I always thought claims we are now living in a post-truth media age were slightly alarmist. Surely anyone with a modicum of curiosity and intelligence has the wherewithal to double-check their facts and sources before opening their pie-hole or committing their unhinged takes to the digital airwaves? At the very least, I thought our little car enthusiast corner of the world was immune from such speak first, think later bullshit, but something happened recently that had me genuinely questioning this assumption.

I was at an informal gathering of car design industry locals, listening to the guest speaker who was an extremely well-known car designer. I was about three beers in by the end of his talk and my eyes were starting to glaze over, when suddenly he said something about another extremely well-known car designer he had worked with that made my ears prick up. I asked the guest speaker to repeat what he said to make sure I had heard correctly, and indeed I had. My reply to this revelation was “well [redacted] is just another chancer like Colin Chapman, in that case.” In the audience at the back of the room, yet another well known car designer loudly exclaimed in my direction, “You cannot talk about legends of the industry like that, I don’t have to listen to this!” and proceeded to flounce out of the event in front of about thirty of so fellow professionals.

Afterward, the young designer who organized the event door stepped me and did a very polite, “Who the fuck do you think you are, that’s just your opinion of Chapman.” I told him who I was, what I did, and to go and read a fucking book or two. The exact nature of what was revealed, who said what and who all the players are is not for public consumption (so don’t bug me in the comments about it), but what really shocked me was that the young designer thought I was just stating an opinion about Colin Chapman, when it’s a widely acknowledged fact he dodged going to jail for massive fraud of the British taxpayer by inconsiderately dying of a heart attack in 1982. If the generation of industry professionals coming up behind me doesn’t have a grip of the truth and are going to dismiss inconvenient facts as opinion, then what hope is there?

We’re All Being Lobotomized

Anyway, the point of all this is not to brag about my ineffable ability to put noses out of joint but to highlight how quickly stories and context can be forgotten in the fast-moving, bite-sized, hot-take modern media age, where people get all their knowledge from the internet. Often when I’m thinking about articles, I assume certain things about cars, car culture, and history are common knowledge – the table stakes for holding an enthusiast card. No one is going to be interested in me writing about X because surely that story is already well-known. But increasingly, I’m finding that is not the case, and misinformation and false narratives are just as pervasive in the automotive sphere as they are everywhere else. A designer friend recently said to me, “There’s no sacred cow you won’t hold a knife to, is there?” So, at the risk of looking like Peter Finch in the film Network or Judd Hirsch in the Studio 60 pilot (ask your parents), I again have a sharp utensil in my hand and another idolized car with a fallacious narrative to skewer: the 1991 Le Mans winning Mazda 787B.

Author’s note: This is another special edition of Damn Good Design. It had been my intention to have it done for the holidays, but as some of you will have noticed, I’ve been slightly absent recently. That’s because I was waylaid with a viral infection that inflated the glands in my neck to the size of baseballs, rendering me incapable of doing much of anything. It took two courses of antibiotics and consuming my own body weight in Paracetamol (Tylenol) for about three weeks to recover.

Further impeding speedy delivery was a bit of complication: throughout the late eighties and early nineties, FISA-sanctioned sports car racing had a variety of different names, but they all referred to the same series. According to the dreaded Wikipedia, they are as follows:

1982–1985: World Endurance Championship

1986–1990: World Sports Prototype Championship

1991–1992: Sportscar World Championship

Doing this story justice meant a much longer article and a lot more research than I originally planned for. So consider this a late New Year’s present, so you can all start 2026 as irritated as me. Enjoy.

Ah yes, the 787B.

The plucky underdog that beat the combined might of the Porsche, Mercedes, Jaguar and Peugeot works teams. The racer that was unfairly penalized at the 1991 running of Le Mans by being relegated to a lowly grid position. The car that raced despite the fact it was technically illegal. And finally, a car so fast it was banned from Group C racing by FISA to protect the interests of said European teams. That 787B right? Wrong. None of these oft-repeated narratives have even a telephone relationship with the truth. To coin a colloquialism, it’s all a load of complete bollocks.

That the 787B is an iconic racing car is beyond doubt – that Le Mans win in 1991 was the first and only win for a Japanese manufacturer until Toyota mopped up five consecutive victories at the end of the LMP1 era from 2018 to 2022. A remarkable achievement but like all legends inconvenienced by the truth and circumstances that led to it. The bottom line is the 787B wasn’t really that fast compared to the rest of the Group C field that year, and outside the 24 hours wasn’t competitive at all. June 1991 aside, why does the 787B have such a hold over a certain deluded section of the enthusiast community? Four words: Rotary engine and Gran Turismo.

The 787B has been present in every Gran Turismo release since GT3: A-Spec in 2001. The impact of the seminal racing game on the wider enthusiast scene is worth an essay of its own, but there’s no doubt certain cars have had their real-life status elevated by being included in the series. It’s fair to say that, compared to other Group C racers in the latest entry GT7, the 787B is ridiculously overcompetitive. Nonetheless, for a lot of people, Gran Turismo is their first exposure to cars they may not have heard of or may have never seen in real life (I have seen and heard the 787B at Le Mans Classic, and it is LOUD).

The Rotary Engine Obsession

Why was Mazda so committed to the Wankel engine? The limitations of the configuration were well known way before the early nineties. Mazda had made the rotary a core part of their identity since the introduction of the sporty Cosmo 110S of 1967. The sprightly performance of the lightweight coupe convinced Mazda that rotary power was the future: they hoped it would give them a technological edge over their larger domestic rivals. With its ability to pass Japan’s stringent emissions tests, Mazda became so convinced of the rotary’s benefits as a powerplant they proceeded to install it a series of vehicles it was entirely unsuited for, including the luxury Parkway 26 minibus of 1972 and the Holden HJ based Roadpacer – both prime candidates for my “how the fuck does that thing move?” file alongside the BMW E34 518i, Euro MkII Ford Granada diesel and anything with an Iron Duke four ‘powering’ it.

While the qualities that made the rotary perfect for a lightweight sports car (compact dimensions, low mass, high revving, smooth power), its demerits which included lack of torque and horrendous fuel economy made it less capable of more prosaic duties like being fitted to a bus or a large, heavy luxury sedan. Indeed, the rotary-powered Parkway 26 minibus was so underpowered that it needed a separate combustion engine to run the air conditioning. But the rotary was at home in a different arena where those drawbacks didn’t matter so much: motor racing.

When it comes to the rotary, the 787B represents the apex (ha!) of a decades-long effort to prove the worth of the unorthodox engine to the wider motoring world in the scalding hot crucible of competition motorsport. This is where the first of those 787B myths gets busted. The 787B was created, built, and run by Mazdaspeed, a full works factory team. They were not underdogs – they were lushly financed, populated by top engineers and, by 1991, a well-drilled outfit with a lot of high-level motorsport experience. If anything, Jaguar were the relative underdogs of the piece: a scrappy outfit run on a comparative shoestring by all-round wide boy Tom Walkinshaw. According to the Sportscar World Championship roundup in the 1991 edition of Autocourse, Adam Cooper of Autosport magazine writes:

TWR ran on a fraction of the budget of the main opposition, and did virtually no development, although there was an upgraded engine at mid-season. When Peugeot’s big spending paid off and the French team caught up, TWR was nearly caught out.

The Long Road To Le Mans Began In 1968

Mazda’s motorsports program began in earnest in 1968 with the racing debut of the Cosmo 110 at the 84 hours of Nürburgring, a time trial originally held on public roads as the Liege -Rome – Liege event. When that rally got too dangerous for public roads, it transitioned to the infamous Green Hell to make sure it remained a challenging endurance test of driver and machine. Mazda rotary chief engineer Kenichi Yamamoto directed developments to the Cosmo’s twin rotor 10A to up the power from a stock 110 bhp to 130 bhp. Mazda roped in famous Japanese hot shoe Nobuo Koga to head up piloting duties along with Yoshimi Katayama and Masami Katakura, for all Japanese lineup in car #18. The second #19 car was driven by a trio of Belgians: Jean Pierre Ackermans, Yves Deprez, and the unfortunately named Leon Last. Backed up by a JAL DC-8 full of spares and with Japanese pride on the line, the #18 car crashed out after a rear axle failure, but the Belgians hung on to finish a credible fourth. Encouraged by this decent showing, Mazda was convinced endurance racing would be the perfect showcase for demonstrating the reliability and power of the rotary engine, and they set their sights on the most famous long-distance race of them all – Le Mans.

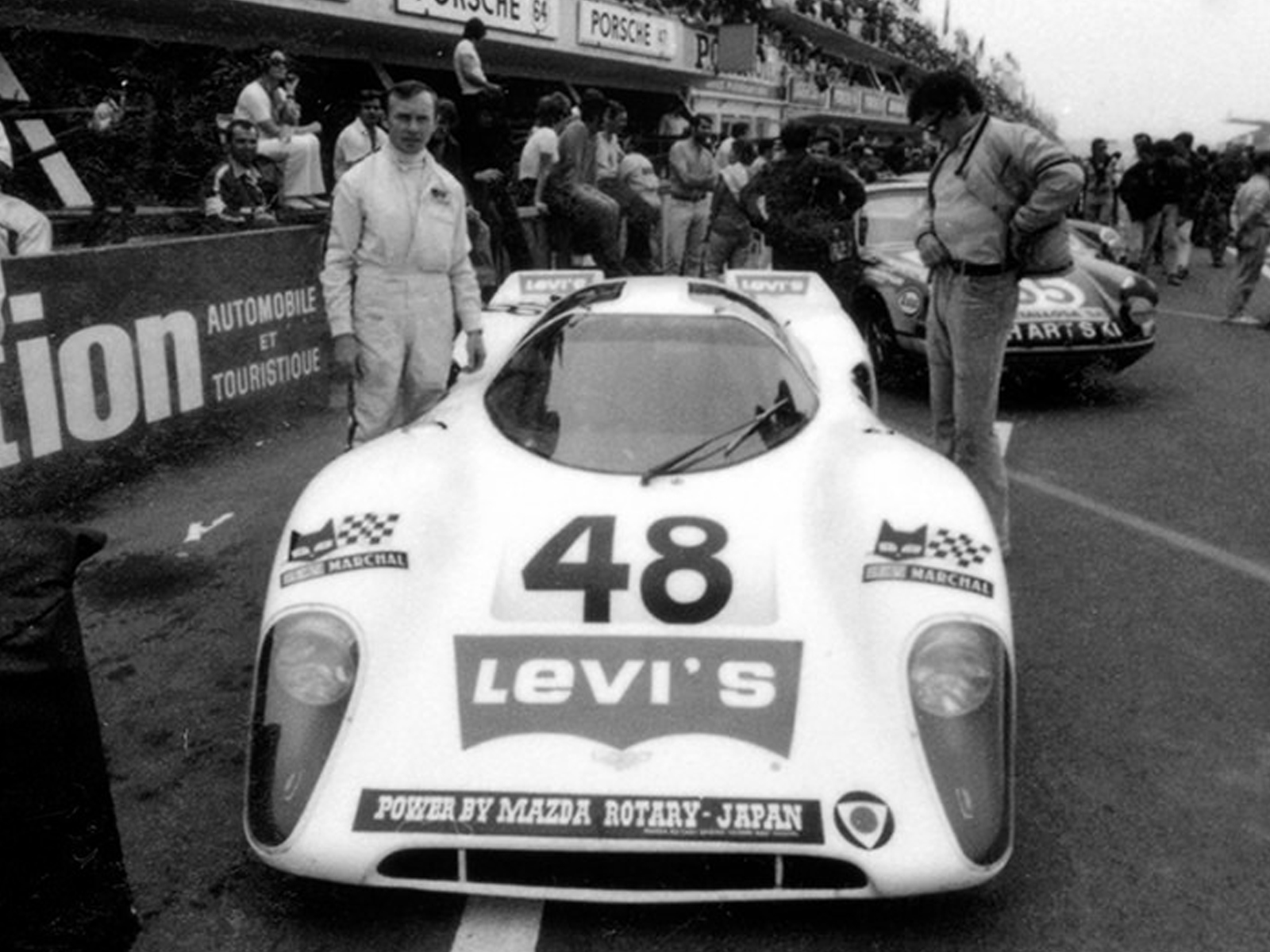

Their first appearance at Le Sarthe was low-key. In 1970, Yves Deprez used his Mazda connection to bolt the 10A into the back of his privately entered Chevron B16 in place of the usual BMW 2002 engine or Cosworth FVC. Mazda had never put the rotary engine in the middle of a race car before, so they were not sure how it would respond to having a much shorter exhaust system. As a result, the B16 Mazda had a long and torturous tailpipe arrangement. The car lasted all of 19 laps before the engine failed.

After the 1970 Le Mans race, the domestic racing team Mazda Sports Corner centered their initial racing efforts around turning the newly launched 1971 RX-3 into a competitive touring car. Competing in domestic races eventually culminated in a fierce on-track rivalry with the Hakosuka Skyline GT-R. Within a few years, the RX-3 was winning in the US, the UK, and Australia. But for Mazda Sports Corner manager Takayoshi Ohashi, the real goal remained Le Mans.

1991 Began in 1973

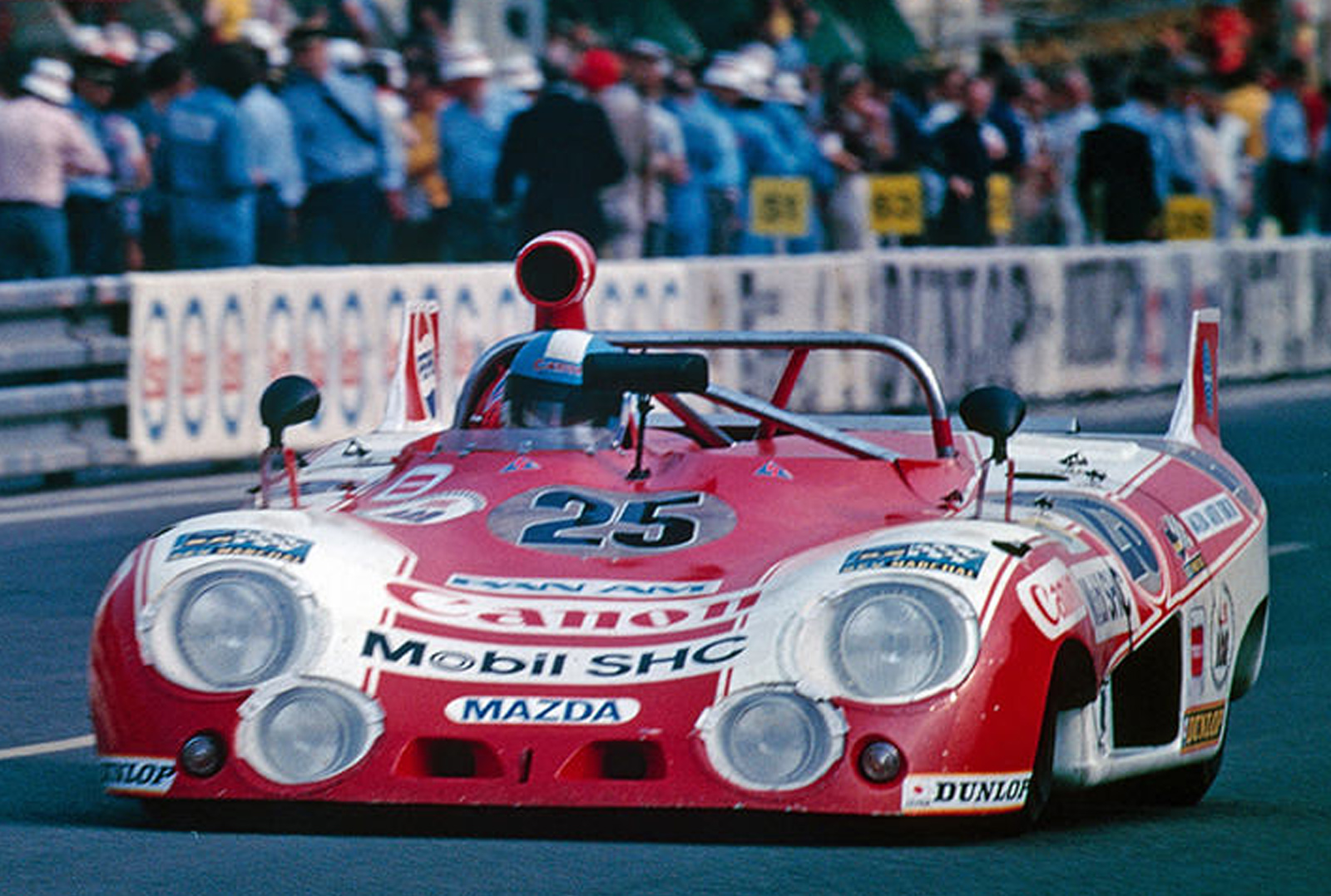

In 1973, Mazda partnered with the newly formed Sigma Automotive team (what is now SARD Racing) to run a purpose-built 12A-powered MC73, the first time an all-Japanese team entered Le Mans. They managed a grand total of 79 laps before the gearbox called time. Undeterred, they tried again in 1974, marking the debut of “Mr. Le Mans” Yojiro Terada (who would race in the 24 hours 29 times). This time, they managed to successfully complete the full race, albeit with a final finishing position of stone-cold last. Both the MC73 and MC74 were professionally stunted little sports cars with stubby bodywork and haphazardly slapped-on sponsorship decals. They were never going to cut the French mustard against battle-hardened veterans like Matra, Ferrari, and Porsche, so Mazda performed a tactical withdrawal to perform further development and temporarily alter their approach.

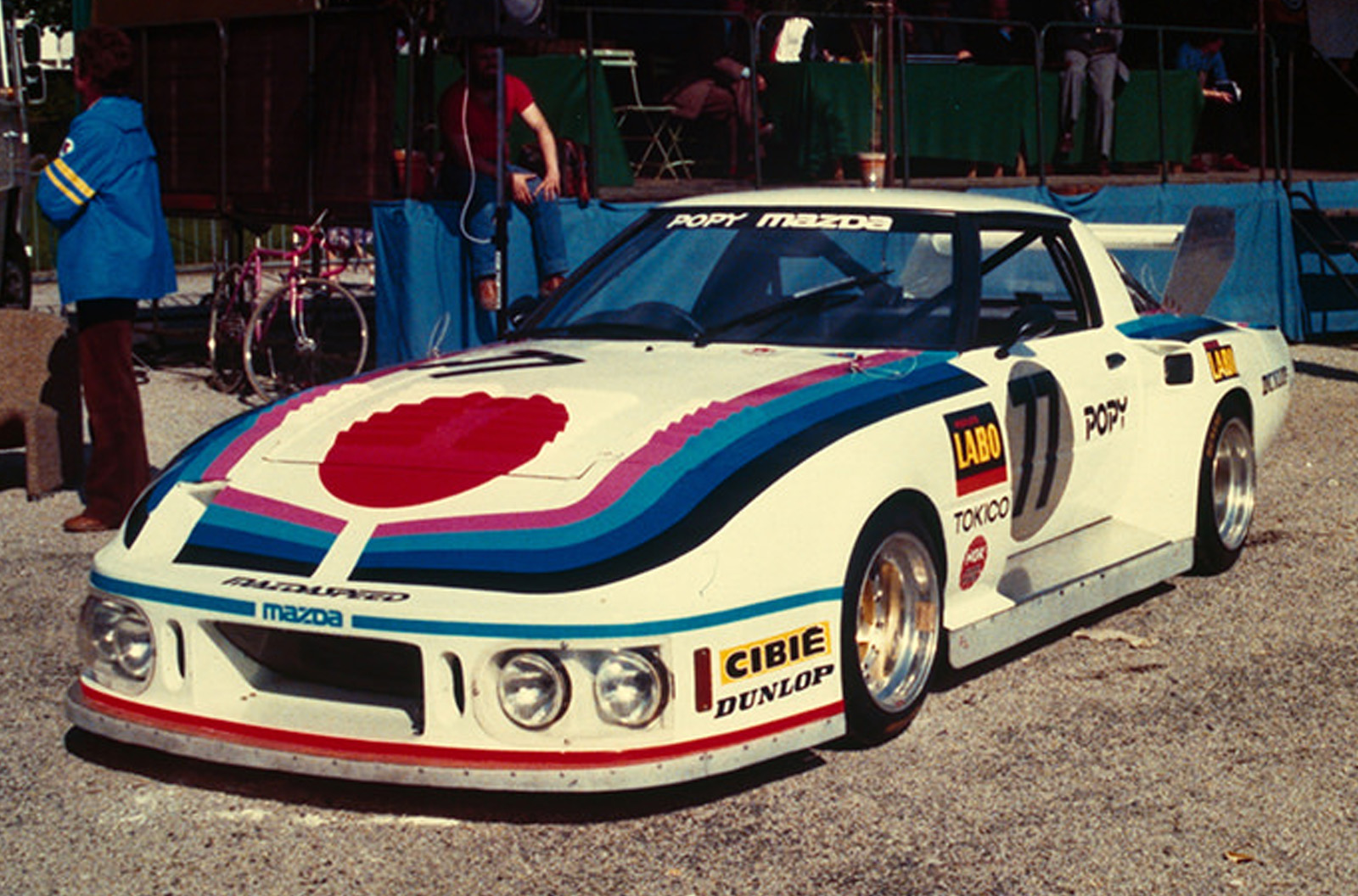

When Mazda returned in 1979, it was not with another sports prototype but an RX-7-based racer: the 13B powered 252i. It failed to qualify by less than a second, so Ohashi turned to Tom Walkinshaw, who was campaigning RX-7s in the UK. More pertinently, a TWR RX-7 had won the 24 hours of Spa in 1981, another first for a Japanese manufacturer. After sitting out the 1980 Le Mans, TWR entered an IMSA class RX-7 253i in 1981, only for it to retire after four hours and 25 laps with transmission failure. The next year, the TWR 254i retired 18 hours into the race with an engine failure. But 1982 was important for another reason: it marked the advent of Group C.

The Arrival of Group C

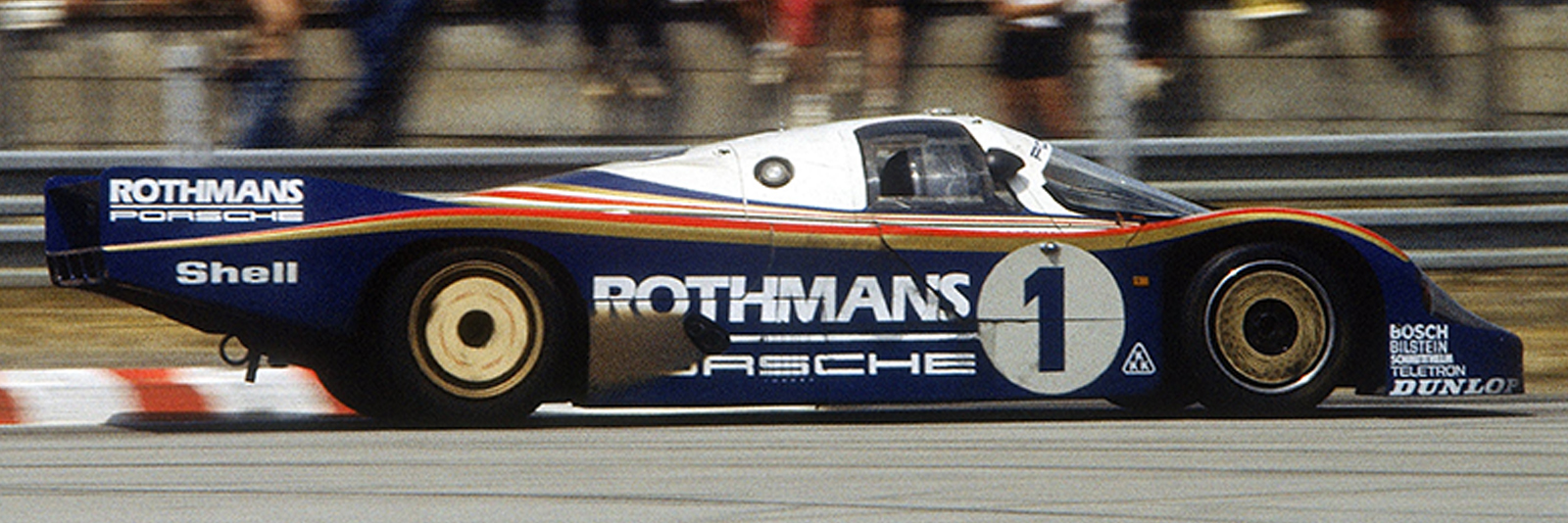

The intervening years had seen the regulations for sports car racing in a state of flux. By introducing Group C, FISA intended to rationalize the disparate classes that competed in sports car racing. Le Mans had always been (and remains) organized and administered by the Automobile Club de l ’Ouest (ACO) – not FISA, so was immune from the political machinations of President Jean Marie Balestre, who wanted control of the race. Because the 1982 Le Mans was the first to be run under Group C regulations, older Group 5 and 6 as well as IMSA GTX cars were allowed to take part, ostensibly to bolster the field. The reality was a new era was dawning. The new Porsche 956 took all three podium positions, and the Mazda 241i could only manage 170 mph on the Mulsanne compared to 221 mph for the 956. The following year, there would be no grandfathering of the old classes – Le Mans would align with the FISA World Endurance Championship and become an all Group C race.

The idea behind Group C was to create a fuel efficiency formula, with the cars limited to 100 liter (26.4 US gallons) fuel tanks and a minimum weight of 800 kg (1764 lbs.). The only requirement for engines was that you had to have built a car for another FISA-sanctioned series. In other words, you had to be recognized racers. Once that requirement was fulfilled, cylinder count, aspiration, and capacity were all open. With all the non-Le Mans races in the championship being contested over 1000 kms (621 miles) and a maximum of five stops permitted, Group C cars would effectively have to cover the shorter race distance with 600 liters (158 US gallons) – roughly 4 mpg.

The Porsche 956 was created by yoinking the 2.65-liter twin turbo air-cooled flat six (an aborted IndyCar engine) out of the 936/81 and bolting it into the back of a new ground effect monocoque. Ford had the hopeless C100 and Lancia had the Ferrari-powered LC2. As it was governed by the ACO, not FISA, competing in the full World Endurance Championship was not necessary for Le Mans entry, so the 24 hours attracted a variety of smaller teams – including French local heroes Rondeau and Welter Racing (backed by Peugeot), Japanese outfit Dome (of Dome Zero fame), Lola, and countless others. It was a right mixed bag of full factory efforts, one-off no-hopers, and Le Mans specialists.

Presciently recognizing that costs might get out of control in the future, in 1983 FISA introduced a junior C2 class with a fuel limit of 55 liters (14.5 US gallons) and a weight limit of 700 kg (1543 lbs.). This is the class where Mazda first set its sights with a purpose-built Group C car: the 717C. This spud-ugly racer had a small front area and low drag bodywork. With 956 customer cars now available, the Porsches dominated the race, taking 9 of the top 10 places – but the diminutive Mazda managed to win the C2 class, finishing twelfth overall. According to Inside Mazda:

“Having entered RX-7s at Le Mans from 1979 to 1982, the new for 1983 Group C regulations allowed Mazda to build its first full sports prototype racer. Entered in the smaller Group C Junior class, the diminutive 717C was powered by a twin-rotor engine and had an aluminium monocoque chassis. Its sweepy low drag bodywork and enveloped rear wheels were designed to ensure the highest possible speed along the famous Mulsanne straight, but with very little downforce and a short wheelbase – the little Mazda was a handful for the drivers.

However, its speed and endurance resulted in a 12th place finish overall and the Group C Junior win. In fact as a mark of the Mazda’s reliability – the only other finisher in the Group C Junior class was the second 717C of British drivers Steve Soper, James Weaver and Jeff Allam, who took the flag in 18th overall”.

For the 1984 race, team Mazda hedged their bets: they upgraded the 717C to become the 727C and, as a second line of attack, supplied an American privateer with 13B rotaries for his pair of Lola T-616s for a total of four Mazda-powered cars. The Lolas took first and second in C2, with the works 727C finishing fourth. This car was upgraded again for 1985 to become the 737C, which this year raced in the entire WEC. At Le Mans, they managed third place in C2.

Mazda Again Turns To a British Person For Help

The 737C was by now uncompetitive, and by 1986, Group C was getting very serious indeed. The Porsche stranglehold on endurance racing was faltering with Jaguar and Sauber (later to become the works Mercedes entry) nipping at Porsche’s ankles. In addition, two other big Japanese OEMs were taking part: Toyota through the works-backed TOMS team (Honda were balls deep in Formula 1), and Nissan. Clearly, Mazda’s engineers would have to build a proper, grown Group C car. To assist them, they employed the services of experienced British racing car designer Nigel Stroud, who had previously worked on the innovative but banned twin tub Lotus 88, the first F1 car to use a carbon fiber monocoque. The resulting 757C (747 was skipped for obvious reasons) used a new three-rotor 13G engine. Although the 757C competed in the Japanese Sportscar Championship that year, Le Mans places much harder demands on a race car and both 757Cs retired with gearbox problems. But in 1987, the car did manage a seventh-place finish.

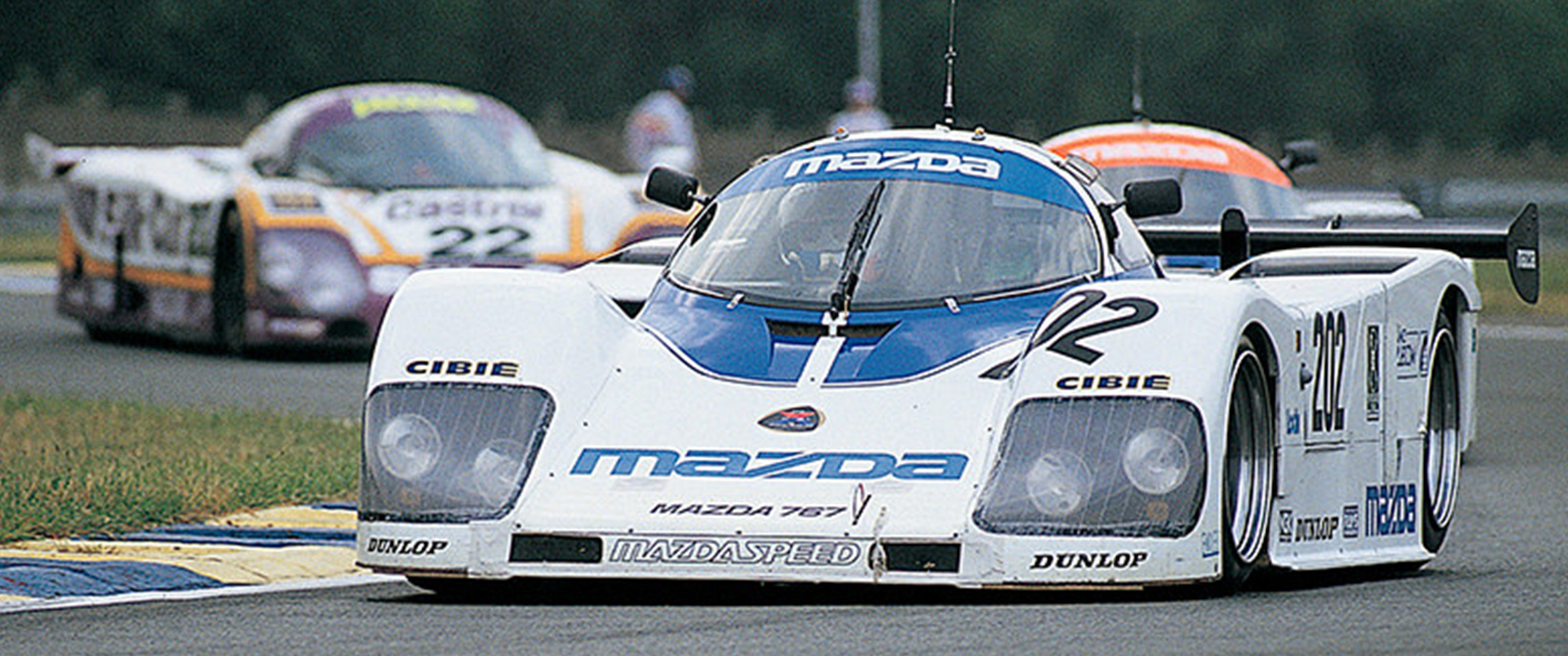

In 1988, Mazda introduced the 767 with a four-rotor 13J. It was a rush job created by simply bolting an additional rotor housing onto the existing three. It was long, heavy, and underdeveloped, resulting in 17th and 19th place at that year’s Le Mans. They also entered the older 757, which finished 15th. Embarrassingly for Mazda, rivals Toyota and Nissan managed to finish 12th and 14th. Then the 767 was upgraded to become the 767B in 1989, which finished fifth at Daytona in preparation for Le Mans in June. The two 767Bs entered came in 7th and 9th, and the standard 767 finished 12th. With a 20th-place finish in 1990, the 767B was getting there from a reliability standpoint, but it just wasn’t fast enough. Nonetheless, it was the first step on the road to the 787B and Mazda’s ultimate prize – outright victory. There was just one looming storm on the horizon: The glorious Group C era regulations the Mazda raced under were coming to an end.

Politics, As Usual

Despite their rancorous relationship in the early eighties, by the end of the decade Jean Marie Balestre (FIA President), Bernie Ecclestone (Vice President of the FIA), and Max Mosley (President of FISA – the branch of the FIA responsible for governing motorsport) were by the end of the decade enjoying a mostly warm and mutually cooperative relationship. At that time, Ecclestone was simultaneously President of FOCA (Formula One Constructors Association), which meant he held the commercial rights for F1 and was responsible for organizing and promoting all the FISA-sanctioned series. Mosely also had another hat; as a trained lawyer, he was the legal representative of FOCA. He was the son of British fascist leader Oswald Mosley and Diana Mitford, socialites who married in Joseph Goebbels’ house with guess-who making the toasts. Mosley stated he got involved in motor sport because no one gave a shit about his background – which tells you a lot about the British upper classes.

So you had the mercurial and capricious dictator Balestre, the used car salesman with an eye for a deal Ecclestone, and the canny, socially-connected, sharp legal mind of Mosely. Together they ruled like a motorsport Politburo, though Ecclestone’s and Mosley’s dual roles represented a staggering conflict of interest that would make even FIFA President Gianni Infantino blush.

The oft-repeated rumor that Ecclestone was responsible for the death of Group C with an eye to making F1 even more popular (and thus increasing his already substantial personal wealth), is, on closer inspection, more complex. The initial spark that lit the firestorm was a 1988 post-Le Mans press conference (held at the circuit) in which Balestre unveiled a plan for the future of sports car racing: a 750 kg weight limit and a switch to 3.5-liter, normally-aspirated power units from 1991 – like those used exclusively in F1 from 1989. The stated idea was that a common engine specification would encourage more OEMs into sports car racing, but it failed to consider the fundamentally different reliability and fuel efficiency requirements between the two series. The new regulations also meant a more expensive race car, as the 3.5-liter NA units were really only an option for works teams with an existing F1 engine program. Under the previous rules, anyone could buy a 962 from Porsche and expect to be competitive.

Television

The other issue was television. Thanks to increased OEM involvement, endurance racing was exploding in popularity and the FIA recognized the value in providing broadcasters with a complete package of races for a season, as Ecclestone had finally managed to do with Formula 1. But endurance races of four hours (and one 24-hour one) were simply too long at the time to appeal to commercial television broadcasters, and Le Mans was run by the ACO – not FISA. Mosley saw sports car racing as a manufacturer’s championship rather than a driver’s championship: fans followed their favorite team as opposed to a particular driver. In a 1990 interview with Motor Sport magazine conducted by Group C reporter Michael Cotton, Mosley makes a series of illuminating comments about how he saw things:

Cotton: M. Balestre stated that the World Sportscar Championship would quickly build up to the same level of popularity as Formula 1; perhaps even exceed it. I’m not sure I see it in those terms, that what we used to call endurance racing should be turned into a TV slot, and anyway, everyone says that the atmosphere in sports car racing is much nicer. We’d like to keep it that way. If sports car racing is more about manufacturers than drivers, do you really think it can rival the popularity of Grand Prix racing?

Mosley: A lot of people hold that view, but I’m not sure that what they say is right. In the late 1960s there were huge crowds at Le Mans, when you had Ferrari versus Ford versus Porsche. You see, I can remember what the competition was but I can’t remember who the drivers were. Even last year there were a lot of people at Le Mans who wanted to see Jaguars, Mercedes and the Japanese cars, but I doubt if there were very many who could name the drivers of the first three cars. I am certain that if sports car racing is properly promoted, properly built up, it will be just as interesting to the public as Formula 1 is.

Cotton: We think that spectators are important to our series; I’m sure the manufacturers are concerned about the public, but you now exclude the public from the paddock and treat sports car racing as if it was Formula 1. The move to the top paddock at Spa, depriving the public of a view of the pit stops, is a manifestation of this. Are you sure we’re going the right way?

MM: You can only allow the public into the paddock if there are very few of them. If there are a lot of people it starts to get very difficult. In Formula 1 it’s not because we want to kick the public out, but it becomes impossible to work once the numbers exceed a certain level. At the moment the numbers are much smaller in sports car racing but we expect them to rise, and we’re trying to organise events on the same basis as Formula 1

In football you don’t allow spectators onto the touchline, or into the dressing room; it simply isn’t practicable. The enthusiasts may moan, but they can see similar cars at club meetings. They can get as near to an F3000 car as they like. World Championship events are not primarily for the enthusiasts; they’re for the general public and, of course, the media. I don’t mean that to sound offensive to the enthusiasts but it is the simple truth. There are too many people there to accommodate as they might wish to be accommodated.

Cotton: Now, no-one would think of competing at Indianapolis and Monaco . . . . Le Mans isn’t in the same category at all. All the major teams but one will be at Le Mans, and FISA has made life particularly difficult for them.

Mosley: The whole Le Mans problem lies with the ACO. I can’t think of any valid reason why the race should not be part of the World Championship, why they should not run their race to our regulations. I suspect that all this will be sorted out in the next year or two. It’s the responsibility of the French Federation to mediate between the ACO and the FISA, and a solution will have to be found. Every manufacturer, certainly would like Le Mans to be part of the World Championship, but if everyone gets busy from the outside that will just confuse the issue and slow things down.

Cotton: You represent the manufacturers who do want Le Mans to be part of the World Championship. Furthermore, if television rights are a major issue that’s in Bernie Ecclestone’s department. So, outside influences will be brought to bear. It’s not as simple as a negotiation between the ACO and the FISA.

Mosley: That’s true. I have to say to the FISA at every opportunity that the manufacturers want Le Mans to be in the World Championship, and FISA has to take that into account. As for television, I can see — as an outsider — that it isn’t possible to deal with television rights for the sports car series unless you can deal with all television rights.

1990 was meant to be the final year of the previous generation of “unlimited” cars raced up to that point. That year, Le Mans was not part of the overall championship, a deliberate divide and conquer strategy by the FIA aimed at wresting control of the race from the ACO, leaving a lot of OEMs not best pleased– including Mazda, who desperately wanted to win the 24 hours. Furthermore, other circuits and promoters now had to deal with FOCA, which increased fees and placed stringent restrictions on logistics suppliers, sponsorship, entertaining, and paddock passes – all subject to Ecclestone’s whims and control. According to an extremely detailed and well researched Reddit post, this caused disquiet among teams trying to sell a new expensive engine formula to their boards and corporate paymasters:

saw even more disarray. FISA declared Le Mans to be off the championship schedule – Balestre citing Mulsanne Straight safety concerns. This seemed like a slight hypocrisy as earlier that year FISA had pushed for the start of the Australian GP in Adelaide under frighteningly poor monsoon conditions. Even though chicanes were installed, Le Mans was being inspected while the world championship deadline came to a head. Manufacturers Aston Martin and Mazda backed out of their world championship bids, with Aston Martin closing shop and letting go 60 employees. Not to mention the Japanese manufacturers feeling like they were played – as they wanted Le Mans, not a championship which they were tricked to sign up for without it. Mercedes, working closely with Max Mosley, opted to forgo Le Mans altogether for 1990, staying to compete in the World Championship and not defend the previous year’s Le Mans win. This showcased part of FISA’s underlying strategy which was to divide Le Mans against manufacturer interest, leveraging change by means of withholding manufacturers from racing there if it wasn’t included in the World Championship.

Meanwhile, complaints began trickling from the teams once more. They cited issues with exclusivity in all manner of catering, shipping, hotel, and travel affiliations. Sponsor-requested passes were to be channeled through FOCA, and were usually hard to receive a Paris response. On top of the difficulty to obtain passes, the price per sponsor’s guests was astronomical (1990 WSC Silverstone: $500 per sponsor head). The paddock was also placed on a tighter security setting, restricting all but team personnel and journalists. Team and sponsor hospitality tents were removed as well. Teams also argued that this hurt sponsor interest as they weren’t able to properly market their investments. This occurred at the same time teams were trying to pitch a 3.5L car/engine proposal to their respective boards of directors. A pretty tough sell.

Formula One Cars In Drag

For the 1991 World Sportscar Championship the new 3.5-liter NA cars were the senior C1 category, with the older unlimited cars downgraded to C2. Crucially, they would be subject to an extra 100 kg (220 lbs.) of ballast. Jaguar, Mercedes, Peugeot, and Toyota had cars for the new formula, but Porsche was unwilling to develop a car without any guarantee they could dominate, so withdrew the works team from the series, their representatives being a number of customer 962s. These were dumped in C2 along with the venerable Ferrari-powered Lancia LC1 and the Mazda 787. Again, FISA competing in the full championship was a prerequisite for being able to take part in Le Mans.

A ground effects carbon fiber monster powered by a detuned Cosworth HB F1 engine, the Jaguar XJR-14 dominated the 1991 championship along with the fearsome V10 Peugeot 905 (the Peugeot engine would transition to F1 in 1994). Mercedes got in the game with their new 3.5-liter, flat-12 powered C291, which more closely resembled the older generation of Group C cars, rather than the F1 car in a cocktail dress approach Jaguar and Peugeot took. The 905 triumphed in the opening round at Suzuka, with Jaguar winning the next two at Monza and Silverstone. Mazda was nowhere – the 787’s best finish was sixth in Italy. Next up in June ’91 was the main event – Le Mans, back as an official FISA championship round after being excluded the previous year.

How The 787B Came To Be

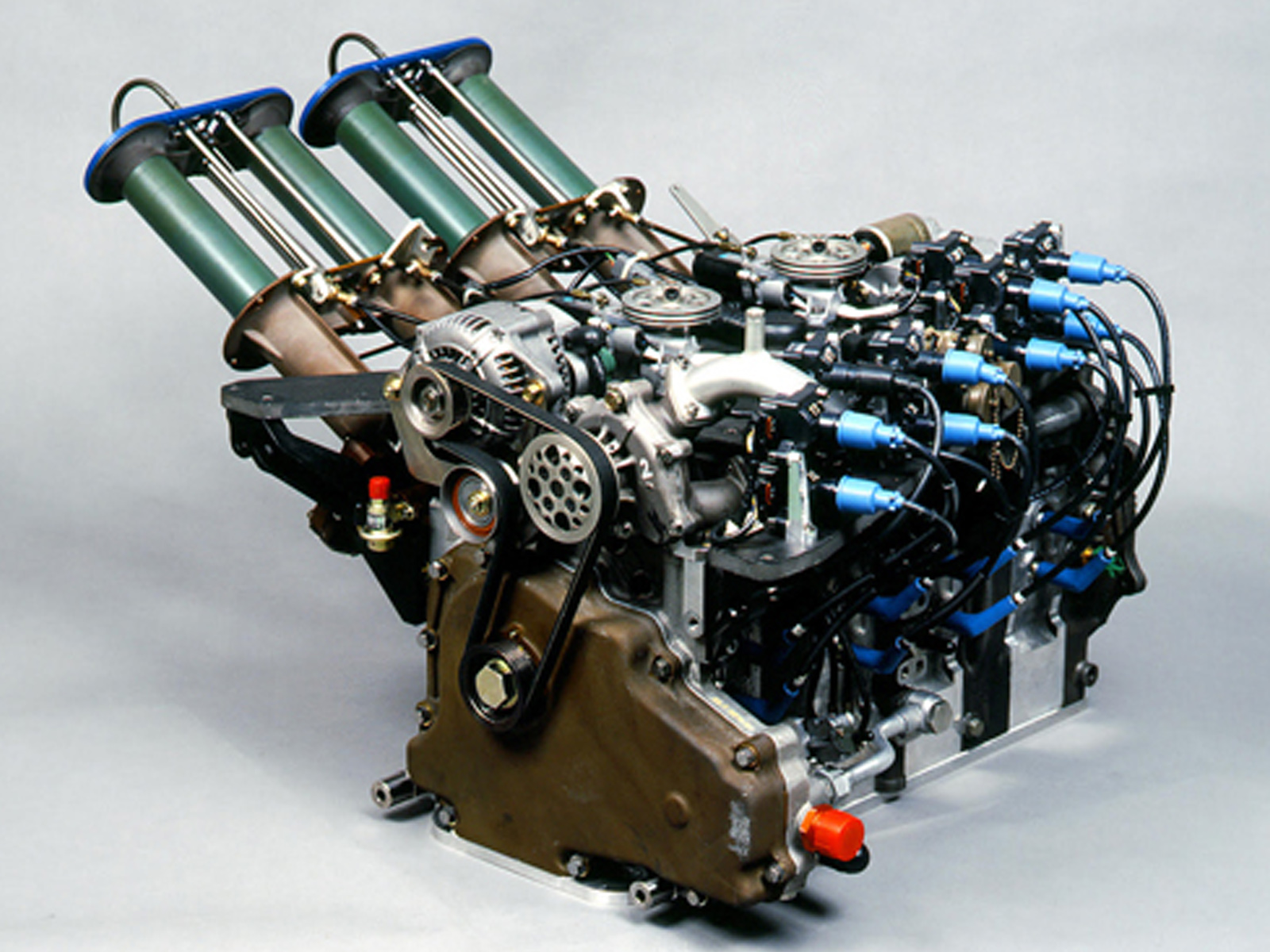

Back in 1989, Yasuo Tatsusomi, the senior executive in charge of Mazda product planning and development, watched the Le Mans race with interest. Seeing his company’s cars finish 7th, 9th, and 12th, he realized they were still not able to challenge for outright victory. The four-rotor 13-J bodge job in the 767 had gained a trick variable length intake system to become the 13-JM in the 767B of 1990, but at 630 bhp, it wasn’t enough, and the car finished a disappointing 20th at Le Mans. When Tatsusomi asked the team what they needed, long-time Mazda driver Pierre Dieudonné (who shared the Spa winning RX-7 with Tom Walkinshaw) told him they needed at least 100 bhp more. According to the website Japanese Nostalgic Car, Mazda racing program manager Takaharu Kobayakawa ran computer simulations that revealed the 787 needed to run seven seconds a lap faster while maintaining or bettering 13-JM’s fuel efficiency.

The all-new for 1991 R26B four rotor engine had several hard learned improvements over Mazda’s previous racing rotaries. Engineer in charge Yoshinori Honiden identified the causes of the 1990 engine failure as being the apex seals and inconsistent ceramic coating of the rotary chamber. Two-piece ceramic seal tips like those previously used on the old RX-7 13B motor and a new Carbide-based coating, which was applied to the rotary chamber using a new detonation gun process, solved the sealing problems. A third spark plug was added to improve combustion, and the fuel injectors were moved closer to the inlet ports, aiding throttle response and increasing fuel economy. For the nerds among you, a detailed engineering SAE paper about the R26B can is available here.

To complete the transition of the 787 to B-spec, there was a longer wheelbase for better stability and carbon brakes (a first) to go with the new engine. Significant modifications to the car’s aerodynamics were made – the main change was repositioning the radiators from the sidepods to the nose, which allowed to doors to be enlarged, allowing for quicker driver changes. After the disappointment of the 1990 race, Mazdaspeed enlisted the services of Le Mans legend Jacky Ickx. His advice was to thrash the 787B non-stop at race pace for 24 hours. To accomplish this, Mazda rented the high-speed Paul Ricard circuit in France – its 1.1-mile Mistral straight would be a suitable stand-in for the Mulsanne. In April 1991, the 787B duly pounded round for 24 hours without breaking down and managed to return even better fuel consumption than the engineers estimated. With three 787Bs now built, it was time to pack up the transporters and head north to Le Sarthe.

At the beginning of the 1991 season, Takayoshi Ohashi, now the Mazdaspeed team manager, secured a waiver for the 787 that would allow it to run at its existing weight of 830kg (1830 lbs.). FISA decreed 1991 would be the final year mixed grids in the championship would happen. From 1992, Group C would be exclusively a 3.5 NA formula. Mazda knew 1991 was their last chance to prove the rotary on the biggest and most punishing motorsport stage of them all, and it’s at this point we can put to bed another myth about the 787B. It was not banned for being too fast, too noisy, or to protect the European manufacturers. The rule change had already been decided three years earlier in 1988, with Balestre’s proclamation regarding 3.5-liter engines.

Runaway Horses

As discussed earlier, the rules for sportscar racing in 1990/91 were, to put it charitably, a total shit show. This led entry requirements for the 59th Grand Prix of Endurance that bordered on the farcical. Remember, FISA stipulated that you had to compete in the entire WEC to be eligible for Le Mans. FISA had expected to have a full grid, but only Jaguar, Peugeot, Mercedes, and Spice had built C1 3.5-liter cars. FISA attempted a waiver to allow Toyota and Nissan to take part, which pissed off Jaguar and Mercedes, so at the last minute, an emergency compromise was made: teams participating in the full WEC could run additional cars in C2 provided they had at least one car running in the C1 (3.5-liter) category. This ruled out Mazda’s archrivals Toyota and Nissan from competing with a stroke, but unwittingly played into Jaguar and Mercedes’ hands. They didn’t expect their highly strung 3.5-liter cars to last 24 hours, but they could now enter their old war horses for C2: the Jaguar XJR-12 that won in Le Mans in 1990 and the Mercedes C11. The C11 had dominated the 1990 season without racing at Le Mans, but its engine had been victorious in the back of the previous C9 in 1989. Because these cars had run under the older unlimited regulations, they would still be subject to the 100kg (220 lbs.) of additional ballast, but crucially, Mazda would not be so afflicted thanks to the waiver secured earlier in the year. Again, from the 1991 Autocourse season review:

In order to compete in the French classic a manufacturer had to have a car in the full series. The rules were written to allow teams to run their old fuel-economy machines, which had a far better chance of making the flag than the newer atmo cars used in sprints.

Neither Toyota nor Nissan, World Championship regulars in 1989-90, had atmo cars ready. Toyota announced it wasn’t interested in Le Mans but would be back with a new car at the final round; Nissan made every effort to get into the 24 Hours with its turbos on a one-off basis, while ignoring the other races. Had the company opted to run a token 1000 kg effort in the full series it could have competed at Le Mans; it chose not to, and paid the price. Jean-Marie Balestre made one misguided attempt to let all-comers into the race so as to bolster the field, but was soon informed in no uncertain terms that there was no way that Nissan should be allowed to take part.

The C1 entry list totaled just fourteen cars. Jaguar and Mercedes entered only one car each, and Peugeot two. Spice Engineering had a total of ten SE89 and SE90s entered across various customer teams – powered by DFR and DFZ versions of the old F1 DFV Cosworth engine. Interestingly, the AO racing team, which competed in the Japanese Sportscar Championship, entered their Spice SE90 with an all-female driver lineup: Desiré Wilson, Lyn St James, and Cathy Muller.

It was obvious the lower C2 category was where Jaguar and Mercedes now thought their best chance of winning the race outright lay. Jaguar took four XJR-12s, and Mercedes three C11s. Mazda entered all three of its 787Bs. At least seventeen customer 962s were on the entry list, along with a few randoms like Courage, who entered three of their own C26S cars and one 962. According to Autocourse, the only reason Jaguar took the XJR-14 to Le Mans at all was for a death-or-glory shot at pole position:

The XJR-14 was taken to Le Mans – but only for a cheeky shot at pole. Wallace was back for a one-off drive, and his pole attempt failed, much to Walkinshaw’s annoyance. The real effort was behind the four XJR-12s, superbly prepared as usual, with larger 7.4-litre V12 engines.

In the final tally, there were 32 C2 entries against 14 for the new C1 category. Of these, only 11 C1 but 28 C2 cars started the race. Whoops.

The Race

To make sure C2 teams didn’t get ideas above their station and to promote the new rules, FISA allocated the first ten grid positions to C1 cars, irrespective of their qualifying lap times. After a rain-lashed qualifying session, knowing full well they could not run for the full race distance, both Jaguar and Mercedes withdrew their sole C1 entries, leaving the two Peugeots on the front row of the grid. Behind them, Spice cars took up the remaining eight C1 grid slots. The ridiculousness of this arrangement is laid bare in the comparative qualifying times: the fastest time overall of 3:31.270 was by the C2 Mercedes C11 of Jean Louis Schelsser, which ended up 11th on the grid. The Peugeot 905 driven by Phillipe Alliot on the pole posted a best time of 3:35.058. The fastest Mazda 787B, car 55 (the eventual winner) managed 3:43.503 – 9th in C2 and 19th on the grid overall.

The morning of June 23, 1991 was damp and overcast, but by the time race started, it was finally dry. As the clock struck 4pm, the two C1 Peugeots streaked into the lead from the front row. By lap three, Schlesser was on the Peugeots tail in the C2 Mercedes C11 (that had set the fastest lap overall in qualifying, remember) having picked his way past the slower Cosworth-powered C1 Spice cars.

By 10pm, both the Peugeots were out, succumbing to engine and gearbox failures, proving the inchoate 3.5-liter cars were not yet developed enough for prolonged high-speed running. By now Mercedes held the first three places, the lead Silver Arrow driven by a young, superbly permed German called Michael Schumacher. I wonder what became of him. A Kremer team 962 had worked its way up to seventh, but the additional ballast caused a rear suspension failure.

Jaguar, seeing the pointlessness of chasing a decent grid position, had started 11th, 18th, and 21st. Because they had won in 1990 with fuel left over, they bored out the powerful but heavy V12 engine to 7.4 liters for extra grunt. However, that 1990 win was at 900 kgs (1984 lbs.), not the new FISA-mandated 1000 kg (2200 lbs.) limit for 1991. Consequently, their race pace was limited by the need to save fuel. After Wendlinger spun the lead Mercedes on cold tires after a pit stop, Jaguar was up to fourth place. Quietly capitalising on the retirements of others, the number 55 Mazda 787B had worked its way into fifth.

A stunning stint by Schumacher saw him drag the junior team C11 back up to third, which became second when, around 1 am, Jonathon Palmer brought his second-place C11 into the pits with handling problems. Now Mercedes were 1st and 2nd, Jaguar 3rd and 4th, and Mazda 5th. After Derek Warwick in the second Jaguar stopped due to engine problems, the lead Jaguar and Mazda began racing each other on the track for third. Wendlinger had taken over the junior team Mercedes from Schumacher, but got stuck in fourth gear and a half-hour pit stop to fix it dropped them seven places. The Mazda/Jaguar duel now became a battle for second place. With the Mazda able to run flat out and the Jaguar having to watch its fuel consumption, as the sun rose, the Mercedes of Schlesser, Jochen Mass, and Alain Ferté had completed 275 laps. The number 55 787B of Johnny Herbert, Volker Weidler, and Bertrand Gachot consolidated their second position, three laps behind. The two Jaguars were each a lap further back in third and fourth, the Schumacher, Wendlinger, and Kreutzpointer Mercedes junior team two laps behind them in fifth, with the remaining Jaguar sixth on 266 laps. But Le Mans hadn’t finished breaking race cars yet.

Schumacher, back in the cockpit, brought his Mercedes into the pits with an overheating problem, caused by a drive belt failure. Out in front, the lead C11 was beginning to do an impression of a steam train. At 12.50 pm, with only three hours and ten minutes of the race left and a commanding lead, the pit wall called Ferté into the pits as the temperature gauge became pinned into the red. As mechanics swarmed the car to replace the starter motor and water pump, their three-lap lead vanished like the cloud of white smoke the silver racer had just belched. Weidler in the 787B screamed through into the lead, the banshee wail of the 26B ricocheting off the pit walls to leave the beleaguered Mercedes team in no doubt as to what had just happened. The time was 1.05 pm – two hours and fifty five minutes before the checkered flag was due to fall.

At 2 pm, Weidler pitted and swapped over with Johnny Herbert for what was supposed to be Mazda’s penultimate driver change. Not wanting to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, Team Principal Ohahsi radioed Herbert and asked him to stay out until the finish, not willing to risk something going wrong in the final stop. From Mazda Stories:

As the final few hours of the race progressed, Mazdaspeed Team Principal Takayoshi Ohashi and Consultant Team Manager Jacky Ickx radioed Herbert asking him to extend his driving stint to the end of the race. With victory so close, Ohashi was unwilling to risk the uncertainty of an extra pit stop and driver change. Herbert agreed but, exhausted and badly dehydrated, it was only adrenaline that got him past the 24-hour mark to confirm the win.

The Herbert/Weidler/Gachot #55 Mazda 787B crossed the finish line in first place, having completed 362 laps. Despite their various setbacks, the three Jaguars finished second, third, and fourth – two, four, and six laps behin,d respectively. Their undoubted speed and reliability were hampered by fuel consumption issues that slowed their race pace and neutered their ability to fight for the win. A sterling effort saw the Mercedes junior team rescue fifth place, and incredibly for Mazda, the second 787B of Stefan Johansson, David Kennedy and Maurizio Sala finished sixth. The Joest customer 962 driven by Le Mans legend Derek Bell was seventh, and the third 787B crossed the line eighth.

The 787B Was Categorically Not The Fastest Car In The Race

On the face of it, all three Maadas finishing in the top ten is an impressive feat, but then so did all three Jaguars that started. It’s possible that the Jaguar XJR-12, a well-developed car built to hold a massive 7.4-liter V12, was strong enough to not break under the additional 100 kgs (220 lbs.), although it didn’t appear to upset the Mercedes handling or pace. Commenting on the C11 to Autosport magazine in 2022, Wendlinger said:

“In 1991 at Le Mans I think it was the fastest car on the grid,” says Wendlinger. “Unfortunately it was not reliable…”

Schumacher posted the fastest lap of the race at 10.45 pm – 3:35.5. That is within half a second of the Peugeot’s pole time, and remember, qualifying times are faster than race times. The 787B’s qualifying time was 3:43.5, so they were nowhere near Mercedes’ race pace. If the 787B had been saddled with the extra weight everyone else in their class had to carry, they would have been nowhere. The old motor racing chestnut is to finish first, first you must finish. And Mercedes didn’t, foiled by the classic $1 part. According to Autocourse, the 1991 running of Le Mans was Mercedes’ to lose:

After winning in 1989 and skipping the race in ’90, Mercedes returned to Le Mans in style with the C11. There was a hint of complacency in the preparation and, although the cars were crushingly fast, they had an Achilles’ heel. An obscure alternator bracket broke on two cars, and the same part might have gone on the third had it not retired earlier. The junior drivers salvaged fifth place, but the team was shell-shocked. Le Mans was a race Mercedes really should have won.

Was Mazda Lucky Or Just Fortunate?

So, was Mazda lucky? The Ancient Roman philosopher Seneca the Younger allegedly said, “Fortuna est quae fit cum praeparatio in occasionem incidit.” If you don’t benefit from a classical education, that translates as “Luck is what happens when preparation meets opportunity.” As I hope I’ve shown, Mazda was incredibly well prepared and experienced by the summer of 1991, but they had an incredible opportunity when the leading Mercedes broke. Another card that fell their way was FISA granting the 787B a weight concession, but that came about thanks to furious lobbying by Ohashi, Ickx, and the Oreca team, who ran the car throughout the 1991 season. It’s unclear, or rather, the reasons are lost to the mists of time, why FISA did this. It seems likely, given that the decision was made in April just prior to the start of the season, that there were three possibilities. Firstly, FISA wanted to keep Mazda in the series. Secondly, they didn’t expect them to challenge the other works teams given their demonstrable lack of competitiveness previously. Finally, Peugeot, Jaguar, and Mercedes were all too obsessed with what each other were doing to notice what was happening elsewhere, and so didn’t appeal FISA’s decision.

In reality, the 787B being victorious at Le Mans was a once-in-a-lifetime combination of luck and circumstance, engendered as it so often is in motor sport by the confluence of politics, money, and changing regulations. The 787B wasn’t the fastest, and it wasn’t the most fuel efficient (unbelievably, the C11 won the Index of Efficiency). So, can we place the blame for the 787B’s status at the feet of Kazunori Yamauchi, creator and producer of Gran Turismo? Given the Mercedes C9 and the earlier Jaguar XJR-9 (1988 Le Mans winner) have both been in the game since GT4 twenty years ago and haven’t really gained the same level of reverence, I don’t think that’s entirely the case either. Instead, the legend of the 787B has been created out of half cloth cut by overzealous rotary enthusiasts and JDM weeboos with anime profile pictures by cherry picking certain elements of the story and omitting others. And of course, Mazda itself seems determined to keep the unique engine in the minds of enthusiasts without currently having a compelling product powered by it.

Laying credence to Mosley’s 1990 assertion that sports car racing was a manufacturer’s championship, and possibly because Mazda wanted to emphasize the winning car over its drivers, I couldn’t find any images of the 1991 podium celebrations on the Mazda media pages. This is funny because whole sections of the Mazda site are devoted to the occasion. Thanks to his double stint, at the end of the race Herbert was too exhausted to take the podium (to make up for this, the ACO allowed him to take the podium during a 20-year anniversary event at the circuit in 2011). I’m particularly fond of Johnny Herbert because he is from the same part of the world as me, so it seems fitting to leave the last word to him. From Mazda Stories:

Herbert says the Mazda was “a lot easier than an F1 car” to drive, with downforce and g-force both significantly less aggressive. The cabin of the 787B was beautifully laid out and comfortable, and “the rotary engine was absolutely fantastic.” He remembers it as “silky smooth” and, crucially, bulletproof in terms of reliability. Herbert laughs when he recalls the gearbox as the “slowest in the world,” but it was designed for endurance over speed. While contemporary Le Mans teams can change a gearbox in five minutes during a pit stop, in 1991 the box had to last the full 24 hours.

Herbert insists the excellent 787B was a product of a team operating at the peak of its powers. Ohashi was “very shrewd and had a great sense of humor.” He had spent the previous decade enrolling some “brilliant engineering minds” and embraced a truly international recruitment policy, getting in the likes of British car designer Nigel Stroud and Belgian six-time Le Mans winner Ickx as an advisor and consultant team manager.

“Mazdaspeed was a very small team compared to the might of the competition, such as Mercedes-Benz and Jaguar,” [Ed note: ?! – AC] says Herbert. But by June 1991 the team was “in a perfect position because it had been through a huge learning process” over the previous years. Seasoned drivers such as Pierre Dieudonné and Yojiro Terada (among others) brought experience to the Mazdaspeed driving roster and, despite being considered underdogs, there was no doubting the “hard-earned” nature of the victory that would come.

Actually, no, it’s my story, so I’m going to have the last word: The reason the 787B is so loud is the screaming of the fanbois and girls.

Excellent article! The reason the 787 is popular is exactly the fans, it’s weird, it’s the Japanese winner, it was perfectly positioned to become a legend, and legends garner mythology to go with them. Always good to set the record straight with some history!

Holy shit…that was an amazing article. Very insightful.

I was lucky enough to see the 767B running laps in Adelaide last year – the sound of the quad rotor deserves all the attention it gets!

Always enjoy some AC content

And I enjoy you enjoying it. Thank you for reading.

Outstanding, as always.

Excellently-researched and brilliantly written. Long form stuff like this is why I am a member

And we’re pleased to take your money.

Outstanding content.

Have I ever let you down?

Mazda could do the usual corporate thing and sue Boeing for the 787 trademark. But I hope they’re classier than that.

You can’t trademark numbers in the US. Hence why Intel went to “Pentium,” rather than 586.

Ah. My kid went to law school. I didn’t. He probably knows all the fine points of that stuff. I don’t.

Nowadays it’s written that the R26B made 900hp but everything from Mazda says 700. I don’t know where it came from but that figure was being bandied about a little over 10 years ago and it’s now crept into magazine articles. Even if it was detuned for Le Mans with that much power it would have done a lot better at the shorter races.

People forget that the rotary was more often underpowered compared to its rivals, but it was one of the few engines that could be driven at qualifying pace for 24 hours so it did well in endurance races. That’s why the IMSA RX-7s always did well at Daytona.

Another funny way history gets distorted is in the Haynes Jaguar XJR-9 book it’s claimed that Mazda had no fuel limit at Le Mans.

Pierre Dieudonne wrote a book about Mazdaspeed’s Le Mans program, it was a lot cheaper when I got mine years ago. The other 787B would have placed higher but driver David Kennedy was sure it was going to rain heavily and chose a shorter final drive ratio. He’s still kicking himself today.

Excellent additional info, thanks. I have that Haynes XJR-9 book so I’ll have a look.

What an awesome read. Being a Mazda head, I always knew they won because a lot of cards fell their way and never would have won on outright pace. But I didn’t know just how deep the story went. I knew enough to not be jaded. Overall though, what a great era of racing.

Well researched. I remember there being lucky circumstance, but didn’t know nearly all this detail. So it goes with sports and war, it doesn’t always matter who’s better if the opponent is luckier. Equipment and preparation increase the odds in your favor, but sometimes it’s just not your day. I don’t recall ever hearing any of these ridiculous claims about the 787B, but I haven’t really played video games since I was a kid and I tend to not hang around with other car people so I’ve only met two rotary whackados in real life (that I avoided conversation with after—they only wanted to talk about rotaries like some weird cult desperate for recruits).

I am a simple woman, I just like it because loud racecar noises…

Not the fastest, but definitely the loudest.

I was at Daytona in 79, the first year Mazda ran the rotary engined RX-7’s and they were without a doubt the loudest cars I’ve ever heard. They reminded me of the old unlimited outboard powered hydroplane boats – the noise was ear splitting, and not in a good way. After that race and for the rest of the season they had to run mufflers.

A friend ran a 13B in his RX3 and later in a tube framed Miata, his “muffler” consisted of a SS tube filled with lave rock, the only thing that would stand the heat!

That closing sentence sums up all the acrimonious glory of a bowel-harassed goth writer.

Thank you, uncle Adrian, it was a spectacular piece of sacred cow desecration, even when I hold Mazda in high esteem.

Instructional and entertaining, it was well worth the wait, congrats!

Please sir may I have some more? Any topic or subject you fell like blessing us with…

I’d gladly read a dissertation on the merits of Chiltons vs Haynes.

Fantastic article as usual and glad you have recovered from your illness.

It took me two days but that was a bloody fabulous article (More like short story, eh? Wink wink nudge nudge). Glad Adrian is back at it!

Also genuinely enjoy the longer form stuff like this, would love to see more deep dives occasionally.

Your article has had the opposite effect on me. I love the 787B for its novelty, but I always knew it was significantly slower than its competitors. I used to see Mazda as being lucky, possibly undeserving. But your article is so comprehensive, it made me realize how hard Mazda worked to make the 787B happen. All of the failure, the lessons learned, the re-development, the exhaustive testing. It’s a wonder they didn’t axe the project sooner, but they stuck it out and they were rewarded for their perseverance right before the regulatory window closed. Now I actually feel like Mazda deserved the win. Sorry if I took the wrong lesson from your article. And it’s one of the best articles I’ve read on this site to date.

Same thing happened to me. I would read a paragraph on how it was slower and less deserving than the other cars, and then Adrian would post a warm, grainy photograph of that orange and green 55 and I would forget all about it. I do wonder if it would be remembered as well if one of the other Mazdas took the checkered flag.

Same. Appreciative of the clarification, though it only adds to it’s legend.

It reminds me of book published about two manufacturers racing in an endurance race in the late 60’s which made me root for the company that didn’t spend millions of dollars to win

I think both determinations are valid. Often, it’s the “undeserving” winners that make for the more interesting stories. I suppose the question then is: why would shear, stubborn will alone not qualify as deserving?

It was a totally different era and mindset too with endurance racing. Yes the cars were outrageously fast but weren’t expected to basically run a 24 hour sprint like they are nowadays.

Sometimes just showing up and running your own race can pay off. Pumped for the Rolex 24 this weekend. Racing is back!

just gonna leave this here… the only thing missing from the article to make it a complete experience.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sxXtpMngivM

This was a hella long article, but well worth the time. I just want to thank “Uncle Adrian” for the history lesson.

I had never learned that bit about Colin Chapman, and it was an absolute delight to learn that Johnny Herbert (one of my favorite drivers from the BTCC) had been one of the drivers for the LeMans-winning Mazda. And I was also pleased to read about how much effort ACO put into keeping LeMans separate from the WEC/whatever-it-was-being-called-at-the-time.

Yeah, Chapman escaped* while DeLorean’s name is synonymous with coke distribution (it was entrapment!).

*By escape, I mean he died, but while that might seem obvious, I did read a claim by some nut that he faked it to escape prosecution.

This line stood out to me as just how razor tight the engineering is on cars at this level. The idea that making the car 200lbs heavier did in the suspension.

TL;DR, Mazda won for two reasons:

The underdog portion, in my opinion, was the engine choice. In the end, it was the most reliable mill. Which is antithesis to everything the Rotary Haters say.

I feel that more unlimited classes should exist. Give them a fuel limit and a weight minimum, let ‘er rip.

This is why I love the unlimited time attack classes. You have a track and a clock. Be faster than everyone else.

I experienced full on CanAm at Trembant and Edmonton back in the heyday of the series. Mad, snarling dragons don’t come close to a 750 hp 8 liter 1500 lb unlimited race car of those days.

Lobbied my father for months before he agreed.

I’d love to go to Lemans. I still watch f1 and a few other series. The commercialization and politics have lowered my interest a bit.

I just wanna see what happens when engineering teams are allowed to build in an environment where they only have to answer to physics.

I’ll bring the refreshments!

Perfect, cause my liver and BAC also only answer to physics.

I’m off all alcohol and sodas now. Water and natural juices only ???? I’ve got an unopened bottle of Woodford Reserve Double Oaked sitting forlornly with its Scottish friends on the drinks shelf. Maybe next year I keep telling them, and myself.

Edibles are legal up here, so I’ll sub for water, coffee, and 5mg (yes, I know I’m an edible lightweight).

I’m good with that!

That’s basically what Group C was when it was introduced. Fuel limit, weight limit and dimensional contrastraints.

Next up, let’s revive

Death RaceGroup B Rally!Peugeot stage mechanics: what’s for dinner?

Peugeot crew chef: spectator fingers a la radiateur hon hon hon

Wow

I was starting to wonder if Adrian had found greener pastures, glad he’s stayed here.

The truth of the matter is that I absolutely loathe racing news, history and all of it. It feels as if bureaucracy was bored and decided to ruin fast cars with a million GD rules and regulations. Like when you were a kid and you’re playing some sort of made-up game and then THAT fucking kid shows up making a million rules, trying to boss everyone around until someone just hucks a ball at his head so he’ll shut the hell up and ideally go away.

However, this article certainly brought in the spoonful of sugar that got the racing rules and other nonsense down wonderfully.

This is the sort of writing that the world need more of.

There are no greener pastures. There is this salted wasteland of weeds and graves and nothing else.

That’s similar to why I liked some sports as a kid, but never signed up—too many rules, forced to do it on someone else’s schedule, and too competitive. I like to have fun and get better through practice and observing better players, but I don’t care about the scores. So, yeah, nobody was missing me on their team, anyway!

When I bought my Harley after I passed my bike test I looked into joining the club for the social aspect, and to do ride outs with. Their list of rules for ride outs was insane. Talk about playing army officers.

Sounds like they might be similar to the kinds of people who take paintball seriously.

For me, the problem is that I like a lot of things, so no one thing is my life, and any club I’ve checked out is full of people who are seriously into that one thing with often little interest in much else or they’ve even made it a large part of their identity. Other times, it’s a specific focus over the broader whole (eg, a single model of car vs interest in most cars). Logically, it makes sense that those who’d join a club would be so single-minded, but it’s frustrating when I’m trying to appease an ornery brain that insists that I should be more social. Good thing is that, since I once met up with a guy from elementary school at the brain’s insistence and he ended up being a weird creep who was later imprisoned (and still is, I believe) for torturing some poor woman in his apartment for months, it’s been fairly quiet.