Turbochargers fill the automotive landscape today, and you’ll find them in everything from basic family cars to world-beating supercars. But there was a time when the appearance of a metal snail in the engine bay of a passenger car was novel, and General Motors was a leader in the technology. In 1962, General Motors launched the world’s first and the world’s second mass-production turbo cars, the Corvair Monza Spyder and the Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire, respectively. Both of these cars were ahead of their time, but the Oldsmobile was totally bonkers, and required owners to use a bottle of so-called “Turbo Rocket Fluid” just for it to work correctly.

Before I begin, I want to clear the air here. The 1963 Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire is frequently reported by several generally authoritative automotive outlets to be the world’s first mass-production turbocharged passenger car, but that is not true. The Jetfire was introduced at the New York Auto Show in April 1962. The Corvair Monza Spyder beat it by mere weeks, as it was introduced at the Chicago Auto Show in March 1962 (and also hit the market earlier). However, I don’t think that diminishes GM’s achievement here. Its brands launched not just one, but two revolutionary turbo cars within only weeks of each other, and both cars took different paths to achieve their results. Both cars are proud examples of the engineering prowess of General Motors.

Both of these cars came from an era when automakers were thirsty for power. People living in the 1960s got to witness the rise of the muscle car and gross horsepower numbers rising into the stratosphere. But before the act of putting big V8s into smaller cars became mainstream, two General Motors brands sought greater power through forced induction.

A Boosted History

The concept of forced induction wasn’t new in America. Back in the 1930s, automakers like Auburn, Cord, Duesenberg, and Graham each experimented with supercharging. The Germans were playing with supercharging even earlier than that.

Turbochargers had been around since 1905, when Swiss engineer Alfred Büchi earned a patent for what is considered to be the first practical turbocharger design. Early on, the turbocharger was used as an aid for aviation. Naturally-aspirated piston engines have a knack for losing power in the decreased air density of higher altitudes. By slapping a turbo onto an aircraft engine, the aircraft can keep its high performance, even at high altitude.

Turbos hit their stride in World War II, permitting aircraft like the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, the Consolidated B-24 Liberator, and the Lockheed P-38 Lightning to fly high with impressive power numbers. Forced induction was found all over aviation during World War II, and it allowed aircraft engines to hit quadruple-digit horsepower.

After the war, forced induction came into its own on the road. Heavy truck and farm equipment producers found themselves in a pickle. Power demands kept rising, and the traditional method to get more power out of a diesel was to up displacement. But bigger diesels were heavier and more expensive. Turbocharging offered a novel way to increase power. Commercial diesel engines would embrace turbocharging during the 1950s. Meanwhile, automotive marques like Ford, Kaiser, and Studebaker tried their hands at supercharging.

A centrifugal supercharger was seen as an imperfect alternative to more power back then. The mechanical design of a supercharger meant that its speed was dependent on crankshaft speed. Superchargers back then didn’t make a ton of boost until the engine was revving high, leaving the low RPM and middle RPM regimes without much grunt. Superchargers were also known for being noisy, unreliable, and expensive. Putting a big blower on a car was good for competition, but it hadn’t quite worked that well in a regular street car.

In the late 1950s, engineers at General Motors decided to embark on an adventure of their own. Out of the other end, they would create the Corvair Monza Spyder and the Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire. Today, I want to highlight just how bonkers the Oldsmobile was.

It’s ‘Free’ Horsepower

As Motor Trend wrote in May 1962, engineers were enamored by the promises of turbocharging. Power demands for cars were increasing, and engineers turned to the waste product of combustion, engine exhaust. The thought was that by having exhaust gases drive a turbocharger, you could achieve a “free” energy boost.

In theory, this “free energy” concept made turbos better than superchargers. A supercharged engine will use a portion of its output to drive the supercharger to get back more power. But a turbo is not concerned with driving screws or belts, and just needs flowing exhaust gases. Of course, the reality is that, despite claims in the motoring press back then, turbos aren’t completely “free” energy, as there’s still backpressure. But the idea was sound.

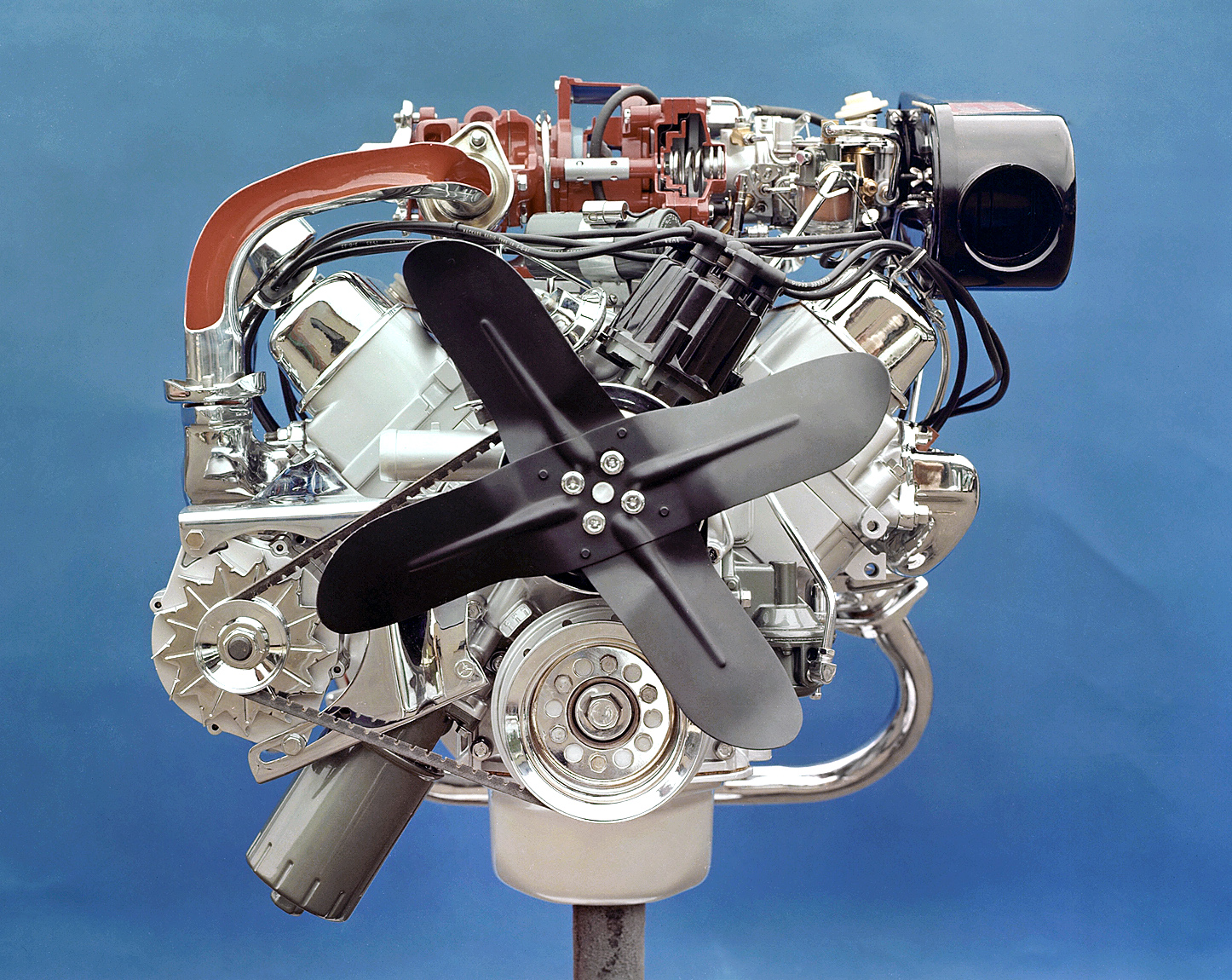

General Motors didn’t go into its solution blindly. As Ate Up With Motor writes, from 1954 to 1959, General Motors Research Laboratories embarked on an early turbocharging experiment. This explored the possibility of getting supercharger-like boost through wasted exhaust gases. Reportedly, GM Research Labs started with simulations before installing a turbo onto a simple single-cylinder engine. Eventually, GM’s testing resulted in at least one Oldsmobile Rocket V8 getting outfitted with a Schwitzer turbo.

In 1956, Research Laboratories activities manager Alfred L. Boegehold published a presentation that suggested that aluminum engines were possibly the future, and that slapping a turbo onto an aluminum engine could result in a favorable power-to-weight ratio at only slightly higher fuel consumption than a cast-iron engine. GM’s research into turbocharging initially went nowhere, but now, it was going to be put to use.

The Motor Cities National Heritage Area writes that Ford was working on offering the intermediate Fairlane’s 164 HP 260 cubic inch V8 in its compact Ford Falcon. This would eventually happen in early 1963, but GM would initially take a very different path to getting more horses in a smaller body. The Oldsmobile team, which was led by engineer Gib Butler, partnered up with Garrett AiResearch, which had extensive experience providing turbos for commercial diesel applications. The Corvair team, which was led by engineers James Brafford and Bob Thoreson, went with a turbo from TRW.

The teams at Chevrolet and Oldsmobile were more or less in a race. Oldsmobile announced its turbo in the summer of 1961, and was supposed to be the absolute first to the market with a mass-market turbo car. However, technical snags delayed the introduction of Oldsmobile’s car, allowing the team at Chevrolet to catch up. When Motor Trend wrote its May 1962 issue, Oldsmobile and Chevrolet were so neck and neck that the press didn’t know who would be first.

Oldsmobile Engineers Stretch 1960s Technology

What would make Oldsmobile’s effort different was in the way that it handled the turbocharger pressure curve. Back then, turbochargers were known for comically huge lag. Basically, early turbos made basically no boost at low RPMs and still not enough boost at medium speeds. In practice, this meant that some turbo vehicles felt gutless until near the end of their rev range, when the turbo finally wakes up with a kick of boost.

Oldsmobile engineers came up with what they believed was the best of both worlds. Their Garrett turbo would make its full 6 PSI of boost at a range of between 2,000 RPM and 2,500 RPM. Oldsmobile engineers then decided that they wanted their engine to make 6 PSI across its entire rev range. This was a departure from the Corvair’s turbocharger, which was allowed to increase its boost significantly as the engine accelerated.

Oldsmobile kept its boost consistent through a boost bypass system. Specifically, Oldsmobile fitted the F-85’s turbocharger with a wastegate at the turbo’s inlet. This wastegate is controlled by a diaphragm and any pressure that exceeds 6 PSI is diverted from the turbo. This wastegate is also a safety device and prevents the turbo from over-speeding when the engine is at redline.

(What’s pretty neat is that, per Motor Trend, the Corvair’s turbo technically had over-speed protections, but without Oldsmobile’s expensive and complex wastegate. Instead, Chevrolet’s engineers decided to bake in enough exhaust back pressure that the Corvair’s turbo wouldn’t run away. Of course, in practice, there were situations where a Corvair’s turbine could overspeed).

Embedded below is a Jetfire advertisement. Click here if you cannot see it.

Things got really crazy when it came to how Oldsmobile engineers tried to retain something resembling good fuel economy in the Jetfire’s 215 cubic inch “Turbo-Rocket” V8. One of the quirks of turbocharging is detonation. Boosted air is hotter (compressing air adds energy to it, speeding up its molecules, which bounce against one another and against cylinder walls, yielding higher temperatures; also, there is some heat transfer from the turbo itself to the incoming air). This already hot air is then heated even more during the compression stroke, and runs the risk of causing the air and fuel mixture to detonate at an inopportune time, potentially causing destructive engine damage.

The simple method to get around this, as was employed by the Corvair team, is to lower the engine’s compression ratio. This has the side effect of making the engine thirstier and also slowing an engine’s low-end response. The Olds team wanted their engine to be both thrifty enough and powerful, so the turbocharged version of the aluminum Rockette V8 had the same 10.25-to-1 compression.

Alright, so how did Oldsmobile prevent detonation? It turned to aviation technology. Oldsmobile fitted the F-85 Jetfires with bottles of what it called “Turbo Rocket Fluid,” which contained 50 percent methanol, 50 percent distilled water, and small amounts of lubricants. Oldsmobile sprayed this water and alcohol mix into the throttle body when the engine was under boost, cooling down the charge and preventing detonation.

Additional safety protections in this system involved a metering valve (consisting of a double-float and valve assembly) and a secondary butterfly in the throttle body. If the boost was too high, or if fluid didn’t reach the valve, the secondary butterfly would close, limiting the air and fuel mixture from the carburetor to the engine. This system, which was all mechanical using pressure or vacuum from the intake manifold, was effectively like an early version of limp mode when it reverted to a failure mode.

If my explanation wasn’t clear, here’s how Autocar described it back then:

“The nozzle is located in a part of the passage that forms a long venturi to obtain the desired pressure drop; the ratio of fuel to fluid remains close to 10:1 throughout the engine’s rpm range.”

Of course, in a naturally aspirated engine, this drop is created when a cylinder falls during the intake stroke, whereas turbo tech allows air to be sent into the engine at a pressure above atmospheric (‘boost’ pressure).

“Under cruising or coasting conditions, with the throttle partly open, there is a high vacuum in the intake manifold, so there is a check valve in the metering system to prevent fluid from being sucked into the engine at low or nil boost pressure. When the boost pressure in the manifold reaches 1psi, a diaphragm in the fluid metering valve opens a ball check valve, and the pressure in the fluid container tank forces the fluid through a jet to the injection nozzle.”

Oldsmobile’s Jet Age Turbo Car

All of this engineering was brilliant on paper. The 215 cubic inch Rockette V8, now called the Turbo-Rocket V8, saw performance raise from 185 HP and 230 lb-ft of torque to 215 HP and 300 lb-ft of torque. It breathed from a Rochester one-barrel side-draft carburetor, featured stronger mean bearings and connecting rod bearings, as well as strengthened valve heads and seats.

Buyers had a choice between a four-speed manual or a three-speed Roto-Hydramatic, which most buyers getting the auto. Wet, the car was 2,850 pounds, and you got a 3.36 rear axle. The F-85 Jetfire’s price was $3,045, or $350 more than the Oldsmobile F-85 Cutlass in which it was based on.

The Jetfire wasn’t just a first-generation GM Y-body with a turbocharger. The Jetfire was given a sort of unique look that was created by grafting the hardtop from a Buick Skylark onto an F-85 convertible. Inside, the occupants got bucket seats, a center console, a floor-mounted shifter, and a neat gauge that indicated either fuel economy or power.

Despite the engineering triumph of Oldsmobile, the F-85 Jetfire was fraught with issues right from launch. In September 1962, Motor Trend published its road test, and the publication didn’t hold back any punches.

Motor Trend‘s first complaint was that it couldn’t get its hands on a manual, so it had to conduct its testing with the automatic. The first sign of trouble happened during 60 mph testing, when the Jetfire hit 60 mph in 10.2 seconds. The publication said it conducted its acceleration tests six time and that was the best the car could do.

This was a problem because, as Motor Trend noted, when it tested a sedan with the 155 HP, naturally aspirated version of the same engine and an automatic transmission, that car hit 60 mph in 12.7 seconds. The publication didn’t see enough improvement for the added complexity. The review didn’t stop there, and pointed to its test of the Pontiac Tempest in 1962, which hit 60 mph in 10.5 seconds despite having a weaker 166 HP engine.

Motor Trend believed that the Jetfire’s failure to launch was two-fold. The first problem was in the transmission, with the publication saying that the box took longer than a second to change gears. The other problem claimed by the review was in the bypass system. In the publication’s testing, the engine pulled strongly to 4,600 RPM, and then fell flat on its face and wouldn’t rev any higher. Then, the transmission shifted gears, the revs reduced to 3,100 RPM, and the car would cross the quarter mile at 3,800 RPM. Motor Trend described the feeling as being like driving a naturally aspirated car with too small of a carburetor.

The publication figured that what happened is that the bypass system wasn’t allowing the Jetfire to live up to its full potential, and thus the engine fell flat at sky-high RPM. What was also reportedly frustrating was that the boost gauge was pointless, as it didn’t really indicate boost and maxed itself out as soon as you got on the throttle, anyway.

Other complaints included non-power brakes that faded quickly and the requirement for premium fuel only.

But not everything was bad. Motor Trend reported that the wizardry of Oldsmobile’s engineers resulted in negligible lag at low speeds. The car also averaged 14.1 mpg despite its sporting ambitions. Reviewers also felt that the car handled reasonably well, was comfortable, and was otherwise a decent car. The publication ended its review by saying that the Oldsmobile’s turbocharging experiment wasn’t too satisfying, but it hoped that GM would continue to refine turbos, because the promise was huge. Autocar was more impressed:

Our report said: “Maximum efficiency is designed to come in between 2000 and 2200rpm, but boost remains high up to 5000rpm. Maximum power is developed at 4600rpm, as against 4800rpm for unblown versions of the V8.

“In normal driving, the turbine will cruise at 40,000rpm. For maximum acceleration, the throttle is opened wide, and the turbocharger has a remarkably quick response, accelerating to about 80,000rpm in less than a second.”

The most amazing part of all this, Autocar’s man considered, was that “the turbocharger is absolutely silent and free of vibration, not only at normal speeds but also when accelerating, reaching maximum and when idling.”

Too Ambitious, Too Soon?

Americans were impressed, too, and started buying up Jetfires to live out their Jet Age dreams. Unfortunately, as Hagerty notes, these owners would have to deal with some major headaches. Embedded above is a dealership promotional film, and it’s deeply weird. Click here if you can’t see it.

Remember the bit earlier about the Turbo Rocket Fluid? In theory, each five-quart bottle was supposed to last 500 miles to 2,000 miles. However, depending on how hard you drove the car, you could empty it out in only 250 miles. Many owners then forgot to replace the fluid, leading to their cars entering into that aforementioned “limp mode.” The mechanical parts that made up the system were also prone to leaking and failing. As you can guess, yep, that put the car into a low power state, too. If the leak was bad enough, the fluid could flow through the intake manifold and into the cylinders when the engine was off. When you next tried to start the engine, it could hydrolock.

That wasn’t all, either, as the engine’s oil pump was insufficient to lubricate and cool the turbo. Another issue was that if you parked the car immediately after driving it hard, the Turbo Rocket Fluid bottle might be left pressurized. As Hagerty noted, there wasn’t even a service manual at first, and Oldsmobile dealer techs didn’t even know how to fix them, either.

It took General Motors a while to address these issues. The Jetfire sold for only two model years, 1962 and 1963, over which 9,607 copies were built. In 1964, GM implemented a fix for the car remaining pressurized when parked with a relief valve. But this wasn’t enough. By 1965, the Jetfire had proven to be unreliable enough that many owners just didn’t want to deal with the turbo anymore. At the request of owners, dealers began removing the turbo systems and replacing them with four-barrel carburetors and new exhaust manifolds. Allegedly, by 1970, GM had converted 80 percent of the Jetfires to natural aspiration.

Ultimately, General Motors went back to building iron block V8s. The muscle car era rolled around, and cars were equipped with ever larger V8s that made more power than the Turbo-Rocket without forced induction. Turbocharging would gain traction again a decade later in the 1970s.

In the decades since then, one man, Jim Noel, has been singlehandedly bringing the old turbo dream back to life. Noel restores the Jetfires that come his way and upgrades them with higher flow oil pumps, pressure relief valves, and other fixes that make these cars more reliable today than when they were new.

Unfortunately, the Jetfire was a rare car when it was new, and it’s believed that these cars have a low survival rate. Thus, don’t be surprised to pay something like $50,000 or so when you find a good one for sale.

Despite all of these issues, the Oldsmobile F-85 Jetfire marked an important milestone in automotive history. Oldsmobile’s engineers were ambitious and tried to make a boosted V8 with lots of power, decent fuel economy, and little lag. This car was decades ahead of its time, even if it pushed the limits of early 1960s technology.

Today, turbos are all over the place, and they’ve been refined into something you can ignore for most of the life of your vehicle. Turbos are in everything from economy cars to supercars. But they all had to start from somewhere, and back in 1962, General Motors didn’t just make history once, but twice!

I’ve always wanted to build a restomod out of one these! I’d be happy to use a F-85 or Cutlass as a base though rather than a rare real Jetfire. I think it’d be super cool with a modern fuel injection system and turbo tech and a 5-speed. And better brakes/suspension while you’re at it….

History repeats. Today the goal is build a car with a small 3 or 4 cylinder engine with performance. The problem is that the block, rotating assembly and head gasket have to be up to the task, if not headaches follow. I’m looking at you Ford

Grandpa drove from San Jose to San Francisco every night to work the graveyard shift for the Union Pacific Railroad. He was an Oldsmobile man. His first car that I recall was a 1949 Futuramic 2-door Club Sedan. He would refer to that car as “The Motor,” which may have been a reference to its Rocket V8.

In 1963, he bought a new Oldsmobile F-85 4-door sedan. The same brown pictured above, dog dish hubcaps, three speed auto. But, with the 215 and its power to weight ratio, it was a great sleeper. I’m sure he didn’t choose the Jetfire, like a lot of potential buyers, since it was new technology and needed Ethyl.

He handed it off when he bought a new Chevy Impala in 1972. My sister and I shared the F-85 as we each started driving in high school. Unfortunately, she rear ended a Buick one day and totaled it. Fifty plus years later, I still find it hard to forgive her.

The car I took my DL test in was a ’65 Oldsmobile Dynamic 88. From what I can find online, it had a 394 CI V-8. I personally it tested several times on the way to Sunday School, after I got my DL and it did 0-60 in 10 seconds. I tried different launch strategies. Plant your foot (like in the videos) and it would just roast the right rear tire. No Posi-Traction on a big Olds sedan. So, 10 seconds to 60 became my benchmark for a fast car. And it got 15 mpg, if driven very conservatively.

My ’86 Accord, matched the time with a little front wheel drive drama. And got 33 mpg, on a long trip, so that was amusing.

My ’17 Accord V6, can get to 60 in under six seconds, spinning both all-season (not sticky modern tires) from a standstill, spinning them again shifting to second and chirp them again shifting to third. And gets close to 40 mpg on a long, conservatively driven trip.

All on regular fuel and no turbo rocket fluid.

Turbo Rocket Fluid. Great name. It’s basically like Sparks and Four Loko pre-2010 before the FDA removed the caffeine, guarana, ginseng, and taurine from the delicious sugary malt beverage.

“…featured stronger mean bearings and connecting…”

There’s the problem. They would have been better off using “nice” bearings.

Copy-editing is a weak point on this site. But I usually can figure out what the writer meant.

Easy to figure out, but amusing nonetheless.

To paraphrase the adequate Bill McNeal from “Newsradio”:

Gazziza dillznoofuses! Bill McNeal here saying get with the crizappy taste of Turbo Rocket Fluid! Turbo Rocket Fluid’s got the upstate prison flavor that keeps you ugly all night long! You wanna get sick remember, nothing makes your feet stank like Turbo Rocket Fluid! DAAMN it’s CRIZAPPIN’!

I read all of this in Phil Hartman’s voice. He was probably fresh off a sandwich from the vending machine, made just like his mother used to…. In large batches and left out for a month.

Great article, Mercedes.

Thanks