The diesel engines that power most of the world’s heavy-hauling semi-tractors are large, heavy, and complex units. They have countless parts that can go wrong and are often packed into spaces that make them hard to work on. These engines also often return only single-digit fuel economy. Back in the 1950s, Boeing thought it had a solution. It developed the Boeing Gas Turbine Engine, a turbine that was less than 13 percent of the size of a truck diesel, and with far fewer parts. Boeing hoped the engine would revolutionize trucking and maybe even farming. Instead, the idea flopped so hard that few people remember it, and a big part of it was that the truck got a whopping 1 mile per gallon.

The gas turbine has often been seen as a sort of transportation holy grail. In theory, a turbine has a lot going for it. Turbine engines have high power-to-weight ratios and tend to be significantly smaller than a reciprocating engine designed to have the same power output. In theory, this means that the turbine engine will also weigh significantly less than an equivalent reciprocating engine. The potential benefits go even further than that, as turbines have fewer moving parts than reciprocating engines and, when tuned right for the correct application, can return impressive efficiency. In several decades past, it was also believed that turbines were much cleaner for the environment than reciprocating engines.

A modern turbine works by drawing air in through an inlet, where it goes into a compressor, which pressurizes the air using airfoil-shaped spinning blades. That pressurized air is then joined by fuel and is ignited in the combustion chamber and burner. The ignited high-pressure and fast-flowing mixture enters the turbine, which has more airfoil-shaped rotating blades. The mechanical work of the rotating turbine can be used to spin a propeller shaft, driveshaft or generator. The turbine is also connected to the shaft that drives the compressor. A turbofan engine is a type of turbine, and the long shaft containing the turbine and the compressor is capped off with a gigantic fan featuring titanium blades.

That is a simplified version of how turbines work, but I think I got the point across. Turbines are the durable and powerful workhorses of commercial aviation and military aviation, but there have been countless times throughout history when engineers wanted to use the same technology here on the ground. The most famous example of this is the Chrysler Turbine Car. Toyota and Rover also experimented with turbines at different eras of automotive history. General Motors would spend three decades trying to put turbines into everything from transit buses to all kinds of concept cars.

But there was a time when just about everyone had turbine fever. Perhaps the most infamous turbine project was the Union Pacific Gas Turbine-Electric Locomotive. The GTELs were the result of the Union Pacific’s unquenchable thirst for a single locomotive to rule them all. The GTEL was America’s most powerful locomotive, but it was thunderously loud, had exhaust so hot that it cooked birds mid-flight, it melted concrete, and it stopped making sense the second bunker fuel stopped being dirt-cheap.

Turbines also snaked their way into the trucking industry. These engines were touted as putting out tons of performance with fewer moving parts, a lighter weight, great long-term reliability, and maybe even better fuel efficiency. This was catnip for some engineers. A lighter and smaller engine could result in a smaller and lighter truck that carried more weight, which was a huge deal when, in the past, trucks were severely limited in length and weight.The most famous turbine truck projects include the Ford “Big Red,” the GM Bison, and the International TurboStar. Predating all of these trucks is the time when Boeing and Kenworth joined forces in an attempt to create the ultimate truck.

You might wonder why Boeing was trying to make the ultimate truck when its primary focus was aviation. As Popular Mechanics wrote in August 1953, getting into trucking wasn’t Boeing’s original intent. The plane builder began turbine research in 1944 with the initial goal of just exploring the new technology. At that time, Boeing had a jet propulsion laboratory that was only a year old. The U.S. Army was interested in jet power, and Boeing thought that a large jet transport could be successful. However, gas turbines were still an emerging technology, and Boeing wanted to look into that, too.

It wasn’t long into Boeing’s research when its engineers discovered that gas turbines had tons of untapped potential. Gas turbines, Boeing thought, could be used for far more than aviation. A gas turbine could power a small plane or a Navy boat, work as a jet engine starter, or propel a bomb or a missile. The possibilities seemed endless.

Boeing’s first gas turbine was the Model 500, which came to life for the first time in 1947. The Model 500 was a turbojet that weighed 85 pounds and made 150 pounds of thrust. Boeing marketed this engine, but found no takers. So, its engineers would improve the Model 500 to make more power while also evolving the concept into a turboprop.

The Model 502 first came online in 1947 before going into production in 1949. Instead of using jet blast for thrust, this engine would spin a propeller. The first versions of these engines weighed 140 pounds and made 120 shaft horsepower.

Later in 1949, Boeing hoped to get a contract from the Navy, and sent six of its turbines to live in personnel boats. In late 1951, a Model 502 powered a Kaman K-225, which was the first flight of a gas turbine-powered helicopter. A year later, a Model 502-powered Cessna XL-19B Bird Dog became the first turboprop plane.

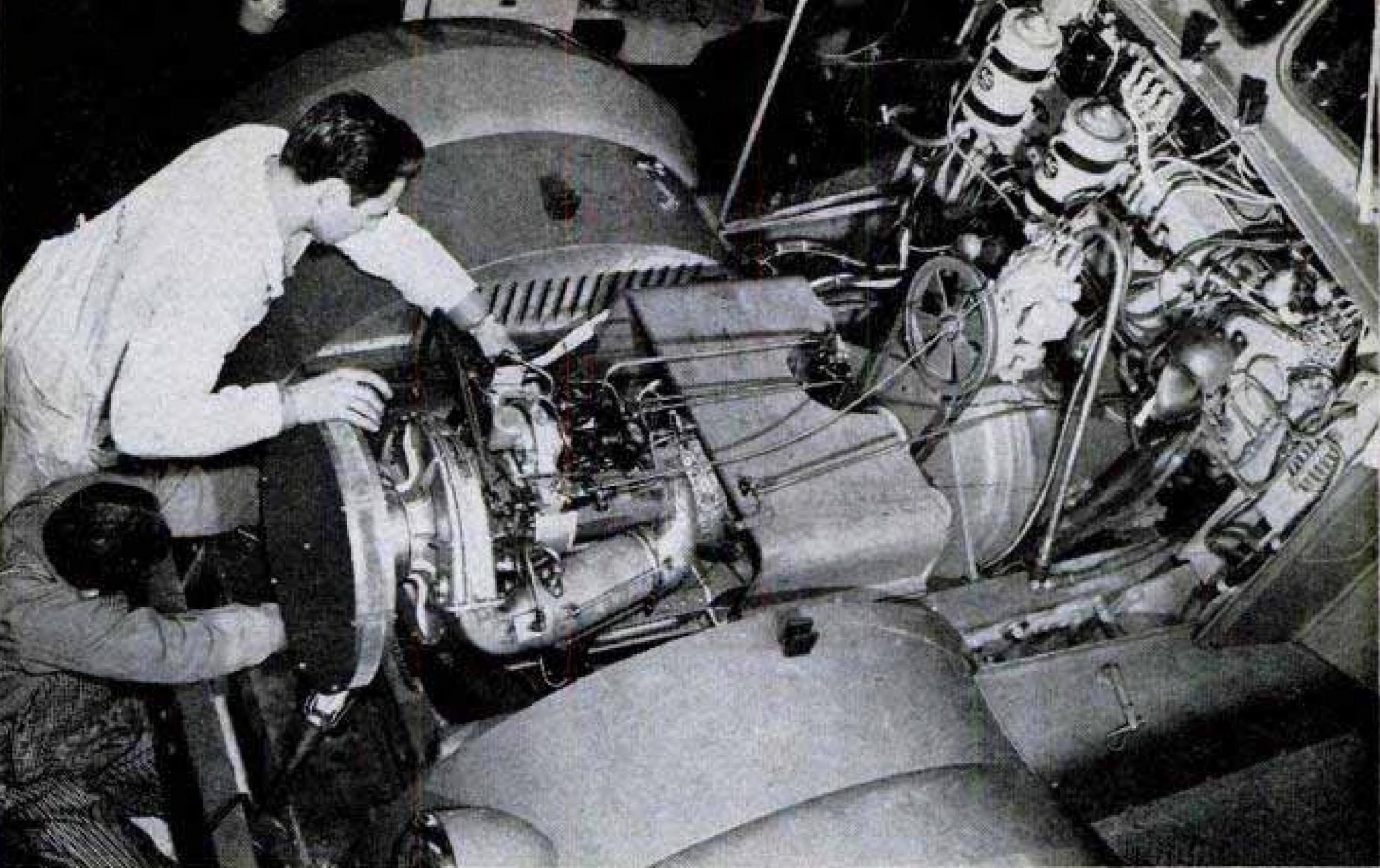

But Boeing also recognized that its gas turbines had far more applications than just the ocean and sky. In 1950, Popular Science reported Boeing reached out to Kenworth and suggested that its revolutionary new turbine could lead to innovation in trucking. Kenworth bit, and in that year, Kenworth fitted a 200-pound, 175 HP Boeing Model 502 gas turbine into the engine bay of a Kenworth conventional.

The Turbine Kenworth

The Boeing and Kenworth partnership seemed like a natural fit. Both companies were in Seattle, and Kenworth even had some aircraft experience after having built B-17s and B-29s during World War II. Kenworth saw the potential advantages of aviation power in trucking.

This truck would grab headlines all over America. Apparently, many of those publications called the Model 502-powered Kenworth a jet-powered truck, but that’s not true. The engine that powered the truck turned a rotating shaft.

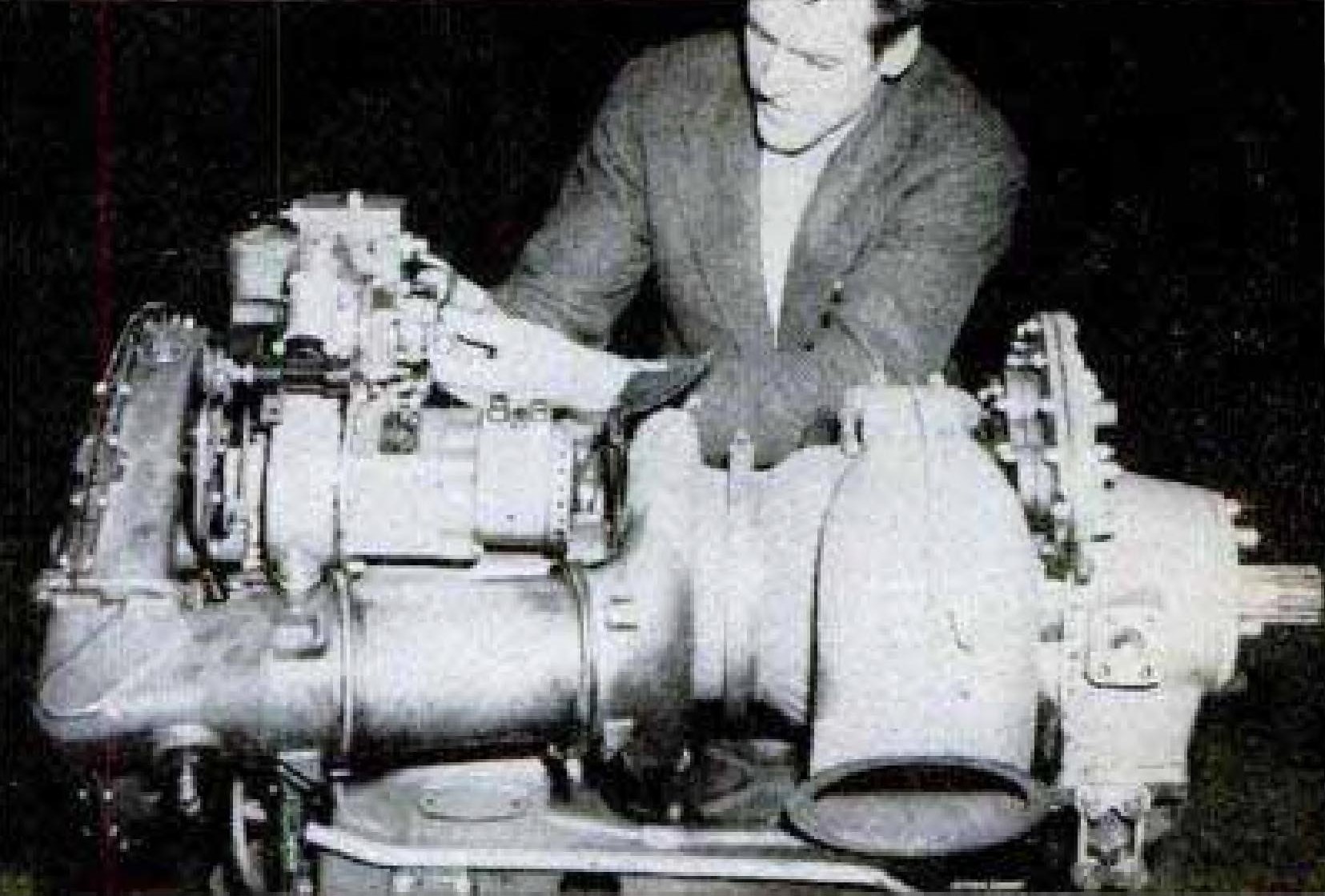

Here’s how Popular Mechanics described the engine in August 1953:

With 175 horsepower in “pony harness” the Boeing gas turbine engine is only 40 inches long, 23 inches wide, and 22 inches high, occupying less than 13 percent of the space required by a diesel truck engine. Weighing 200 pounds (plus about 60 pounds of accessories), it is 2500 to 3000 pounds lighter than present diesels of equal output. While the average diesel engine has 1400 parts and the average automobile engine 890, the gas-turbine engine has 400. Although normally operated with diesel oil, it will burn high or low-octane gasoline. kerosene, stove oil or jet fuel.

Lloyd E. Hull, one of the engineers involved in the project, described the engine’s application in a semi-tractor:

“You have to think of this engine in two stages,” said Hull. “In the first stage, a centrifugal compressor rotates at a maximum speed of 36,000 revolutions per minute. Sucks air like a vacuum cleaner, then compresses it to three times normal atmospheric pressure and delivers it to the burners. As fuel is fed into the burners, the temperature is raised to a maximum of 1500 degrees Fahrenheit. The hot gas then passes through the first-stage turbine wheel. This wheel extracts sufficient power from the gas stream to drive the compressor which is on the same shaft.

In the second stage, the gas stream passes through another turbine, which is not on the same shaft as the first-stage turbine wheel. The second-stage or power turbine wheel operates at 25,000 revolutions per minute. This is reduced in an 11:1 reduction gear to drive the truck. The system is really simple.”

On paper, this engine was almost the holy grail. It made nearly one horsepower per pound and took up less than 13 percent of the space of a diesel.

Unlike Any Other Truck At The Time

Boeing and Kenworth chose West Coast Fast Freight, Inc. as their testing partner, and trucker John Kelly had the privilege of driving the first and only gas turbine semi-tractor in service. Reportedly, wherever he stopped, the truck gathered crowds, and other truckers just had to know if that turbine was living up to its promise. Kelly was the perfect man for the job, as he had enjoyed both a long 16-year career in trucking and was also a World War II pilot who expertly avoided Japanese fighter aircraft in dozens of missions.

When interviewed by Popular Mechanics, Kelly put on quite the show when just starting the truck. From Popular Mechanics:

With 68,000 pounds of gross weight to be moved, Kelly pushed the starter button. As the fuel-pump pressure climbed quickly to 100 pounds per square inch, he opened the engine-control valve linked to the fuel Valve. The engine fired.

A warm-up period is not necessary with the turbine, but Kelly, from long habit, let the motor idle a moment. From the two huge exhaust stacks on opposite sides of the cab came a low, even roar, like wind rushing through a cave. Mingled with this sound was a high-pitched whistle from the reduction gears. Like a singing teakettle; not loud, but steady.

“Should have heard the whistle before a silencer was put on,” grinned Kelly. “You could hear it four miles away. Eventually, the researchers will probably eliminate the whistle entirely. But it doesn’t bother me. I really don’t hear it — most of the time.”

Kelly went on to say that the engine was so smooth that you didn’t feel it. This was great for reducing fatigue, as both noise and vibration can wear out a trucker on a long day. Kelly was also impressed with the acceleration, commenting that while a diesel truck might need 15 gears, the turbine truck had only six, and you really only used four of them.

When Popular Mechanics rode in his Kelly’s cab, he even pulled off a stunt where he stopped the truck dead on a hill, put it in second gear, and then pulled away. Kelly bragged that he wouldn’t have been able to do that in a fully-loaded diesel truck without starting in first and then shifting multiple times. If you were reading science magazines back then, you had to think turbines were the future. Everything said thus far sounds awesome!

The Turbine Was Hot And Thirsty

It was in that same article that some cracks in the turbine started to show. One of them was that 175 HP wasn’t even near the most powerful for a truck back then. The article described that more than one truck passed the turbine rig while on a mountain climb. Kelly shrugged it off, saying that Boeing was working on a more powerful version of the turbine.

The other problem was that the Boeing turbine ran really hot all the time. The turbine was at 900 degrees to 1,200 degrees Fahrenheit during normal cruising speeds, and sometimes climbed as high as 1,500 degrees during acceleration and hill climbs.

Boeing recognized that heat was a huge issue, and one that its engineers had spent years trying to fix. The aircraft manufacturer said that the turbine blades were made out of cobalt, nickel, tungsten, and chromium. This was important because, per Boeing, these materials could withstand only so much heat. The engine was already blazing hot as it is, and more power was not really possible without melting the engine down.

In fact, one of the issues caused by the insane heat was that the truck’s turbines cooked themselves to death, which meant that they had to be replaced more often than comparable diesels. Boeing’s response to that was saying that it would take four men 18 hours to replace a diesel engine, but a Boeing turbine could be replaced in four hours by only two men. I’m not entirely sure that’s still a positive since it wasn’t like a trucking company would have gotten replacement engines for free.

The biggest problem with the Boeing-Kenworth turbine truck wasn’t its lower power or the fact that the engine was a brick of heat, but the fact that it was hilariously terrible on fuel economy. The average big rig of the 1950s got 5 mpg. The turbine truck? It got one mpg. That’s not a typo; it burned a gallon every single mile.

To its credit, Boeing recognized that the abysmal fuel economy was a big problem. This is especially the case in trucking, where a truck that might get only 2 mpg more than average might be heralded as a genius idea. In Boeing’s case, it somehow made a truck that was more expensive in every possible metric, which is impressive. Boeing said that its scientists were actively looking for other metals it could use to make more powerful engines that offered better fuel economy.

The hits kept on coming for West Coast Fast Freight and the turbine Kenworth. As Hemmings writes, the trucking company’s Seattle to Los Angeles trip would end up taking four or five hours longer than usual because the truck was so slow. On top of that, the piping-hot exhaust blasted from the turbine at incredible speed, and the turbine had a knack for killing clutches when it wasn’t tearing itself apart. Kenworth and West Coast Fast Freight gave the project a few years and canned it. Sure, the Boeing turbine was buttery smooth and weighed only 200 pounds compared to the 2,700 pounds of a diesel, but the advantages were few. Kenworth says it canned the project on its end based on the abhorrent fuel economy alone.

Maybe Farming Or Firefighting?

But Boeing didn’t give up, and figured that maybe if a turbine couldn’t work in trucking, maybe it could revolutionize farming or fire engines. In 1958, Boeing sent a Model 502-10C turbine to live inside an Allis-Chalmers P-91 crawler tractor. By now, Boeing’s turbine was making 240 shaft horsepower, but it had also gained weight to 320 pounds. The engine also failed to catch on in farming for similar reasons why it didn’t work out with Kenworth.

In 1961, Popular Science reported, Boeing gave it yet another try, sending two Model 502s to American La France, who fitted them to a pair of fire engines and put them into service in San Francisco. By now, Boeing’s engineers thought they had finally created the holy grail. The Model 502, at least as it was applied to the two fire trucks, made 330 HP and weighed 325 pounds. Finally, the engineers achieved a true one horsepower per pound of weight. The engine was still small at only 41.5 inches long, too.

The Turbo Chief, as it was called, out-pumped all of San Francisco’s diesel pumpers and demonstrated no issues climbing the 20.2-percent grades of San Francisco’s streets. Finally, Boeing fixed the power issues.

However, even San Francisco had to admit that the Turbo Chiefs weren’t perfect. As Hemmings wrote in a different article, the engines were $10,000 more (or about a third more) to purchase than an equivalent gasoline engine, and the turbines got approximately half of the fuel economy. Mind you, I’m talking about half of the fuel economy of a gas engine here, so we’re talking about really awful fuel economy. Consider that a fire engine might get up to 5 mpg, and at times will get 1 mpg. Slicing that in half is shocking.

However, San Francisco figured the money would even out in the end because diesel and kerosene were cheaper than gasoline and because Boeing promised that the turbines would be more reliable than reciprocating engines. As it turned out, Boeing’s promise didn’t work out. Whenever something broke, Boeing had to fly an engineer out to San Francisco to fix it, and parts were expensive. When the fuel control governor failed in one of the turbines in either 1966 or 1967, which would have cost $3,000 to replace, San Francisco went right back to reciprocating engines.

Terrible, But Awesome

Ultimately, Boeing’s bid to revolutionize trucking, farming, and firefighting had failed spectacularly. Racer Jack Zink even tried to repurpose a Model 502 from a Kenworth truck to turn it into a rear-engine Indy 500 car, but the car failed as proper gearing could not be found.

This is not to say that the Model 502 was a total failure. The Model 502 was the propulsion of the world’s first gas turbine-powered helicopter and the world’s first turboprop light airplane. It seemed that the Model 502 worked as an aviation engine, just not as a truck engine.

Still, I get why it was done. The promises of the turbine were too hard to ignore. How could Boeing and Kenworth not give it a try? It’s also easy to see GM, Ford, International, and others gave it a try, too. While turbines might have sucked as truck engines, it’s awesome that they existed in the first place. At least for a few years, there were trucks darting up and down the West Coast with 1,500-degree tiny engines that got only 1 mpg.

Top Graphics images: Boeing-Kenworth/NASM)

There is a Turbine Mack Cabover at the Mack Museum in Allentown PA

If they could solve the noise problem it might make a good genset. Put magnets in the main turboshaft (at high speed) with static coils around it. One moving part (the shaft and associated blades). Still, a jet really isn’t efficient of fuel unless it runs impossibly hot.

“That’s not a typo; it burned a gallon every single mile.”

Bugatti Veyron gets 1 litre per 1 km (2.35 mpg) at 400 km/h (248 mph). The entire 100-litre tank would be emptied out in twelve minutes at that speed…

Makes those Nascar guys at Talladega look like they’re winning the Mobilgas economy run!

Lotus also had a gas turbine car, the 56

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lotus_56

Three of them raced at the 1968 Indianapolis 500, one of the cars was leading with just 8 laps remaining when it retired.

A Mercedes Streeter Deep-Dive on this – the car, the reactions to it, the race, if it could have realistically won – would be a great read.

I wonder what was the Thermal Efficiency Delta between ICEs and Turbines during that era versus today. If Diesels were twice as efficient at producing work, then of course turbines would lose. However, today’s efficiencies put them on a much different footing. Obviously the internals of turbines make them far more expensive to produce and maintain than diesels, but from a pure efficiency perspective, the idea of turbine powered trucks is far less crazy now than then.

I’d argue it’s even more crazy now vs then, purely because of aftertreatment. Piston engines can deal with a bit of backpressure from catalysts better than turbines can, plus turbines tend to run lean for efficiency and to avoid overheating the already super hot turbine blades. However this is awful for NOx production (hot plus excess o2 with atmospheric nitrogen gives you NO and NO2), which is more difficult to catalyze on it’s own when not running stoichiometrically. The excess flow rate from running lean and the fact that the turbine isn’t a positive displacement pump all adds up to bigger losses from any aftertreatment. Plus, turbines don’t like to change speeds and loads, so in normal operation on a truck dealing with shifting, traffic, grades etc, the turbine will be less efficient

While I didn’t mention emissions, I do fully agree that they are almost certainly an insurmountable factor. I was in no way suggesting anyone even consider turbine trucks, just saying that if efficiency is/was the ostensible sole goal, then the attempt makes more sense now then in the fifties.

I like Scania’s newest approach to aftertreatment. They left after treatment out of the initial design process, and made an engine that runs hot and efficient, burning basically all of the particulate matter. This also negates the use of EGR cause they’re not trying to cool combustion.

“But more heat makes NOx!” Yes, but now they don’t have to worry about particulate. So they deleted the DOC and just use two stage DEF injections to deal with the higher NOx.

There’s a lot more to it, but I like that they turned conventional emissions development on it’s head, and ended up simplifying the aftertreatment process.

I don’t know the difference in thermal efficiency, but that metric is far too overrated when talking about traveling land vehicles. Most of the time, a land vehicle isn’t running full load for max power and converting as much power to work as quickly as they can, they’re running lower loads at steadier speeds to move the greatest distance possible using the least amount of fuel, which means being able to stretch out the time scale that the fuel used is converted to work. The 4-cycle engine reigns because it is able to stretch the time the fuel’s burn can contribute to the work with only 1 combustion event every other revolution per cylinder and torque that allows potentially generous gearing to extend the work farther in terms of distance travelled per unit fuel. A turbine is burning fuel constantly and there is no real way to consistently convert enough of the power produced into useful work in a road vehicle. It makes a ton of power (and uses a ton of fuel), but it can’t properly be used because it’s a mismatch in application.

See my above reply.

Turbine EV range extenders? (Mostly kidding)

Porsche might have us all driving six strokers someday…

Thanks for reading and replying to my thought experiment post. 🙂

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Brake-specific_fuel_consumption

Look at the chart under “examples for shaft engines”

Diesel is better even in EREV comparison.

Jaguar’s C-X75 was originally supposed to be powered by a pair of micro turbines producing electricity for electric motors.Very cool, but not even remotely practical.

Even today diesel beats the best “portable” turbines in BSFC. Unless you can figure out how to make a combined cycle gas turbine portable turbines will never be better for trucks.

We can take out all the other variables and run an EREV setup. Run both engine types at peak bsfc to charge batteries. Unless you design a scaled down portable combined cycle gas turbine, the diesel wins.

I’m honestly baffled here. Less crazy is still crazy. I don’t think I suggested anyone try this. But I still maintain that based upon efficiency only, it makes more sense today than seventy-five years ago.

However, a combined cycle truck would be absolute peak steampunk awesome. Never going to happen, but I’d love to see it. That would be cool.

I heard that turbines were used in at least one MBT at some point in a series hybrid configuration, so at least for military uses there is some viable advantage they have (size/packaging? weight? fuel flexibility? noise? complexity?) over diesel, likely in spite of its poorer thermal efficiency and also an application where emissions aren’t considered.

Absolutely, I spoke only to efficiency.

Turbine power density is king.

Marine turbines are used all over the world in various configurations, mostly by navies.

Sounds like the big problem was a brayton cycle turbine running at a 3:1 pressure ratio with only a single stage compressor, which is fundamentally going to be very inefficient. Even in the 50’s, it should have only taken a quick, basic thermo calculation to show that the efficiency would always be absolutely terrible with that little compression. To get good efficiency out of a turbine or piston engine, you need high pressure ratios, such as the 40-60:1 pressure ratios from multistage compression out of the modern airframe turbines, or 16-20:1 CR (+ turbocharging) of modern diesel engines.

I’d guess they could have made a turbine with higher pressure ratios from multistage compression back then, but it would have added cost and complexity as you point out. Even today, you’d still need the complex, high pressure ratio turbines to compete with modern diesel engines in efficiency, there’s just no way around the fundamentals.

I have spent some time around the Chrysler turbine car, and the idea that executives thought that was a reasonable solution to personal or commercial ground transportation seems outright ludicrous. The sound is so objectionable, and the heat and exhaust that the Chrysler emits is wildly inappropriate for something you would expect to drive around town. Those guys must have had A LOT of confidence that engineering would eventually solve the heat and noise issues.

Turbines seem like they are almost the future for a lot of ICE applications, but they always fall short.

While the lack of efficiency and cost were highlighted as major reasons in this trucking example, I really think heat, as well as their typically crazy high spinning speeds would ultimately make most turnbines fail for non-aerospace applications. The turbine engines in these trucks were still very much new designs. I have no doubt that they could have been made more reliable, easier to maintain and to some degree cheaper (except that the materials used will always keep costs fairly high). But the heat is not something you can really manage all that well in these smaller ground vehicles applications. It’s just an insanely hot engine that will cause wear and other problems for a lot of other components in something as small as a truck or in a car like Chrysler’s test turbine car.

You know what they say:

Boeing, Boeing, Bong!

Trucking took another go at this in the 70’s. Freightliner made a series of “Turboliners” in the 70’s with turbines from Detroit Diesel and Ford. By then they improved the fuel economy to 2 mpg. Still to low

Obligatory mention of the MTT Y2K motorcycle, still in production, also gets around 5mpg.

“The Model 502 was the propulsion of the world’s first gas turbine-powered helicopter and the world’s first turboprop light airplane. It seemed that the Model 502 worked as an aviation engine, just not as a truck engine.”

Why would it work as an aviation engine if it was 1/5th as fuel efficient as a piston diesel engine and more expensive to boot? I get it’s lighter but its not like fuel isn’t without its own weight penalty.

Lower weight, higher RPMs, better reliability . . .

Weight is.offset at least in part by the extra fuel needed Higher RPMs need reduction gears if it’s.a.turboprop or turboshaft. Those also add weight. That leaves reliability which ain’t nothing but its not everything, especially in multi engine setups.

The speed range possible of the exhaust and bypassed air when used as a turbo fan (can be matched well with air speed), the inherent compensation for lower air density at altitude, plus the good efficiency at steady state in a specific region of the operating map make it a good match as long as aftertreatment isn’t required for air travel (and air travel produces tons of NOx in addition to a mediocre to poor carbon footprint)

I think the relatively constant load of aviation is a big part of it. Turbines don’t like to change RPM, but I think the inefficiency issues are mitigated somewhat at high, constant, load. Plus the disadvantages of noise and heat are easier to deal with on an airplane.

I think that in combination with the light weight and high reliability was enough to push them to become the default for aviation, but it is still rather surprising!

I’m training as an aircraft mechanic right now, and the prices on everything turbine-related do just seem so absurd. I have no intention of ever owning a plane, but I sure wouldn’t want to deal with the costs of a turbine if I did!

I’m pretty sure EVERYTHING aviation related is priced absurdly. Even small piston engines that have been in production since the 1950s. Part of that is likely due to scale, Lycoming “has built more than 325,000 piston aircraft engines and powers more than half the world’s general aviation fleet, both rotary and fixed wing.” By contrast GM alone produced 100M small block V8 engines from the 1950s to 1997 with the introduction of the LS series.

As I recall there were people putting those much cheaper automotive, even some motorcycle power plants like Corvair flat sixes and LS V8s into light aircraft. I imagine a Corvar engine with modern gaskets, electronic ignition, EFI and a better cooling fan setup could be quite reliable in an aircraft and perform well with a turbo.

Oh yeah, everything aviation is absurd; it’s just that turbine stuff adds an extra multiplier on top of normal absurd!

Scale probably has a lot to do with the cost, as well as low competition. I believe another big part is simply the liability involved in selling certified aviation parts. Either you have to make incredibly good parts, or have enough profit to cover lawsuits, or (more realistically) split the difference.

Yeah, automotive engines for aircraft is an interesting option! I think the difficulty is finding anything that has the full aviation certification, though that wouldn’t matter for homebuilt-type stuff. One difficulty is having redundant electrical systems, like the dual spark plugs aircraft engines usually have.

My college had a prototype Corvette V8 converted for aviation use on display, which was pretty cool!

I also remember hearing about a company that was converting Mercedes-Benz diesel engines to aviation use, which seemed like a neat idea! Diesels theoretically could work well in aviation, and can run on more readily available jet fuel, rather than the mostly US-centered leaded avgas.

“One difficulty is having redundant electrical systems, like the dual spark plugs aircraft engines usually have.”

Hemi engines have a dual plug head design but honestly I dunno how important that redundancy is anymore. It made sense when electrics were unreliable, engines were dirtier, plugs fouled constantly and needed to be replaced after a few thousand miles but now when plugs in a modern engine are fine after 100k and can probably last even longer? Coil packs also add their own kind of redundancy.

Never underestimate how conservative the FAA is about certifying anything related to aircraft engines, just look at how leaded fuel is still used in avgas for arguably stupid reasons

Oh I’m sure there are all kinds of *REASONS!*.

Awesome article! The pictures are amazing, it’s crazy how small the engine looks in the nose of the KW. Once I get my time machine working, this is gonna be the second thing I see. The first will be an old timey steamboat race.

I still think there’s a place for turbines, probably mated to a hybrid electric drive as a range extender for heavy, long-range vehicles. Think a double-decker intercity bus. Even then, that’s a niche market.

Unlikely. Turbine efficiency scales quadratically with size so smaller turbines lose efficiency rapidly. An airliner’s main engines are typically 50% thermally efficient but it’s much smaller APU is about 15% efficient.

Meanwhile piston engines scale much more favorably. A massive Wärtsilä-Sulzer RTA96-C is also about 50% thermally efficient while the most advanced light vehicle diesels are also about 50% thermally efficient.

Interesting! Thanks for sharing.

I work with aeroderivative gas turbines (operationally, not in development(, and hadn’t realized how thoroughly turbofans were kicking our butts on efficiency. Aeroderivative gas turbines peak at 44% efficiency, but as you note, that is achieved with scale-44% is on a 70MW machine; small machines in the power range of a truck are way worse. The pressure ratio they were operating at made me laugh; how on earth did they expect a 3:1 PR gas turbine to compete with any diesel, which were likely well north of 10:1 at the time?! Let alone the part load efficiency on gas turbines being even worse.

I think SOFC are the ones to keep an eye on. Bloom Energy claims up to 65% chemical to electricity efficiency on natural gas or hydrogen (if that’s your thing) and a cogen heat and power total efficiency of 90%. No noise, no vibrations, very few moving parts, fairly compact, scalable, there’s much to like.

“The pressure ratio they were operating at made me laugh; how on earth did they expect a 3:1 PR gas turbine to compete with any diesel, which were likely well north of 10:1 at the time?! Let alone the part load efficiency on gas turbines being even worse.”

I wondered that too.

Most dual spark automobile engines have an extra spark plug so they can run at higher RPMs and higher compression and still control the ignition. Also sometimes in a two valve head with big valves and ports, there isn’t anywhere to put a centrally located plug.

Of course aircraft and fire equipment have redundancy requirements.

Does that leave potential to get a truly massive turbine up to, say, 75% thermal efficiency? Is there an upper limit where making it larger won’t make it more efficient?

By that point you’re outside the realm of transportation, and probably into the world of a generator, though

AFAIK for just a simple turbine, no. A Brayton cycle engine maxes out at 60%. Jet engines are about 50% TE so there may be some efficiency left on the table but jet engines are already quite large and I expect they are already pushing the practical upper limit for size, weight, complexity, etc.

For ground based systems however one can combine cycles and eke out a bit more energy from the fuel, e.g. use the waste heat to boil water into steam and use that to run a separate turbine.

If you further use the waste heat from the turbine(s) to heat a building or hot water you can see 80+% of the energy of the fuel put to good use. That’s more of a thing for a physical plant, say for a college campus, mall, business park or tall building.

Ok, interesting!

I guess if you can use waste heat, it’s pretty easy to make things efficient, in general. If you can use all the heat, what’s left to be waste energy? Only the noise?

“If you can use all the heat, what’s left to be waste energy?”

To start with there’s the thermal difference in the waste products between ambient temperature and absolute zero. Only if so much energy is harnessed that the waste is as motionless as possible containing nothing but zero point energy have you harnessed everything it has to give. At least as far as conventional thermodynamics goes.

Now if you were to talk to a physicist they might argue there’s still plenty of nuclear energy left in the atoms of the waste and until you fuse and fiss everything until there is nothing but a lump of ultra cold iron 56 you’ve still got energy to extract.

And who knows, maybe someday in the future a much smarter physicist engineer is going to finally figure out how to use a dilithium crystal to convert half that lump of iron 56 to antimatter iron 56 and harness the annihilation energy, thus finally achieving 100% total efficiency.

At least that’s as much as the science as I know it goes. Maybe there’s even more to it.

Well hydrogen bombs are pretty efficient. They just have a problem with scaling.

Antimatter bombs are far, far more efficient. Just one ounce of antimatter reacting with an ounce of matter will release 1.22 MT of energy, equivalent to a hydrogen bomb. And of course such an antimatter reactor is practically infinity scalable from a single electron to the entire universe since it’s still a fever dream product of imaginationland.

Let’s build a gas-turbine-electric-steam hybrid!

1: Start with old steam locomotive.

2: Replace passive wheels under tender with electric motorized wheels.

3: Remove coal/oil burner and install gas-turbine electric generator in firebox. Pipe exhaust gas to boiler as before.

4: Steam powers the original drive wheels, generated electricity turns tender wheels.

It’d be several Mercedes Streeter interests blended together.

That’s be quite an orchestra of combustion.

It would be interesting , even just as a technological experiment , to see what could be done today 70 years later with this concept.

Turbines almost worked for racing too at Indy 500 in various cars and also in the Howmet Turbine endurance racer. There’s probably many more in other motorsports, but those are what stuck in my head.

wasnt there a turbine race car that used ground effect to suck the car down to the road and the technology was approved at the beginning of the season and then banned mid season when they started dominating?

I does sound plausible, and I recall various fan cars and their reading around rules, but a turbine car is drawing a blank for me.

I can see the potential problems of the turbine playing vacuum with track surface debris, but there may be workarounds for that.

Hopefully somebody knows more and can fill in the gaps.

That was The Chaparral 2J in 1970. It used a small 2-stroke snowmobile engine driving 2 fans to create the downforce. It worked – so it was banned.

I have always thought it was hilarious that the fan engines were the particular point of failure on the Chaparral. I guess it’s easy to laugh at in hindsight – I know skilled people worked on making that crazy thing happen – but it’s still a silly thing to me that the auxiliary engines were the issue.

The 2J was a back door project at GM, and as typical of GM the fan belts were underdeveloped.

Considering how quickly it was banned, the 2J worked really well.

The “moveable aerodynamic device” rule is about my least favorite. It’s so arbitrarily enforced. I mean, the entire car is an aerodynamic device and, well, it is moving.

Lots of people saw pictures of the back of the 2J and thought those fans were turbines.

Turbines became the dominant engine type in Unlimited Hydroplane powerboat racing starting in the late ’70s. They’re also pretty common in tractor pulling.

There was an STP-sponsored turbine powered Indy car in 1967, built by Andy Granatelli’s team and driven by Parnelli Jones that came within a few laps of winning the Indianapolis 500 but had to retire due a transmission failure. I was 10 at the time and my dad dragged me and my brother out to go fishing that day so I didn’t get to see it.

The Abrams tank uses a turbine engine. When I was hunting at Fort Hunter Liggett I drove by one that was running, just an absolutely crazy sound from a tank.

The American tanks are notoriously expensive and horrendous for fuel consumption next to other NATO or other non-turbines engine tanks. Argument I’ve heard is that the Americans have better logistics so can refuel more often.

Even then, piston engines were just too well-developed to beat. It happened again with the Wankel.

Is it happening again with EVs?

For a lot of trucking EV drivetrains make a ton of sense, they’re almost always better off with ICE range extenders, but the BEV drivetrain itself is hard to beat.

For long distance trucking they’re probably better off using a Honda style Series+2-3 gears hybrid transmission, which use the high transmission-efficiency mechanical gears at steady speeds. China appears to be trying to make long-distance trucking viable with high powered charging stations. As long as the trucks have enough range to last between meals, a 30-45min charge time is totally reasonable at a rest stop; if one of the 500kWh trucks BYD is making (they’re offering 4-5 size configs between 150-600kWh last I checked) can last 6-7 hours of travel, they’d need 1000kW average charging speeds to recharge in 30 mins. That probably entails using a 1500kW peak output charger, which BYD and Huawei are in the process of rolling out.

I don’t really see why it would. For long distance purposes sure, BEVs still have many drawbacks. When it comes to local commuting though, we can fairly easily produce cheaper batteries now and the electric motor is famously reliable.

I’d much rather daily a Leaf that needs zero maintenance beyond tires and occasional bearing lubrication instead of slowly killing an internal combustion engine by only driving it fifteen to twenty miles a day in stop-start traffic. If you’re charging at home and not driving very far regularly that use case is by far worse for an ICE which won’t come up to operating temp leading to oiling problems and the like.

EVs are super efficient but the cost of electricity is rising quickly and gasoline prices have remained flat or maybe even decreased depending on where you live.

Electricity is easy to make at home though. Not so with gasoline.

Tell that to my length of hose and rudimentary knowledge of fluid dynamics!

And just significantly more scalable with demand. The electricity demand may increase faster than the supply can, but the supply should be able to increase in the long term, while that’s more challenging for gasoline.

Methane is super easy to make at home.

On a serious note, ethanol is pretty easy to make at home too.

I know, I’ve made both. One is much more pleasant the other.

The challenge is to make them cheaply and abundantly to be used as fuel. I think you’re much better off begging for waste oil from your local eateries for transportation, save the methane for home heating and the ethanol for cocktails.

I see that my comment was already made.

Moving on…

The cost of electricity and cleanliness of the grid are very solvable problems now that solar has become so cheap, the biggest barriers are each country’s political situations with the coal/oil/natgas lobby and avoidance of buying Chinese products.

Australia now has so much successful solar that they’re having to subsidize their coal/natgas plants from shutting down as they’re too unprofitable during the sunlight hours. They’re currently waiting for their huge (Chinese supplied) BESS projects to complete in the next few years which will cover nighttime loads, which will allow them to shut down the legacy coal/natgas plants if they want to.

Most African countries are happily embracing solar this year now that the price has dropped even lower, it saves them from having to depend as much on oil imports.

Meanwhile, the US has outright canceled solar and wind projects that were strictly cheaper to install and operate than the new coal & oil plant plans made to satisfy lobbyists.

And the reason that the Chinese dominate solar is because they made the long term investments to make it happen. In a sense, the Chinese do capitalism far better than the west.

things are not priced based on how much they cost anymore they are priced on how much they can get away with charging people. also if fossil fuels are 60 percent of the us energy generation then fossil fuels will set the rates. Also factor in increased demand. AI is going to increase power demands by 20 percent. if we don’t put huge surcharges on AI/Data center electricity usage the AI companies will just out bid the residential customers and increase their rates. we need to force the AI company to generate their own energy to force them off the residential grid.

That’s mostly political depending on where you live.

Electricity is getting cheaper to produce, but distribution is the bottleneck and demand is skyrocketing.

EVs will win in the end.

Not with EV’s. After daily driving one for over a year, there’s no way I’d go back to ICE for a daily. The quiet is wonderful. So is the instant torque. Home charging is far more convenient than any gas station. The time I’ve gotten back from not doing oil changes or other maintenance has been appreciated. Not spending the money on that is a bonus.

Once public charging is better, EV’s are the better mousetrap. We have the technology today. What we’re lacking is the will to make it happen. Other countries do and are leaping ahead.

The real issue is that: other countries are leapfrogging ahead. Murica, soon to be a has been backwater where huge amounts of the population drive ICe pickups, don’t have health insurance and can’t afford food. Making Americans Grovel Again. Well done 1%, well done

I’m right there with ya, brother/sister. We went all EV about 3 years ago and we’ll never (willingly) go back, for all the reasons you mentioned. I’ve nearly forgotten what gasoline smells like, and when I occasionally catch a whiff, it’s disgusting.