Everything starts somewhere. Don’t believe me? Look at your very own life, former baby! See what I mean? And you know what? The company that makes both the Altima and the Pao, Nissan, got its start somewhere as well. Nissan got its start as Datsun, as you may know, way back in 1914, and that early period of Datsun/Nissan is an interesting one, and one that I don’t think gets that much attention here in the West. But it should! That’s part of why I was so excited to drive this little 1938 Datsun 17. The other part is just because it’s just a weirdly friendly and appealing little car.

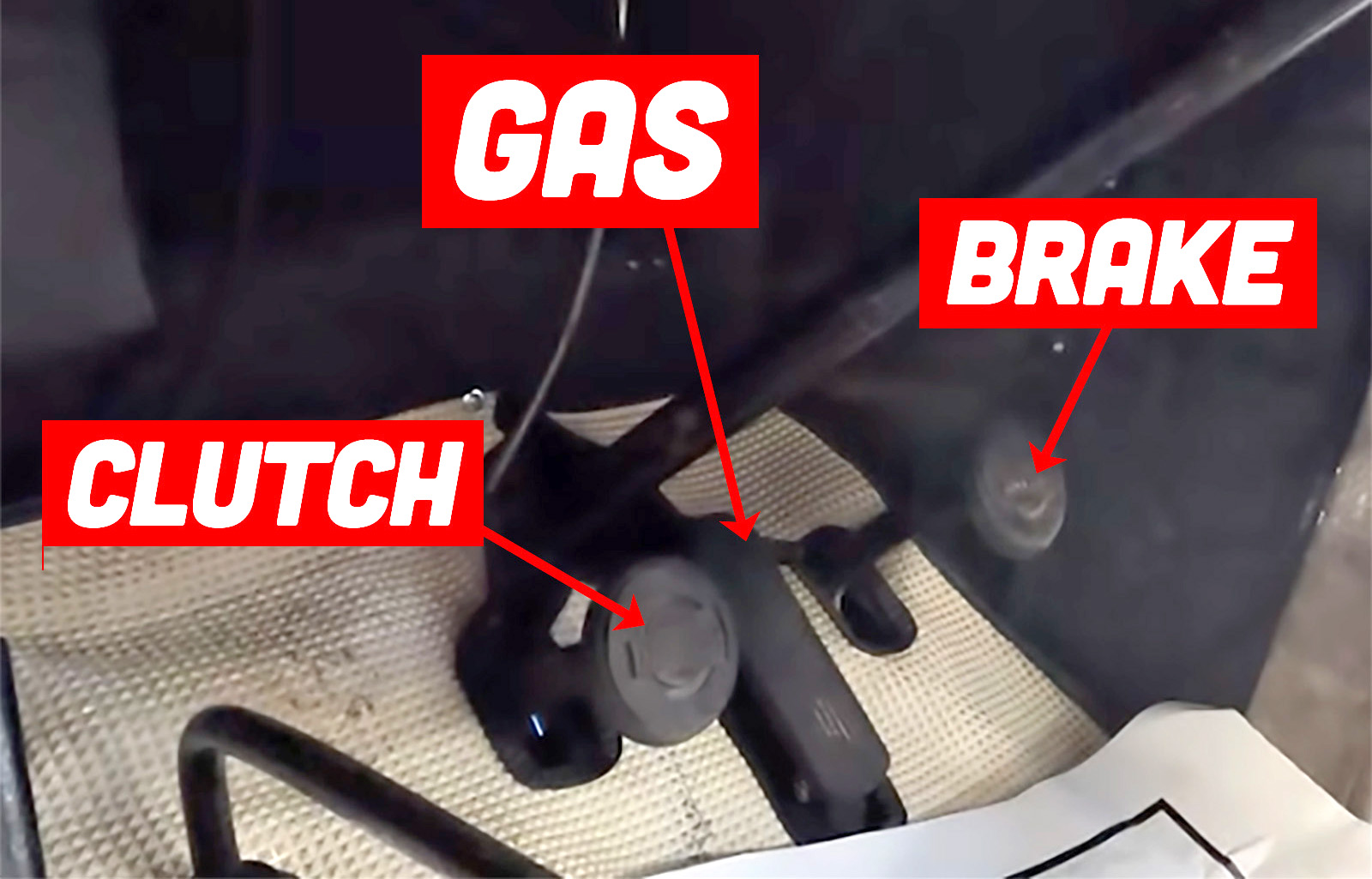

It’s also a very tricky car to drive because the pedals aren’t in the order you’d expect. Have you ever driven a car with pedals not where your feet expect them? It’s pretty exciting, in that I-might-lurch-into-a-hydrant kind of excitement.

I should mention that I got access to this delightful little car thanks to our pal Gary Duncan, who has a massive collection of incredible JDM (and other) cars. As always, thanks, Gary!

Here, you can watch the whole thing right here, right now, if you like:

I promised in the headline that I’ll reveal where both the Datsun and Nissan names come from, and I don’t want to be accused of being a liar (despite what my old shop teacher claims) so let’s dig into that. This will also give us a nice bit of history about the company!

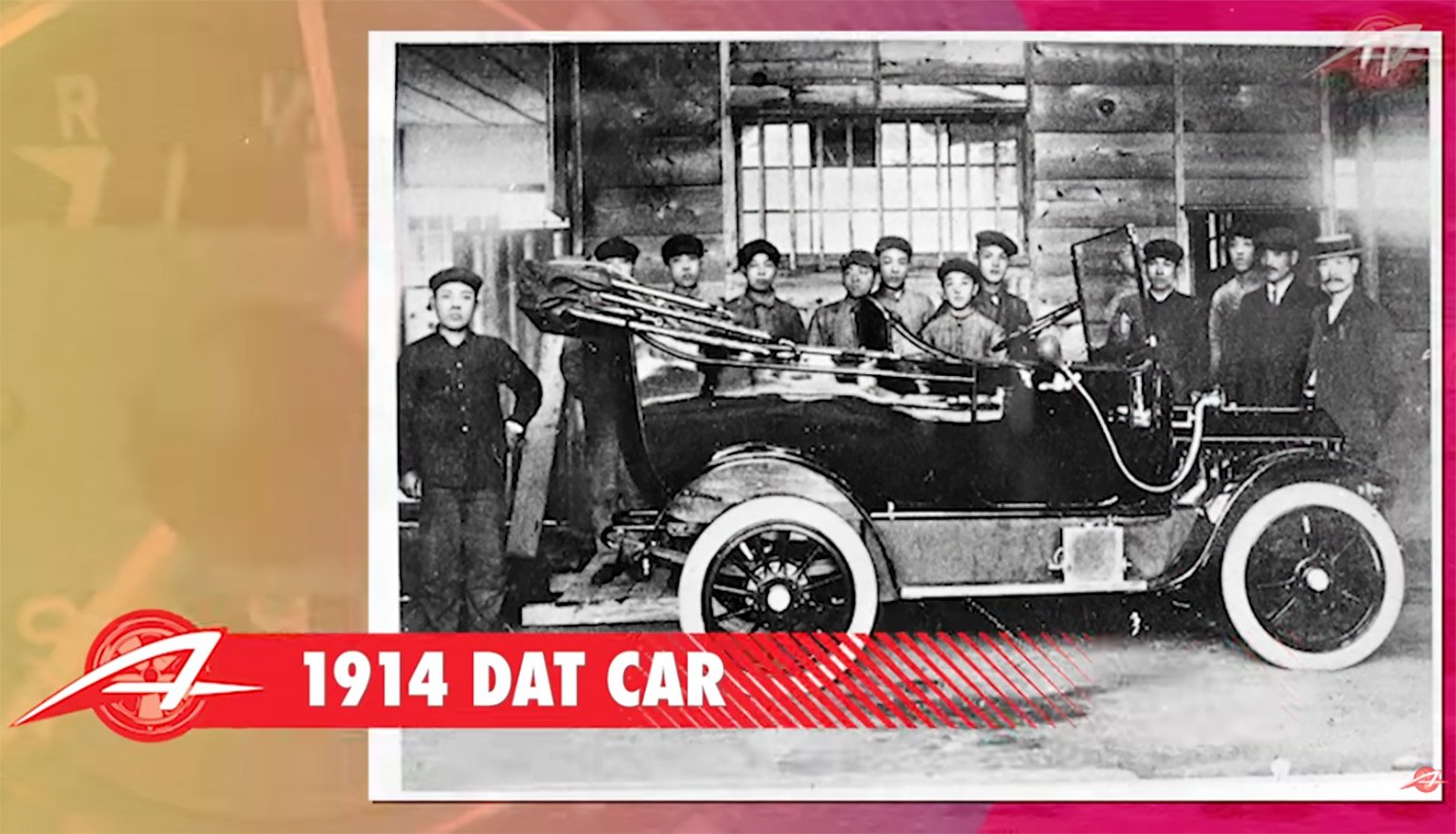

Everything starts with a company called Kaishinsha Motorcar Works (快進自動車工場, Kaishin Jidōsha Kōjō). This company was founded by three men, Kenjiro Den, Rokuro Aoyama, and Meitaro Takeuchi. Look at the first letters of their last names:

Clever readers have likely already deduced that those letters spell DAT, and the first car the company built, in 1914, was known as DAT:

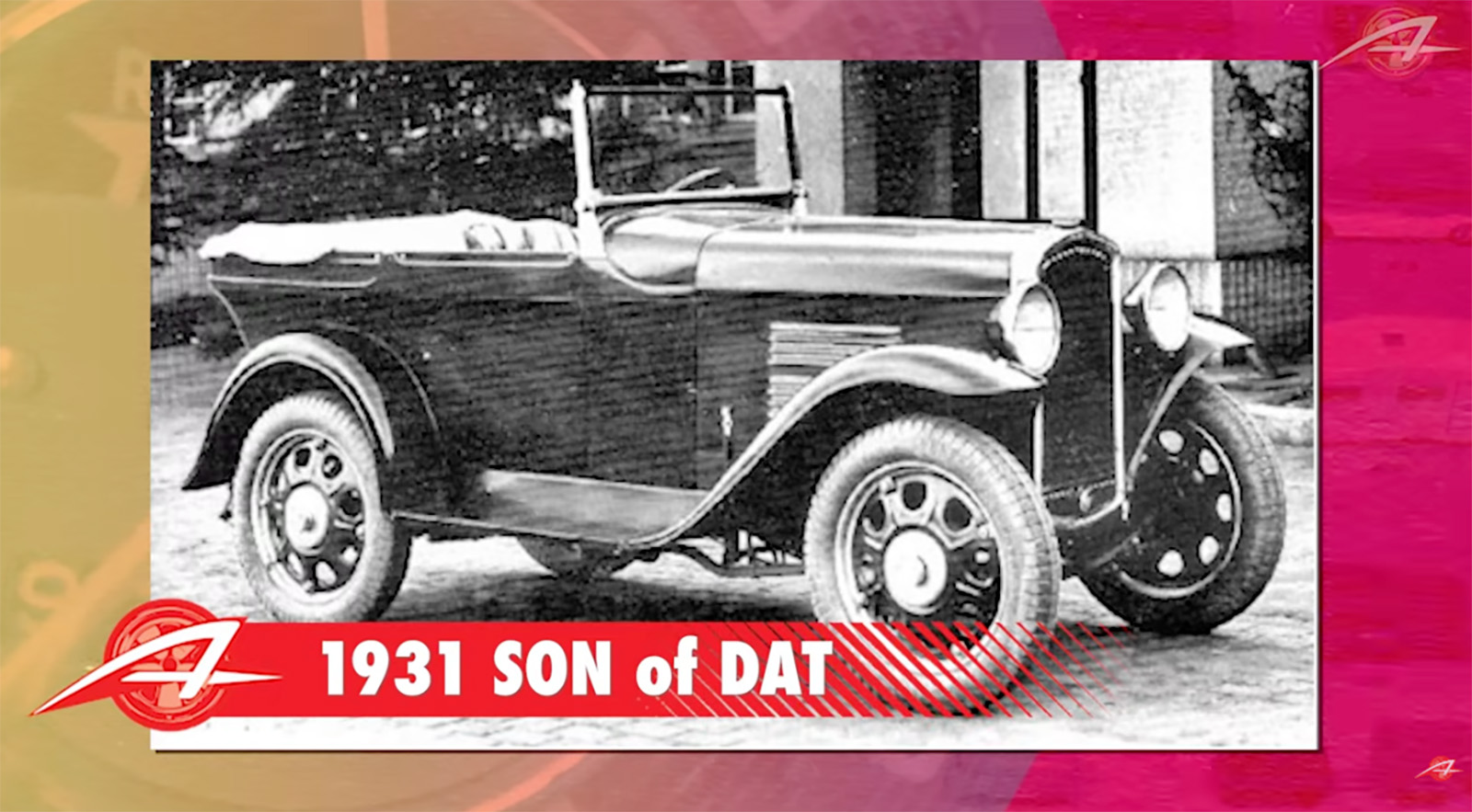

They later built a follow up to this car, a smaller one designed to be cheaper and to fit under a then-new (1930) Japanese ministerial legislation stating that cars with under 500cc engines could be driven sans-license. This car was the “son” of DAT, so it made sense to call it a Datson:

The only problem is that in Japanese, the word “son” can mean “loss” which is a bummer for a car, or, really, any consumer good. So, the “son” was changed to “sun” as in Land of the Rising, and the new name became Datsun! Oh, and, as a bonus, the name DAT is pronounced in Japanese as datto, which means to dash off like a rabbit, a pretty evocative name for a car. That’s why many early Datsuns had a little stylized leaping rabbit hood ornament:

Oh, and as far as the “Nissan” name goes, it has a different source. A holding company was formed in 1928 for Datsun, called Nihon Sangyo (日本産業 Japan Industries or Nihon Industries). If you make a contracted portmanteau of Nihon Sangyo, you get NiSan, and then if you throw in an extra S for luck, boom, there’s Nissan. What a generic name! It’s be like if Ford was called Amind (from American Industries) or something.

Datsun kept revising and improving their small cars over the years; The initial Datsun from 1931 was known as the Datsun 10. Then there was, predictably an 11, and then in 1933 a 12, which bumped engine displacement up to 733cc. Production of these early cars was very limited, as the company didn’t get a true integrated assembly line until 1935.

The progress over time from the 10 to the 17 was very incremental and gradual; there are those who claim this line of early Datsuns were copies of the famous Austin 7, but I don’t think that’s actually the case. There’d be no shame in it if so, as many notable carmakers got their start building Austin 7s, like BMW and, indirectly Jeep. But I think the Datsun was more inspired by the Seven than being an actual copy.

They are quite similar, but I think we’re seeing more convergent evolution than an actual duplication.

Driving this little Datsun was quite an experience; as I mentioned, the pedal layout is, to modern legs, maddening, with the throttle in the middle, sandwiched by the clutch on the left and the brake on the right.

When you drive it, at least at first, all of your muscle memory and reactions will be wrong. Luckily, power is so minimal that you’re unlikely to get yourself into real trouble. The shifter is an absurdly long and spindly metal pole with more kinks in it than a swing club. It’s comfortable, though, and once you get used to the quirks, pretty easy to drive.

This ’38 model is sort of the last of its kind; after this one, production shifted to wartime truck production to supply the war with China, which would then blur into WWII.

I think what I found most fascinating about this humble little car, aside from the cable-operated semaphore turn indicators, is how you can sort of feel the start of the mighty Japanese car industry here, despite the car’s relative crudeness and simplicity. It’s all built so well, so carefully, and you can sense that there’s great competency and capability behind it, just waiting to be unleashed on the world.

What a fascinating little car!

mis-placed pedals… ever speed shift an old vw auto stick shift and stomped down on the clutch pedal out of force of habit? have you ever, bunkie?

“Americans don’t like the name Nissan. We need a new name!”

“When?”

“By tomorrow!”

“Dat soon?”

Too bad The Autopian pays by the word, based on the average length of a story.

Gene Wilder: “DAT Car!”

Marty Feldman: “Dat house. Dat tree.”

“Is dis ur car?”

“Nah, it’s dat one over dere.”

I had a 1979 Datsun 210, a big step up from a Ford Pinto with the exploding gas tank option. BTW, it was pronounced DOT-sun. Here’s an old commercial.

I have also driven a car with the pedals in the wrong place. I’ve driven a Model T. Which also happens to have the shifter (a couple of the pedals) and throttle (behind the steering wheel) in the wrong place as well.

The center throttle layout, though, is juuuuust similar enough to a normal car to be absolutely maddening.

Sounds like a tractor layout.

It pretty much is.

“more kinks in it than a swing club”

This took me a second as I tried to figure out why a golf club would be bent at all….

Thanks for not letting me miss that – my brain just thought “golf reference” and moved on to the next shiny object.

You must have been pretty lucky to not have had a bad day on the course ha! Seen several people bend clubs over legs, around trees or attack the golf carts. Pretty hilarious

The Nissan name origin is about as generic as SAAB! Svenska Aeroplan Aktiebolaget (AB), or Swedish Airplane Inc.

Or FIAT, or any other number of acronyms that state the obvious. Nissan just sounds more meaningful somehow.

Simca is my fave: Société Industrielle de Mécanique et Carrosserie Automobile; “Mechanical and Automotive Body Manufacturing Company” – such a lot of words to say practically nothing.