Driving a vehicle on a beach isn’t something that people normally do unless they’re 1) maintaining said beach or 2) driving their overpriced Range Rover, Land Cruiser, or G-Wagen on the coast of Nantucket for a glimpse at the stunning orange sunrise with their designer dog in the passenger seat.

If you’re a high-ranking military official, though, beaches have another purpose: access. If you happen to be invading a country with a coastline, it might be tough to use a proper port for getting troops, supplies, and vehicles on the ground since the country being invaded probably wouldn’t like that.

Without a port and all of the infrastructure that comes with it, unloading stuff like trucks, 4x4s, motorcycles, and other vehicles onto raw beachfront isn’t easy, since these vehicles can’t easily drive through sand without stuff like special tires or running gear—stuff that might not be very useful the second said vehicles are off the beach and on solid ground.

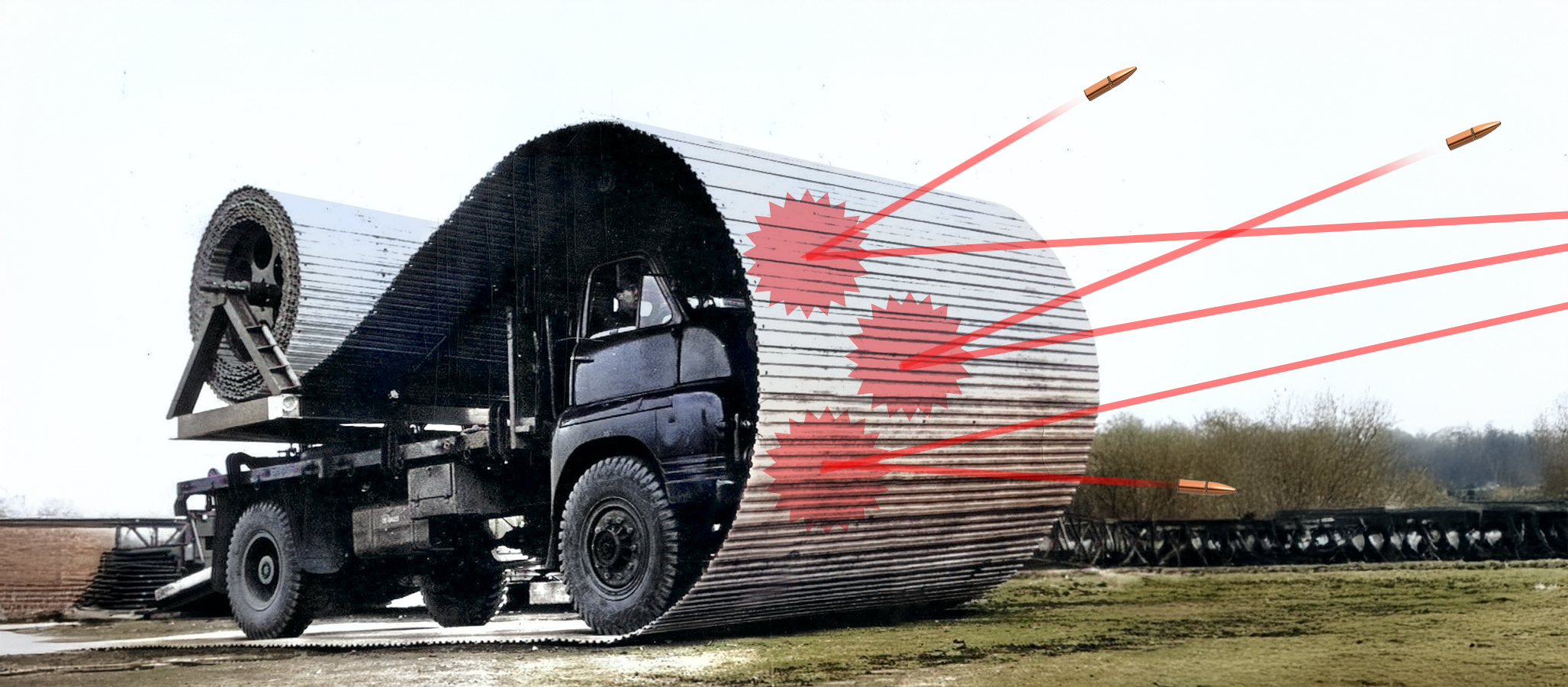

In the mid-1960s, the solution to this problem, according to the British Army, was a truck that could deploy a temporary roadway from a spool on its back as it drove forward, at the cost of frontal visibility. Its name? The Bedford RL “Bobbin.”

Where This Truck Is Going, It Doesn’t Need Roads (Because It Makes Its Own)

This funky contraption is one of those designs that probably sounded pretty strange when the inventor pitched it in a boardroom, but in action, it feels just right. It works by laying down a temporary, flexible road mat from a water-based landing craft. As the vehicle, a Bedford RL medium-duty truck, drives forward, the mat unspools from a big drum in the cargo area. The road mat is routed in front of the truck by a set of guides mounted in front of the cab.

According to the person who originally published it on the photo-sharing site Flickr, the pic above is an original press photo from 1963, when the Bedford RL was unveiled to the public. Here’s the accompanying text:

This is a press photo dated 23rd May 1963. The text on the rear states:

‘If you havn’t got a road you can always roll your own says the British Army. This truck lays a flexible track in front of it as it moves along. The truck was demonstrated recently at the Royal Military School of Engineering at Gillingham, England. It can lay 55 yards in 11 seconds.’

While 55 yards doesn’t sound like a very long road, you have to remember that all this temporary path needed to do was connect the landing craft to solid ground. So it doesn’t need to be very long. A longer version of the video published above, shared to Instagram, shows early military-spec Land Rovers exiting the landing craft pulling trailers at normal roadway speeds:

The biggest problem with the Bobbin is, obviously, visibility. Presumably, the plan here is that foot soldiers would’ve arrived ahead of time and had the landing craft beach itself so that the Bobbin would have an unobstructed path from the beach to solid ground. Then, all they’d have to do is tell the driver to go straight until they ran out of spool.

It’s also possible that, depending on how thick that temporary road mat was, the British Army would send out the Bobbin first to make a hole on the beach. What better shield for the driver than a thick piece of temporary roadway between you and the enemy’s bullets?

That being said, such a move sounds more like a stunt from an action movie, since the driver would be totally exposed once the spool ran dry. They’d also be exposed from the sides, whether the spool was in front of them or not. And the enemy might have more than just bullets at their disposal (cannons, mortars, etc.), which, if I had to guess, the temporary strip of roadway wouldn’t be able to stop. But it would sure look cool if they tried.

Even without the spool looping around the body, the Bedford RL was a pretty interesting truck. Bedford was General Motors’ commercial vehicles division, and it built a bunch of vehicles from the ’30s all the way into the ’80s. The RL was based on Bedford’s civilian-facing S-Type commercial truck, and basically looked the same from the front, save for some olive green paint.

According to Hagerty, who wrote about an RL for sale through Bonhams back in 2020, the military version got all-wheel drive and bigger wheels to increase ground clearance. That article claims the RL was powered by a 4.9-liter straight-six making 110 horsepower, mated to a four-speed manual. Bedford also made a whole lot of them, according to Truck-Encyclopedia.com:

It was rated at 3 tons originally, as all RL GS (general service) trucks in the British Military. Later, they were re-rated at 4 tons, but without mechanical modifications, the figure indicating now rated cross country payload weight. The last RL left Bedford’s production line in 1973, for a grand a total of 74,000 vehicle. This was even far more than the wartime QL series (52,247), and for this reason it became the standard British military truck for most of the cold war.

In addition to laying down temporary roads, RLs were used for a whole host of different jobs, from troop transport, mobile radio stations, supply transport, command centers, and maintenance trucks.

The Bobbin Is One Of Many Vehicles That Make Their Own Roads

This highly specialized Bedford is one of numerous vehicles that can make roads of their own, both for military and industrial purposes, such as traversing deep sand, snow, muddy, or otherwise uneven terrain. The design used by Bobbin all those years ago is still used by several pieces of machinery in the modern era. Faun Trackway, a British company, sells spool attachments that are reminiscent of the design above:

This one is the Medium Ground Mobility Solution, according to Faun’s website. All it needs is a vehicle with a payload of up to 11,000 pounds to operate, where it can roll out and under said vehicle as the machine rolls forward. It can deploy 104 feet of 10.8-foot-wide aluminum roadway in five minutes, according to Faun. The company claims it needs minimal manpower to control and operates in any climate.

In the case of Faun’s demonstration photos above, visibility is a bit better because the front loader cab isn’t totally obstructed by the spool assembly, which sits fully in front of the vehicle. You can also mount the kit in the rear of a flatbed. Watch:

In this case, the road is laid down behind the vehicle as it reverses, rather than in front of the cab, as in the Bobbin. Honestly, I think I prefer it this way, because at least I can use my mirrors to see where I’m going while I’m backing up (though I would still request a spotter if one were available).

Of course, this is one of many methods vehicles can make their own roads. The Dutch Army has a version that uses hexagon-shaped plates that are connected in gigantic square shapes:

In this case, instead of a spool, the squares are stacked on top of one another and unfolded as the truck reverses, put into place by a guide structure hanging off the back of the truck and a rope that goes from a pulley system to the center of the road pieces.

Going one step further are armoured vehicle-launched bridges, or AVLBs. Instead of laying down roads, these vehicles go one step further and deploy temporary bridges so personnel can cross terrain that would otherwise take lots of time and effort to overcome, such as ravines or rivers.

While the concept of deployable bridges dates back to the first tanks of World War I, modern iterations of these devices appeared more widely in World War II. It was here where things like the Small Box Girder (SBG) bridge were first developed, allowing tanks (in this case, the Churchill AVRE), to deploy a temporary crossing without subjecting troops to enemy fire.

The U.S. Army version, introduced in the 1950s, used M48 Patton battle tank chassis that were modified to carry a scissor-type 60-foot deployable aluminum bridge. Here’s what it looks like in action:

A more modern version of this scissor-type bridge appeared in the mid-1980s, developed after the M48 ended production and was replaced by the M60. That vehicle and its successor, the M1074 Joint Assault Bridge System (JABS), both use the same basic concept, albeit with higher payload capacities. [Ed note: G.I. Joe had one, too – Pete]

It’s impressive to see just how far the concept of vehicles that are able to lay down their own roads has come in the past century or so. While the Bedford RL Bobbin has been outdated for decades now, it’s a fun reminder of how engineers can come up with quirky yet effective ways to get things done, with basic concepts that still exist to this day.

Top graphic image: Bedford/Davis Busfield via Flickr

Still see the Bedfords all over Africa. Especially the 4×4 versions, and usually terribly overloaded…

They aren’t temporary like this, but I’ve always liked the automatic brick laying road machines.

Those things are awesome, and the ergonomics for the workers are incredible!

I’d pick the Dark Knights Batmobile, and just jump those creeks.

if it picked it back up behind itself it would just be a giant tank tread that encircled the vehicle

The amount of engineering, manufacturing, and logistics that happened in that 6ish year period of WW2 in mind blowing.

That puts a new meaning to “roll your own”

This is like the Overlanding equivalent to mass tourism on Everest.

It’d be awesome if the vehicle was only rolling out a road for itself and could recover the spool on the back after it crossed its own road.

Any ’80s GI Joe kids probably remember the bridgelayer. I thought it was just a fake toy, and that’s when my dad started educating me on military hardware oddities.

a libertarians dream vehicle

I’m guessing the only direction these things can go is “straight,” so as long as you knew there was nothing blocking your path, you didn’t really need to see, unnerving as that would be.

I’d need several spotters if someone wanted me to drive this thing as intended

You should do a deep dive into “Hobart’s Funnies” – all sorts of mechanical creativity.

Yes, one of Hobart’s funnies was set up to do the exact same thing for Normandy, except it used a spool of canvas.

“Bobbin: A reel of 10-foot (3.0 m) wide canvas cloth reinforced with steel poles carried in front of the tank and unrolled onto the ground to form a “path”, so that following vehicles (and the deploying vehicle itself) would not sink into the soft ground of the beaches during the amphibious landing. From Wikipedia.