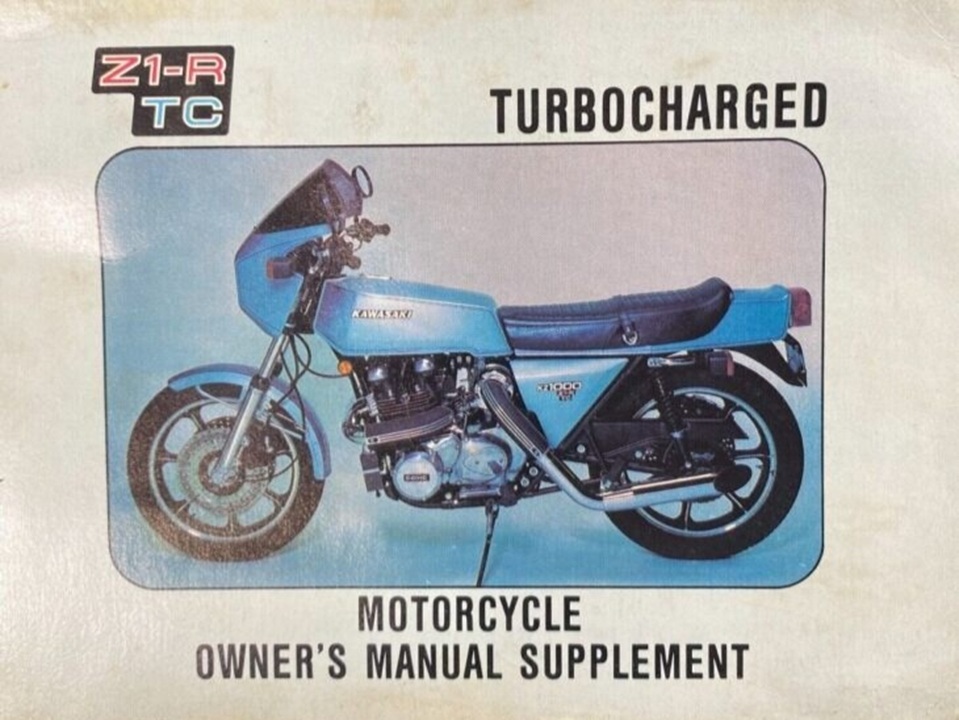

Turbocharging is about as foreign a concept in the motorcycle world as diesel power. Only a handful of motorcycles in history have experimented with forced induction, and the most famous examples have superchargers, not turbochargers. Most, but not all; back in 1978, a company produced the world’s first turbo motorcycle that you could buy from a dealer. The Kawasaki Z1-R TC (you can guess what the TC stood for) was a marvel of engineering. It was also so wildly unpredictable that you couldn’t get it with a warranty, and you had to sign a waiver just to buy it.

The greatest and perhaps weirdest period for Japanese motorcycles was the 1970s and the 1980s. The nation’s motorcycle manufacturers were not much different than car manufacturers in that innovation, quality, and performance were paramount. Just like the automakers, bike builders wanted to flex their engineering muscles. This led to fantastic machines like the Yamaha RD350, the Honda CBX, the Honda Gold Wing, the Honda VFR, the Yamaha VMAX, the Suzuki GSX-R750, the Kawasaki GPZ900R Ninja, and so many more.

This was also the period when the Japanese Big Four experimented with the world’s first production turbocharged motorcycles. The reasoning back then wasn’t much different than applied to modern turbocharged cars. The motorcycle manufacturers thought that if they took a smaller engine and turbocharged it, that engine could have the same kind of output as an engine perhaps even twice its displacement. At the same time, since these engines were small, they should offer great fuel economy when not in boost.

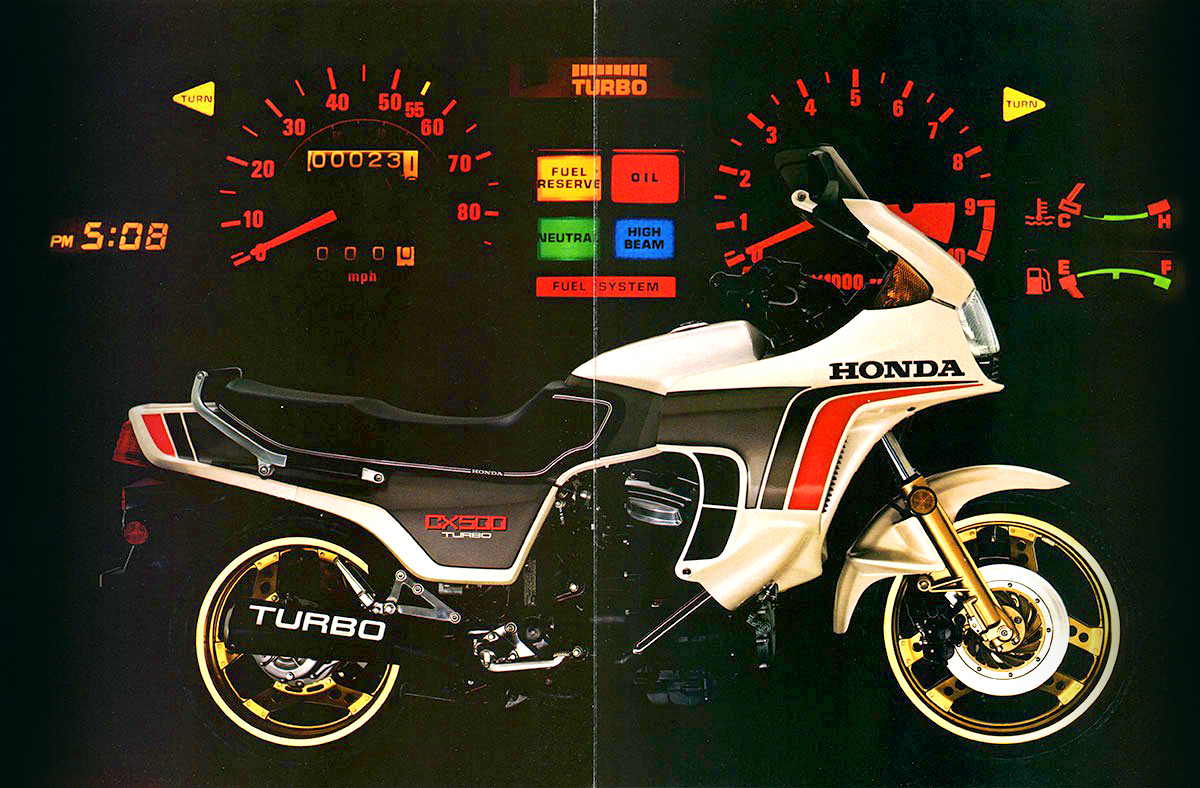

The 1982 Honda CX500 Turbo was Japan’s first true production turbocharged motorcycle, but it wouldn’t be by itself for long. Honda’s technology demonstration was quickly followed up by the Honda CX650 Turbo, the Yamaha XJ 650 Seca Turbo, the Kawasaki GPZ750 Turbo, and the Suzuki XN 85 Turbo. Despite the investment by Japan’s biggest motorcycle firms, the turbo-cycle fad didn’t really last long at all. Seriously, all of Japan’s major turbo motorcycles were dead by the end of 1985. They didn’t even get five years of production.

While Honda was the first to market with a factory-built turbo motorcycle, it actually wasn’t the first turbo motorcycle to be sold at dealerships. That distinction goes to the 1978 Kawasaki Z1-R TC, and it’s arguably the motorcycle that started the whole short-lived fad.

Japan’s Obsession With Power

Japan’s motorcycle manufacturers were obsessed with speed in the 1970s. This was an era when fast wasn’t fast enough, and bikes got faster regardless of how expensive gasoline was. Kawasaki’s relationship with turbos began with the Z1.

Honda’s CB750 Four changed the world of motorcycling when it debuted in 1969. It was the definitive superbike of its day, and Honda’s competitors weren’t keen on letting Honda take all of the glory. Kawasaki, however, was actually right alongside Honda in developing a brutally fast 750 in the late 1960s. One of the hurdles for Kawasaki was moving to four-stroke power. Honda was addicted to four-strokes, but Kawasaki was still hanging onto two-stroke power.

Big two-stroke bikes were living on borrowed time thanks to changing consumer preferences and emissions regulations, and Kawasaki knew the future was in four-strokes. Its new motorcycle, the Z1, was to be developed around a four-stroke engine. Thankfully, Kawasaki wasn’t going into this blind, as it did have some four-stroke experience. It also purchased Meguro in the years before, and that brand also had plenty of experience in the four-stroke arena.

Unfortunately, as Kawasaki geared up to launch a 750cc motorcycle in 1970, Honda beat it to the punch. Suddenly, Kawasaki found itself in an awkward position. Motorcyclist gives more context:

“Before the Z1,” said Z1 development team member Sam Tanegashima on the subject of all-around function in Micky Hesse’s book Z1 Kawasaki, “Kawasaki had developed several very fast motorcycles like the A7, H1, and H2. It was not sure if we were selling engine/horsepower or motorcycle. From the very beginning of Z1 development we made sure to develop one piece of motorcycle, not independent engine or chassis designing.”

In late 1968, as Kawasaki was approaching the point where it would green-light production-parts manufacture of the four-stroke 750 it was developing for the 1970 model year, Honda shocked the world with the surprise debut of its CB750 at that October’s Tokyo Motor Show. The news was devastating to Kawasaki, which understood all too well that releasing its own 750 would likely be seen as copycatting even if the bike was as functionally good as the Honda. And if it wasn’t? Well, that’d be a death sentence for the bike and certainly a black eye for the company.

Other considerations led to pulling the 750cc plug too. During development in ’67, the three slightly different prototype engines they’d built were proving seriously fragile. “The testing done in Japan at the Yatabe circuit,” remembers Kawasaki man Don Graves, “proved that the engines they’d built were not dependable. When the original push from the US asked for a four-cylinder four-stroke machine, Mr. Hamawaki had pushed for a talented engineer from Kawasaki’s aircraft division to be brought in, a Mr. Otsuki, I believe. After all three engines blew up, ‘HP’ [Otsuki’s nickname] began asking for a larger, better engine, hence the 903.”

Beating The CB750

It’s not exactly known when Kawasaki changed its mind, but it was decided that, instead of building a 750cc motorcycle like Honda, Kawasaki would just go bigger and faster. A slew of sketches and clay models were generated and running prototypes soon arrived.

One of the hurdles in the Z1’s development was the tradition of how Japan’s motorcycles were built by that point. Japan’s bikes, like the Kawasaki H1, were known for being wicked fast, but that’s about it. These motorcycles had engines that made so much power that their frames twisted under the weight and torque. But that wasn’t all, as these engines also easily overpowered the brakes and suspension. Basically, if you rode one of these motorcycles, it sort of felt as if the teams that developed the engine and the chassis didn’t talk to each other.

When it came to the Z1, this meant that early prototypes were so floppy that they easily dragged their exhausts in parking lot maneuvers. Soon, Kawasaki realized that, in order to build the king of motorcycles, the whole motorcycle had to be a consistent experience. It couldn’t just build a bike that was good only in a straight line. Kawasaki gathered the motorcycle press to test its prototypes and to help zero in on an optimal motorcycle design.

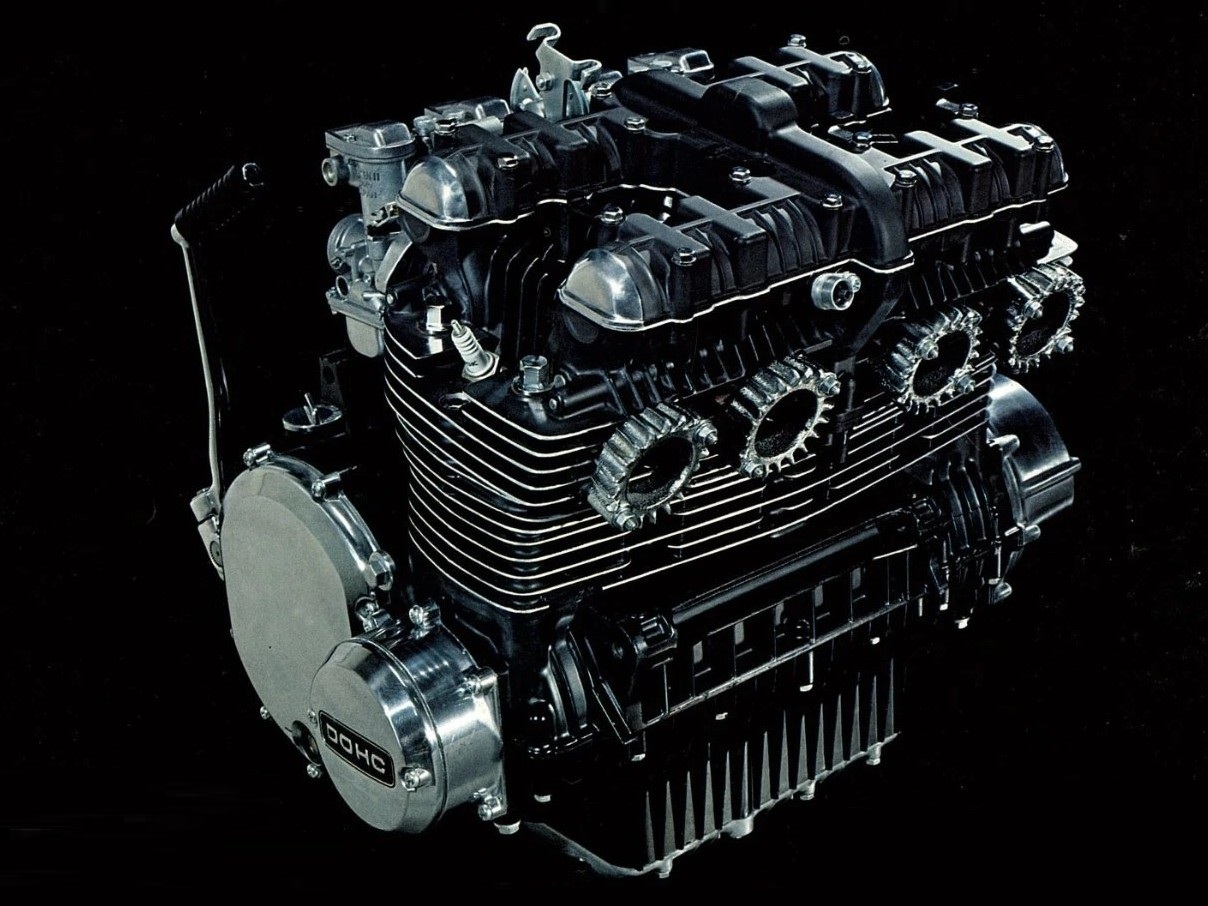

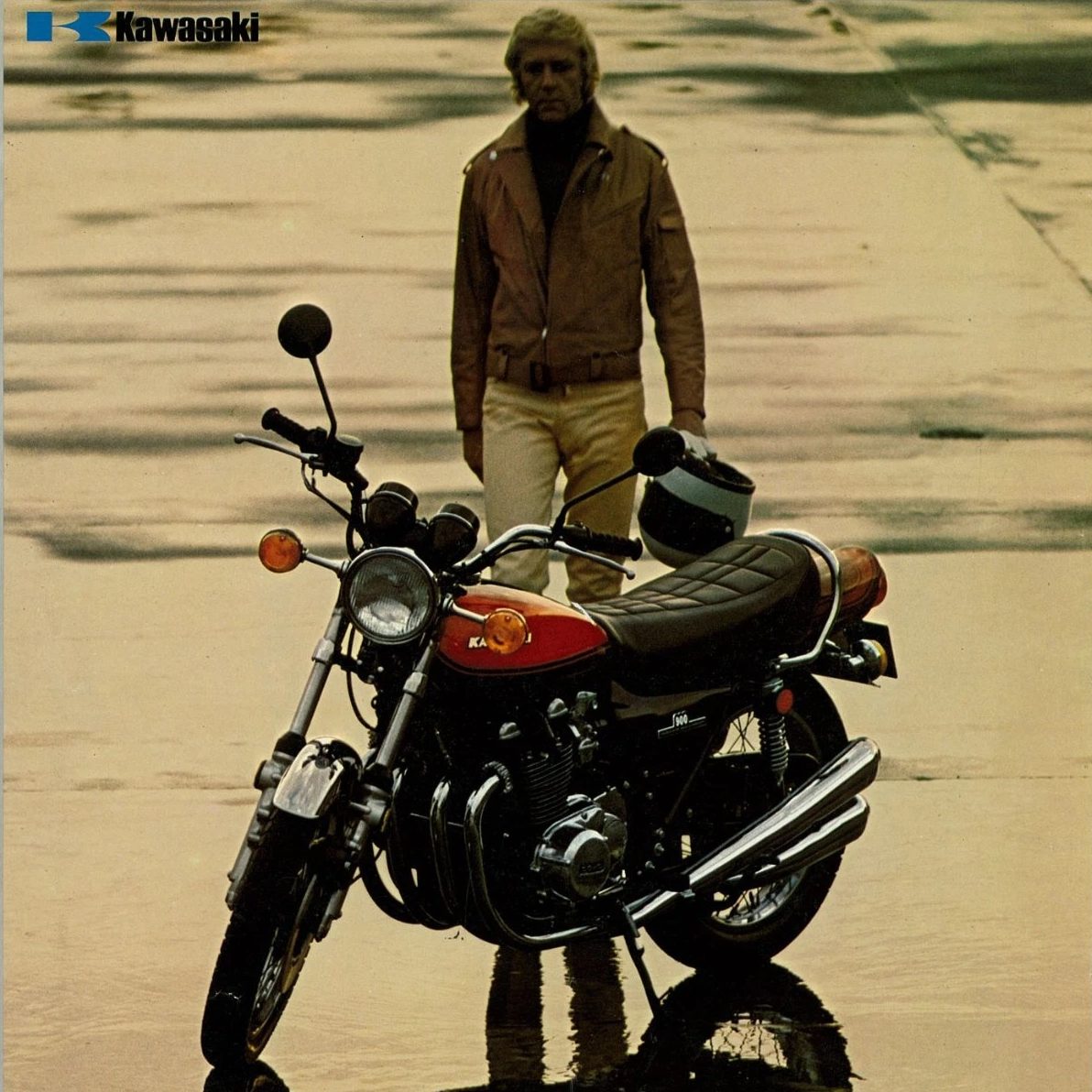

In 1972, the Kawasaki Z1 launched, and it was a smashing success. By integrating the motorcycle press into the development process, Kawasaki crafted a monster. From Kawasaski:

In 1972, the Company unveiled Japan’s largest motorcycle of the day, the Kawasaki Z1, featuring an air-cooled, 4-stroke, 4-cylinder, 903 cm3, DOHC engine, which was Kawasaki’s first 4-stroke engine with a state-of-the-art, unique mechanism. Code-named “New York Steak” as early as in the development stage, the Z1 became a “mouth-watering motorcycle,” winning overwhelming popularity immediately after its introduction, and becoming a long-term bestseller. The Z1, a pioneer of Supersport models, not only solidified Kawasaki’s reputation in large motorcycles, but remains deeply engraved in the public conscience as one of the most superlative models to date.

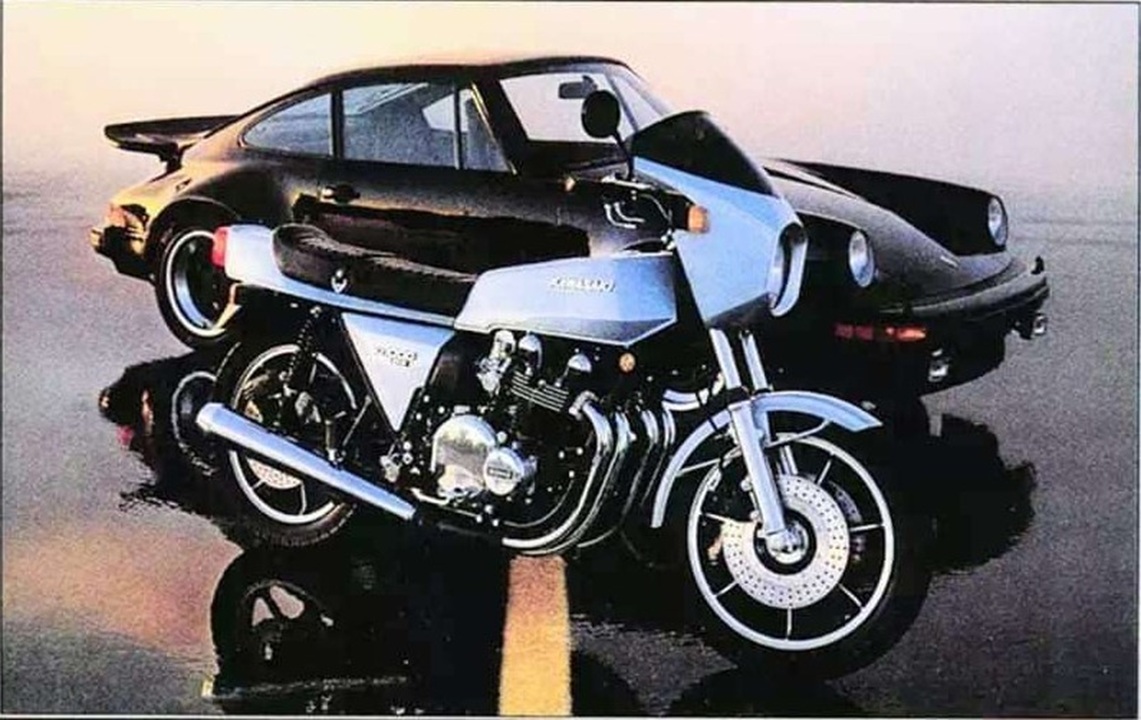

The buff mags went crazy, calling the Z1 the fastest motorcycle in the world, and praising it as the most modern motorcycle on the road. The Z1 broke the AMA 24-hour endurance record, riding at 109.64 mph for 2,631 miles. That bested the previous record by almost 20 mph. But then the Z1 kept winning records, 45 more of them, in fact. One magazine said “Every inch a king…” about the Z1 and it was right.

Kawasaki Loses The Crown

Yet, despite all of Kawasaki’s work, the Z1 wasn’t perfect. It still had a rubbery frame, 36mm forks that couldn’t handle the power, and a rear suspension that was both over-sprung and under-damped. Oh, and the Z1 had a single disc up front and a drum brake in the back, neither of which was particularly thrilled to stop a raging 530-pound machine. In other words, you had to be pretty brave to ride one at the limit.

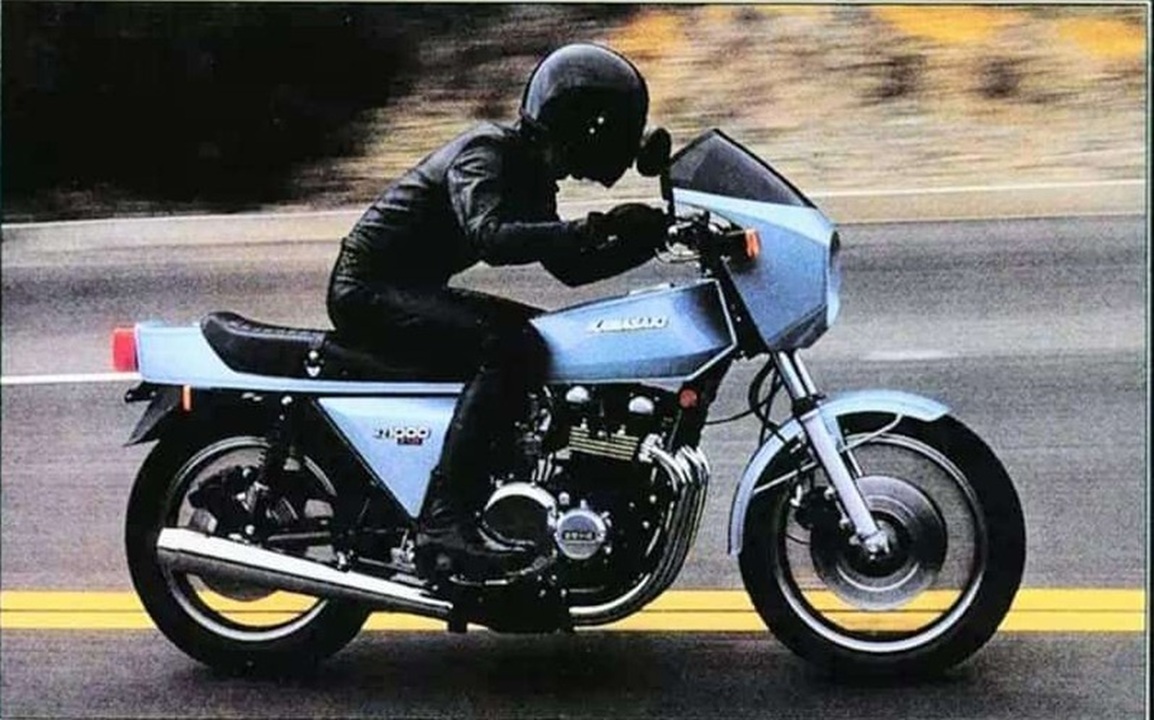

As Cycle magazine wrote in 1978, everything went well for Kawasaki until 1977. That’s when Yamaha launched its XS11. Kawasaki’s flagship, which had now evolved into the KZ1000 and then the Z1-R, lost a comparison test, scoring second to the new kid. Later that year, Honda launched its now-iconic CBX and its weird inline six-cylinder engine. Practically overnight, the Kawasaki Z fell to third place. Then, in 1978, Suzuki launched its GS1000, delivering another blow to the Z and placing it in a distant fourth place.

The Z1-R separated itself from the KZ1000 with cafe racer-style bodywork and a slightly hotter engine claimed to make 90 HP, seven ponies more than a KZ1000. Cycle magazine reports that while Kawasaki said that the Z1-R made 90 HP, its actual output was about 70 HP at the rear wheel, or not much off from a regular KZ1000. But worse than that was the frame. While Kawasaki added extra gussets, the frame still had the rigidity of a wet noodle, which meant that its handling was subpar. At least the brakes were now three meaty discs. Either way, the Z1-R wasn’t a hot seller, and motorcycle magazines largely agreed that Kawasaki was no longer the king.

Boosting Back On Top

As luck would have it, a solution was already in the works, sort of. In 1977, the American distributor for Kawasaki began exploring turbocharging the Z1-R, but this was ultimately shelved. But Allen Masek, then a Kawasaki executive for 11 years, decided to revive the turbo Z project. Masek believed in the original turbo project so much that, when he left Kawasaki, he made it his mission to bring the turbo Z to life through his company, Turbo Cycle Corporation.

Masek wasn’t sailing in entirely uncharted waters. By that point, turbocharging had been of interest to the motorcycle aftermarket world, and if you were crazy enough, you could order a turbo kit from American Turbo Pak, Inc. (ATP) that boosted your BMW, Honda, Kawasaki, or Suzuki. Turbo kits were so alluring, even, that between 1975 and 1978, ATP sold more than 2,000 motorcycle turbo kits.

But nobody was ballsy enough to sell a turbocharged bike right from the dealership floor. That’s where Masek came in. Masek partnered up with Rajay Industries, Inc. to make his bike’s turbo. The firm had experience making turbos for cars, boats, planes, and diesel engines. He also pinched ATP for the turbo’s plumbing and hardware, and his own company, Turbo Cycle Corp., to put it all together. The completed motorcycle would be sold out of Kawasaki dealerships. These weren’t true “production” motorcycles, as Turbo Cycle took existing bikes and souped them up, but they were the first that you could buy brand new off the dealership floor.

Here’s what you got when you bought a Kawasaki Z1-R TC in 1978: The base bike was a Kawasaki Z1-R, which wasn’t too hard to obtain due to the model’s slow sales and unsold units sitting in dealers. Turbo Cycle would install header pipes with a new cylindrical exhaust collector. These new pipes fed the Rajay turbo, which in turn pressurized the fuel and air mixture coming from the 38mm Bendix accelerator-pump carburetor and fuel pump. Boost control was handled through an adjustable wastegate.

More Quirks Than Features

Unlike the Honda CX500 Turbo, the Z1-R TC was not particularly high tech. It did not have an ECU or fuel injection. The Z1-R TC also did not have a rev limiter. If you opened the throttle wide open and left it there, the turbo would just make the engine rev higher and higher until it floats the valves and breaks apart.

There were other quirks, too. The wastegate was easily adjusted by the end user. The turbo was initially limited to 10 pounds of boost, but later, Turbo Cycle brought the boost down to 6 pounds for better reliability. Then, the company recommended setting the turbo to no higher than 8 PSI. However, there was really nothing stopping you from really cranking up the boost. If you were crazy enough to disobey Turbo Cycle’s recommendations, the company said that you should at least reinforce the engine’s internals. Yes, this meant that, if you were not careful, there was more than one way to blow up a Z1-R TC. Either you could rev it out of control, or turn the boost up way too high.

A Kawasaki Z1-R TC made anywhere between 105 HP and 130 HP, depending on your bike’s exact configuration. In adding the turbo kit, your quarter mile would drop from about 11.95 seconds to 10.85 seconds with a speed increase of 110.25 mph to 130.62 mph. It also weighed only 565 pounds, or not much heavier than a stock Z1-R. In other words, the Z1-R TC had enough performance gains to allow it to reclaim the title of “the king.”

Turbo Cycle also found a clever way to sell the Z1-R TC. Kawasaki never gave the Turbo Cycle project its blessing. So, your bike did not come with a warranty. According to Motorcycle Classics, buyers were required to sign a form that acknowledged that they would not have a warranty for their basket case turbo motorcycle. But even more than that, buyers also had to sign a liability waiver.

While Kawasaki was okay with selling these things out of its dealerships, it wanted nothing to do with what could happen if one of these bikes went all pear-shaped. Clearly, Turbo Cycle didn’t want to deal with legal trouble, either.

All of this came on top of paying $5,000 for the motorcycle to begin with. To be fair, $3,695 of that was for the donor Z1-R, but it still wasn’t cheap. According to Cycle magazine, Turbo Cycle’s plan was to sell these things for about the same price that it would cost you to buy a new motorcycle, buy a turbo kit, and then have a professional install it. The only problem with this pricing strategy was that you could buy a Kawasaki KZ1000, buy a turbo kit, and install it yourself for less than $4,000 total.

Pricing wouldn’t be the only problem with the Z1-R TC. One major issue was that the turbo didn’t really spool up until about 4,500 RPM, and peak boost wasn’t made until around 7,000 RPM, right before you had to shift at 8,500 RPM. This meant that there was a high boost threshold, or the point at which there was enough exhaust to spin the compressor. It also meant that, at low RPM when it wasn’t in boost, the Z1-R TC was also slightly slower than a naturally aspirated Z1-R due to the exhaust restriction. So, you had to ride the Z1-R TC hard to get the performance the turbo promised.

What’s also wild is that, per Cycle magazine, the completed bikes technically didn’t have all of the parts that you needed to go fast:

While the turbo kit has been bolted on neatly enough, there are tasks which the thorough Z1-R TC owner should consider. If he plans to ride especially hard or to race, certain crank pins should be welded in place to prevent the crankshaft from twisting.

The Banzai rider should give thought to modifying the Z’s pan to assure that a sufficient amount of oil stays in proximity to the oil pick-up. Seriously consider adding high-quality aftermarket valve and clutch springs.

Although for turbocharged bikes ATP recommends “the best quality suspension components” in its standard brochure, the Z1-R TC does not come that way. As with the crank welding, pan modifying and spring upgrading, a rider who plans to use the Z1-R TC to its maximum should upgrade at least the rear shocks.

Yes, this meant that a Z1-R TC buyer got a bike with a suspension that was technically too weak for the power, and they were more or less told to fix it themselves. The bikes the public bought were also slightly different than what the press got to ride. The press bikes had welded cranks, 36 degrees of spark advance, and race gas in their tanks.

The Z1-R TC Was Stupid Fast

Yet, the Z1-R TC was a mixed bag for motorcycle reviewers. From Motorcycle Classics:

[P]eriod testers, including Cycle Guide’s team, found the TC to be pretty ornery to live with. It was difficult to start from cold, requiring a long warm-up, and then ran roughly unless given regular open throttle runs to “clear its throat.” It also seems the turbocharger selected for the TC was larger than ideal, meaning it was slow to respond, resulting in significant “turbo lag” before delivering its performance in a rush that required a close watch on the tachometer. Maneuvers like overtaking required careful planning, so testers would open the throttle and hold the bike back on the brakes until a passing opportunity arose.

Cycle Guide also found that their TC smoked on the overrun and needed additional oil every few hundred miles. But adding oil wasn’t easy, as the turbo’s oil return screwed into the oil filler, requiring tools to remove the return just to add oil. Worse, the Z1-R’s on-board tool kit was missing, its allocated space filled by the Bendix carb’s electric fuel pump! Other niggles included an easily defeated alarm system — and the fact that the turbo kit’s fasteners were SAE sizes while the rest of the bike was metric.

So the TC might not have been ready for prime time on the street, but it certainly performed on the strip, delivering sub-11-second quarter-miles at 125mph-plus — until the clutch expired, anyway. Cycle Guide was even more impressed with the TC’s open road performance boost: “Nothing comes close to the out-of-the-slingshot sensation you get when the boost comes up near the 10 pound maximum,” they said, noting at the same time that the TC probably approached the limit for the tire technology of the day.

Cycle magazine had an interesting perspective:

What’s the TC like to ride? We’ve had experience with any number of hard-accelerating vehicles: Superbike Production racers, Suzuki RG500 square fours, Yamaha TZ350s, factory-built snowmobile racers, Harley-Davidson Top Fuel dragsters. The street TC Kawasaki accelerates harder than all of these except the Top Fueler. Engine speed must be high when leaving the line, and the throttle must be open for the boost to be up; get all that organized properly and the TC will yank you down the strip like nothing else you’ve ever ridden. But the trip back up the return road is almost as astonishing: ridden moderately, the TC feels, sounds and acts a lot like a box stocker.

That sounds like the best of both worlds. Under most conditions the bike has the moderate manners it was born with; ask it to produce power and it will produce more than anything else on the street-more, under most circumstances, than you can ever hope to use.

If the TC concept is flawed in any general way, it is the substantial hole at the center of the bike’s performance character. At one end of the spectrum it runs like a stocker. It idles, doesn’t overheat, gets over 40 mpg and doesn’t make very much noise. At the other end of the spесtrum it goes so damn fast that it is at best impractical and at worst unbearable. There does not appear to be much middle ground here, middle ground being defined as a transition envelope wherein the bike produces power output that is pleasantly more robust than stock without being terrifying. The TC Kawasaki is like a switchblade: open or closed. Its performance can be adjusted by loosening up the preload on the waste gate to reduce maximum boost, but the TC’s rather snappish upper-end character remains as an inescapable legacy of the turbocharger and all the ducting that goes with it.

Ultimately, the Kawasaki Z1-R TC was a bit of a motorcycle misfit. Racers and tuners loved riding them at the limit, but the general public didn’t really scoop up many of them.

Around 250 units were sold in 1978, and another were sold in 1979. The 1979 models were actually 1978 models with new paint from California design house Molly Designs, a 4-into-1 collector for less turbo lag, an oil pan baffle, a new fuel pump, a relocated oil return line, and the turbo brought down to 6 PSI. There were other small changes, but the 1979s were still largely similar to the 1978 models.

A Short-Lived Future

While the Z1-R TC experiment may not have been a hit, it would become only the first in a short-lived fad to turbocharge motorcycles. After Japan gave up on trying to make turbo motorcycles a thing, the concept would fall back into obscurity. Even today, the most famous motorcycle with forced induction, the Kawasaki Ninja H2, uses a supercharger. Honda’s newest engine, the V3R 900 E-Compressor, is also boosted, but it uses an electric compressor rather than a turbo or a supercharger.

In theory, a turbo bike might work today if the turbocharger is of a variable geometry flavor, and the engine’s compression is high enough. However, turbocharging a motorcycle still adds expensive parts, complexity, and weight. For most bike builders, it’s just easier, cheaper, and simpler to just build an appropriate naturally aspirated engine.

So, turbo bikes will always be oddballs. These motorcycles were more complex, more expensive, and more or less worked like a light switch. Either you went no faster than stock, or the boost kicked in and you felt like you got kicked by a horse. Forget about a middle ground. Still, it’s fascinating that several companies at least gave it a try. At least for a short few years, some people clearly thought the future of motorcycles involved turbos, and that’s wild.

(Update: Clarified that the motorcycle had a high threshold, not specifically turbo lag.)

Top graphic image: Bonhams

Where does Ms. Streeter get the energy to generate so much solid content? She’s the Z1-R TC of auto journalism! Don’t over-rev: We want many more years of reliable service. 😉 – Rob

I’ve wondered about the same thing. She’s a great writer and somehow always finds time to write high quality articles for us.

Those were great days in motorcycle history. In 1978 I was 17 years old. All I cared about was racing motocross. I never even thought about street bikes. You young guys should understand, these bikes, the big 4 cylinder, 4 strokes, they were such a big deal that I remember buying a street bike magazine to read about them. The 70’s and 80’s were exciting no matter what type of riding you did. I started racing on a 1975 Honda XR75, then my sponsor put me on the 1976 Honda 125cc Elsinore. The following year, we were riding the new Yamaha YZF 125cc., I mention these bikes, not to boast, but to say, each one was legendary for it’s time, much like the street bikes in this article.

I’m about four years older than you, but I remember the Elsinores. I only rode dirt bikes a couple of times but wish I had started out on them as when the front or back end of street bike started sliding, it was terrifying. My first bike was a 1980 4-cylinder Suzuki GS 550. It wasn’t the fastest in its class, but it was the largest and a better fit for 6’2″ me. And it was plenty fast. I saw 110 mph, and it still had more.

First turbocharged bikes sold – technically, Godier Genoud, but I’ll allow it 😛

I believe they were complete well thought packages though, engine internals, frames and whatnot.

They had a yummy six cylinder turbo as well, later.

Z1300-based, just bored to 1411cc, and then add turbo, because why not.

This still looks less frightening than a Kawasaki H2 750cc 2 stroke. I have seen and heard a BMW R100RS with a Luftmeister turbo kit and Krauser 4 valve heads, which cost almost as much as an R100. Knowing what I do I wonder how many times it broke before it got reliable.

I’m not sure I understand. They didn’t change the heads or compression, so why would it make less power than stock?

Maybe turbo backpressure or tuning adjustments?

So far as I’ve read in old magazine tests, this was because of the exhaust restriction when you were not in boost. It wasn’t much of a difference, but I guess enough for some mags to note.

Bikes are extremely sensitive to exhaust design, even without a turbo.

The X pipe design was derived from bike tuning.

I’ve never seen or heard of these. Thanks for the article Mercedes.

A friend had a Gpz 750 Turbo which handled decently but had a 2 stroke light switch throttle. Far worse in terms of too much power with a light switch throttle was another friends H2 750. He had a set of aftermarket pipes on the thing and had done a bunch of work on the chassis and engine. Pure evil. After rides on each I stayed with my Suzuki Katana 1000 which was plenty fast but didn’t try to knife you while you rode it.

No, It had a high boost threshold, Not the same thing as lag.

Please explain.

Spool up at 4,500 = high boost threshold?

4,500 to 7,500 for max boost = turbo lag?

Boost threshold is the place in the rev range where there’s enough exhaust to spin up the turbo. Below the boost threshold the engine works like an N/A vehicle with an exhaust restriction.

Turbo lag is the delay between the accelerator being pressed (or twisted) and the power arriving – the turbo needs the exhaust gas to spin it up so it takes a moment. In the old days that moment could be two seconds. Turbo lag is the reason Senna used to drive the way he did:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JUVkVB3SUf4

Even though the NSX is N/A he drove it the way he drove the turbo F1 cars – prodding the accelerator like that would provide smooth and modulated power for a car with massive turbo lag.

Good enough for me. I have issued a correction. Thank you for the education!

Better than I would have tried to explain it, Thanks 🙂

Presumably an engine with a high boost threshold would also have high turbo lag?

I believe so – turbo lag is a function of the length of the intake tubing between the turbo and the motor too, but overcoming the inertia of a hefty turbo is always problematic.

Fun video clip to watch.

No wonder his nickname was hp!

A million years ago, back in the late 80’s, I very nearly got one of these.

AS MY FIRST BIKE TO RIDE as a newly licensed rider.

Up to that point, I had learned on a Honda MB5, a 50cc, two stroke street bike. When I got my M endorsement at 16, my Dad went shopping for something for us to share.

But it was mostly going to be my daily rider to school and work while we fixed up the ’60 El Camino he’d bought me as a project for my first car.

So, Dad had a thing for oddball contraptions. He’s the guy who bought the Triumph Spitfire project with a Mazda RX-7 drivetrain swapped in that nearly burned down our garage. He’s also the guy who built the 30hp attack canoe (aluminum canoe with a transom added and a 30hp outboard bolted on).

So when he saw an ad in the local paper for “1978 Kawasaki turbo motorcycle. Lots of fun to ride. Must sell.” he was understandably intrigued.

He went to look at it, and it seemed to be in decent shape. He test rode it, and while it had a LOT of power, it didn’t seem too crazy.

He and the seller went into his workshop to maybe make a deal. As they walked in, Dad saw a framed picture hanging on the wall. It was a photo of the bike being ridden (presumably by the current owner) in a wheelie through the traps at the local drag strip with a 10 second timeslip taped to the glass.

I ended up with a KZ 440 instead.

My uncle nearly bought one of these new as well. I don’t recall what class he raced in, but he was a fairly competent amateur motorcycle racer and felt he could handle the bike. As he relates the story, he took the bike for a test ride and realized it was way too much power for the chassis, returned it and ended up with something else. He actually ended up with the tank from the bike as a keepsake, as the person that bought the bike immediately wrecked it and parted out the remnants.

Oh, and no shame in the KZ440. My best friend from high school had an ’82 KZ440 and it was, and still is decades later, a sweet riding bike. Definitely a classic in my eyes.

My ’80 GS550 was also sweet, and I never had to touch its carbs. It was a long time ago, but as I recall, the only really weak thing on those was the alternator stator. If you let the battery get too old or rundown, they would fail.

The KZ440 was a much wiser choice. The Mikuni carbs would hold a steady idle,unlike the Keihin carbs on the KZ400 that was my first bike.

That photo of the Z1R and 930 together is making the late ’70’s preteen that lives perpetually inside of me all giddy and warm.

For all of the inherent “flaws” that the modern world will point out today, back then, (you had to be there, kids) those were considered absolute state-of-the-art dream machines and still immensely iconic today.

Sigh… 🙂

My first bike was a 1974 Kawasaki 500 2 stroke triple my dad gave me . I am glad it never ran well enough for me to end myself in a accident. 70s bikes were scary AF with the loads of power and crappy tires, brakes, suspension.

But so, so much character and fun! (I still have my ’75 H1 500).

Yes, I sold it to a buddy who got it running right and he drove it to my wedding were all my uncles and cousins were pointing out which dents and scratches were theirs.

Awesome!

I’d love to see what could be done with retrofitting one of these bikes with modern turbo tech.

Garrett these days, with their G series turbos, are supporting triple digit HP increases over an equivalently sized unit from even 10-15 years ago.