You could argue that an “electric car company” is not something that needs to exist, and that car companies should simply be Car Companies, not tied to any particular powertrain. But electric car companies do exist in the U.S. in the form of Tesla, Rivian, Lucid, Polestar, and Slate, and the reason why is pretty obvious: “Electric” was the hottest new term of the last two decades, and a necessary one to raise enough capital to get a new company off the ground. Pitching a hybrid car company to a group of investors would have been as fruitful as the messages I used to send on dating apps. But now it’s 2025, and that hot “electric” term is now lukewarm at best.

A few months ago, I was at a Rivian event in which I asked a representative if the company would ever offer a gasoline range extender. The answer was an emphatic “no.” I asked the same question at a Lucid event and received the same answer. “The future is electric,” is the refrain I typically get from folks when I ask this question. To which I respond: “What’s your point?”

Telling me what the future is doesn’t seem particularly relevant. We could all be driving flying cars in the future, but if you started selling only flying cars today, you’d be a fool. This reminds me of 2022, when GM announced it would skip hybrids because the future is electric. More specifically, per the Detroit Free Press, Mary Barra said:

“GM has more than 25 years of electrification experience including with the plug-in vehicles like the Chevy Volt …From that experience, our vision is for an all-electric future. Our strategy is focused on battery electric vehicles as they represent the best solution and advance our vision for an all-electric future.”

I remember thinking upon reading that: “Sure, the future may be electric, but you’re selling cars now, in the future’s past. Right now, people want hybrids.” As expected, GM backtracked on its plan to offer only EVs and to skip hybrids, and is now going heavy into the hybrid game (while still offering a solid array of EVs).

Too Many Companies Are Splitting Too Small A Slice

The future is electric, but today is not electric. Toyota understood this because they understand consumers, though they got dragged by journalists for not going all-in on the new hotness. But sales numbers bear out that hybrids are the answer, and what’s more, automakers like Rivian and Lucid losing absolute metric crap-tons of money on electric vehicles — and other car companies like Ford deciding it’s worth losing $20 billion to cut many of its electric vehicle programs altogether — goes to show that the market just isn’t there for fully electric cars.

Of course, there’s Tesla, a company that managed something amazing. Lightning in a bottle, you might call it. It was an American company that came out of nowhere, developed its own charging infrastructure, created electric cars that were generations better than anything up to that point, and offered the cars at a rather competitive price. They also had a larger-than-life CEO who was admired by most of the world at the time, and also, they made loads of money by selling ZEV credits to automakers running afoul of CO2 compliance. That credit system is likely gone in the United States, thanks to the new presidential administration.

I get the impression that many companies saw Tesla’s success as proof that a sustainable EV company can exist. But in my eyes, to try to replicate Tesla’s model is silly. Tesla is one-of-one. An outlier. I tweeted this thought over a year ago, suggesting that EV companies should hybridize ASAP:

My suggestions to EV-only automakers: 1. Be careful looking at Tesla and thinking “I want those sales numbers.” You are not Tesla. Don’t try to be Tesla. Tesla is an anomaly. And 2. Get on the range extender bandwagon as soon as possible. Transition back to BEV-only later. https://t.co/1b7H2jmfN0

— David Tracy (@davidntracy) October 25, 2024

You know who replied to that tweet? None other than Ford’s own Jim Farley, CEO:

Now it’s nearly 14 months later, and Ford announced that its departing fully-electric F-150 Lighting is being replaced by a range-extended F-150 Lightning.

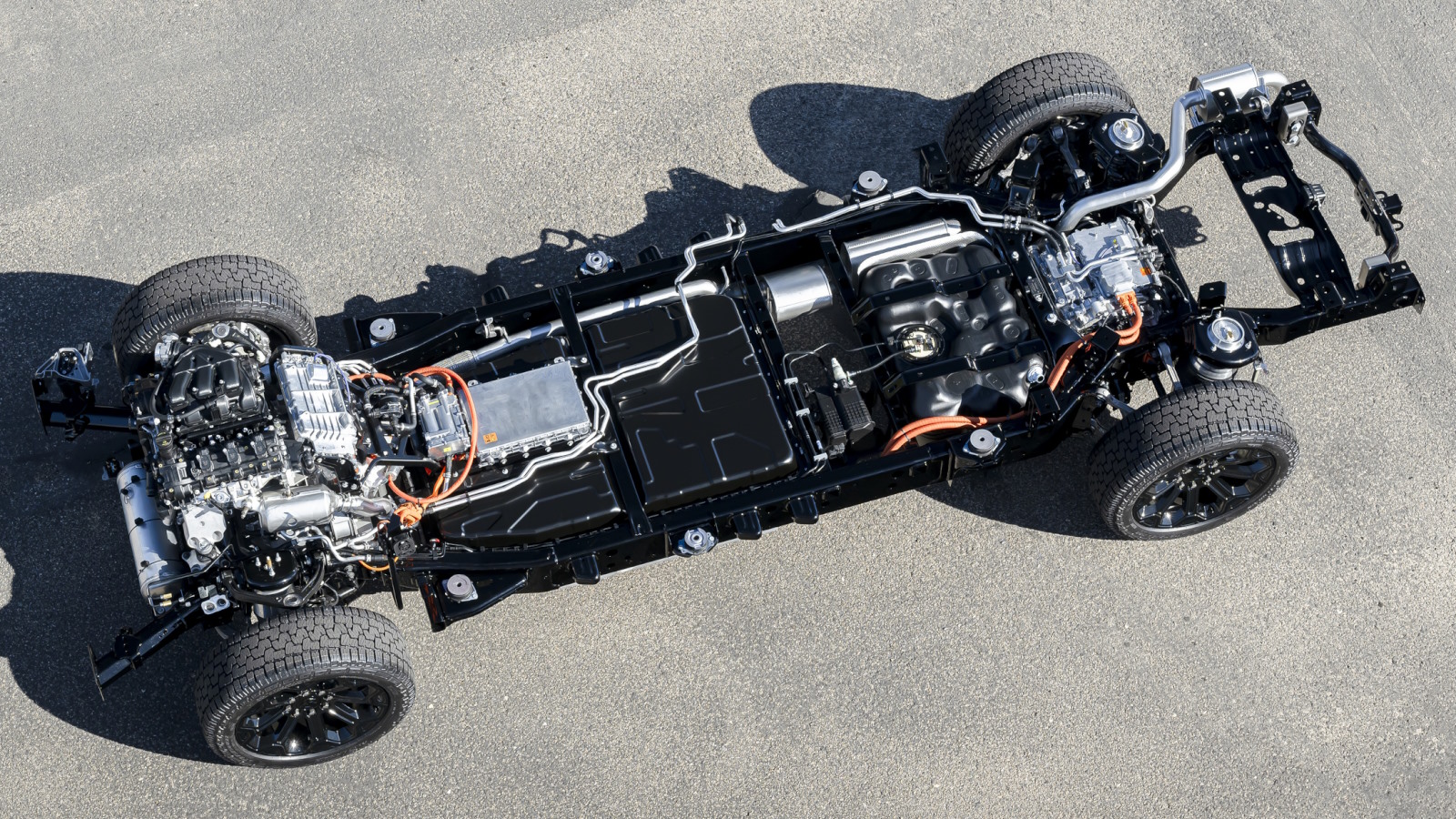

Ford Will Add A Gas Engine To The F-150 Lightning To Create A 700-Mile EREV

Naturally, EV-diehards are not thrilled:

This is what happens when you make sh*t products. This has nothing to do with making EV’s; this has everything to do with making bad EV’s. https://t.co/f3kxBlR6Ul

— phil beisel (@pbeisel) December 16, 2025

Hybrids are not the answer Jim

The future is all-electric and autonomous

You should’ve taken Elon’s offer to license Tesla FSD years ago…

Not looking good for Ford https://t.co/vPdl8fBtc5

— Dalton Brewer (@daltonbrewer) December 16, 2025

This going EREV will almost certainly be better for the environment than the BEV.

100K people trading their 15 MPG F-150 for an EREV truck has more value than 25K people trading their Tesla for a BEV truck.

— David Tracy (@davidntracy) December 16, 2025

You can see my opinion on the matter in the reply above.

This seems like a smart move on Ford’s part. The truth is that fully-electric pickup trucks make little sense for the mass market, and if you don’t believe me, just listen to what the former CEO of Lucid (an electric car company that refuses to offer gasoline engines) told me when I interviewed him last year:

“But let me tell you the reality is, and it’s me saying this, that it is not possible today with today’s technology to make an affordable pickup truck with anything [other] than internal combustion.”

This is just reality, which is where major corporations have to live.

With Fully Electric Vehicles, America’s Love For Big Cars Gets Expensive

America loves large cars, and large cars typically have what’s called in the industry “a high Vehicle Demand Energy” (VDE). This is the energy needed to move the vehicles down the road, and though it can be affected by powertrain (because, for example, a gas engine requires more cooling, which can lead to more drag; an electric vehicle is heavier, which can lead to more rolling resistance, etc.), this is more about the vehicle in which the powertrain is placed than the powertrain itself.

America’s taste for large vehicles means we tend to drive cars that require lots of energy just to go down the road, and if that vehicle is, for example, a pickup truck (like a Chevy Silverado EV) or SUV (like a Rivian R1S), you’re going to need a massive battery to achieve the range that the average American wants. Both the Silverado EV and the Rivian R1S offer batteries over 140 kWh, with the former offering one over 200 kWh.

Add a big trailer to those vehicles, and even those giant batteries won’t be enough to overcome not only range issues, but recharging issues, as infrastructure still isn’t good enough, and pull-through chargers for trailer-pulling pickups just aren’t very common even in 2025. When it comes to towing, EVs are simply the wrong tool for the job, as I wrote last year.

With Lucid and Rivian losing billions of dollars annually as EV demand remains softer than expected (though we do have some early signs that Rivian is turning things around, with a few quarters of positive gross profits, though net profits remain elusive), there’s an obvious question worth asking: Should these companies build cars that appeal to more than just a small electric sliver of the American car market-pie?

Rivian thinks the upcoming R2 and R3x will be enough. I have no doubt that they’ll sell relatively well, but I do have doubt about whether they’ll bring Rivian to sustainable net profitability. After all, the world already has cool, small electric SUVs like the Hyundai Ioniq 5 and the Chevy Equinox EV. And sure, you could say the world has lots of great hybrids, but the sales figures are on a different level. With hybrids, there’s more than just a sliver of the American market “pie” to share.

EREVS Are A Compromise That Can Minimize The Most Important Compromise

America wants hybrids; when Scout offered its vehicles as fully-electric or range-extended hybrid models, the majority of pre-orders were for the hybrids. And for good reasons. Though some EV purists call hybrids “compromises,” in truth, every car is a compromise, and a hybrid’s main advantage is that it’s actually a compromise-minimizer. If you think about the compromises that actually matter in the car world, it’s not compromises to packaging or complexity or even vehicle performance — what matters, big picture, is minimizing compromises to the way a driver actually uses their vehicle, while keeping the biggest compromise — cost — down. And in this way, hybrids are less of a compromise than BEVs.

I live in California, where the infrastructure is better than pretty much anywhere stateside. Still, charging a BEV can be an inconvenience compared to filling up a gas car, and what’s more, it can actually cost as much or more. I’m not saying charging a car here is bad — if you leverage the right apps, and are smart about planning, you can really get a lot out of driving a BEV (and you can save money on driving) — but the compromise is nonzero. It’s not about charging infrastructure or charging times or poor towing range — more than anything, it’s about cost.

Americans want to drive big cars, and they want to be able to not have to worry about range anxiety. This RA term is one that lots of EV journalists have historically dismissed. “Nobody needs 300 miles of range. 100 is just fine!” many say. In fact, here’s a Facebook reply to our story on Ford ditching the BEV Lightning for an EREV:

The Lightning is an excellent vehicle that won’t sell because truck buyers think they’re going to tow a trailer 500 miles every weekend. They won’t, and the range of an Lightning would actually meet their needs 99% of the time, but people stupidly make buying decisions based on that remote possibility that they might need extra capability someday.

The Gas Generator Doesn’t Have To Be Great Or Expensive

Are EV Car Companies EV-First or Environment-First?

OK, So There Are Some Huge Branding Problems

One topic I cannot ignore is the branding of it all. If a company has built its identity on a powertrain, things get tricky if they want to offer a different one. Rivian is all-electric, anti-gas. Lucid is the same. Tesla is the same. Since their inception, they’ve been no-gas, all-electric companies, largely because none of these companies would exist otherwise. How, then, can you maintain brand integrity if you offer a gasoline range extender?

I Love EREVs, But Even They May Have A Hard Time Selling Over Gas Or Conventional Hybrid Cars

EV Car Companies Are In A Tricky Spot

For a more complete breakdown of Range Extended EVs’ benefits and drawbacks, see my three articles on the topic. Note: I am not an oracle, and many of you, dear readers, are geniuses, so I welcome your thoughts in the comments. Also, for the EV-purists who will inevitably be upset that I like something other than a pure BEV: I also love BEVs. In fact, I love them so much that I wrote positive reviews about the Cybertruck and Fisker Ocean. BEVs are an excellent option for folks who can charge at home/work, requiring less maintenance than an EREV. Neither BEVs nor EREVs are not the answer for everyone, but variety is key.

Top graphic images: Lucid; Rivian; Tesla; BMW

Having owned and dailied diesels, gassers, regular hybrids, hybrids with big batteries (like the Jeep Wrangler 4xe), EVs, and EREVs… the latter are by far the best of the pack today for me.

BMW’s i3 REx formula was fantastic, and I still don’t get how Honda hasn’t picked it up. They have all the things needed in-house even, with Honda scooters and cars being amongst the most reliable in history!

If today’s big battery challenges in both storage density and cost are resolved, then BEVs will come into prominence. The question appears to be ‘when’.

Fortunately, I can sit and wait, and will continue to drive my fairly efficient and reliable ICE wagon for another 2-4 years.

Hopefully by 2030, batteries will meet and be available to match all of today’s hype and promise of new chemistries and manufacturing methods.