, and we can continue this some other time.

Feel free to have the last word, if you want. Turning notifications off since your only remaining argument is one we both have agreed on since the beginning (low BEV truck sales).

If it is a 7500 discount why am I paying full price or paying interest for full price?

My income taxes do not change EV prices at all

It’s been a point-of-sale discount since January 2024.

Even under the old system, this is a hilariously bad take. Yes, if I pay $7500 less on my taxes because of buying an EV, that absolutely changes the real cost of buying an EV compared to MSRP.

Maybe *you* make too much or too little to take advantage of the credit, but a huge change in taxes paid is definitely a consideration for many people.

Yet you still have to write a check or get a loan for full price, they won’t sell you crappy Ev truck for MSRP-7500, only for at least MSRP

If it is a 7500 discount why am I paying full price or paying interest for full price?

Sorry to hear about the coma you’ve been in for the last year and a half.

The tax credit has been available at “point of sale” since the start of 2024.

Aging Wheels is one of my absolute favorite YouTube channels. The guy’s covering stuff no one else would ever bother with, he’s smart, and very funny.

For sure. He is just so damn clear on how he evaluates things. It makes it truly helpful. He really likes his BEV Silverado, but isn’t afraid to call out the terrible quality and, more importantly, the fact that, unless you are towing in a bubble around your home charger, they cost more per mile than an ICE truck.

Since he has made it clear that he can’t afford to keep the truck and will need to sell it within the year, it will be interesting to see how he feels about the off-a-cliff depreciation.

It’s honestly shocking how broken his unit is. After watching his video I had to go outside to see if the DRLs and turn signals were the same brightness on my tester. Thankfully, they were…but what the heck, GM?

First thing: space dress is AWESOME. Heck, I’d wear that and I’m a dude. (It’s a tunic and kilt, honest officer!)

Second thing: 7500# is a typical two-axle horse trailer. The Silverado EV is quite attractive for hauling animals because smooth acceleration/deceleration is top priority, and 200mi is about what you might want to do in a day if you’re not transporting cross-country.