The articulated bus, or bendy bus, is a wonderful piece of engineering. These buses manage to greatly increase passenger capacity while maintaining maneuverability. These buses are all over the world today, but there was a time when they were novel. America’s first articulated bus, the 1938 Twin Coach Super-Twin was a marvel. This bus, which, weirdly, only articulated in one direction, allowed the city of Baltimore to carry 56 people and was, allegedly, the largest passenger vehicle on the road.

So far as I can tell, the articulated bus has almost always been a part of bus history, and for good reason. A regular trolley bus or motor bus can become only so large before making it longer will impede its ability to drive around a city. Yet, transit systems want to be able for their buses to carry as many passengers as possible. One bus that fits more people can be cheaper to operate than two buses carrying the same number of people, especially after you account for maintenance, driver wages, and other costs.

Historically, the easiest solution to this problem has been to produce a bus in two halves and hitch the second half of the bus to the first half as an articulating trailer. One of the earliest articulated buses that I’ve found is this Dutch Ford Model T from the early 1920s. It is hard to say if this was the world’s first articulated bus, but it does confirm that the concept is at least a century old.

Sadly, I do not know any further details about this bus, and my deep searches have uncovered nothing. I do not like leaving a story untold, so if you could tell me more about this century-old articulated bus, I’d love to know!

Anyway, a lot of early high-capacity buses didn’t really integrate the halves, and instead, the extra passengers sat in a trailer. Take a look at this Officine Meccaniche bus truck from 1930:

While less common today, every once in a while, there is a new bus design that is unveiled that doesn’t have an articulating section, but a trailer. In 2022, Sono Motors announced solar-powered bus trailers that were slated to go into service in Munich.

Of course, I cannot talk about towed buses without talking about the very fun trailer bus. Those weirdos are little more than tarted-up semi-trailers with seats and windows. But they aren’t really articulated buses, so I will talk about those buses on a different day.

Articulated bus history starts getting really interesting in the late 1930s. Over in Italy, Alfa Romeo produced the pioneering 1937 Alfa Romeo 110 AM-Macchi. This bus, which Curbside Classic said carried up to 180 seated and standing passengers, had a novel way of articulation. Unlike today’s articulated buses, which articulate horizontally and vertically like a trailer, the Alfa Romeo had only vertical articulation. Having the center section articulate up allowed the bus to drive up grades without getting stuck.

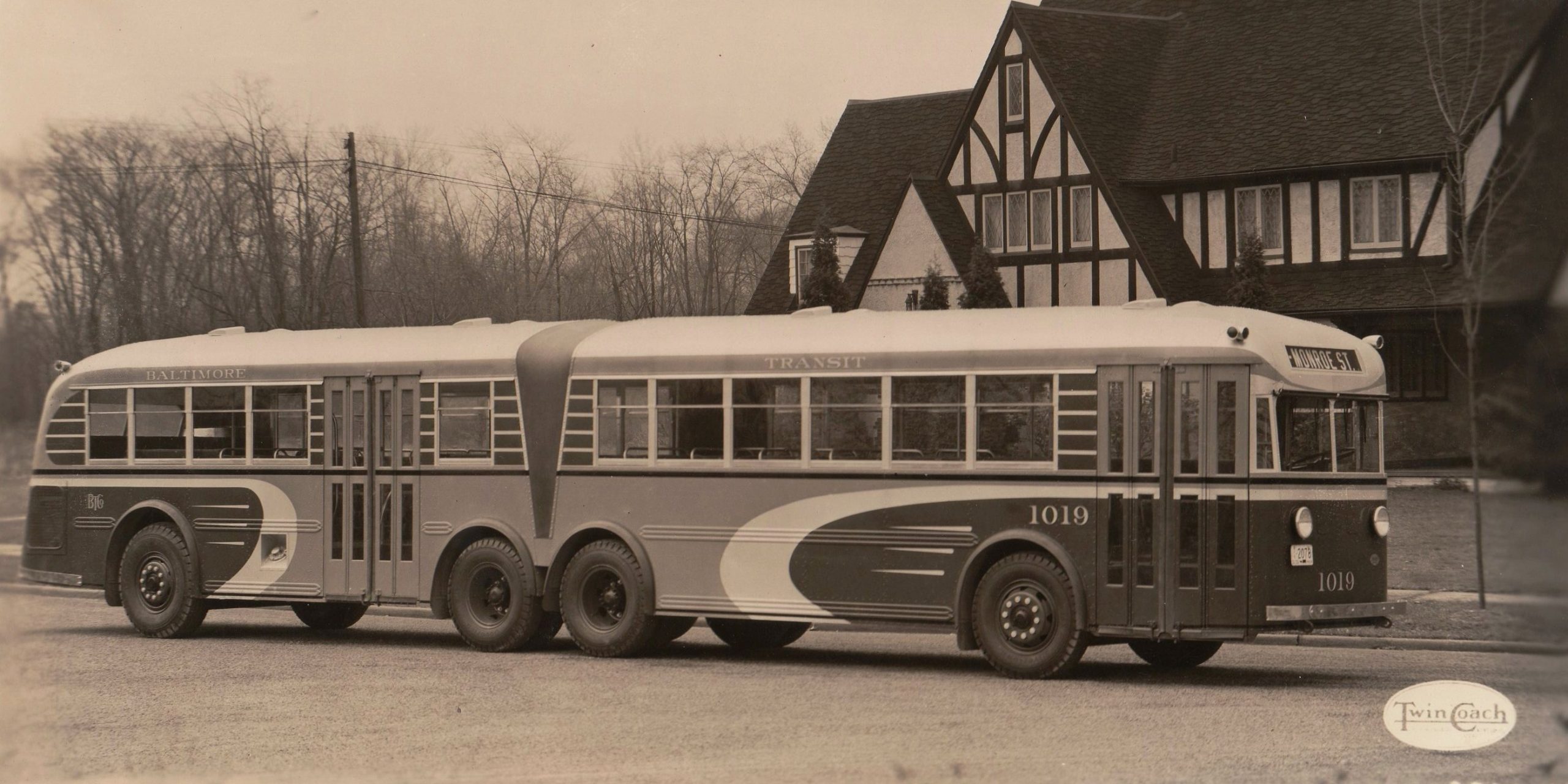

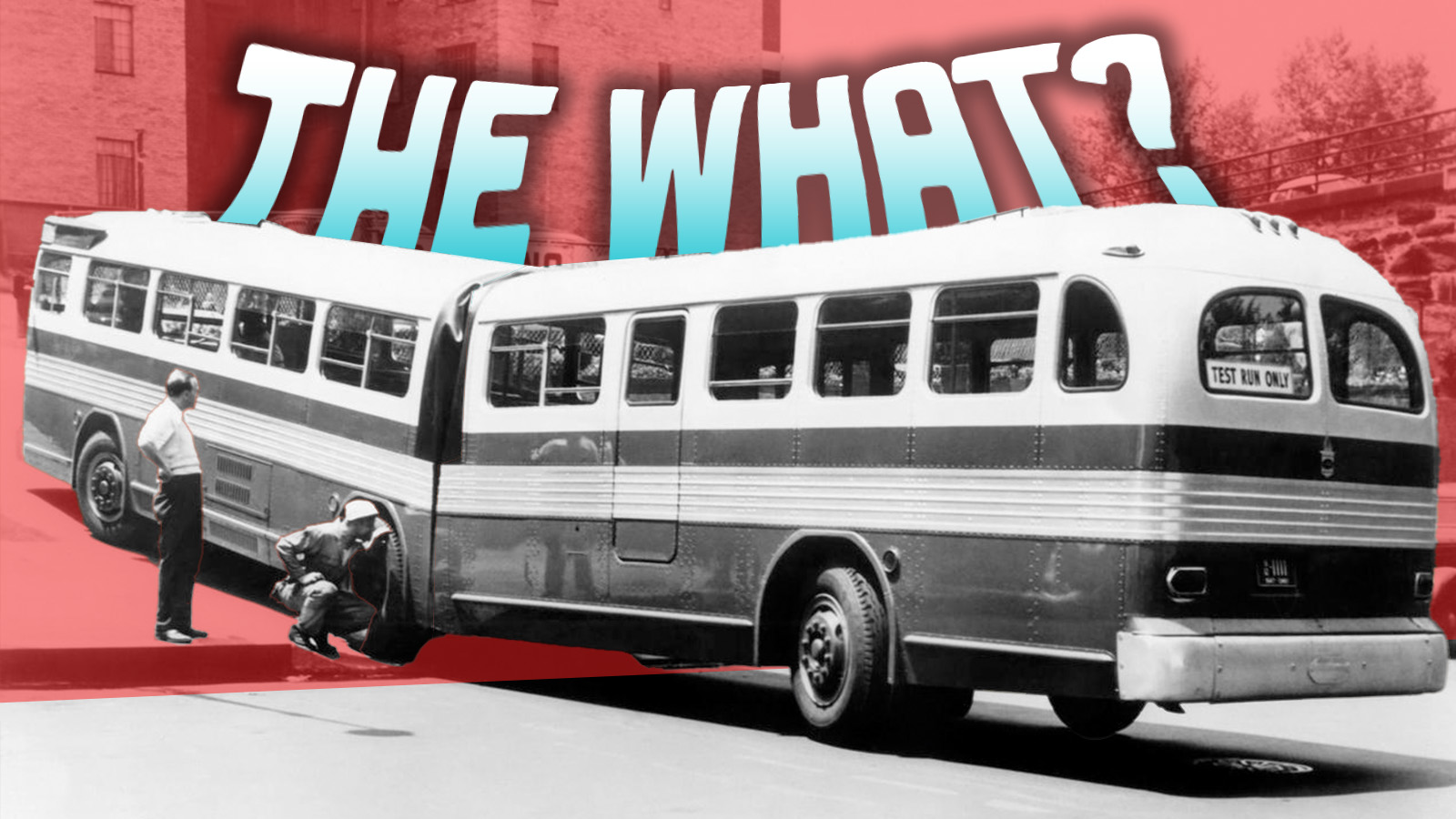

Now, you might be wondering how a bus that large was able to turn without a proper articulating section, and we’ll get to that in a bit. Only a year after Alfa Romeo put its new bus into service, the city of Baltimore got the bus that many bus historians consider to be America’s first articulated bus. That bus is this, the 1938 Twin Coach Super-Twin.

From A Bus Innovator

Twin Coach has somewhat frequently shown up in my recent retrospectives, and that’s because the company was known for honestly fascinating inventions. Twin Coach was the company that built a delivery truck that acted like a horse. From my previous story on Twin Coach:

Fageol Motors claim to fame was the 1922 Safety Coach, a vehicle sometimes credited as being the first purpose-built bus. Most buses in the early days of motoring were coach bodies on top of a truck chassis. The Fageol brothers saw this as a bad thing as trucks rode high and had particularly jarring suspensions. The Fageol had a custom frame and an aluminum body with a low floor, which was optimized for use as a bus. The Safety Coach had wide all-weather tires, air brakes, and interior heating via water heated by the engine.

The Safety Coach was so advanced for its day that some in the bus world claim that it changed the bus technology forever.

Eventually, Fageol Motor was sold to the American Car and Foundry Company of Ohio in 1925, but the Fageol brothers weren’t done yet. In 1927, William and Frank split off on their own adventure as they came up with their next big idea, the Twin Coach, and formed a company of the same name to produce it.

The Twin Coach was a leap forward for buses. The biggest calling to fame for the Twin Coach is what gave the company its name, and it was the inclusion of two engines. By duplicating engines, the Fageol brothers found that their motor bus had enough power to haul huge loads of people.

According to the Kent State University Library, the Twin Coach wasn’t just a practical bus; it was likely the first purpose-built city bus of any kind in America. There had been buses before the Twin Coach, of course, but they were passenger bodies on top of existing trucks.

Given that context, it’s not at all surprising that the next evolution of Twin Coach’s bus design would be to make an even bigger bus with higher capacity.

Bendy, But Only In One Way

In 1938, Twin Coach announced the Super-Twin, an aluminum-bodied bus that was so large that Twin Coach bragged it was the largest public transit vehicle that wasn’t a train. Amazingly, this is one of the rare times when I’m talking about a vintage vehicle and could find an intact press release. So, I’m going to pass the mic to Twin Coach:

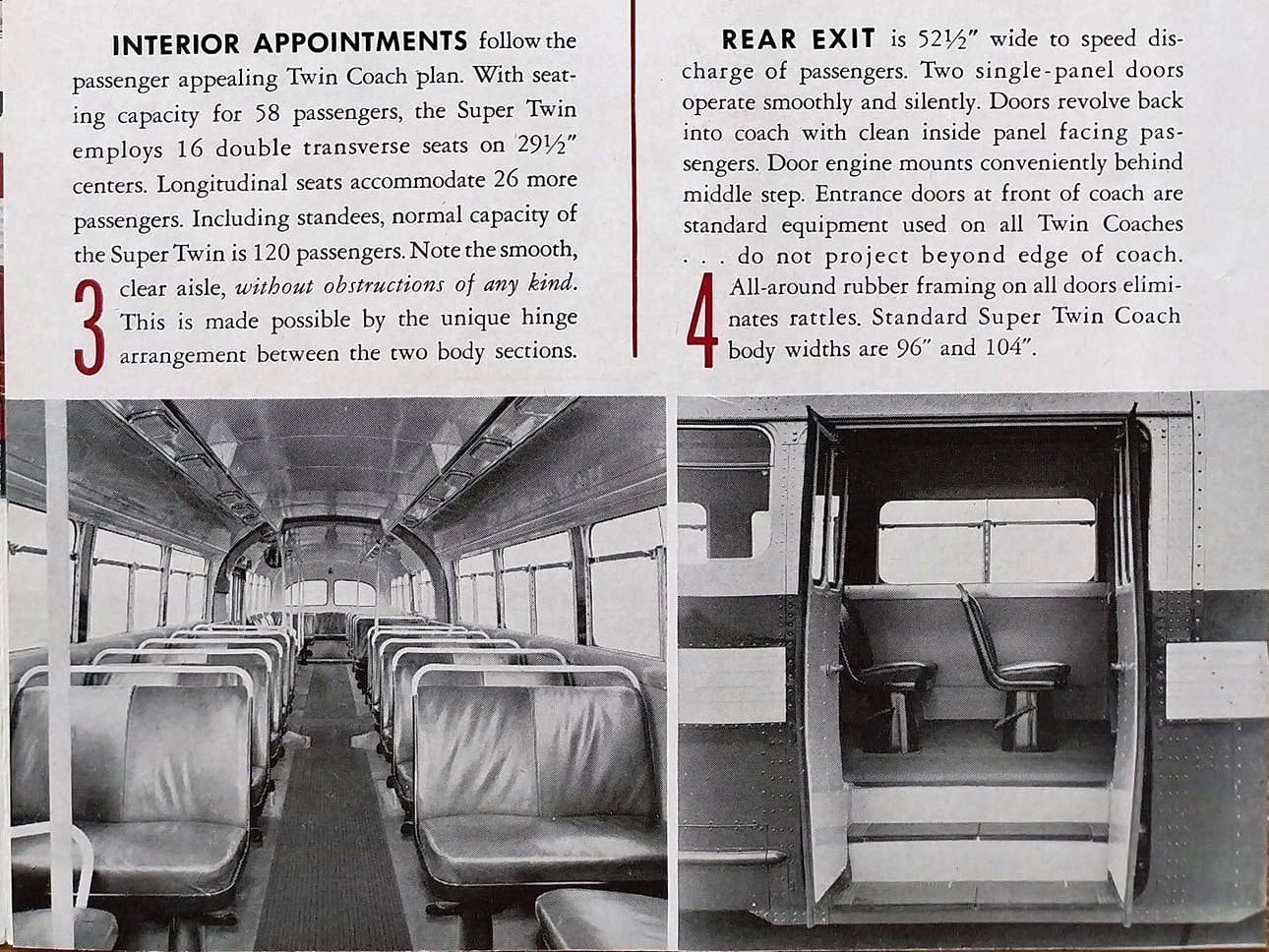

Kent, Ohio, June 15—The largest, capacity passenger vehicle for public carrier service, without the use of tracks, has been announced this month by Frank R. and William B. Fageol, President and Vice President, respectively, of the Twin Coach Company of this city. The vehicle seats 58 passengers on a single deck, and will transport readily, a passenger load of 120, including standees. The unit is designed to operate as an electric trolley coach or by Diesel-electric propulsion. The vehicle has four axles, eight wheels and bears its lead on 12 tires, the four center wheels taking dual rubber equipment. It weighs 27,500 pounds and is known as the Super-Twin.

“This unit will be capable of 50 miles per hour top speed, and, therefore, in regular schedule traffic, should have no difficulty in maintaining average schedule speed of 13 to 14 miles per hour, which is within one or two miles per hour of the average speed on principal subway lines.

“The new vehicle, on the fiftieth anniversary of the operation of electric trolley cars operating upon steel rails in the United States, immediately becomes a threat to continued large city street car operation, because it is the first seemingly practical unit created as a rubber tired public carrier capable of equaling the capacity of the largest city street cars, and at the same time, being able to turn on a radius no greater than the many 35-passenger gasoline coaches already in service in great numbers in this country. This is done by means of the synchronous steering of the front and rear wheels. The four wheels at the center of the job operate on the principle adapted to the many six-wheel vehicles already in use.

Twin Coach’s press release is long enough to make a public relations person at Toyota blush, so I will not post the whole thing here. Head over to Coachbuilt.com if you want to have some additional reading material.

The press release continues that the reason why the bus has two steering axles, one in front and one in the rear, is that the center section of the bus bends only vertically, not horizontally. Twin Coach’s logic here was that its 47-foot-long bus could easily traverse sharp changes in grade while remaining composed. By articulating the bus only in one dimension, Twin Coach said, the floor was entirely unimpeded. However, the twin-steering system ensured the bus could still effectively navigate bridges and tunnels. The “roof” of the articulating section was a thick rubber boot.

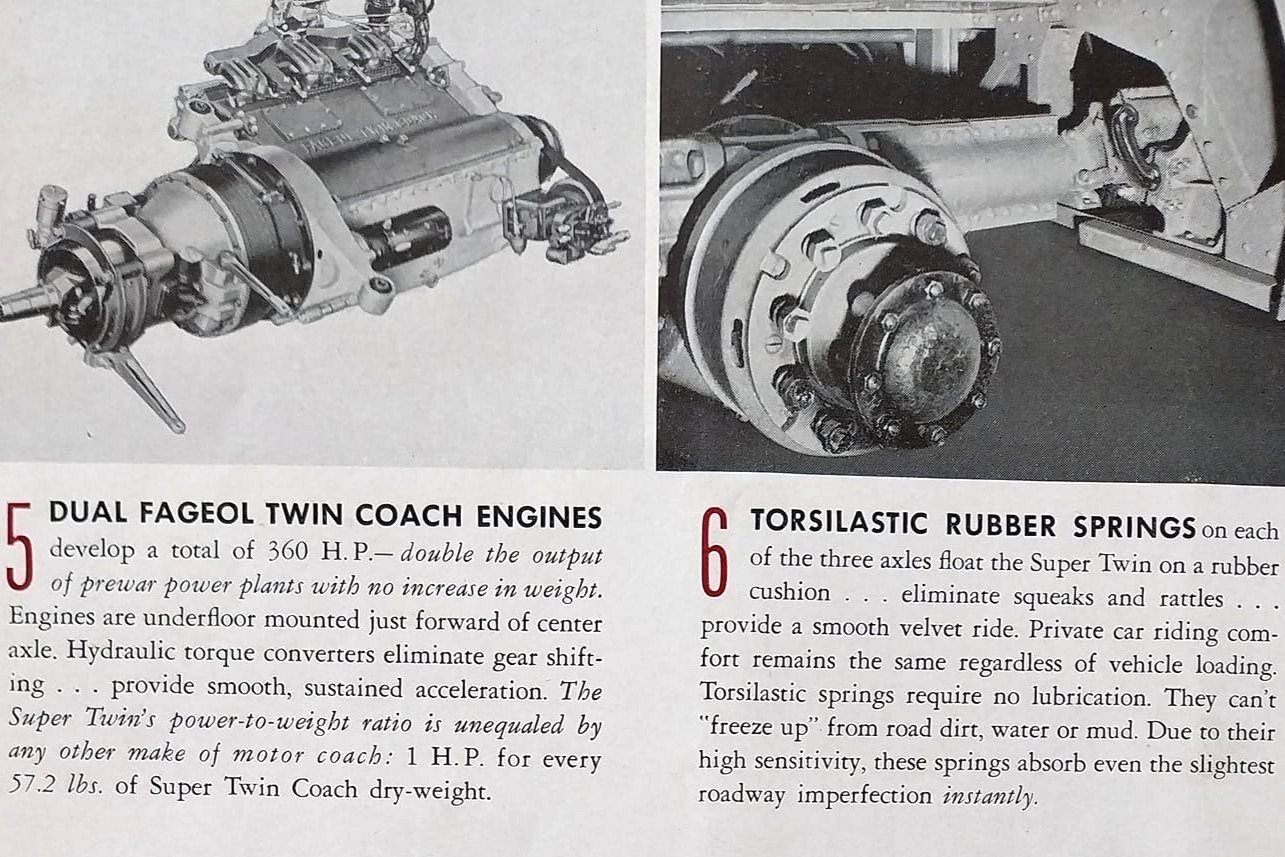

Perhaps more interesting than the articulating section is how the early Super-Twin was powered. Instead of using Twin Coach’s now trademark twin engines, the company instead opted to give the Super-Twin a pair of 125 HP electric motors, one in each half of the bus. These motors got juice from a 175 HP Hercules Diesel engine located in the middle of the bus. Twin Coach correctly pointed out that this made its Super-Twin a diesel-electric bus that worked just like, as Twin Coach says: “the Diesel-Electric Zephyr and other crack high speed transcontinental trains.” The press release further notes that the electrical equipment came courtesy of General Electric.

Later, the press release explains how the steering system works. The Twin Coach Super-Twin does not have power steering, and the rear wheels are steered through mechanical and air-based linkages to the front wheels, which are said to supplement the manual steering effort by the driver. Still, I cannot imagine the steering wheel of a Super-Twin being particularly easy to turn. At the very least, apparently, the bus was supposed to be as comfortable as a boat thanks to its cantilever spring suspension.

Like A Streetcar With Tires

What’s also really interesting is that the press release goes to great lengths to pitch the Super-Twin as both a replacement for streetcars and for other buses. In Twin Coach’s eye, instead of laying down expensive tracks for a streetcar, a cash-strapped 1930s city could just buy Twin Coach’s XL-sized bus and have a streetcar without the rails. From Ross Schram, Sales Manager for Twin Coach:

– According to the statistical record of TRANSIT JOURNAL, there were 75,777 urban public carrier vehicles in use December 31st, 1937, and 34,190 of these were street cars, mostly of the large capacity size, while many of the 25,614 motor coaches would have been purchased in larger capacity had there been an available unit.

– Modern trolley car road bed and track cost per mile is $100,000 for double tracks.

– The average expenditure per mile for trolley car road-way maintenance in American cities during normal times is 3½ cents per mile.

– The reduction of fuel cost over gasoline, if Diesel-Electric power plant is adopted.

– Tremendous sums and engineering efforts have been focused on the development of a new automatic transmission for large trackless gasoline units with questionable results thus far. In this new unit, as in other trolley coaches and Diesel Electric vehicles, there is immediately available the perfect answer to this quest.

– The large capacity rubber tired trackless ‘street car’ of this type is no longer tied to a strip in the center of the street, and thus traffic weaving, the greatest of all street hazards, should be reduced to a minimum. Recent studies reported by the Director of the American Transit Association show that considering the full capacity of a single traffic lane as 100%, a second lane, where channelized traffic is not enforced is actually only 78% efficient; that in the third lane without channelized enforcement the efficiency is only 56% compared with the first lane. Thus is statistically illustrated the waste of street space caused in traffic in our large cities where automotive traffic is weaving in and out between street cars. Of course, it is impossible to furnish accurate figures on the increased safety if all public carrier passengers were enabled to load and unload from a large capacity public carrier operating adjacent to the curb, but such protection would tremendously reduce deaths and injuries in the street.”

Twin Coach calling the Super-Twin America’s largest “public carrier service” vehicle is an important distinction. There were longer and heavier trucks on the road back then. Likewise, there had been some bigger private buses as well. Twin Coach’s bragging rights wouldn’t last long, however. In 1942, Santa Fe Trailways introduced the ‘Victory Liner,’ a double-decker bus so long that it had an articulating engine compartment. Yeah, you read that right. That’ll be a story for another day.

According to the Maryland Transit Administration, the Baltimore Transit Company commissioned the extra-large bus, and the Super-Twin had seating for 58 people or 120 people with standing passengers. The cost to the city of Baltimore was $17,088.70, or about $389,882.30 in 2025 money. The Maryland Transit Administration said that the bus, which it liked for its ability to climb grades, was affectionately nicknamed the “Queen Mary” by riders. However, the transit system also notes that the bus was a lot to handle.

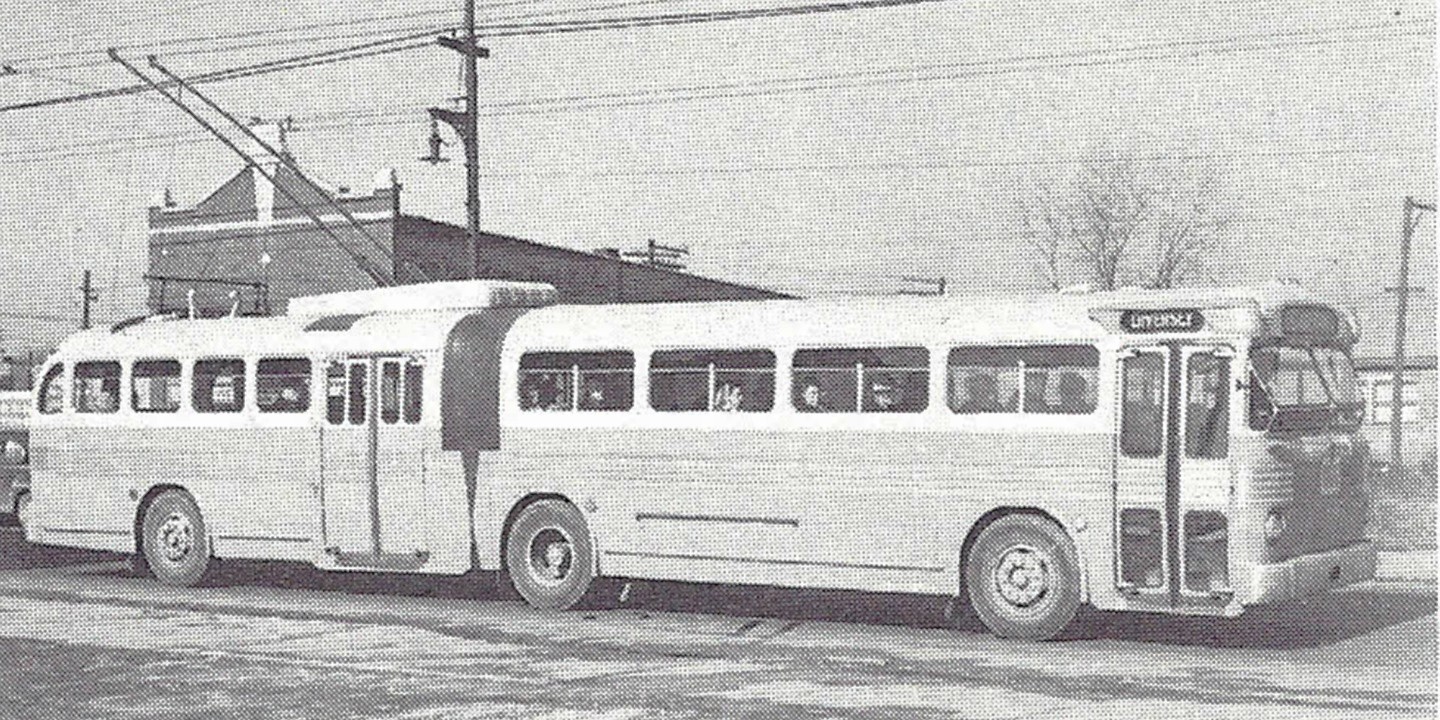

According to a Twin Coach brochure, another Super-Twin had been built and was in service around Cleveland, Ohio. A third Super-Twin was built and operated in Washington state.

Twin Coach built a fourth, updated Super-Twin in 1946 after World War II, and that bus did away with the funky diesel-electric technology for Twin Coach’s twin gasoline engine setup, making 360 HP. In 1948, that second Super-Twin was converted into an electric trolley bus and then carried passengers for the Chicago Transit Authority. According to a CTA document that I found, Chicago’s Super-Twin, No. 999, which was later renumbered to 9763, had seating for 58 people, or 18 more people than the typical bus of the era. As an electric bus, it has one WH 1442 electric motor, Electro Cam controls, and weighs 22,000 pounds.

The Chicago Transit Authority donated this bus to the Illinois Railway Museum in 1965. While the bus is complete and unrestored, sadly, it is not operational. That would probably explain why I have never seen the bus running at the museum.

Ultimately, Twin Coach did not find much lasting interest in the Super-Twin, and only a handful were ever built. There are lots of photos online of transit operations testing Super-Twin demonstrator buses in the 1940s, but the idea did not stick. The bus at the Illinois Railway Museum is one of the only known survivors.

Too Ahead Of Its Time?

There is no official explanation for why transit lines didn’t scoop up the Super-Twin, or why Chicago had only one. However, I think the bus might have been a victim of the times. The first one was built only a couple of years before Twin Coach would get involved in the World War II effort, and by the time the war was over, articulated bus technology had already moved on to the completely bendy buses that we are familiar with today.

At the same time, as the Maryland Transit Administration notes, articulated buses fell out of favor in America as fewer people took public transit and instead drove cars. The drought would last until the late 1970s, when American transit operators began importing articulated buses as a way to reduce costs by putting more people in one bus.

Whatever the reason the Twin Coach Super-Twin failed, it’s a weird blip in bus history. It was a bus that, realistically, was only half-articulated. It was supposed to beat streetcars and regular motor buses, but like the streetcars it was marketed as being better than, it went extinct.

Still, I appreciate the crazy ideas that Twin Coach put out back in those days. It seems to me that Twin Coach wasn’t so much a company that asked “why?” as it instead asked “why not?” Because of it, at least for a tiny moment in history, the largest mass-transit road vehicle in America was a half-bendy bus.

Top photo: Twin Coach

Great article. These days they’re also running double articulated busses in Utrecht, The Netherlands.

Link to Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Van_Hool_AGG300

When I saw diesel electric I immediately thought Letourneau, but Twin Coach is an equally logical choice. These are intriguing as an alternative to the GM hegemony we got

Love this, thanks Mercedes! What ever they paid the driver to maneuver this around city street corners was surely not enough. The thought of driving something like that around people and traffic is anxiety inducing for sure!

A slinky bus is a object I want to own at some point, for some reason.

I like to imagine it went like this:

Bus Engineer: I’m working on some concepts for a new bu..

Bus CEO: What?

Bus Engineer: A new bu…

Bus CEO: I’m sorry. I’m going to need you to articulate that “bus” better.

Bus Engineer: Gimme a few weeks.

As someone who is a huge transit nerd, and former bus company employee, I’ve always been fascinated by this vehicle and others by Twin Coach. Mostly it was a victim of timing, due to the rise in cars and less demands on public transit.

The most popular size of HD/Low floor bus in the U.S. and Canada is the 40ft.

60fts artics exist for a few reasons, but the largest reason is often overlooked. The sunk cost of a single driver of a 60ft artic vs two drivers in two 30ft-40ft buses (salary, benefits, etc..). Another benefit is that a 60ft artic can turn significantly tighter vs the 40fters.

The unfortunate thing is that the articulation joint in the middle of modern day New Flyers and NOVAs are all from a specilized company in Europe, adding to the cost of them. And NOVA is leaving the U.S. market to “focus on Canada”… which is really saying that NOVA is failing once again, Volvo will probably try to unload them back to the Quebec governement, or something like that.

So… soon the U.S. will be left with a single bus supplier for 60ft articulated buses, since Gillig doesn’t make one. BYD in the U.S. market doesn’t really count anymore since they pissed off everyone.

As someone who lives in a place very dependent on articulated buses (Seattle), I’d love to hear/read more about this!

Seattle has an interesting public transport system, and I’ve dealt with the leadership at KCM and I have always had a good experience with the WA state transportation folks, state-wide.

I’m not 100% certain, but I think that Seattle KCM has the most amount of 60ft artics in the country.

If you want to nerd out even harder, here is the public link to an excel file which shows all the vehicles owned by all the transit agencies in the U.S.

From 100 year old cable/street cars, to locomotives, to light rail, to buses.

https://www.transit.dot.gov/ntd/data-product/2023-annual-database-revenue-vehicle-inventory

The newest data is 2023, they are usually 2 years behind on reporting this, not sure why.

Enjoy!

As someone who teaches in schools on behalf of transit agencies, you have just made my day! Thank you!

I can absolutely believe that we have the most 60ft articulated buses – they’ve been a huge part of our transit spine, and are very helpful with some of the weird intersections that are right in the middle of high volume routes. As they expand their BRT-lite systems (Rapid Ride) and others while simultaneously electrifying, I’m curious to see if that percentage holds.

Glad to hear! You might want to dig around at other files on the NTD website. Other interesting info to pull from there too.

Apparently, Seattle is #2 behind NYC on articulated buses.

King County Metro fleet – Wikipedia

They don’t seem to do well in the snow. I’ve seen video of them sliding down Queen Anne Hill as articulated as they can get.

AFAIK, Pierce Transit, down here in Tacoma, don’t have any articulated buses.

Driving any bus, no matter its size or design, would terrify me. The biggest things I’ve wanted to drive are U-Haul Ford E350 box vans pulling a car on a dolly or the 14-passenger E350 van, picking up elderly members for Fairmount Presbyterian Church in Cleveland Heights, OH.

In my teens, my dad drove trucks pulling bottom dump trailers for construction. And he (also terrifyingly) let me drive his IH and then Kenworth tractors bob tail (without trailers) a couple of times. That was educational (also illegal) and taught me respect and courteousness for commercial truck drivers. It’s a tough job.

Good point on the snow issues. This has been an issue with artics because they have the powertrain/drive wheels on the last axle, so it’s like “pushing a rope” in the snow.

There have been plans for (but I don’t think it’s happened yet) to have electric motors on the center axles for EV/hybrid applications.

European articulated buses (or at least some) have the engine lying flatt in the first section or against the side, so the drive wheels are the middle one.

I have always preferred driving front-wheel drive vehicles in snow and ice, but I imagine it would be difficult to package that in a bus. I liked the “pushing a rope” analogy. It’s like the old Audi ad where some engineer says, “it is better to pull the car than to push it.”

Mercedes had some FWD bus stuff in the 80s (I think), and those odd wide-body COBUS buses you get on only on airport tarmac? Those are front wheel drive too, which is why they can have a low floor all the way to the back.

Interesting. I’ve been on only one of those airport buses in all my years of travelling. Where was it? Charlotte? Maybe not. That airport is decently laid out. Somewhere back east in the states to make a connecting flight.

When the bus turned, did it pivot around the center wheels, more or less? I would think a lot of cars would get side-swiped by the rear end of the bus swinging wide as it turned.

Yeah, the pivot point was more or less in the middle, so turns must have looked pretty interesting.

It’s interesting to me that the explanations of cost savings don’t talk about an obvious factor – labor.

In my days as a bus rider I would vastly prefer crowding to be dealt with by having more buses running more frequently than to have one giant bus running less frequently. But that would have meant hiring more drivers.

I think another factor driving consolidation is brought up in Tom Vanderbilt’s great book Traffic. Car drivers hate buses because they feel they make traffic worse, even though a robust bus system means less traffic.

The concrete aggravation of waiting a minute behind an unloading bus vastly exceeds the harder to understand effect of 20 more cars on the road. But drivers tend to wildly overestimate their own intelligence and objectivity, and can’t believe their emotional response is clouding their judgment.

So the pressure on bus systems from drivers is toward consolidation. The irony is that infrequent buses which carry tons of people take a lot longer on average at every stop.

I love the articulated buses in Chicago, and I happen to live near two routes that get them often/during rush. At the same time, they do feel less like a single contraption and more like a tractor-trailer situation.

One thing I do know is that if you sit in the seats that are inside the articulating section it’s really easy to get motion sickness.

Great article! These big people movers are super interesting and creative.

I want an RV modeled after the Fageol Safety Bus.

Mercedes, look at this. It was used as an alternative articulated bus

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Trailer_bus

Trailer bus

Trailer bus

Does whatever a trailer bus does

Can it float on a lake

No it can’t, it’s a bus

I, too, love the deep dives on weird public transit vehicles. I also think that Twin Coach had a really good pitch with “hey, these are faster and cheaper to put into use than a streetcar”, and I would love to see more dedicated bus-rapid-transit lanes rather than overpriced and limited use and route streetcar systems (Looking at downtown Oklahoma City here…).

Great read, Mercedes! Can’t wait for the story on the articulated engine compartment.