Traveling just about anywhere in America today is trivial for most people. No matter where you want to go, there’s going to be some sort of car, motorcycle, plane, bus, train, or boat that can get you there. Two centuries ago, traveling in the United States was very different. The steamboat changed travel history, allowing masses of people to travel great distances in only days. It wasn’t long before Americans started racing these majestic machines, and America became obsessed with watching boats slowly steam up rivers, often just to see those steamers blowing up in a deadly manner.

Water-based travel before the steamboat was not easy. Sail power was dominant, but if the wind could not be used to move watercraft, muscle power from humans or animals was often used instead. This was incredibly inefficient and made what would be a simple river crossing today quite the ordeal back then. Other times, flat-bottomed boats were built far north, were then loaded up with cargo, and then sent south with the current of the river. Since it was impossible for those boats to sail north again, they were often scrapped at their destinations.

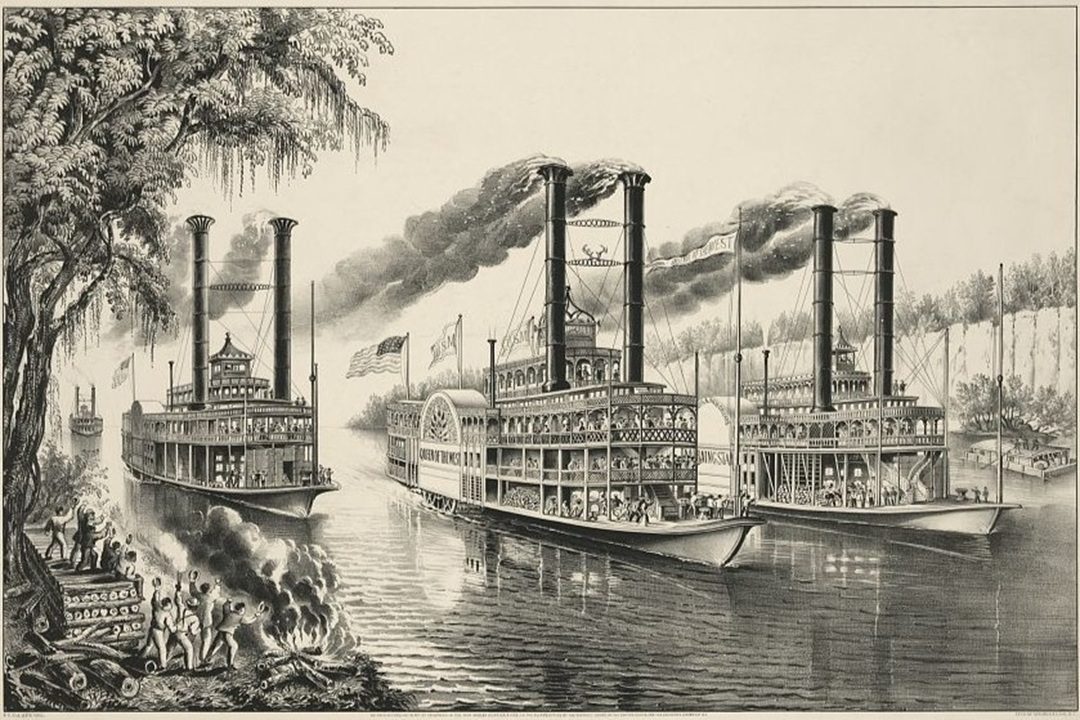

As the Smithsonian Magazine notes, if you were to define “steamboat” broadly, it describes any boat powered by steam. However, the typical usage of steamboat describes the steam-powered vessels that prowled America’s interior waterways throughout most of the 19th century and much of the 20th century. These craft were usually propelled through paddle wheels mounted to their sterns or sides. Following this theme was the steamship, which was also powered by steam and, back in those days, were also paddle wheel vessels, but were built to handle oceans rather than lakes and rivers.

Many of them would find themselves racing.

Setting The Stage

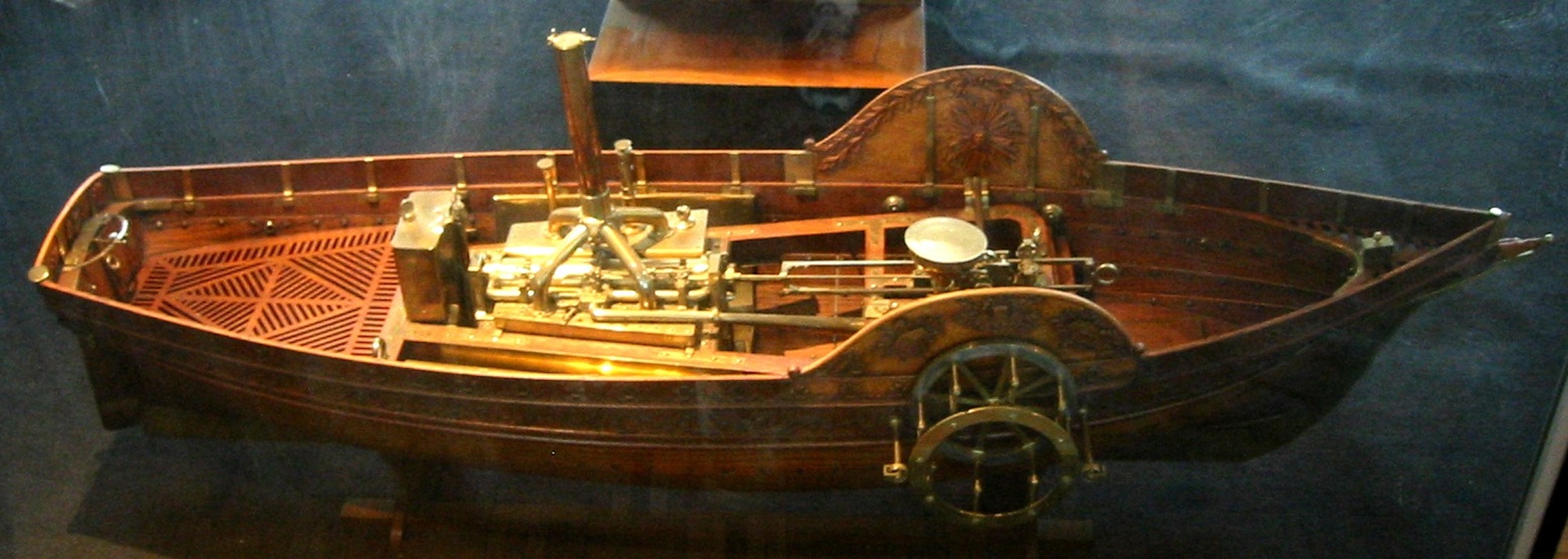

The first known successful steamboats in history didn’t come very long after James Watt of Scotland invented a practical steam engine in 1765. In the summer of 1783, Wired writes, French inventor and engineer Claude-François-Dorothée de Jouffroy, the Marquis d’Abbans, demonstrated what is believed to be the first practical steamboat. De Jouffroy’s steamboat used a steam engine of Watt’s design and connected it to a pair of paddle wheels. This wasn’t de Jouffroy’s first steamboat, but his second. The first used a Thomas Newcomen steam engine (the original design of which dated back to 1712) and tried to propel itself through water using rotating paddles that resembled the feet of a waterfowl. This original design went nowhere.

De Jouffroy’s paddle wheel steamboat, the Pyroscaphe (Greek for fire-boat) was a marvel. It measured more than 148 feet long and displaced 163 tons. The steamboat’s crew of three cruised up the Saône in Lyon at 6 mph without sails or men rowing. Apparently, this engine was powerful enough that the steamboat began breaking up after 15 minutes, and the crew landed the boat on shore before things fell apart. De Jouffroy landed to a cheering crowd, and he would go on to test steamboats for nearly a year and a half after.

Amazingly, due to reportedly petty political reasons, de Jouffroy was never recognized by the French Academy of Sciences. He never got a patent, even though his invention would change the world. Even when the French Revolution rolled around, de Jouffroy was never given recognition. De Jouffroy died from cholera at the age of 80 in 1832, largely penniless and defeated.

Over in America, John Fitch is often credited with being one of the greatest steamboat pioneers after building steam-powered boats propelled by paddles, paddle wheels, and propellers.

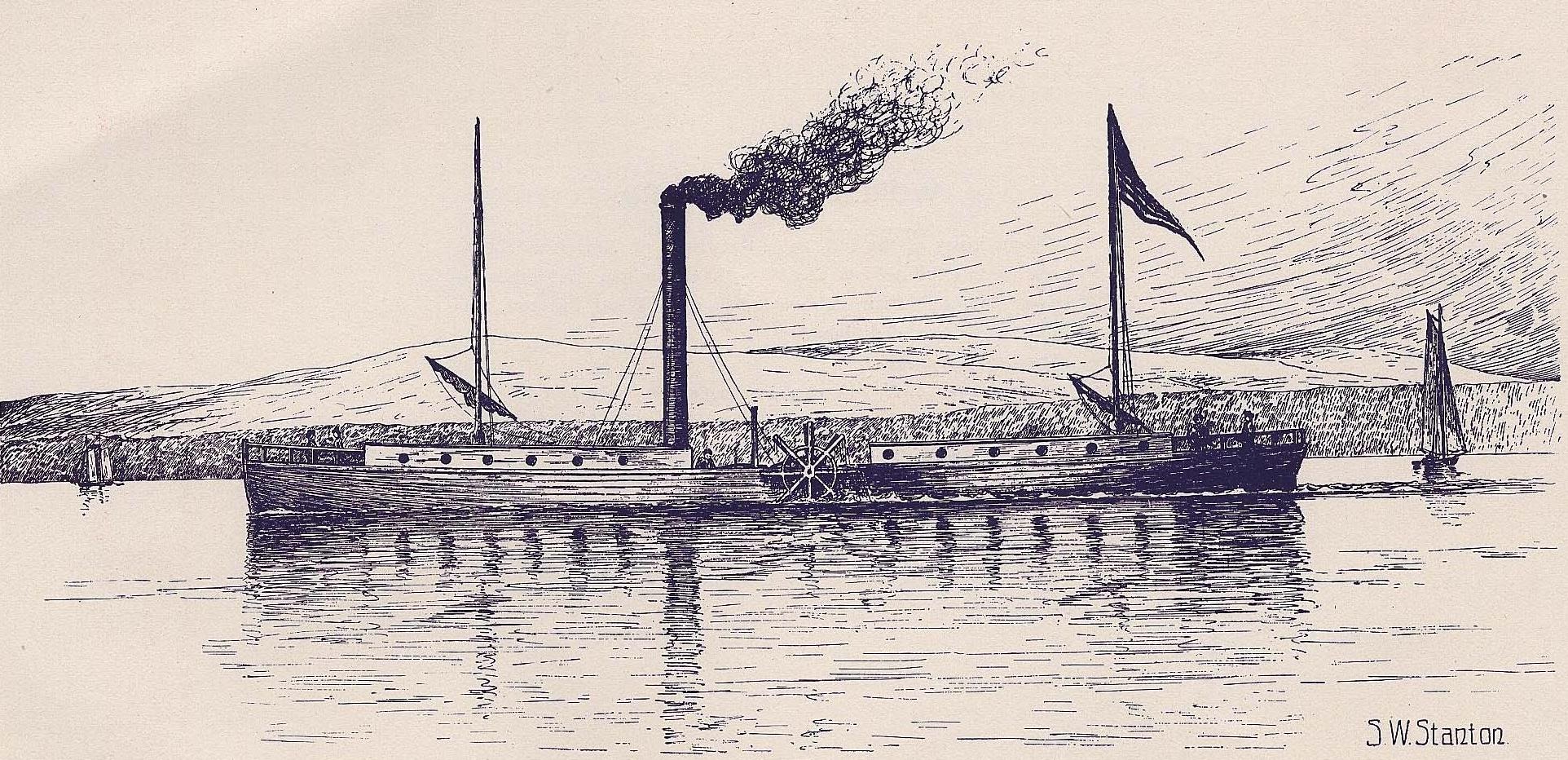

Then came Robert Fulton and the steamboat Clermont (below). Fulton’s Clermont is credited with being the first commercially viable steamboat. In 1807, the Clermont loaded up with passengers and paddled from the New York harbor to Albany in 32 hours at a speed of 5 mph, proving that steamboats were more than just cute novelties.

Thanks to the muscle of steam power, travel was faster and more comfortable than it had ever been before. From the Smithsonian Magazine:

“The steamboat was the first American invention of world-shaking importance,” wrote historian James Thomas Flexner in 1944. In fact, he added, it “was one of those crucial inventions that change the whole cultural climate of the human race.”

Naturally, steamboats captivated Americans in the early 1800s. These were grand vessels that utilized mechanical marvels of engines and could move in any direction regardless of which way the river flowed. A steamboat could power up the mighty Mississippi River, unlike the boats of the past.

Enthusiasts Will Race Anything

As steamboats multiplied, people suddenly began wondering which ones were the fastest. As the Smithsonian Magazine writes, the first steamboat race in America was likely the one that occurred in 1811 when Robert Fulton’s The North River raced the Hope. The two steamboats departed Albany and attempted to race to New York City at the blistering speed of 5 mph. Ultimately, the boats’ captains called the race a draw after the two steamers collided. This was only the beginning, as steamboat racing spread across America’s rivers and even the Great Lakes.

However, America’s fascination with steamboats came with an unfortunately dark reality, and it was that these boats were often horribly unsafe. It was believed that steamboats were deadlier than even oceangoing steamships, from the Smithsonian Magazine:

Useful as steamboats were, they came with one big problem: They were inherently dangerous. The boilers they used to make steam were prone to exploding and igniting fires. Not only were the boats built mostly out of wood, but their cargos also often included highly flammable cotton bales, along with barrels of turpentine and gunpowder. The waterways themselves presented numerous hazards, including “snags”—large tree limbs and uprooted trees that either floated atop the water or lurked beneath the surface. As rivers became more congested with traffic, steamboats also ran the risk of colliding with other boats, particularly at night when they had to use torches to light their way.

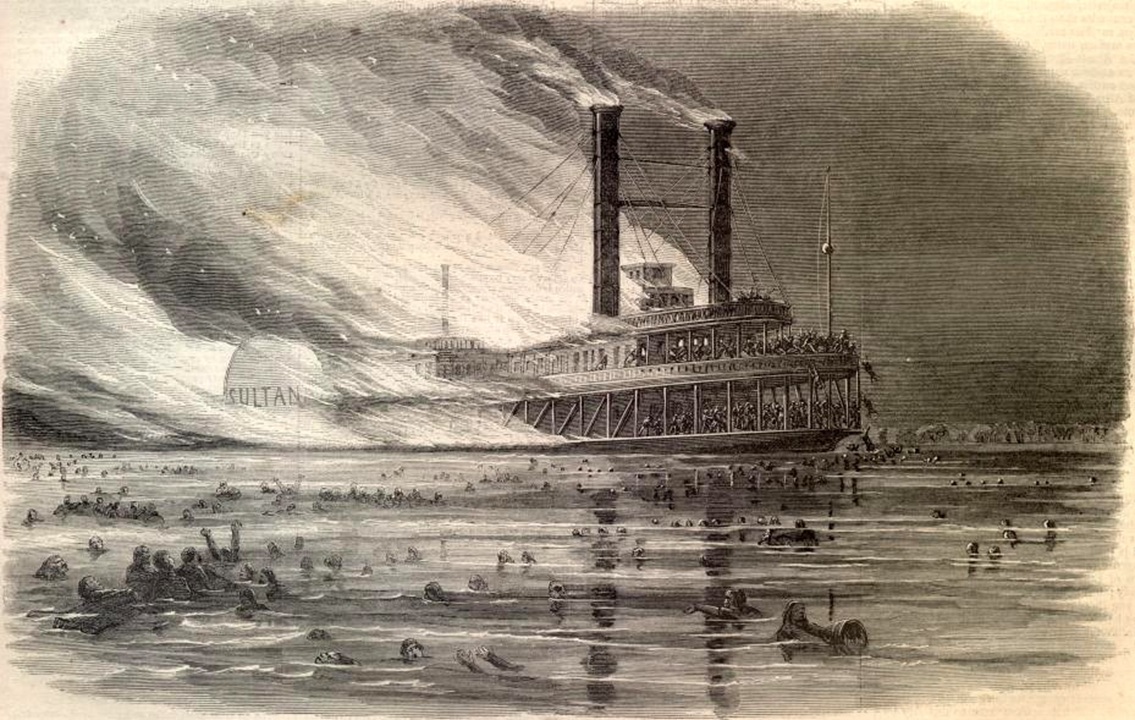

Between 1816 and 1848, boiler explosions alone killed more than 1,800 passengers and crew and injured another 1,000, according to government records. The sinking of the steamboat Sultana in 1865, also the result of a boiler explosion, claimed as many as 1,800 lives—still the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history. “Western steamboats usually blow up one or two a week in the season,” Charles Dickens observed after an 1842 tour of the U.S.

One of the most horrific accidents occurred in 1838, when the Moselle, a fast and nearly new Ohio River steamboat, exploded off Cincinnati. “All the boilers, four in number, burst simultaneously,” reported one contemporary author. “The deck was blown into the air, and the human beings who crowded it were doomed to instant destruction. Fragments of the boiler and of human bodies were thrown both to the Kentucky and Ohio shores, although the distance to the former was a quarter of a mile.” At least 120 people died, but the exact death toll remains unknown.

You read that right, thousands of people died in steamboat explosions and sinkings that happened on a regular basis, and that’s when these boats were not racing. As the American Heritage magazine writes, if you were afraid of dying in a steamboat explosion, some boats towed a smaller boat behind them. For twice the price of a normal ticket, you could enjoy the speed of a steamboat in the towed boat, but far away from exploding parts.

Taking steamboats to their absolute limits just to figure out which boat was slightly faster only made things worse, but America loved it, just like Americans loved crashing steam locomotives into each other just for the fun of it. Reportedly, steamboat races got so serious that, sometimes, boats wouldn’t even stop to unload passengers at intermediate destinations. Instead, they dumped those passengers into smaller boats while the steamboat moved at full speed.

Steamboat races were more than just about seeing who could go the fastest. The captains of these boats considered winning races as points of pride, and the owners of the boats used the wins as advertising to sell tickets. Spectators of steamboat races pumped money into local economies, and gamblers placed huge bids on races.

The infamous P.T. Barnum once arranged a steamboat race between the Messenger No. 2 and the Buckeye State in 1851. The two steamboats raced down the Ohio River from Cincinnati to Pittsburgh to promote singer Jenny Lind. Barnum and Lind, who rode aboard the Messenger No. 2, lost the race, but they generated so much publicity that Barnum made piles of cash, anyway.

Basically, so much of America found some way to enjoy or profit from steamboat races. Of course, keep in mind that we’re talking about achingly slow boats here, too, even though it probably reads like I’m describing something much faster. Apparently, Mark Twain loved the spectacle, including the high chance of injury or death, as the same Smithsonian Magazine piece notes that Twain considered horse racing tame by comparison, noting that he’d never seen anyone killed at a horse race. American Heritage magazine writes that steamboat racing was such a huge draw that newspapers sometimes pushed boat owners into racing through sensational articles:

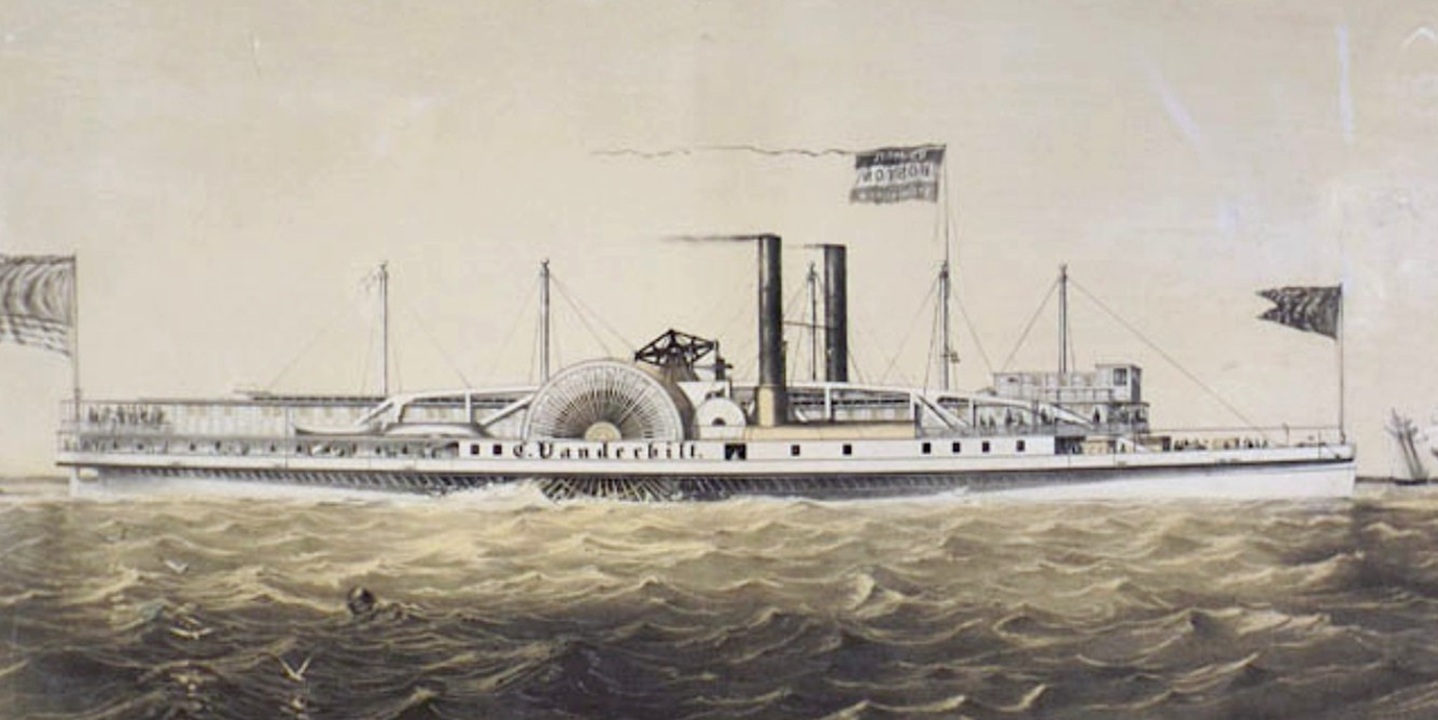

On May 26, 1847, the New York Herald ran a brief article under the headline SPLENDID AFFAIR. “We learn,” the story ran, “that George Law, Esq. the owner of the famous steamer Oregon has challenged the proprietors of the new steamers Bay State and Cornelius Vanderbilt [the Commodore had named his latest boat after himself, although she was properly called the C. Vanderbilt] … to make a trial of speed of these splendid steamers;… no passengers to be taken. This will be a splendid affair, and no risk run by uninterested individuals. …”

Robber baron Cornelius Vanderbilt was big into steamboats, and other boat owners wanted to prove they were better. He also took the newspaper’s bait and said his steamboat C. Vanderbilt would race anything that George Law could come up with for a bet of $1,000 to $100,000. George Law, Esq, the owner of the steamboat Oregon, accepted a $1,000 bet, and the two boats would compete in a race in a round trip to Sing Sing and back.

The Smithsonian Magazine notes that the two boats were largely evenly matched. The Oregon had a more refined hull design, allowing it to travel fast in water without having as much power, while the C. Vanderbilt had a huge engine. Yet, the race was apparently a hot one. The C. Vanderbilt accidentally stopped its engines during a U-turn on the race. Then, the Oregon accidentally ran out of fuel and was forced to burn thousands of dollars in chairs, beds, and doors to remain in the lead. Ultimately, the Oregon won by a quarter mile, and did so by more or less burning its own interior.

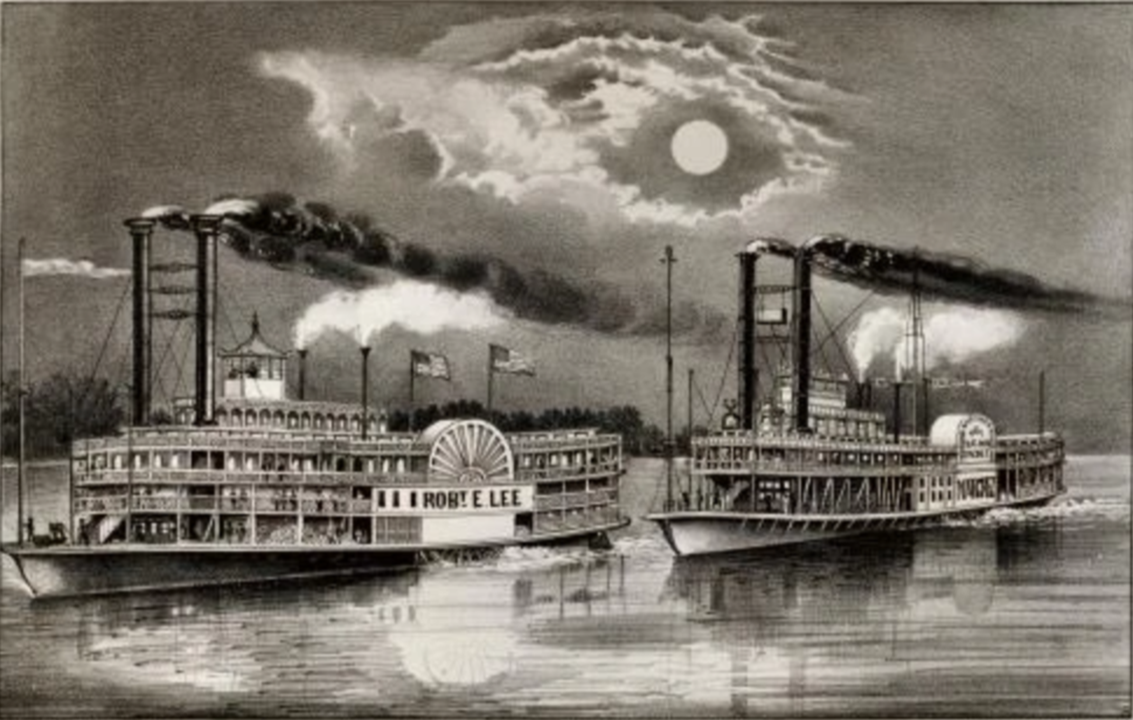

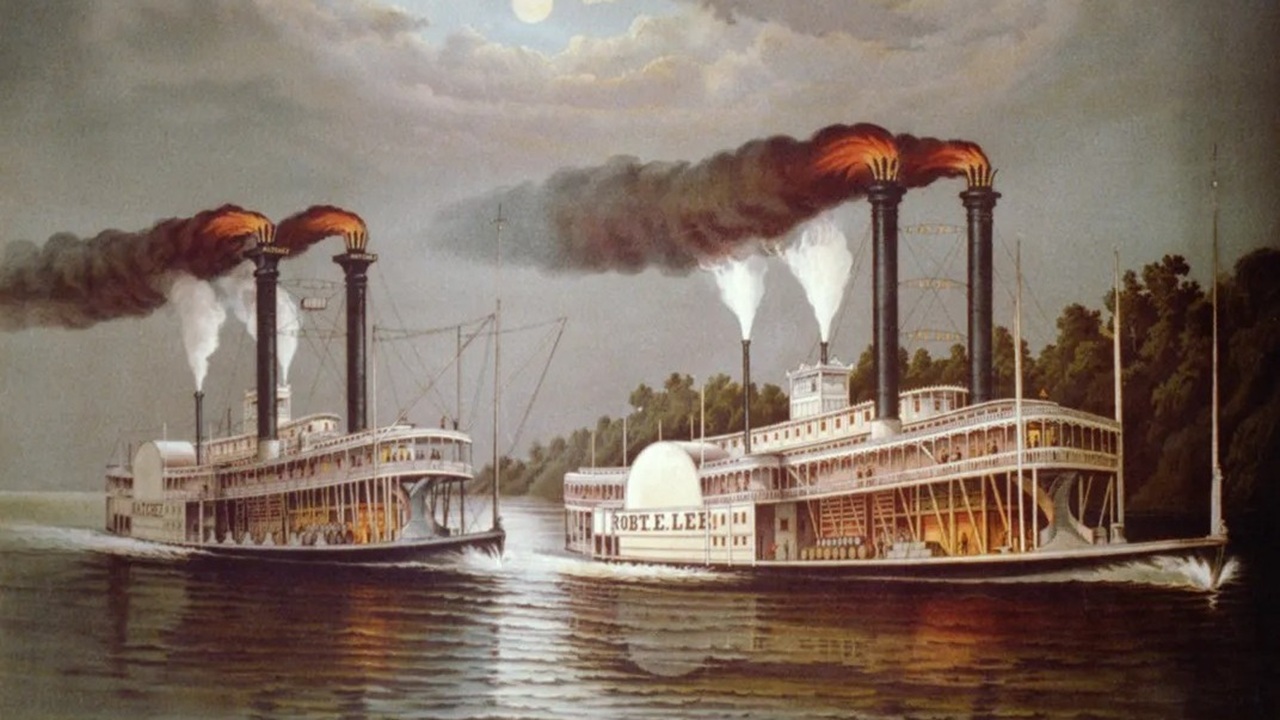

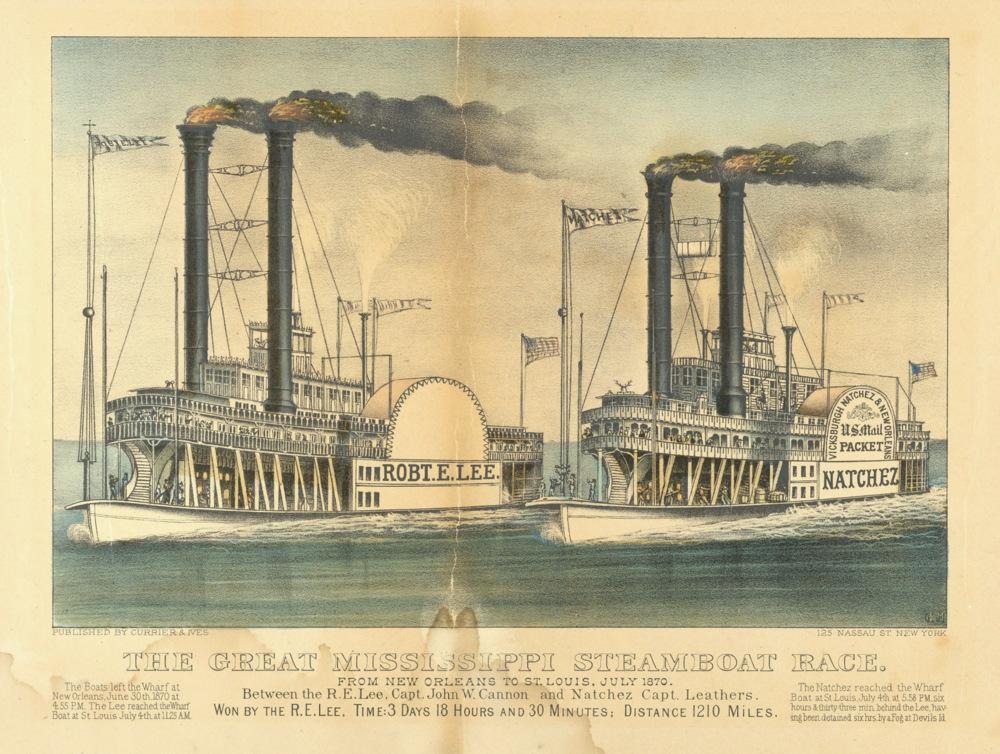

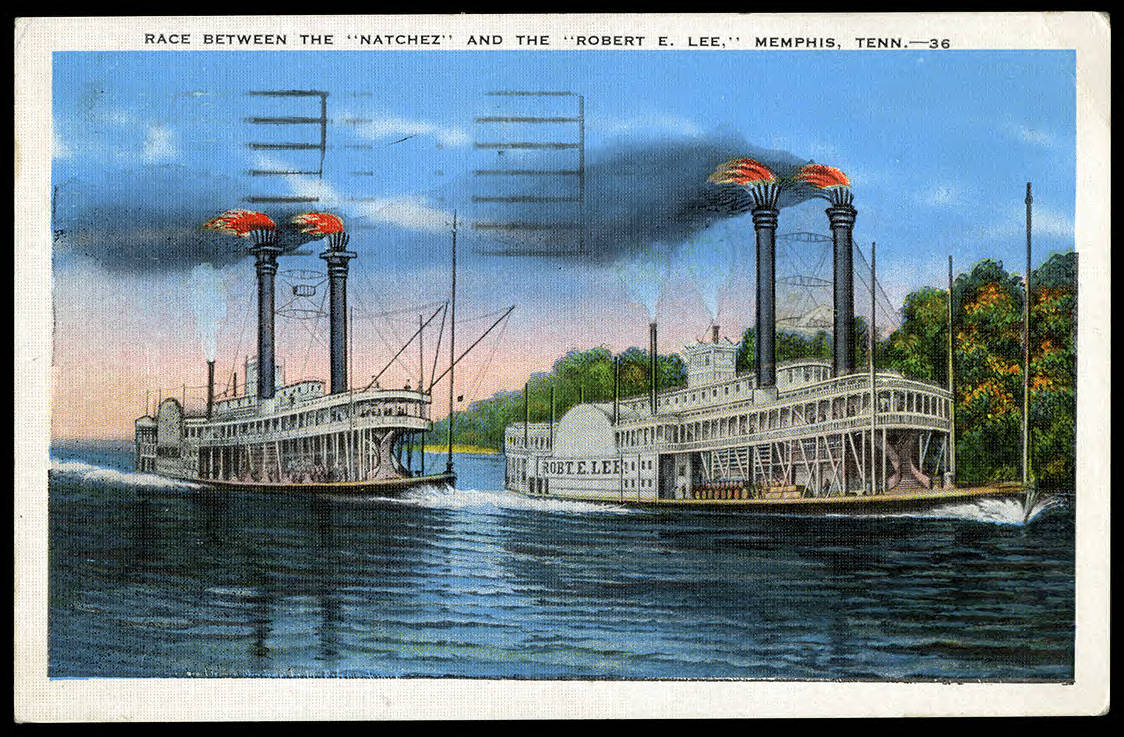

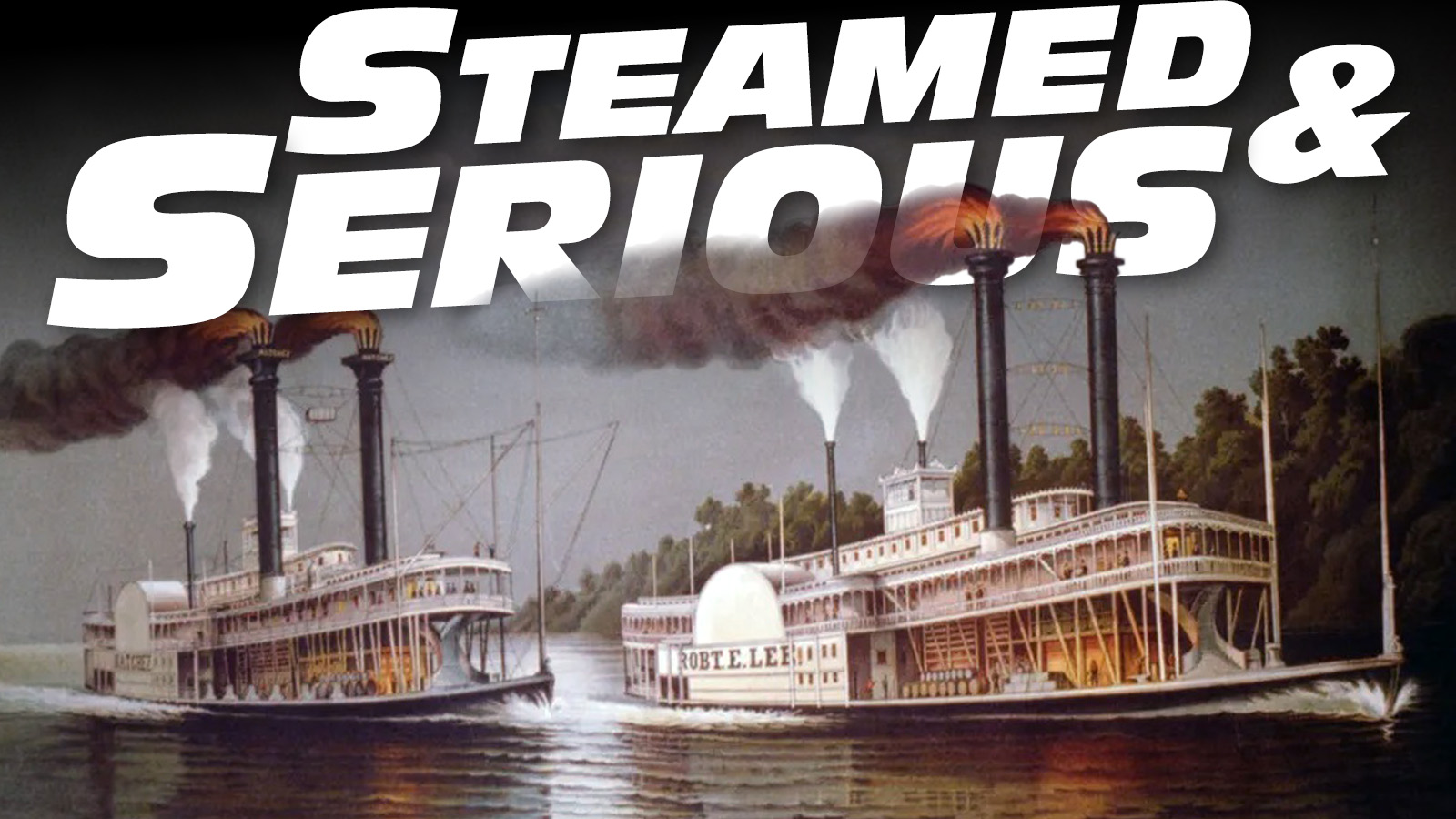

The most famous steamboat race of them all was probably the multi-day, 1,200-mile extravaganza up the Mississippi River between the steamboats Robert E. Lee and Natchez in 1870.

The Great Mississippi Steamboat Race

As the Louisiana history publication 64 Parishes writes, the American South was rebuilding in the aftermath of the Civil War, and there were only a few local festivities to bring the spirits of the people up. Likewise, by 1870, steamboats were quickly losing their fame as steam locomotives had become the new fascination of the nation. That was until two famed captains, Thomas P. Leathers and John W. Cannon, decided to arrange one of the wildest steamboat races in history.

Here’s what 64 Parishes says about the captains:

Gruff, profane, and physically imposing, fifty-four-year-old Thomas P. Leathers grew up in the steamboat business, building his own boat at age twenty-four, and labored his way to the top. By the time of the Civil War, Leathers had owned five consecutive steamers, each named Natchez, and each larger and faster than its predecessor. In 1861, the fifth Natchez carried Jefferson Davis to Montgomery, Alabama, where he was sworn in as president of the Confederacy. Leathers lived in New Orleans and aggressively nurtured his own brash reputation up and down the Mississippi River.

[…]

Other than an abundance of experience in the steamboat industry, fifty-year-old John W. Cannon had little in common with Leathers. A quiet, astute businessman, he had owned at least a dozen steamers and managed to make a small fortune hauling freight during the war. His wartime profits were used to build the Robert E. Lee. By then, he had learned first-hand the dangers of his occupation when the boilers on his boat, Louisiana, exploded at the New Orleans wharf, killing eighty-six people in 1849.

Leathers and Cannon were well-acquainted business rivals and personal adversaries. Leathers often challenged Cannon to race. Once, in a New Orleans tavern, the hostility turned into a fistfight in which an onlooker said Cannon got the upper hand. As Leathers’s challenges mounted, newspapers and Cannon’s customers up and down the river encouraged him to race. Reluctantly, he relented, preparing for the race in a methodical, businesslike manner. He stripped the Robert E. Lee of all unnecessary weight and made arrangements for mid-stream fuel deliveries all the way to St. Louis. No freight was carried and the passenger list was restricted. In contrast, Leathers, exuding confidence, stated that he would carry a routine load of passengers.

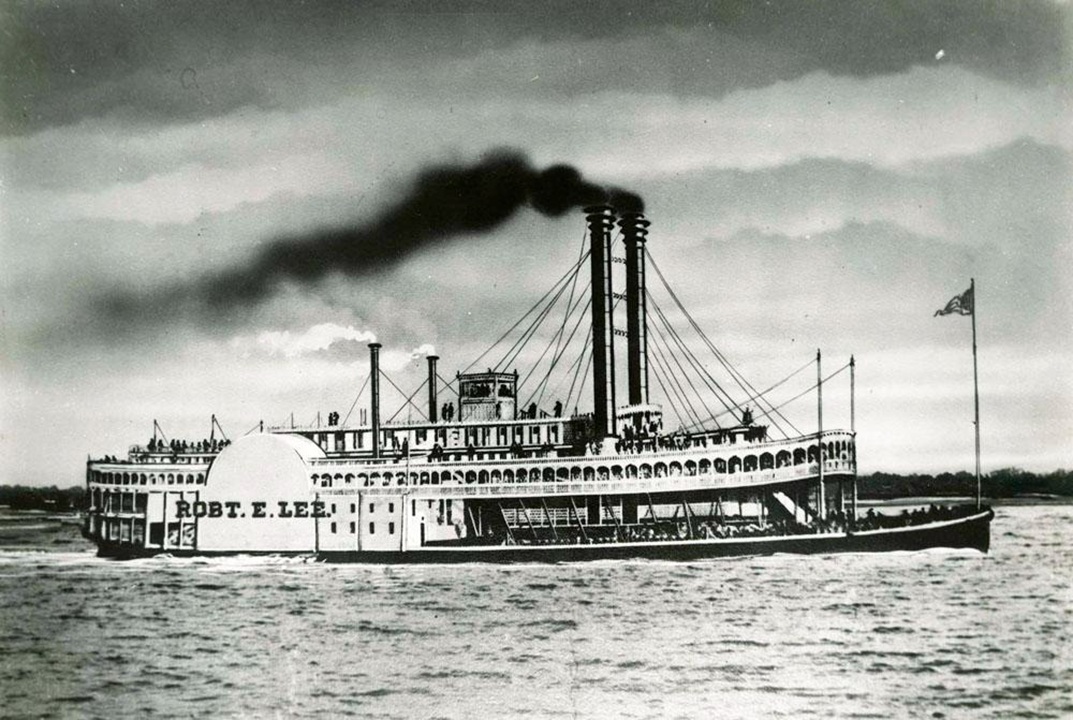

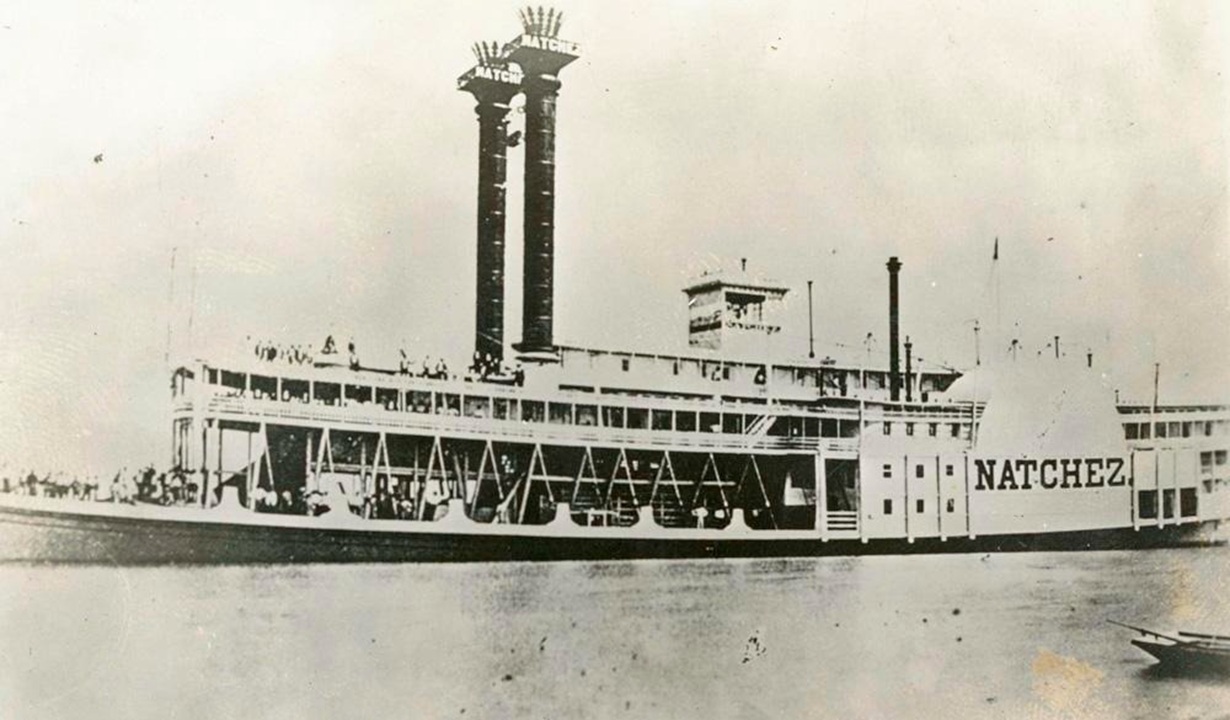

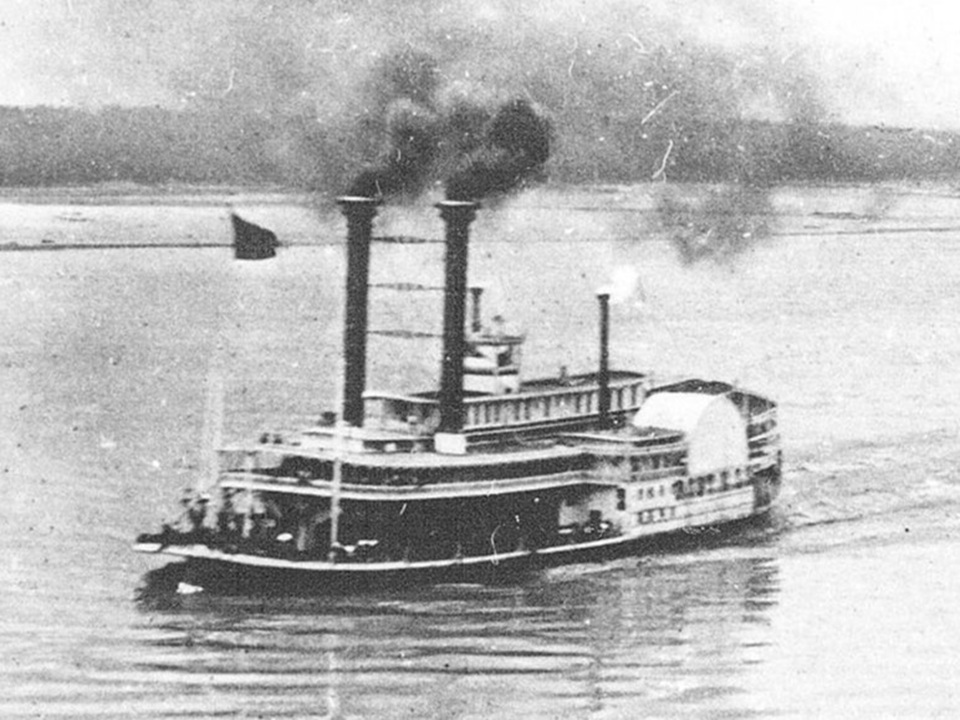

The boats of this race were the Cannon’s Robert E. Lee (above) and Leathers’ Natchez.

The Robert E. Lee was launched on the Ohio River in 1866 and was built to be the fastest and most luxurious thing on the Mississippi. The steamboat measured 285 feet long and 46 feet wide, with a pair of 38-foot by 17-foot paddlewheels. She was fed steam from eight 28-foot-long 110 PSI boilers. Its cylinders were 40 inches in diameter.

Meanwhile, the Natchez (above) was the sixth ship to bear the name, and it was built in 1869. She was slightly larger at 303 feet long and 46 feet wide, with a pair of 42-foot by 11-foot paddlewheels. She got her steam from eight 33-foot-long 160 PSI boilers and was driven by 36-inch cylinders.

The Natchez was already a famous boat because its sole purpose was to be even faster than the Robert E. Lee. The idea? Build a boat so good that the Natchez would rule the river. To the Natchez’s credit, it started racking up speed records once it was put into service. Technically, the Natchez was faster than the Robert E. Lee, but speed records are different than racing.

A 1,200-Mile Sprint

The race was an epic one, too. The boats would depart New Orleans and steam full power straight to St. Louis, Missouri, 1,200 miles up the mighty Mississippi. The men scheduled the race to start on June 30, 1870, and it quickly made national news. Reportedly, countless towns along the Mississippi pretty much put everything on pause just to watch the race, and gamblers from all over America placed huge bets on the race. The New York Times claimed that, no doubt, some rich gamblers placed bets as high as $200,000. Steamboat race fever was back.

The book, All About History, claims that this great race was an equalizer of sorts. America had only just gotten through a bloody Civil War, and tensions were still high. Yet, at least for the week of the race, apparently, everyone gave their attention to the racing steamboats. As the book claims, everyone, regardless of whether they were white or black, or man or woman, had an opinion about the race and a favorite boat to win. From the book:

To those who merely looked on, a steamboat race was a spectacle without an equal. To the people of the lonely plantations on the reaches of the great river, the sight of a race was a fleeting glimpse of the intense life they might never live. To see a well-matched pair of crack steamboats tearing past, foam flying, flames spurting from the tops of blistered stacks, crews and passengers yelling — the man or woman or child of the backwoods who had seen this had a story to tell to grandchildren.

All About History also notes that there was some hope that the race would drive customers away from the railroads and back to steamboats.

Just before 5 in that late afternoon, the Robert E. Lee fired its gun and steamed past the start line at full speed, immediately taking the lead. The Natchez would steam out four minutes later. Reportedly, the Robert E. Lee was able to get the lead as Cannon’s crew arrived early and manned their stations, ready to get the jump on the Leathers crew.

The most often cited account of the race, which was published by the New Orleans Daily Picayune at the time, claimed that the Robert E. Lee was stripped of all unnecessary weight, carried no cargo, and had only 75 passengers. Famed steamboat captain and historian Frederick Way, Jr. allegedly disputed this claim by citing Johnny Farrell, who was the second engineer aboard the Natchez. Farrell claimed that both boats actually had minimal prep. It’s believed that the Natchez took on 90 passengers and a full load of cargo, as Leathers was so confident in his boat that he ran the race like it was just a normal run up the Mississippi.

Whichever version of the story is true, it sort of doesn’t really matter. The boats would steam through the night, with the Natchez following right behind the Robert E. Lee. Reportedly, crowds cheered these boats on even well past midnight.

Breaking Records

Unfortunately for Leathers, the great headway and lead of the Robert E. Lee meant that the speed records that he had set in the past were getting beaten. On July 1, the Robert E. Lee raced through Natchez, Mississippi, beating a New Orleans to Natchez record that Leathers set 14 years prior by nineteen minutes. While Cannon might have broken Leathers’ record, Leathers was only 8 minutes behind with the Natchez still giving chase.

It’s reported that, during this race, the extremely talented crews of both boats worked to make sure their steamers had maximum power without exploding. After all, these vessels needed to work at full speed for days. There were now safety regulations also in place to try to reduce steamboat fatalities. Unfortunately for Leathers, the Natchez wasn’t as reliable as the Robert E. Lee. The Natchez was slowed down by mechanical issues and was then slowed down further by the boat getting grounded multiple times. By the time the Robert E. Lee steamed through a fireworks display in Memphis, Tennessee, the Natchez was a full hour behind.

The Robert E. Lee then steamed through Cairo, Illinois only three days and one hour after it left New Orleans, setting a new record. By this point, the Natchez was nearly a full day behind. Ultimately, fog would end up sidelining the Natchez for hours, and the Robert E. Lee would arrive in St. Louis only three days, 18 hours, and 14 minutes after it left New Orleans, beating the record that the Natchez set only two weeks before by three hours and 44 minutes.

Curiously, the Natchez arrived in St. Louis only six and a half hours behind the Robert E. Lee, which is impressive given the fact that the boat was about a day behind. Cannon was given a hero’s welcome in St. Louis, and the crowd was reportedly so huge that police couldn’t even keep onlookers away. Amazingly, the crowd then stuck around and gave Leathers the same welcome when he arrived. Everyone was just so stoked about this race that it seemed only the people who bet money truly cared about who got there first. In the end, the Robert E. Lee averaged 13.5 mph while the Natchez averaged 12.5 mph. The boats were generally able to hit 15 mph and 16 mph, respectively.

After the race, Leathers reportedly tried to argue that, after factoring in the groundings, having to stop for repairs, and stopping to offload passengers, his boat was actually much faster. I could see that argument. I mean, his boat did mostly make up a time deficit of nearly a whole day, and that’s while making every single passenger stop, which the Robert E. Lee didn’t do. Technically, the Natchez was still the faster boat. But, Leathers ultimately conceded.

Trains Still Won, Anyway

While the Great Mississippi Steamboat Race, as it was advertised, captivated the nation, it would not save the steamboat from becoming an artifact of the past. Trains would become the vehicle of choice for transporting cargo and people, and then the automobile and the airplane would follow soon after. Cargo is still floated up and down rivers today, but the era of the steamboat has been over for a very long time.

Amazingly, steamboats are still raced today, but not in nearly as wild competitions. During the Kentucky Derby Festival each year, a pair of steamboats takes part in a two-hour race. It’s just like the old times, but without all of the explosions. The Mary M. Miller won the race last year, and the next race is scheduled to run on April 29, 2026.

There is a sort of joke in the car community that gearheads will race anything from shopping carts to forklifts, if given the chance. There’s something a bit hilarious and absurd about racing vehicles that, on the low end, went only 5 mph, and in the late 1870s, went a speedy 15 mph. I could only imagine what it looked like to see a steamboat with smoke and sparks billowing out of its stacks, but passing by the shore at slightly faster than walking speed. It also sort of blows my mind that people actively sought out these races despite the fact that taking boiler plate to the face wasn’t just possible, but likely. But I suppose that could be an example of how it was a different era.

Top graphic: Library of Congress

Mercedes does it again. Stuck in an airport lounge and just got transported away for 10 minutes. Superb article, as usual!

The closest I ever got to a steamboat ride was at Disneyland.