The Boeing 747 is quite possibly the most iconic airplane in aviation history. Everyone knows what the 747 is, even if they don’t care about planes. The ‘Queen of the Skies’ might have ended production in 2023, but several examples of the 747 will continue operating decades into the future. One of the rarest 747s in the world is this, the short and stubby 747SP. Once the choice for airlines wanting a smaller widebody with incredible range, just two 747SPs are in operation today, and both are owned by Pratt & Whitney Canada. Both of these aircraft are flying laboratories used to test new engines. Yep, when this plane is at work, it has five engines!

Pratt & Whitney Canada’s Boeing 747SP is known as a flying testbed. These specialized aircraft allow for real-world testing of new aircraft engine designs. The development path to bring a jet engine into service is a long one and requires comprehensive testing before the engine can earn its airworthiness certification.

Among these tests, Simply Flying notes, is a static test where all of the engine’s modules and componentry are tested without the engine running. Once the engine is ready to advance, it’ll be tested while running on a gigantic engine stand on the ground. These stands tend to be inside wind tunnels or test buildings. Engineers will run the engine at various speeds and monitor its sensors as well as noise levels. Necessary changes are made to the engine design after these tests.

Torture-Testing Jet Engines

Rolls-Royce provides some information about how it tests engines:

We subject them to freezing conditions

While your only temperature problem in the cabin might be the over-active air conditioning, outside, at 40,000 feet, the mercury can drop to as low as -60 degrees Celsius. In freezing conditions, ice can form on the front of the engine. It’s designed so that at a certain point, the ice safely breaks away before it can cause any damage that might affect the engine’s operation. We take our engines to the GLACIER facility in Manitoba, Northern Canada, and put them through a range of tests to push our designs to the limit. We also start the engine in freezing temperatures, when the oil in the engine becomes thicker than treacle. The Northern Lights are often visible at the facility, but teams can’t sit back and enjoy the view – during testing they take regular indoor breaks to regulate their body temperature.We drench them to the core

Planes take off, land and fly through rain and storms every day; it’s part and parcel of flying. Engines are well equipped for this, from April showers to monsoon season. However, in extreme conditions, such as hailstorms creating melting balls of ice, water can get into the engine’s core, which risks putting out the flame that keeps it alight. We design our engines to prevent this happening, and conduct water ingestion tests, where we drench the core of an engine to make sure it can withstand and continue to operate in the most extreme conditions it is likely to meet in service.We ask them to run, and run, and run…

We put our engines through gruelling endurance marathons, making sure they can handle powering intensive, ultra-long-range routes, day after day. The Trent XWB powers the longest flight in the world, from Newark to Singapore, typically an 18-hour flight which experiences a range of different weather conditions. As the next frontier of aviation is reached and airlines operate ultra-long-haul flights, we continue to test the limits of the Trent XWB. It recently undertook endurance tests in Thailand to monitor how its components behave. We simulated the equivalent of more than 1,000 ultra-long-range flights, back to back. Now that deserves a medal.

Rolls-Royce says it runs additional tests, including procedures to prove the engine can survive bird strikes without catastrophic failure, and subjecting the engine to gale-force crosswinds to make sure it can withstand the conditions without damage.

Flying In The Real World

The flying testbed comes into play when it’s time to put the engine through flight testing. While the ground-based test stand is critically important, it’s not exactly a real-world test. Jet engines have to work through huge temperature ranges as well as through varying density and pressure. These engines have to work well at sea level when it might be 90 degrees and at over 30,000 feet, where it can be -40 degrees or even colder.

To see how these engines work in the real world, engine manufacturers deploy the engine onto an aircraft. Flying testbeds can either be dedicated aircraft built just for testing or a modified version of an existing aircraft. In the very early days of aviation, new engines were tested simply by installing them onto an aircraft. However, since at least 1940, there have been dedicated testbed aircraft. Installing an engine onto a testbed aircraft allows engineers to pull live data from the engine as it’s running.

You’ll often find two common types of testbed aircraft today. One type will be a retired airliner with one of its engines replaced with the experimental engine. These aircraft will also see structural modifications as well as modifications to the wing to accommodate the test engine and all of its sensors. The aircraft interior will also be mostly gutted of its passenger seats and filled with racks of equipment, as well as potentially dozens of screens for engineers to monitor data with.

This type of engine testbed looks goofy, as the test engine will often be substantially larger than the plane’s existing engines, which makes for funny photos.

A Rare Beauty

Another type, and it’s what you see here with Pratt & Whitney Canada’s Boeing 747SP, involves taking a retired airliner and mounting an additional engine pylon on it. The aircraft retains all of its normal engines, but now the additional pylon allows for real-world testing of an experimental engine. If the experimental engine fails, it isn’t a big deal. Once again, these airliners are also filled up with racks of equipment, seating for engineers, and all sorts of monitors.

What’s really neat here is that many testbeds are vintage aircraft. They’re aircraft that had been used up over a couple of decades by airlines, but instead of getting scrapped, they get to live a fun second life.

Pratt & Whitney Canada descended into EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025 with Boeing 747SP C-GTFF, one of the only two operating 747SPs left in the world. This former airliner was delivered new to Korean Air Lines in 1981 with registration HL7457.

Then, it flew for the airline for 17 years before being transferred to Boeing with registration N708BA. In 2001, N708BA was sent to Wings World Wide – The Air Medical Foundation, where it flew for the organization for a few years. In 2004, N708BA was transferred again to TransAtlantic International Airlines. Finally, N708BA landed with Pratt & Whitney Engine Services in the States in 2007. The plane was transferred one more time to Pratt & Whitney Canada in 2010 and gained the registration of C-GTFF at that time.

For those of you counting, this means that C-GTFF is at least 44 years old, and it still looks gorgeous in its old age. Something that’s fascinating about C-GTFF is that, despite all of its ownership changes, you can still find plenty of signs in the aircraft that still have their original writing from Korean Air Lines.

Still The Queen

It was bittersweet seeing Pratt & Whitney’s testbed 747SP. The Boeing 747 ended production two years ago, and time is running out to set foot in one. There are over 400 Boeing 747s still flying today, and many of these aircraft will be flying more than a decade or two into the future, but the twist is that the vast majority of the operational 747s are cargo aircraft. If you want to plant your butt in the seat of a passenger 747, your only choices are rides aboard Air China, Korean Air, Lufthansa, and Rossiya. That’s it. Not even famed operators of the 747, like British Airways and Qantas operate the type anymore.

All of this is sad because the launch of the Boeing 747 was one of the most important moments in aviation history. The 747 wasn’t just a big plane, but the plane to launch the widebody era and one of the planes that helped make air travel so affordable today. From my retrospective:

Pan Am CEO Juan Trippe looked to capitalize on the explosive growth of air travel with an aircraft with double the capacity of the 707. The airline executive’s idea was that if Pan Am could fit more people on a plane, it could charge less per seat. And having one plane full of tons of people would reduce airport congestion. When Boeing itself looks back on the 747’s development, it mentioned the same ideas. We’d see this concept decades later–and arguably too late–with the super jumbo Airbus A380. But Boeing? It was primed to change the world.

As Pan Am was fishing for a big plane to lower the costs of travel, Boeing hoped to win a big contract, from my story:

There is another event that happened that helped thrust the 747 into existence. In 1961, the United States Air Force began looking into a replacement for the Douglas C-133 Cargomaster. This proposed aircraft would also complement the Lockheed C-141 Starlifter. A number of aircraft manufacturers took on the challenge. In 1963, the military finalized what it was looking for in its Request for Proposal for a large military transport aircraft. The project was dubbed the Cargo Experimental-Heavy Logistics System, or CX-HLS.

Boeing eventually lost the bid for the CX-HLS, but it wasn’t going to let the aircraft’s development go to waste. The 747 is different from Boeing’s bid for the CX-HLS project, but some attributes made it over. The easiest carryover to spot is the hump for the cockpit and the upper deck. To meet the military’s requirements, High-bypass engine technology was in development for the CX-HLS. Those engines would make it over to the 747 in the form of four 43,000-pound-thrust Pratt & Whitney JT9D-3 turbofans.

Just like with the 707, Pan American’s Juan Trippe had some say in the 747’s development. Targeting those aforementioned lower fares, Trippe asked for the new aircraft to carry twice what a 707 could. As the U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission notes, an early design for the 747 blew right past Trippe’s goal. This mammoth design called for two full-length decks with passengers seated in two aisles. Carrying more than 400 passengers, the Commission notes that the design called for a seating capacity three times that of the largest 707. However, concerns about emergency evacuation times and cargo capacity meant the design would be scaled back. Instead, Boeing widened the fuselage cross-section, allowing a single deck with twin aisles and ten abreast seating. Then, additional space would be found in the hump above that deck. The new design allowed a seating capacity of 366 in a three-class configuration but alleviated the need for two full decks.

Boeing 747 production began in 1967 with the type’s first flight taking place in 1969. The aircraft flew into the history books in January 1970 when the first examples were delivered to Pan American.

The 747, which was the world’s first widebody airliner, helped to make the world feel a little bit smaller. Now, hundreds of people could all board the same plane to be whisked off to a distant destination. True to Pan Am’s goal, the 747 also helped usher in an era of cheaper air travel based on the concept of cramming as many people into one plane as possible. The 747 rightfully earned the nickname of the Queen of the Skies. She was just that majestic, just that important, and that much of a game-changer.

All of this alone is enough to give the 747 legend status in the world of aviation, but the aircraft became a cultural icon, too. Suddenly, if a movie involved a plane of some kind, that plane had to be a 747, or at least clearly inspired by the 747. Even movies that didn’t need to have a Boeing 747, like the Airport series, the Turbulence trilogy, or even the wacky Soul Plane, still used Boeing 747s.

The Stubby 747

Pratt & Whitney Canada’s aircraft is the 747SP, and the “SP” stands for “Special Performance.” As the Pima Air & Space Museum writes, the Boeing 747SP was designed at the request of Pan Am, which wanted a 747 capable of flying nonstop from New York to the Middle East in a single shot. Meanwhile, Iran Air wanted an aircraft that could fly to New York without stopping. Reportedly, these routes also weren’t popular enough to sell out a full-size 747, but could sell out a smaller widebody.

According to Boeing, the 747-100s that these airlines were flying had a design range of 4,620 nautical miles with a full load of 366 passengers. The airlines wanted more.

It was around this time that Boeing also found out that it had put itself into a tough spot. Douglas and Lockheed both developed smaller widebody trijets, which bridged the gap between the comparatively compact Boeing 707 and the huge Boeing 747. Boeing didn’t want to leave this market untapped and began development on a smaller widebody. Ideally, Boeing would have done a clean-sheet design, but there wasn’t really time for that.

Early on, Boeing considered joining the fleet of trijet widebodies with a 747 design that would have called for the deletion of one engine and the placement of the third engine in the tail like a Lockheed L-1011. However, Boeing discovered that the 747 would require major wing modifications to facilitate the transition into a trijet. Instead, Boeing’s solution for a smaller, longer-range 747 was just to cut dozens of feet out of the 747-100’s fuselage, creating the 747SP. Boeing’s logic was interesting. Simply Flying quotes Boeing chief engineer Joe Sutter:

“Stretched versions of existing aircraft were already flying, and showed how a successful platform could be repurposed for a different commercial mission. So if a stretch could work, why not a chop?”

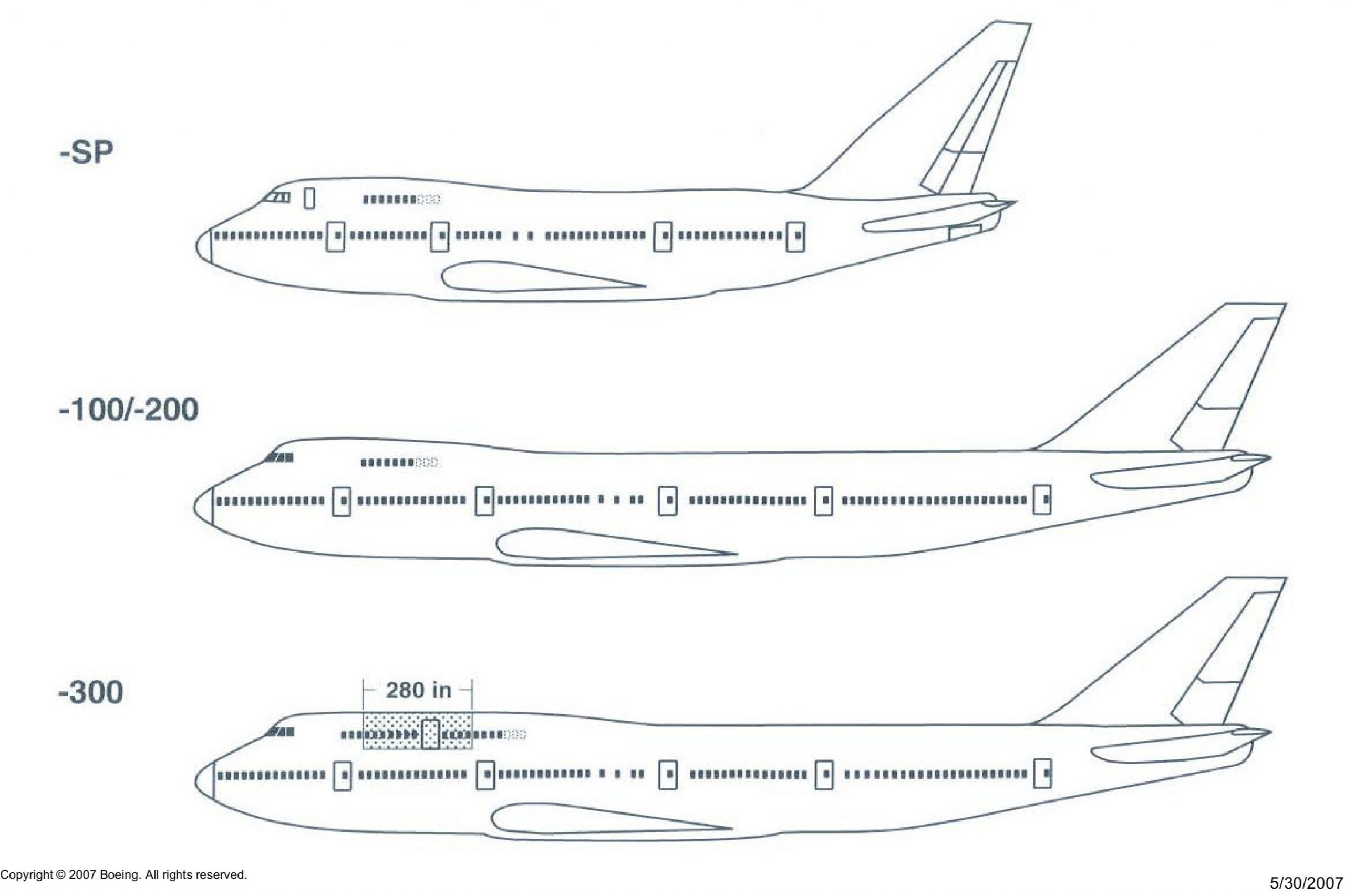

The 747SP was created by removing 48 feet and four inches of length from the 747 design, specifically from the spans of the fuselage fore and aft of the wing roots. But shortening the aircraft to a stubby 184 feet and nine inches wasn’t enough, as the 747SP had to be lighter and slimmer. As a result, Boeing cut weight out of the wings, simplified the flaps from a three-slot design to a single-slot design, added a longer horizontal stabilizer and a taller vertical stabilizer, removed four main deck doors, and added a double-hinged rudder.

Take a look at this graphic:

Add it together, and the Boeing 747SP weighed 337,100 pounds empty, or over 40,000 pounds lighter than a 747-100. But more important was its range of 5,830 nautical miles with a full load of 276 passengers, or over 7,000 nautical miles when empty. A quartet of Pratt & Whitney JT9D turbofans fire out up to 50,000 pounds of thrust. Another option for the 747SP was Rolls-Royce RB211 turbofans, which were good for up to 51,980 pounds of thrust.

The Boeing 747SP had so much range that, in 1976, when the 747SP went into service, the Pan Am Liberty Bell Express flew around the world from JFK in 46 hours and 26 minutes, with just two stopovers in New Delhi’s Palam Airport and Tokyo-Haneda Airport. Pan Am then flew another around-the-world trip a year later with another 747SP, taking 54 hours and 7 minutes with only three stopovers. The wildest Boeing 747SP flight was Friendship One, which flew around the world in 36 hours, 54 minutes, and 15 seconds for charity. That plane, which was operated by United Airlines, required only two stopovers. The flight ended up raising $500,000 for children’s charities.

A total of just 45 Boeing 747SPs were ever built, and of those, only two remain in operation. Both are with Pratt & Whitney Canada. NASA also used to run a Boeing 747SP as its Stratospheric Observatory for Infrared Astronomy (SOFIA), but that aircraft has been taken out of the sky and preserved as of 2022.

The Tour

On Monday, July 21, Pratt & Whitney offered the media a tour of one of its testbed aircraft at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2025.

During the tour, engineers informed the gaggle of journalists that a primary reason why this aircraft is still flying is due to the fact that there are some tests that cannot be performed on the ground. An engine manufacturer cannot provide definitive information about performance without having tested engines in the real world, where conditions are uncontrollable and sometimes unpredictable. This requires engineers to get these engines onto an aircraft and running just like they would be expected to on a production aircraft.

Pratt & Whitney says that it left some parts of the aircraft untouched from its days as a commercial airliner. The seats forward of the main door on the main deck come from the aircraft’s time as an airliner. As Pratt & Whitney says, the company often needs to transport company personnel in addition to testing an engine, so these seats are so that those people can fly comfortably. Pratt & Whitney also left one galley untouched, as well as the forward lavatories. The aircraft also had a lot of intact baggage compartments.

Looking at these was wild, as they looked to have been frozen in time. I spotted little artifacts around the interior from its past, like the old lavatory signs, escape ropes, and an interior comm system. All it looked old and a little tired, but it was such a wonder to see.

Pratt & Whitney informed us that the upper deck had been transformed into the base of operations for the engine pylon. Sadly, we weren’t allowed to go up there, or into the flight deck for that matter.

The rest of the aircraft had been dedicated to capturing the data from the countless sensors attached to the testing rig, as well as for the engineers who conducted the engine testing. Basically, the entire main deck from behind the main door to the rear galley was filled with server-style racks, computer screens, and controls for the test engine.

As a sort of fun fact, this Boeing 747 technically should be capable of carrying a total of six engines. The 747 is capable of ferrying a spare engine under one of its wings. Add in the special test engine rig of this aircraft and boom, you have a six-engine plane. Of course, only five of those engines would be running, but it is a funny thought.

Pratt & Whitney says it gets a lot of use out of its fleet of testbed aircraft, too. Since 2001, the company says, its testbed aircraft have participated in 1,400 ground runs and flight tests for 71 different experimental engines. The 747SP has also been used to test PW800 business jet engines and the PW1000G geared turbofan family.

Unfortunately, the 747 and what would become its main rival, the Airbus A380, were built for a system that has been minimized today. In decades past, commercial aviation worked on a “hub and spoke” model. In this scheme, passengers would fly in widebody aircraft between major hubs (think Chicago O’Hare or John F. Kennedy International), then board a smaller aircraft to their final destination, known as a spoke.

Today, airlines have adopted a point-to-point model, where smaller planes filled with fewer people will fly nonstop between two airports. These airports might be traditional hubs, or they could be two spokes. Either way, the biggest widebody airliners are bad at this task because they need to be as full as possible to operate at anything resembling a profit. It’s easier to fill an Airbus A321 or even a Boeing 777 than it is a 747 or A380.

So, these big giants of the past are slowly fading into the pages of history. If you want to get a flight on board the Queen of the Skies, I would move sooner rather than later. Otherwise, you can at least rest somewhat easier knowing that 747s will continue flying for years to come, most as freighters, but some as weird flying test rigs like this 747SP. At least for now, one of the rarest operational jets in the world is one of two 747s with an engine growing out of its fuselage.

Top graphic images: Mercedes Streeter

I was expecting to see something like a trijet with two engines on each wing instead of one. This was way more interesting!