If you’ve purchased an American RV at any point in the past several decades, there’s a pretty good chance that at least some part of it was made out of a tropical plywood known as lauan. The RV industry loves this wood because it’s light, moisture-resistant, and crazy cheap. Lauan can be found all over a typical RV, from its walls and floors to cabinetry, and it carries a possible secret. Not only is lauan just an inferior building material in today’s world, but its usage can be shockingly destructive to the world’s rainforests. It’s time for the RV industry to move on, and it wouldn’t even be that hard.

Back in August, reader David P sent me the link to a bombshell of a New York Times story. That report, titled “The Rainforests Being Cleared to Build Your R.V.” by Sui-Lee Wee, is an excellent piece of journalism, and even if you are not interested in RVs, you should read it. In this report, Sui-Lee Wee details how the American RV industry prides itself on its U.S.-built campers, but relies on lauan wood from the rainforests of Indonesia and other regions in Southeast Asia to build the RVs that are sold in the hundreds of thousands of units each year.

The American RV industry markets itself as a steward of conservation and the outdoors. When you take your RV into the wilderness, you’re supposed to leave nature in the condition that you’ve found it in. Preferably, you’d even pick up the rubbish left behind by others and leave the area in better shape than you found it in. As the RV industry touts all-electric campers and greener builds, the subject of where the industry gets lauan from is important.

But even if you do not care about the rainforests of far-off lands, you might care about the other reasons why lauan might not be so great. If you’ve ever owned a camper with lauan walls and floors for long enough, you’re almost certainly acutely aware of what happens when a leak happens and soaks the lauan. If you’re lucky enough to have never experienced it before, water leaks can lead to the lauan delaminating, splitting, and crumbling to pieces. Now, imagine that happening to your RV’s walls and floors. It’s destruction that can cost more to fix than you even paid for your RV, and RVs are often the second-largest purchase people make, behind only a house.

The great news is that the RV industry already has viable replacements for lauan; it just has to commit to them.

Backing Up

To get a better understanding of the current situation around lauan, let’s go back in time.

In the early days of RV construction, builders assembled campers out of whatever material they found and thought would get the job done. In the 1920s and the 1930s, several campers were built out of Masonite, a board made out of steam-cooked and pressure-molded wood or paper fibers. Its name comes from its inventor, William H. Mason, and Masonite was used for everything from RV walls to home furniture.

Other trailers in the pioneer era of RVs used plywood covered in aluminum sheets, sealed plywood, hardwood, or were built out of metal. America’s largest producer of campers in the 1930s, Covered Wagon, built its trailers (one is pictured above) with frames made out of white oak, floors of plywood, and wood-framed walls draped in a leather-like material for exterior cladding.

Some companies, like Bowlus, Airstream, and Spartan, figured out that they could build a long-lasting trailer by ditching wood construction for building campers with a riveted aluminum body like an aircraft has. Even homebuilt teardrop campers would go aluminum after World War II, thanks to cheap surplus aircraft aluminum. Later, a new wonder material would come onto the RV scene, fiberglass, which revolutionized the super-lightweight end of the RV market.

However, as the International Wood Products Association claims, a major breakthrough in RV construction was made in the 1970s:

The RV industry has been using imported woods like lauan plywood since the 1970’s, prized for its strength, unique thin construction and affordability. “Lauan is such a great material for the industry because you can get it in thinner sheets than domestic plywood,” says [Bruce Hopkins, vice president of standards and education for the Recreation Vehicle Industry Association]. “Thinner sheets allow manufacturers to bend it for interior contours, so they can provide the consumer with something other than just a square box. It’s also very easy to laminate with fiberglass and aluminum for exterior walls, and with vinyl and other materials for interiors. In each case, the lauan plywood provides the combination of strength, thin construction and lighter weight, all critical in RV construction.

Thanks to lauan, RV manufacturers no longer had to experiment with whatever materials existed in America. Now, these companies could use this imported wood for everything from RV walls to RV cabinetry, and know that what they built should be strong enough for the job.

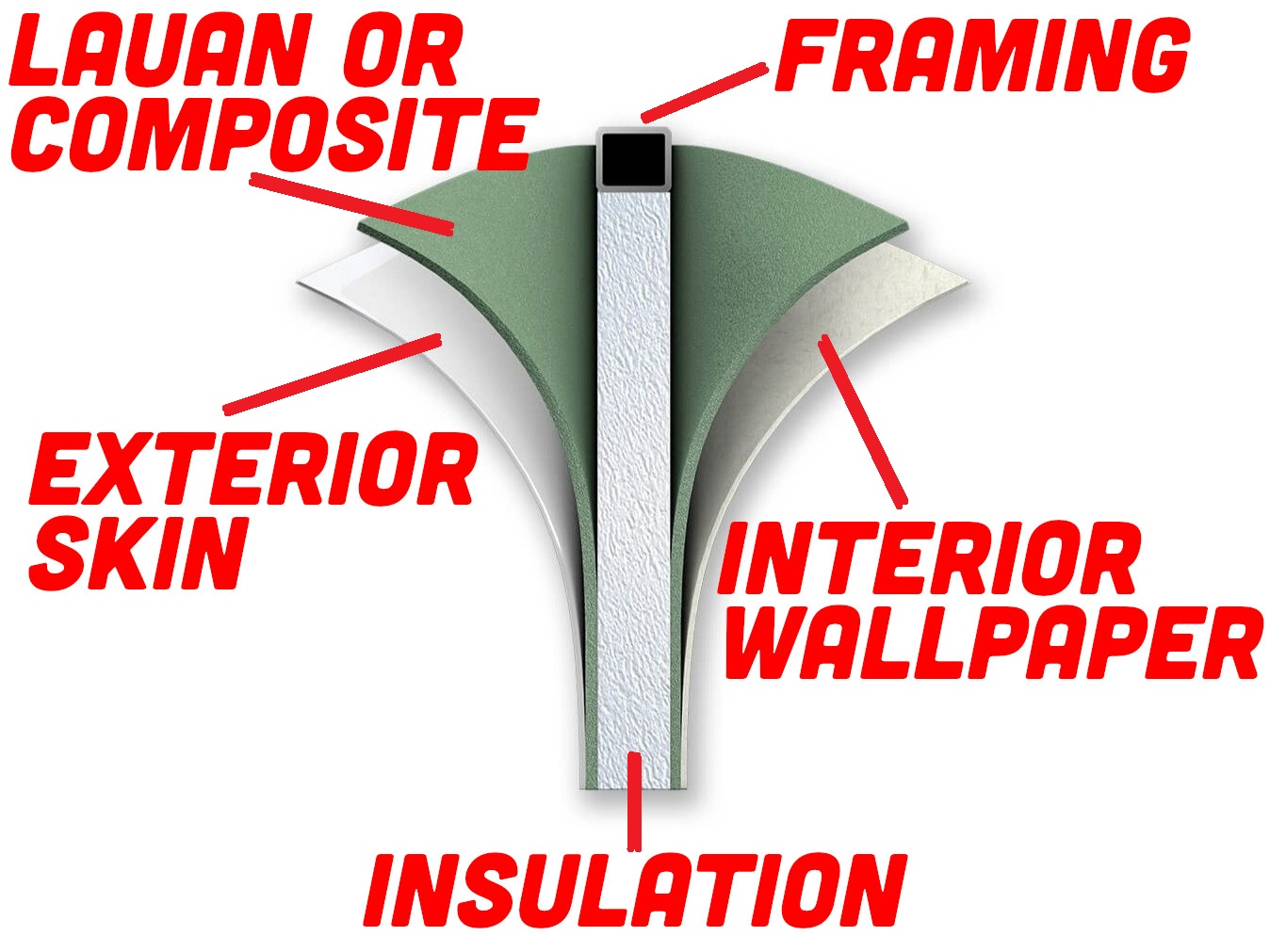

As Hopkins noted above, one of the most common uses of lauan is to make a bonded sandwich for walls. A common construction method involves a lauan sandwich with aluminum or fiberglass sheeting outside, a layer of lauan, a layer of insulation, and another layer of lauan. This sandwich is pressed and bonded together, and when finished, the sandwich is supposed to act as one solid structure. When you buy a typical camper, the interior walls are lauan with a sort of plasticized wallpaper finish on top.

The Money In Lauan

When lauan works, it does a decent job. Indeed, intact lauan sandwiches are strong and lightweight. It’s also a very affordable material for the RV industry to use to crank out tons of RVs each year. Historically, the RVIA says, the RV industry benefited from the Generalized System of Preferences, a trade program described by U.S. Customs and Border Protection as:

GSP is the largest and oldest U.S. trade preference program that provides nonreciprocal, duty-free treatment enabling many of the world’s developing countries to spur diversity and economic growth through trade. Economic development is promoted by eliminating duties on thousands of products when imported from designated beneficiary countries and territories. Authorized by the Trade Act of 1974 and implemented on January 1, 1976, GSP is a preferential trade legislation that is subject to Congressional re-authorization.

Basically, RV manufacturers used GSP to import lauan from Southeast Asia for cheap. When the GSP program lapsed at the end of 2020, RVIA says, the RV industry had to pay $1 million to $1.5 million in import duties each month for the lauan it was importing. Congress is in charge of reauthorizing GSP, which extends the program another two or three years.

In an unexpected move, Congress did not reauthorize GSP after its expiration, yet, that hasn’t stopped the RV industry, and it continues to import lauan despite the apparent cost. RVIA, along with reportedly more than 300 groups, including the Heritage Foundation, the American Apparel & Footwear Association, the Coalition for GSP, and more, have been lobbying Congress to reauthorize GSP. In RVIA’s policy agenda, the representative for the RV industry specifically targets lauan from Indonesia as a product it wants to be able to import duty-free.

The New York Times Report

That brings us back to the excellent reporting by the New York Times. For total clarity, we will be using direct quotes here. Journalist Sui-Lee Wee starts off the story with a grim anecdote:

Word spread fast that heavy machinery had arrived in the ancient rainforest near the Indonesian village of Sungai Mata-Mata, an expanse on the western edge of the island of Borneo that is home to orangutans, clouded leopards and sun bears.

Flouting the law, the excavators began digging trenches to drain the area’s protected wetlands. Then came the logging crews, which cut down woodlands the size of more than 2,800 football fields, in just a few days. It was an apocalyptic sight, said Samsidar, a regional forestry official who goes by one name, recalling the devastation he encountered two years ago. “The trees had turned into piles of wood.”

Not just any kind of wood, though. The trees were meranti, a species found mostly in Indonesia and other parts of Southeast Asia, and their tropical hardwood is of particular interest to one industry in the United States: manufacturers of motor homes.

If you thought that was bad, it gets worse. According to the NYT, since 2020, the United States has brought in more than $900 million worth of lauan, mostly from Indonesia.

The NYT report continues by noting that tens of thousands of trees were felled in Indonesia last year alone just to supply America with lauan. Reportedly, all of those trees were in rainforests, and the deforestation was rubber-stamped by local governments.

Here’s how the RV industry responded to the report, from the New York Times:

Among the big R.V. makers, Thor Industries says that its suppliers are forbidden by U.S. law to buy illegal timber, and Winnebago says that it is committed to preserving the planet.

Thor added that it was not aware of any deforested wood in its supply chain. Winnebago referred questions about the origins of its lauan to its supplier, Patrick Industries, an American company, and the R.V. Industry Association; neither of which responded to requests for comment. Nor did Forest River, another big R.V. maker.

RVIA effectively argues that it has no choice, from the report:

“Without access to lauan, manufacturers would be forced to use thicker, heavier materials that reduce livable space, impact fuel efficiency, and compromise the structural design and safety of the R.V.,” the R.V. Industry Association said in a letter to the Trump administration in April while arguing against new tariffs on the plywood.

“In short,” it added, “lauan is not just a preference — it is a functional necessity integral to nearly every R.V. built in the United States.”

If you check out RVIA’s federal policy agenda document, it makes the same argument that there is no domestic replacement for lauan.

I have also reached out to America’s largest RV manufacturers, Forest River, Thor Industries, and Winnebago, for comment on the findings presented in this report. I also asked if these companies might be considering moving away from lauan in the future.

As of publishing, I have not heard back from these manufacturers.

There Are Other Ways To Build A Camper

I take some issue with the industry’s assertion that it has no choice but to use lauan. Let’s bring up what RVIA said again:

“Without access to lauan, manufacturers would be forced to use thicker, heavier materials that reduce livable space, impact fuel efficiency, and compromise the structural design and safety of the R.V.”

Thor Industries’ flagship brand is Airstream, a company that is iconic for building the bodies out of its campers out of aluminum. Many RV owners, myself included, would argue that Airstream’s aluminum bodies are actually better for structure than lauan sandwiches and wood framing are. It’s also not like an Airstream weighs a million pounds, either.

As any longtime RV owner can tell you, lauan also isn’t the best for longevity either. Yes, lauan is very strong when your camper is perfect. But once water starts getting in from one of the countless seals or holes that can give way, the damage can be catastrophic. Lauan has a tendency to delaminate with its exterior skin in these scenarios, and if left uncured for long enough, the lauan will lose structural integrity and fall apart.

Water damage isn’t even the only situation that will cause lauan to fail, either, as a defective bond can cause lauan to delaminate even without the presence of a water leak.

I have personal experience with this, as this is exactly what happened with my family’s 2007 Adirondack 31BH. Water leaked in from a bad roof seal over the bathroom and destroyed the lauan so badly that the wall blew out, and the floor was cracking under my feet. My family paid $7,500 to have that fixed, and then my family paid another $8,500 to have the lauan replaced for a second time after another part of the trailer’s structure failed due to water damage.

The RV industry has already invented a partial solution for this. Azdel, a product of Hanwha Azdel, is a composite wall structure material (a blend of polypropylene and fiberglass) that has been on the RV market since 2006. Azdel does not solve water leaks, but it does have solutions for the symptoms of water leaks, namely, a composite isn’t going to rot out and disintegrate like compromised lauan can.

Unfortunately, while Azdel has seen wide use in the RV industry, it is still used primarily for walls, with lauan still showing up in flooring and cabinetry, even in trailers that use Azdel. Likewise, the campers that use Azdel panels can still have rubberized roofs. These trailers are still subject to the same water leakage problems of the campers of the recent past, only now, the walls won’t split apart as the rest of the camper rots out.

So, Azdel is not a magic cure for water leaks. However, the use of Azdel does mean that no tree has to be harmed. As for the rest of the camper, the industry has shown it is capable of moving away from lauan. I have personally toured RV designs that made great use of metal, composites, plastics (like the LIV below), and fiberglass to great success for flooring, roofs, and interior furniture.

If you must use wood, there are more sustainable sources for it. According to the New York Times report, sustainable lauan is apparently a thing, too, from the report:

Conservation groups say R.V. makers are only focused on price and do not have policies to responsibly source lauan. This allows deforested timber to taint the industry’s supply chains, they say. Sustainably grown lauan now is plentiful in Indonesia and while it goes for about 20 percent more, Earthsight, a group based in Britain, argued that outfitting an R.V. with only that kind of wood would have a negligible effect on its price.

“Nature-loving R.V. owners would surely be more than happy to pay this tiny price,” said Sam Lawson, Earthsight’s director.

I would love to see a future where America’s RV industry ditches lauan, or at the very least, minimizes its use. I have a feeling that nobody is going to miss lauan delamination or paying thousands to fix this stuff years down the road. Better materials exist; they just have to be used.

Now, I’ve become somewhat of a harbinger of doom to some RV manufacturers, so I want to clarify that I do not hate you! I have spent much of my life championing RVs. I am a person who would rather stay in an RV than any Holiday Inn. I love applauding industry innovation and the bright minds who keep RVs great. I enjoy every RV show that I go to. Shoot, my longest-ever story was a 6,000-word interview with the CEO of an RV company. However, I do think the industry has room to improve, and its heavy use of lauan is one of them.

This is a situation where I think the industry has a lot to gain and little to lose. Sure, a camper made out of composites might have a different price and a different weight, but I’d be willing to bet customers will love the longevity. The rainforests will love you, too!

Top graphic images: Mercedes Streeter; depositphotos.com

I think it’s simply time for Mercedes to sell half of her remaining cars and start an RV-building business with the money.

Should be enough, given how cheaply made most are nowadays. And she certainly has the knowledge of what needs to be improved.

I don’t see how the RV industry could make any kind of environmentally friendly claim with a straight face. It’s horribly inefficient to live in a home that is designed to be moved around. Also, considering how poorly made today’s campers are, they’re a gigantic example of disposable consuemer goods. Maybe if one is well cared for it will last 30 years, but at the cost of expensive repairs.

I already knew that so many RVs and campers are essentially very, very expensive disposable toys because of their construction…but I didn’t realize the extent of the harm that was being done in harvesting the raw materials. That was a fascinating and disturbing piece; thanks for educating us, Mercedes.

It sure would be nice if everyone could afford an aluminum trailer, but alas, that is never going to happen. There’s a little bit of armchair coaching to Mercedes’ assertions here. After reading the entire NYT piece, I concluded that the sustainable lauan option is probably the best compromise. And while it’s unconscionable for the RV manufacturers to not purchase sustainable supply, I believe they otherwise probably have some idea of what they are doing with respect to construction methods (but clearly no concept of quality control). Essentially, if it were as easy as just making a better choice, I suspect someone would have made that choice and succeeded, but that hasn’t yet happened, so it’s perhaps not as simple as just choosing another equal or better option.

Construction techniques in the RV industry seems to run on inertia. There are more durable alternatives to wood, such as corrugated plastic.

All RVs leak. Using a material such as wood inside of a product where it’s 100% certain to get soaked in water is engineering malpractice.

Plastic has problems of its own, to be sure. Most is not recycled, though much of it could be.

Great story, Mercedes. I don’t understand what draws people to stick-built RVs. Conceptually, I like the idea of a Scamp or Casita camper, but then I would need to store it, which immediately becomes an issue. I always come back to the fact that I go camping to be outside.

Purchase price. That’s why. And travel trailers are a legit choice. Not everyone can hike a trail. Where we go camping, we see a lot of larger family groups who get together every year. For them it’s not as much about camping, as it is an annual family reunion. I can respect that.

Non-paywall link for those who want to read the full NYT article:

http://archive.today/NT73h

It’s selfish of me because I have no desire for a camper of any kind, but if most of the RV industry went under I wouldn’t shed a tear. They kind of all completely suck and RVs rival boats for vehicles that sit unused for the longest period of time.

A co-worker bought a used pop-up camper trailer and spent $500 repairing it. Then he realized it was too small for his family. So he gave it away and bought a larger one. Then he needed a more powerful truck to tow that. So be bought a bigger truck. Then the bigger camper sat unused for 50 weeks a year while he’s paying money to store it. And of course he doesn’t need the larger truck if he doesn’t need to pull the trailer 50 weeks a year. I should ask him what happened next.

It’s kind of insane how much the cycle repeats. Really shows the human tendency to go “naw, that won’t happen to me, I’ll be different.”

Then there is the other side of that coin. 500K people live full time in an RV.