Most of the internal combustion piston engines built for vehicles throughout history have pretty familiar core designs. The majority of fuel-burning vehicles sold today orient their pistons in inline or vee configurations. Boxers and “flat” designs are less common in cars, but remain a mainstay in aviation. There’s also the weird Wankel, which replaces pistons with a spinning Dorito of power. But what if you were to combine some genetics from piston engines and Wankels, then put them into one engine? Meet the Birotary, a crazy new and complicated engine that has three cylinders arranged like a star, a rotating block, a stationary head, and just a dab of Wankel fun.

Some of history’s most complicated engines were built to fulfill specific roles. Perhaps the craziest diesel engine of all time, the three-block, 18-cylinder, and 36-piston Napier Deltic, was designed to give the British Admiralty fast boats to best the Germans in the 1940s. Diesel engines were usually pretty weak back then, so engineers got creative to make power. Then there’s the Commer TS3, the legendary British opposed-piston diesel truck engine that fit into compact spaces and offered a unique sound, good power, and great reliability. Of course, the most common weird engine is probably the Wankel rotary, which was once seen as superior to piston engines for its fewer moving parts and high power-to-weight ratio, among other things.

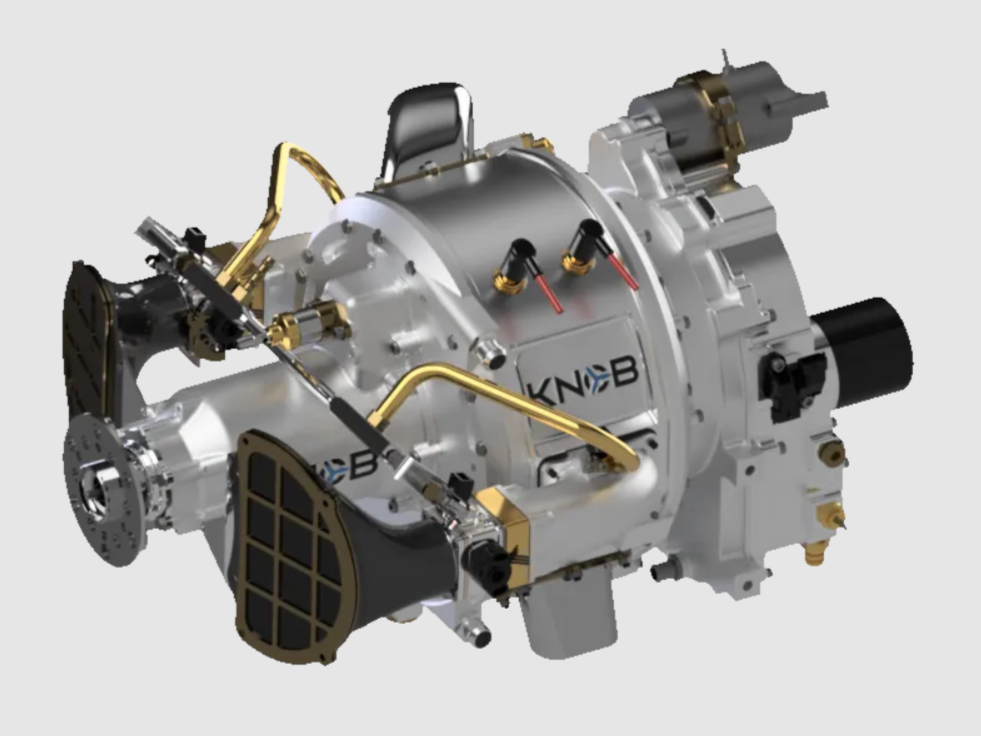

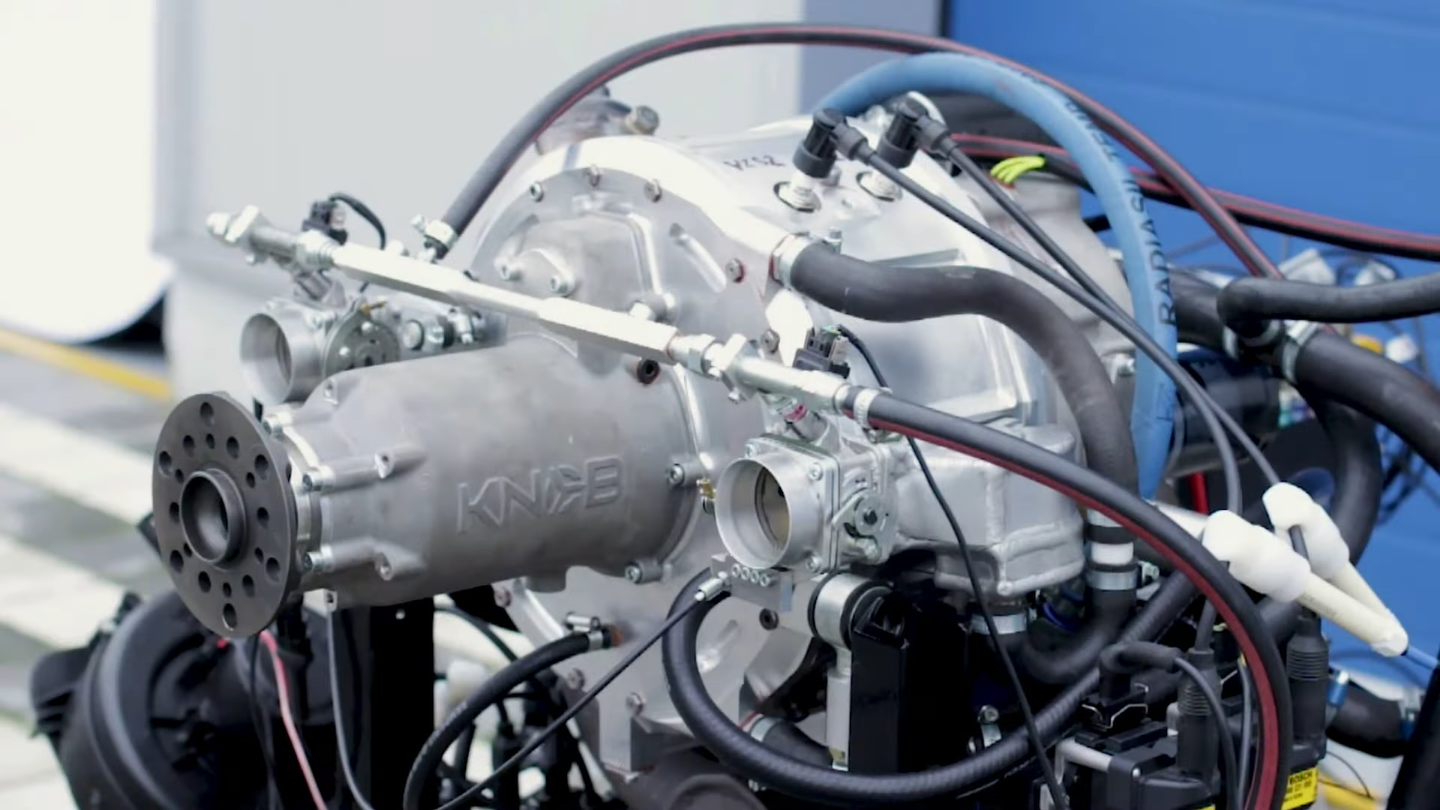

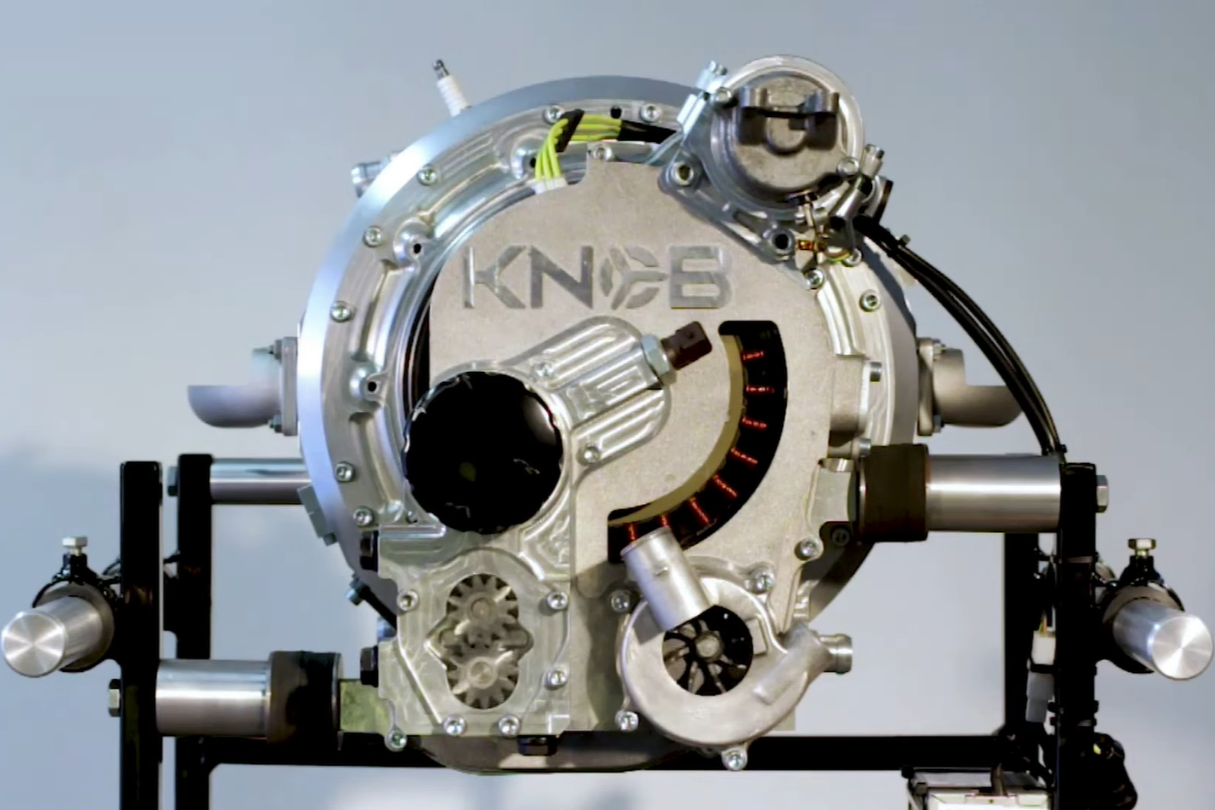

Like those engines, the Knob Engines Birotary (that’s pronounced sort of like “kuh-nob” not “knob”) hopes to make an improvement in a specific area of transportation. In this case, Knob says it designed this engine to make the ultimate light aircraft engine, one that’s light, powerful, and transmits low vibrations. The awesome thing about the engine that I’m about to show you is that it’s not a concept or something that exists in only virtual reality. A real, running prototype of this engine has been built and has already taken flight in a light aircraft. But how does this weirdo even work? Let’s take a look!

Behind The Engine

The Birotary engine is the work of Vaclav Knob and his team of engineers at Knob Engines. The company was founded in Czechia (Czech Republic) in 2010, and Knob Engines says it has been working on its Birotary from its founding. However, Vaclav says he first came up with the idea back in 1988, and he’s been tweaking it ever since. In 2014, the company says, Vaclav Knob and company managing director Jiri Drahovzal earned patents for the Birotary engine’s design and sealing characteristics in 48 countries.

Here’s the story that Vaclav tells about himself:

Was born 12th June 1964. He graduated from high industry school with a focus on aircraft technology. He also competed four years of studies at university, specializing in engines. All his professional life is focused on research and development in the automotive area. He is the author of patented technology of motor-generator presented on this site.

[…]

After leaving the Czech Technical University in Prague in 1989, where he was studying Transportation and Manipulation Technology, Vaclav has had a broad and highly successful career in engine design, research and development. Strongly influenced by his University study and his inspirational Professor Jan Macek, Vaclav has focused on combustion engine and gearbox design. Today, racing gearboxes and sequential shifting mechanisms developed by Vaclav are being used by many private racing teams.

His developments can be seen in Porsche 996, 997, GT2, GT3, Turbo, Carrera, Boxster, Cayman, also in Mitsubishi Lancer EVO, Toyota Celica, Honda Prelude, and in the vast majority of VW Group automobiles. The shifting mechanism for Porsche was developed by Vaclav in cooperation with “CARTRONIC” and the development center of “Porsche Engineering Group GmbH”. In addition, Vaclav has worked on multiple engine design and development projects for “AUDI AG” and has completed design projects on Ring-Shaped Valve engine and 2-stroke engine with swinging pistons.

Also, before we get into the engineering of this engine, you should listen to it run:

It sounds like Vaclav has quite the history with designing unique machines. Jiri Drahovzal doesn’t note any engineering in his history. Instead, he brings decades of experience in finance, import, export, and business administration to the Knob Engines team. The guys aren’t working alone, either, and have several engineers working alongside them on the Birotary project.

Vaclav also has another outfit called Knobgear, and that company is working in projects beyond the Birotary, including a range extender for electric aircraft and racing transmissions for Volkswagen Group and Honda cars.

Alright, so you know the father of the Birotary. Let’s get into how this thing works.

It’s Not What You Expect

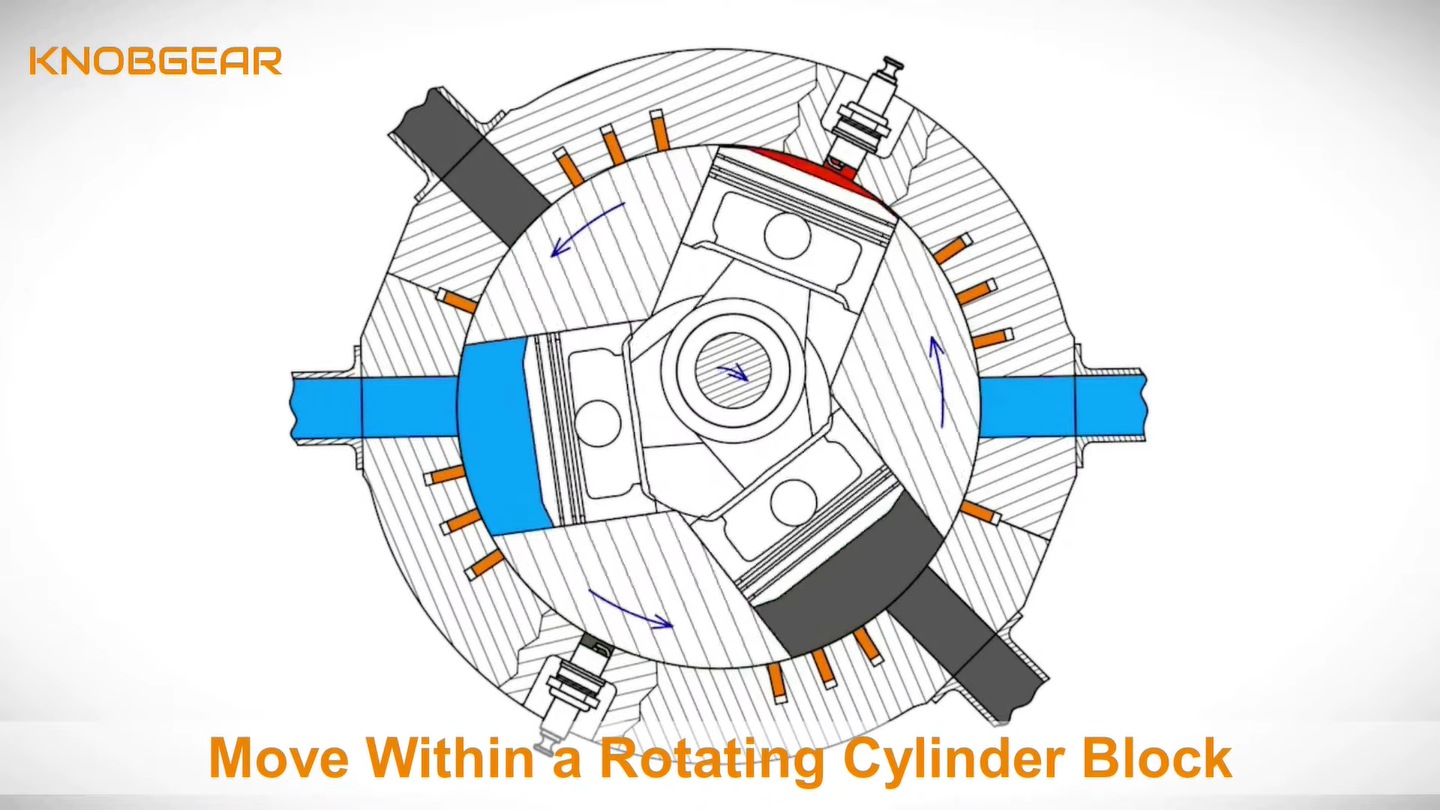

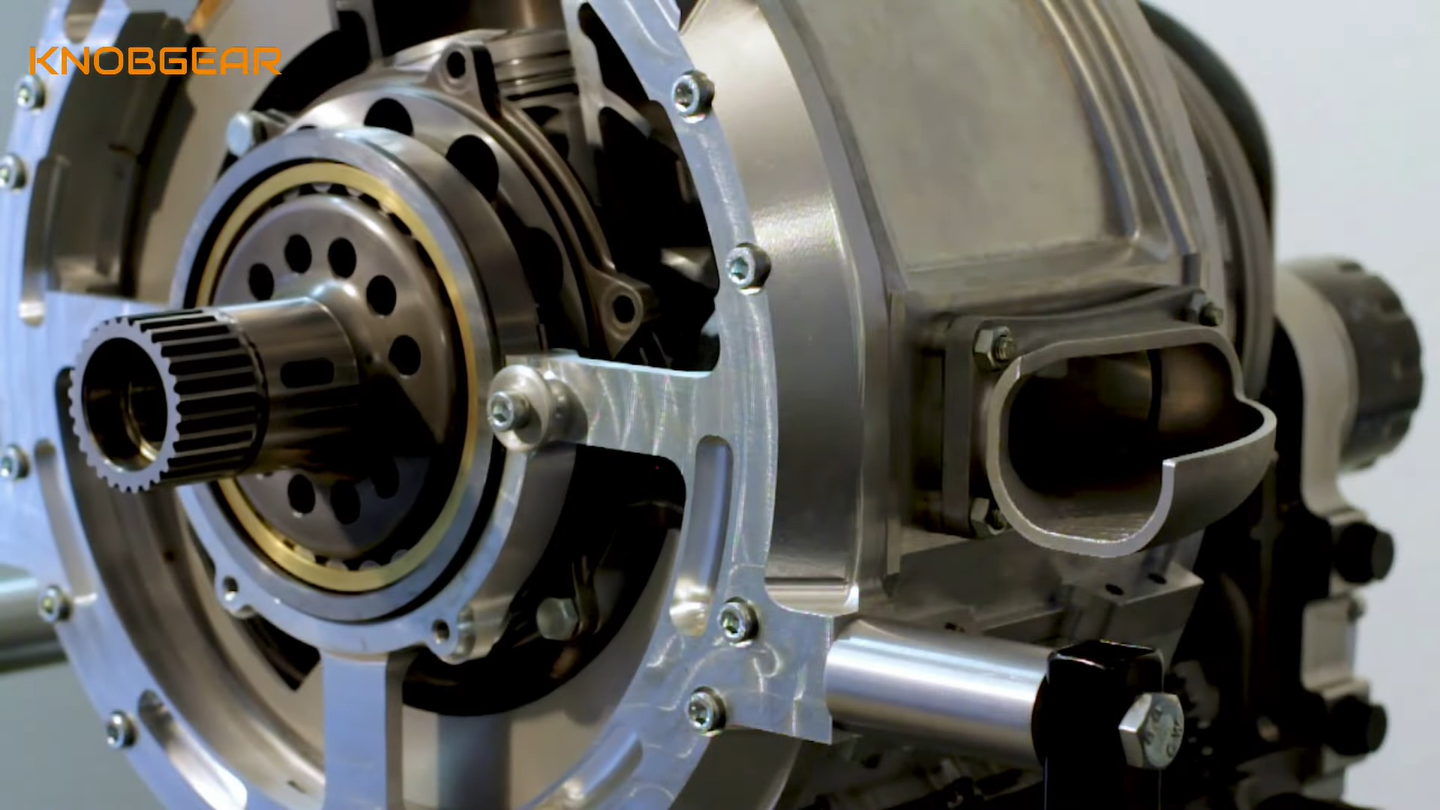

At the core of the Birotary is a set of three cylinders and pistons. These are banked 120 degrees apart, forming a sort of star shape. All three pistons share a central crankshaft. Now here’s the fun part: these pistons and cylinders are housed within a round cylinder block. This entire block spins. As the block spins, each piston is completing its four strokes. Yes, that means the pistons are moving, and the block is moving, too.

While this sounds crazy, it isn’t. Vaclav says that a version of this design already exists in what’s called a rotary engine. By “rotary,” he doesn’t mean Wankel rotary. There is a different kind of rotary engine that’s actually a piston engine.

Here’s what this engine would look like when rotating:

Like this engine, a rotary engine has an odd number of pistons arranged in a sort of radial configuration. What makes this kind of rotary unique is that its crankshaft doesn’t move. Instead, the entire crankcase, with the cylinders and all, rotates around the crankshaft. This kind of rotary engine has been around for more than a century and was often used in aircraft, and sometimes on motorcycles.

Vaclav’s Birotary has a spinning engine block and a spinning crankshaft. That’s different enough, but the weirdness continues as the engine case doesn’t move. To reiterate, the crank spins, as does an inner engine block and the pistons, but the engine case itself is stationary.

Now that you have a picture of the engine, we can see how it moves. If you’re looking at the front of the engine, you’ll note that the crankshaft spins clockwise and the block spins counterclockwise. Thanks to the counterweight at the end of the crank, this opposite rotation helps in canceling out gyroscopic forces and reaction torque.

This is especially important for the expected aircraft application. Propeller-driven aircraft like the Cessna 172 that I fly are subject to four primary factors that cause a left-turning tendency. These are propeller slipstream, gyroscopic precession, P-Factor (asymmetric loading) of the propeller blades, and torque. While a lot of this is caused by the action of the propeller, the engine internals, notably the crankshaft, also matter as the aircraft will want to yaw to the left.

This was a huge deal when the aforementioned old-school aircraft rotary reached its apex of design. These engines got huge, and they had gigantic masses of spinning crankcases in addition to titanic propellers, and thus, a ton of left-turning tendency. Here’s a video of the internal workings of the Birotary:

These left-turning tendencies are counteracted with right rudder input. But of course, a goal of many working in this space. is to reduce these tendencies, either through clever angling of the engine or, in this case, making a unique engine. Since the birotary has two large masses spinning in opposite directions, the gyroscopic motion can cancel each other out.

This is also where the Birotary gets its name from, because there are two major rotating masses in the engine. Look, I didn’t create the name. At any rate, Knob Engines thinks this alone will be a pretty huge deal for light aircraft and make them easier and more pleasurable to fly.

It Gets Weirder

Knob Engines also notes that, by going with this design, the engine technically has fewer parts than a typical piston engine. There’s no valvetrain and its associated components. I’ll let Knob Engines explain:

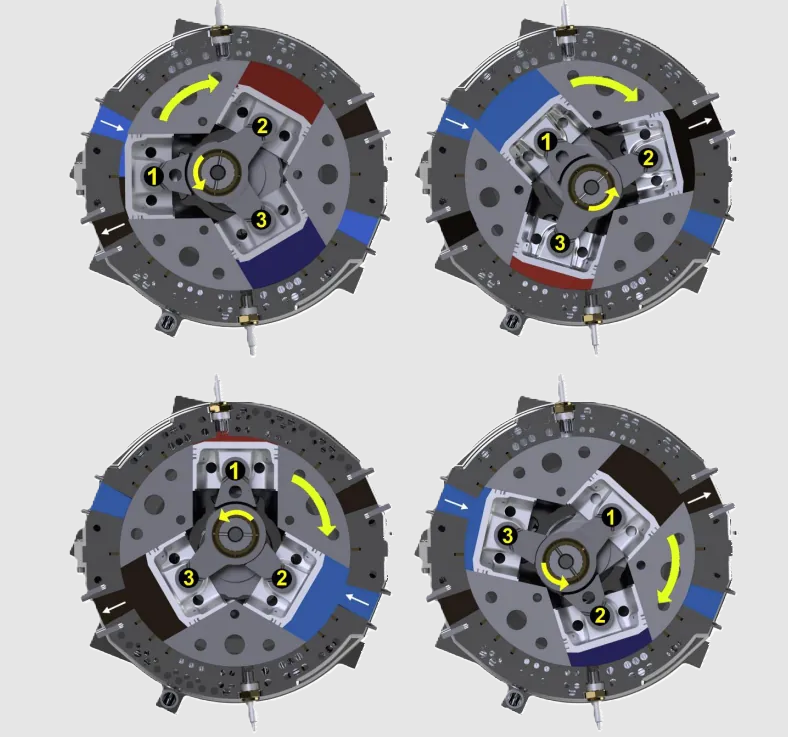

The case is also the cylinder head and has two combustion portions. Each combustion portion is equipped with its own intake and exhaust port, and set of spark plugs. The rotating cylinder block also fulfils the function of slide valvetrain and provides the charge exchange in the cylinders. The cylinder block rotates in opposite direction to the crankshaft. The crankshaft and cylinder block are connected by means of planetary gear set with gear ratio of three (i.e., the crankshaft revolves three times per each cylinder block rotation). This means that for example at 8000 RPM of the engine, the cylinder block rotates at 2000 RPM in one direction and while the crankshaft rotates at 6000 RPM in the opposite direction. The engine completes a four-stroke work cycle once every 720° of relative angle, which means 180° of cylinder block angle plus 540° of crankshaft angle. Each cylinder makes four strokes for every 180° of cylinder block movement, i.e., two full working cycles per block rotation. Figure below shows the engine action trough one four-stroke work cycle.

If that wall of text was too much, I’ll simplify it. The stationary engine case has two intake ports, two exhaust ports, and two spark plugs on opposite ends. It’s like an early two-stroke engine in that the air-fuel mix doesn’t enter the combustion chamber until the piston passes by, allowing the mix in. As for firing order, the crank rotates 180 degrees while the block rotates 60 degrees between firing, for a total relative rotation of 240 degrees. The crankshaft speed maxes out at 7,500 RPM while the block tops out at 2,500 RPM.

You may also wonder why there’s a gear reduction going on, and that has to do with the aviation application. Propellers lose efficiency at high RPM due to drag, so gearing the engine down helps keep the prop in a sweeter zone. In this case, the propeller is attached to the spinning block, so the block must move slower than the crankshaft. Indeed, when I’m climbing out of my local airport, my trainer Cessna 172 is usually buzzing around 2,500 RPM.

Another neat part of the Birotary design is its combustion seals. In a Wankel rotary, you have apex seals at the ends of the triangular rotor. Of course, these seals are subject to all kinds of forces as the rotor spins around, and improving apex seal longevity has been a battle of Wankel engine engineers since pretty much its inception.

This engine is different. Not only is there no Dorito of combustion spinning around in there, but the combustion seals are static, on the stationary engine case. Further, the block is a circle spinning inside another circle. In theory, these seals should last a long time, and the engine should have limited blow-by. Here’s what Knob Engines says about that:

The seal assembly comprises of a side seal, transverse sealing strips, joints and springs. The side seal is divided into circular segments always placed between neighboring transverse sealing strips. The transverse sealing strips pass through the side sealing segments notably reaching over the cylinder bore. This solution prevents excessive bending of sealing strips into the cylinder. Joints are located between the side sealing segments and transverse sealing strips. Each sealing element, including its joints, is equipped with its own spring, which presses it towards the cylinder block. Joints also press the elements, which they sit on.

Placement of sealing elements in the stationary case ensures the stable application of force on the sealing elements and this force is unrelated to engine speed, unlike the Wankel rotary engine. This feature facilitates a very high engine speed and high specific output parameters. All the transverse sealing strips and side sealing segments have a surface or tangential contact with the outer, rotational surface of the cylinder block, which decreases contact stresses of the sealing elements and the outer surface of the cylinder block. This surface contact of the seal also requires less seal lubrication and increases its efficiency and durability. The sealing of the high-pressure portion in the cylinder, i.e. between the cylinder block and stationary case, is multiple in both, axial and tangential directions. It ensures high reliability of this Seal assembly of engine in the connection with the cylinder block solution. The side sealing segments are placed on the edge of the cylinder bore thus minimizing the crevice between the cylinder block and stationary case.

The Competition

The Birotor’s primary competitor will be the Rotax 912S, a favorite among light aircraft builders. The Rotax 912 series has been in production since 1989 and features an air and liquid-cooled flat four design. The 912S has two carburetors, a mechanical fuel pump, an output of 100 horses, a speed reduction gearbox, and 1,352cc displacement.

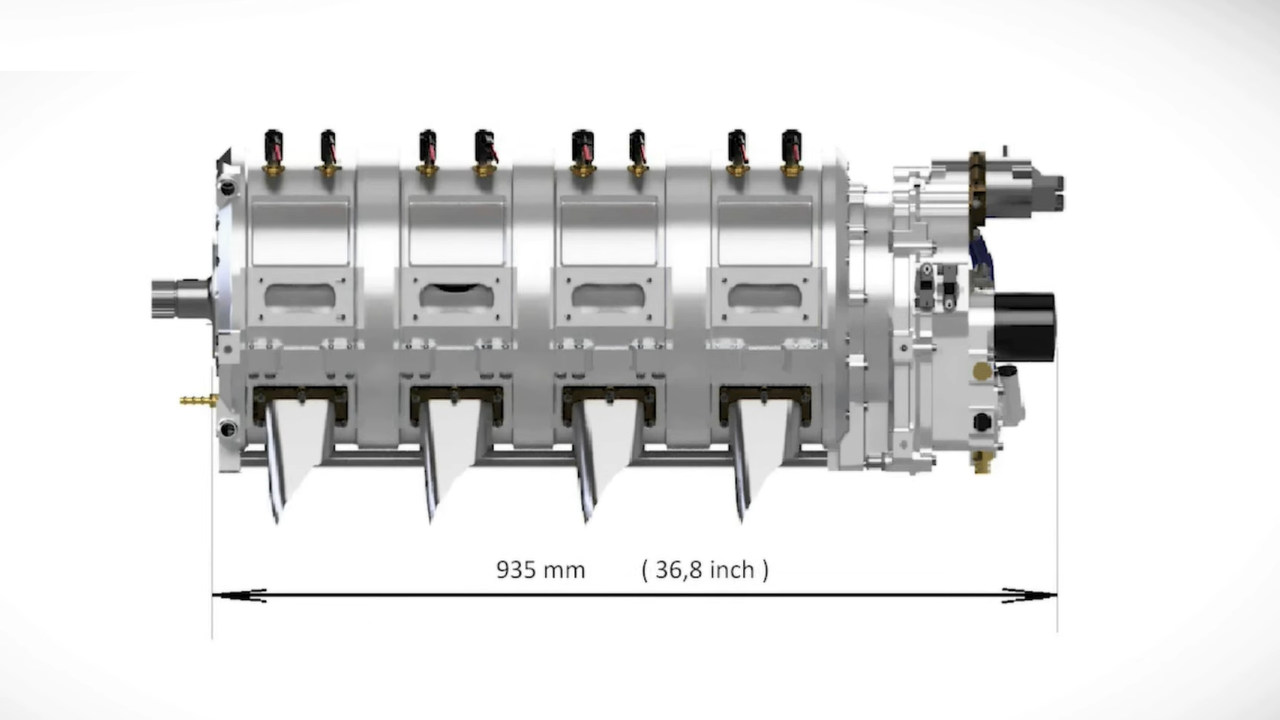

The Knob Engines team is targeting a 750cc displacement, 100 horsepower, and an overall size that’s several inches thinner than a Rotax 912S.

The Knob Engines team has released other important technical notes, too. The engine case is water-cooled, employing liquid channels and a water pump, like your car or motorcycle. The block and its cylinders are cooled through oil.

Speaking of oil, lubrication is handled through an oil pump at the back of the engine, which drives oil through the crankshaft and associated internals. However, Knob Engines says that, at least for now, the engine does use some two-stroke oil in its fuel to lubricate the combustion seals.

As of now, the engine has an absolutely tiny bore and stroke. This is why it can rev to the moon, but also enabled the Knob Engines team to design an engine so small that it could be an effective replacement for a typical piston engine in a light aircraft. However, Knob Engines says that bore and stroke could possibly be increased for other options, but that would make for a bigger and heavier engine.

They Can Multiply

Knob Engines also says that the engine is scalable in perhaps the silliest way possible. If you wanted a bigger and stronger Birotary, you could make versions with multiple spinning cylinder blocks stacked on each other, and each of those blocks could have perhaps as many as 12 cylinders.

Thus, while Knob is focusing on light aircraft for now, the company believes the potential is perhaps endless, and that maybe a Birotary could work in something like a car or a generator. The company is also hoping to hit a time between overhauls (TBO) of at least 2,000 hours, which would be right on the money with the TBO of a Rotax 912.

Of course, it’s too early to tell where this project is going and what impacts it could have in aviation and beyond. At the very least, it’s exciting to see that some engineers have cooked up something truly wild. If you want to know more about this engine, click here to watch a YouTube video by Driving 4 Answers that has even more explanation.

This engine is also yet another example of what I said earlier. The Birotary is complicated and weird, but it’s designed to serve a specific purpose. In this case, it’s to make a tiny engine with few vibrations, lots of power, and great balance. I wish these guys all the luck in getting this to market. Who knows, maybe one day someone might try to swap out their Mazda Miata’s engine with a Birotary rather than a GM LS.

Rotating mass looks immense, so RPM changes are likely not happy. Seals looks to be another issue as we have seen in Mazdas rotary engines. I think we are at the end of an era when it comes to internal combustion engines so I dont see a lot of funding coming.

Get me twelve of these, linked together and shoehorned into a Lada, stat!

I first saw this on Driving4Answers on YT a couple of weeks ago and it was fascinating. A couple of points were made in the video: it’s not big on torque from one aspect (but okay from another), and it really likes to spend its time in a fairly narrow rev range. So with that knowledge in hand and the fact that it is ridiculously smooth with no reciprocating motion, I and quite a few other people in the commentary on the video were all shouting, “Range extender!” Because that’s pretty much the design brief for a range extender in a battery-forward PIH.

But everybody’s observations re: lubrication and cooling are spot-on too. Cooling might be a bit easier when you’re zipping along through the sky at 120mph; tucked down into an engine bay at 60mph, maybe not. Still don’t even know how you’re supposed to plumb the cooling. A test engine running for two minutes is one thing, what about two hours?