The Union Pacific Railroad used to be obsessed with power. The railroad spent decades searching for and developing one locomotive to rule them all. This search resulted in icons like the Big Boy and the gargantuan EMD DDA40X. It also led to fascinating failures. One of them was Union Pacific No. 80. This locomotive was a mammoth creation, stretching out the length of a Boeing 747-200. It also made 7,000 horsepower with help from a turbine that burned coal, at the expense of slowly killing the engine every time it ran. This locomotive was a mammoth creation, stretching out the length of a Boeing 747-200. It also made 7,000 horsepower with help from a turbine that burned coal, at the expense of slowly killing the engine every time it ran.

Union Pacific No. 80, later renamed to No. 8080, was a one-off derivative of perhaps the craziest locomotives to ever pull trains, the Union Pacific Gas Turbine-Electric Locomotives, or GTELs. As I wrote in 2022, these locomotives sported gas turbines that burned Bunker C fuel and made around 8,469 horsepower, depending on generation, making them some of the most powerful internal combustion locomotives ever built. The GTELs were thunderously loud and fired a jet blast that was so hot and so fast it had the capability of cooking birds in mid-flight and melting bridges.

There is a variant of the GTEL that is technically slightly less crazy, but is still somehow absolutely insane by any standard. In the 1960s, Union Pacific made an experimental derivative of the GTEL that traded the bunker fuel for coal. By making a turbine run on coal, Union Pacific managed to make a locomotive that was so unreliable that it didn’t even last a hundredth of the miles of the GTELs before the railroad gave up on it.

But why did Union Pacific try to shovel coal into a turbine, and why was it so terrible?

The Common Solution To More Power

Today’s railroads pretty much all use a similar method to produce the power required to pull a train. They take powerful locomotives and lash them together into a giant chain until the desired “consist” (the whole train, locomotives and cars) is created. If you ever pay attention to the freight trains that roll through grade crossings in America, it’ll be common to see freight trains with two, three, four, or even five locomotives pulling and pushing a train. I have seen one train with eight locomotives running through a local town here in Illinois.

Multiple-unit operation is a genius scheme that allows operators sitting in only one cab to control an entire line of locomotives. Distributed power then allows for one or multiple of these locomotives to be placed just about anywhere in the consist, but still be controlled by the operators in the locomotive up front. Some of America’s iconic multiple-unit applications involved what were known as ‘A’ units, or a full locomotive with a cab, and ‘B’ units, which were locomotives without cabs that were controlled by the engineers in the ‘A’ units.

These concepts have been around for much of modern railroading history, with multiple-unit control dating back to the 1890s. Even fully-electric locomotives benefit from this concept.

Nearly a century ago, multiple-unit operation did carry some downsides that some railroads didn’t like. Back in those days, trains had gotten so long and so heavy that two steam locomotives often had to pull trains up tall hills. Early diesels weren’t particularly powerful, either, which meant that a bunch of them had to be linked together to do the same work. All of this costs railroads money in fuel, maintenance, and crews. It also cost the railroads valuable time because the time spent assembling these trains was time the trains were not running down the rails.

An Unquenchable Thirst

The Union Pacific took perhaps the boldest steps to solve these problems. The railroad figured that it was possible to make one locomotive do the work of two, thus saving time and money. This would become quite an obsessive quest, as I have written before:

Over a century ago, Union Pacific grew an unquenchable thirst for more power. As Trains Magazine writes, Union Pacific’s Overland Route between Omaha, Nebraska, and Ogden, Utah was largely flat and easily traversed by the steamers of the day. The problem was east of Ogden with the Wasatch Range. Trains traveling eastbound had to climb 1.14 percent grades, which doesn’t sound all that steep, but that’s a big deal for large, heavy trains running metal wheels on metal tracks.

The Wasatch Range had been a thorn in the Union Pacific’s backside since the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869. The railroad’s solution to the steep grade was inelegant and required locomotives to be lashed up before they finally produced enough grunt to haul loads up the grades. However, double-heading trains and using helper locomotives took time, slowed operations down, and cost the railroad money. What the Union Pacific really wanted was one locomotive that could do it all.

So, throughout the late 1800s and early 1900s, the railroad commissioned ever larger and more powerful locomotives in its obsession with beating the Wasatch Range. In 1936, Union Pacific fired another salvo at the range in the form of the Challenger 4-6-6-4 locomotive, which put up a good fight, but still required backup when hauling 3,600 short tons of freight through the range.

Union Pacific found itself in a pickle in the 1930s as it had stretched the era’s steam technology to its limit. In 1936, Union Pacific established the Research and Mechanical Standards Department to build a single locomotive capable of conquering the Wasatch without help.

This quest would eventually lead to the creation of the iconic Big Boy, the largest steam locomotive that’s still in operation. The Big Boy, which entered service in 1941, wasn’t the biggest or the most powerful steam locomotive ever made, but it is a good representative of what the apex of steam technology looked like.

Experimentation

Since the railroad was already pushing the limits of steam, researchers started looking into other technologies. One of these experiments was the steam turbine locomotive, from my retrospective:

The railroad started experimenting with turbines back in the late 1930s; in April and May 1939, the railroad tested a pair of steam turbine-electric locomotives that were produced in a collaboration with General Electric. At the time, train history site Utah Rails notes, Union Pacific was looking for a replacement for steam and something more advanced than the diesels of the day. The steam turbine-electric locomotive used an oil-fired boiler to produce steam to turn a turbine. That turbine was paired with a generator, and tractive effort was achieved through electric motors. The locomotives looked on the outside like the diesels of the day.

Ultimately, the steam turbine-electric locomotives proved to be unreliable, sometimes encountering failures that required other kinds of locomotives to finish the journey. The turbine-electrics never entered regular service and were returned to GE in June 1939. UP kept the collaboration going for another two years before deciding to stop chasing the technology. Right around this time, the railroad entered its now famous Big Boy steam locomotives into service, and it wouldn’t even be a decade before Union Pacific would flirt with different technologies for locomotives again.

In the mid-1940s, Union Pacific found itself wanting more once again. In 1946, the road had 154 diesel-electric locomotives, with zero running freight. The problem was that the diesel-electric locomotives of the era, like the EMD F3 and Alco FA, made only 1,500 horsepower. This was nothing compared to something like a Big Boy, which had up to 7,000 horses on deck and a 135,375-pound tractive effort. UP would have to lash several diesels together to equal just one steamer. I bet you see where I’m going with this.

Union Pacific wanted a singular locomotive that pulled like a steamer did with modern technology. The problem was that diesel fuel was expensive in the 1940s, and diesel engines weren’t really reliable just yet. If UP did manage to make a crazy, powerful diesel, it would cost so much to run that its costs would negate its benefits.

Bringing Aviation To The Rails

After World War II, General Electric rebooted gas turbine development after learning some lessons from aviation during the war. The turbine engine had big promises for railroading. In theory, a turbine could make much more power than a 1940s diesel. General Electric joined forces with the American Locomotive Company, and in 1948, it put a gas turbine-electric locomotive into real-world testing with the New York, Chicago and St. Louis Railroad and the Pennsylvania Railroad. Alco-GE number 101 looked like a diesel, but punched out three times the power at 4,500 horsepower. The unit would later be transferred to Union Pacific, which renumbered the locomotive to 50. UP was so impressed with No. 50 that it returned to Alco and GE to order 10 more.

Here’s how a GTEL worked, from my previous reporting:

How these locomotives work is similar to a diesel-electric, but with a different kind of engine. Union Pacific’s GTELs used a GE Frame III turbine engine to drive a generator. That generator produced electricity, which found its way down to the traction motors.

Another difference between a diesel and the turbine units was the kind of fuel used. The GTEL units were fueled using heavy fuel residual oil. Documents from Union Pacific and General Electric note that fuel to be Bunker C, a black heavy fuel that has the consistency of molasses at room temperature. This meant that the fuel had to be heated to provide a reliable flow to the turbine. To achieve this, heaters were installed into the locomotive’s fuel tanks to warm the sludge to 200 degrees.

The residual oil was also too heavy for the turbine to start. Thus, the starting procedure involved using the locomotive’s auxiliary diesel generator to spin up the turbine. The turbine would then start on diesel. Then, after the turbine was running fast enough it would be fed the heavy fuel oil.

Three generations of GTEL were built. The first-generation locomotives (above), numbered 51 through 60, entered service beginning in 1952.

The locomotives featured a 4,500 HP turbine located in the locomotive body. The first-generation locomotives initially carried 7,200 gallons of bunker fuel in a frame-mounted tank, which was enough fuel to travel between Green River, Wyoming, and Ogden, Utah. UP would later repurpose 24,000-gallon steam locomotive tenders to be towed behind the GTELs, providing enough range for the trains to run the 990-mile route between Ogden, Utah, and Council Bluffs, Iowa.

The second-generation locomotives (above), numbered 61 to 75 and delivered beginning in 1954, were mechanically similar to the first generation. Instead, the biggest change to these 15 locomotives was the addition of crew walkways alongside the locomotive body. The second-generation GTELs were also used to successfully develop multiple-unit control for the turbine locomotives.

Finally, there were the comically insane third-generation GTELs, which entered service in 1955. From my story:

Numbered 1 through 30, the final run of UP GTELs saw a major design overhaul. The previous two generations of GTEL featured the locomotive and a tender. These third-generations? They came in three sections. Up front was a control cab that contained a Cooper-Bessemer FWB-6 850-HP diesel engine. This engine provided auxiliary power, as well as power to move the control unit around in a yard. Bringing up the rear was one of the 24,000-gallon tenders. And in the middle? A GE Frame 5 turbine kicking out 8,500 horsepower at an elevation of 6,000 feet. At sea level, it’s believed that the turbine could do even better, putting out 10,000 horses. However, it’s noted that the generator was rated for 8,500-HP.

That massive gas turbine unit powered four generators, which in-turn powered 12 traction motors. The control cab had six motors, as did the turbine unit. This turbine still fed off of fuel oil that needed to be heated, and this was done electrically in the 24,000 gallon tender.

The Illinois Railway Museum says that the whole 165-foot, 11-inch consist weighs in at 849,248 pounds. Though some estimates say that loaded down with fuel, these are well over a million pounds. No matter how you look at these locomotives they’re simply gargantuan. But for more numbers, a third-generation GTEL produces 240,000 pounds starting tractive effort, and 145,000 pounds at 18 mph. That is up from 105,000 pounds in the previous generation.

As I wrote in my story, these absolute monsters practically terrorized America. They were so loud that they were allegedly banned from entering cities in California. Meanwhile, they burned fuel at 1,400 degrees Fahrenheit and exhausted it at 150 mph and 850 degrees. How hot was that? If a bird was unlucky enough to fly through the jet stream, its poor life was over. Also, the locomotives had a knack for flaming out, and if they did so under an overpass, the locomotive was hot enough to melt pavement.

Oh, and the turbines were shockingly thirsty, burning twice as much fuel as a diesel would on the same routes. The locomotives burned a gallon of fuel every 360 feet. Yet, somehow, running the GTELs actually helped UP’s bottom line. Bunker fuel was so cheap, and the turbines were so reliable, that the GTELS were cheaper to run than a bunch of diesels.

The Achilles’ Heel

The turbines were largely reliable, with Union Pacific claiming that 25 GTELS traveled six million miles over four years. Over that time, the turbines racked up 227,950 running hours. One turbine alone clocked in 17,266 hours. But the turbines did have one main Achilles’ heel, and it was erosion.

A major issue of burning of Bunker C was that the fuel’s ash content in its gas flow–– containing sodium and vanadium — corroded and eroded combustor cans, nozzle vanes, and turbine blades. A GTEL’s turbine nozzles and first-stage blades were made of a high-nickel Nimonic 80A alloy, a material designed for intense heat. To slow this erosion down, engineers used Epsom salt and water in a fight to neutralize the effects. The result was a time between overhauls of 4,000 and 5,000 hours for each turbine.

Feeding Coal Into Turbines

There is a twist to the GTEL story that I have not written about before, and it’s that GE never intended gas turbines to be the end of the line of development. In 1949, GE hoped that the success of the gas turbine-electric locomotive program would lead to the development of a successful means of getting a turbine to burn on absurdly cheap coal rather than bunker fuel.

According to Popular Science in 1948, some researchers had seen a coal-burning turbine as the holy grail of coal-burning locomotives. Since 1944, nearly two dozen organizations have been trying to figure out how to get aviation turbines to run on coal. The promise was that a coal-fired turbine would make more power than a diesel with greater efficiency and a lower cost. There were also tons of coal just sitting around America, or fuel just sitting there, waiting to be used. Turbines were also thought to be a step toward a future where trains would be powered by nuclear reactors.

However, there were always two fundamental issues with this idea. The first was that the coal had to be ground down into a fine powder so it could be gasified and burned by the turbine. The second was that the ash content of coal is even worse than the ash content of bunker fuel, which meant that a turbine running on coal would more or less eat itself alive as it eroded its own blades away into nothing.

In 1948, nine railroads and four coal producers sponsored a $2,800,000 development program to figure out how to solve these two issues.

Back then, a developer of coal turbine technology was John I. Yellot of Bituminous Coal Research. Yellot had this idea to get coal to burn in a turbine, from Popular Science:

In Yellot’s version of the coal turbine, crushed coal will be “fluidized” by conveying it, under high air pressure, to a “coal atomizer.” Here, as the coal passes through a small nozzle the rapid expansion of the air trapped inside it will literally blow it apart to form a powder as fine as tale. The finely powdered coal and high-pressure air then will be fed to a combustion tube to be burned and transformed into hot air and gases.

Any sand and grit in the hot gases will be removed by a fly-ash separator similar to the centrifugal filters used on Army tanks to whirl dust out of the air-intake tubes of their engines.

Control of the turbine’s speed would be handled through controlling the flow of coal and air. Yellot said his design would net 20 percent efficiency, which was said to be better than burning coal to generate steam and better than burning diesel.

Union Pacific Pulls It Off

It would take until 1962 for the first direct coal-fired turbine-electric locomotive to hit the rails. In 1962, UP President A.E. Stoddard said that UP had partnered with Bituminous Coal Research, Alco Products, and General Electric for coal turbine development. UP’s scientists and Bituminous Coal Research’s scientists had spent years trying to solve the turbine erosion problem.

A major reason why UP was so interested in spending years developing a coal turbine had to do with the fact that UP had massive coal reserves from its steam days. Then there was the expectation that the coal turbine locomotive would be more efficient than diesel alone while providing more power.

The locomotive trainset was a bit of a kitbash. The lead locomotive A-unit was a rebuilt Alco PA-1 diesel-electric locomotive, while the B-unit chassis was from a Great Northern W-1 electric locomotive that the Great Northern Railway had scrapped. The prime mover in the lead locomotive came from the PA-1 and was an Alco 16-244G, a 174.4-liter V16 diesel rated at 2,000 horsepower.

Inside the B-unit was one of the turbines from a GTEL. The second unit, which was 101 feet long, contained a 5,000 HP turbine, generators, 12 axles (eight of which were powered), and an auxiliary diesel engine, which drove a 500 kW alternator. That was the power required to process the coal on the train itself so that it could be burned by the turbine. The video below is a great clip of the sound of a GTEL.

Dirty Jobs

A December 17, 1962 piece by Railway Age explains how the coal processing equipment worked, from Railway Age:

When the turbine is operating on coal, nugget-size pieces (about 1 by 2 in.) move through crushers and a pulverizer which reduces them to particles small enough to move in a fluidized state when introduced into an air stream. In this state it has much the same handling characteristics as a liquid. The crushed coal is stored in a 2.5-ton bin in the processing compartment of the tender. Two coal pumps meter crushed coal to the two pulverizers in accordance with turbine requirements.

With this system, the amount of pulverized fuel is kept to a minimum and it is pulverized only as required. After the coal is ignited in the combustors. the gases pass through ash separation equipment where non-combustible abrasive ash is drawn off to reduce wear on turbine buckets.

Railway Age notes that the turbine came from a first or second-generation GTEL, which made 4,500 HP before the conversion to coal power. The modified turbine started on diesel fuel first, then, once it reached idle, it changed over to coal.

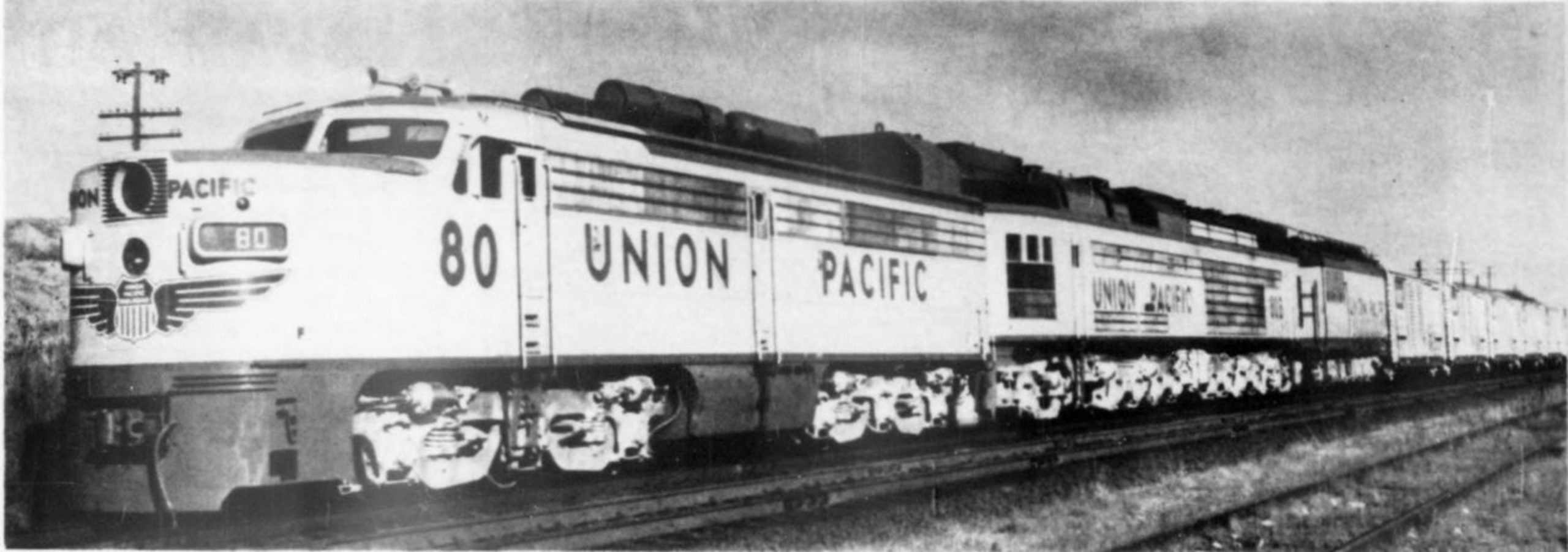

The locomotive setup was finished off with a repurposed tender from Challenger steamer No. 3990. This tender held 61 tons of coal, which UP said was good for a 500-mile trip before refueling. This locomotive was seen as a revolutionary step forward at the time. Before UP No. 80, a coal-fired turbine had only been run on a test stand. But here that research was in the flesh on a running and driving locomotive.

It was a beast, too. The diesel in the A-unit combined with the turbine in the B-unit to equal 7,000 horsepower. Its length was also impressive, measuring in at 214 feet to 226 feet long, depending on the source. For reference, that’s roughly the length of a Boeing 747-200. The turbine unit produced 127,275 pounds of tractive effort with the lead loco providing another 60,832 pounds. The whole thing weighed 733,000 pounds.

No. 80, which was later renamed to No. 8080 when UP received its first EMD DD35 diesel-electric locomotives in 1963, hit the rails for real-world testing.

How To Make A Gas Turbine Worse

Unfortunately, the Union Pacific learned quickly that the various researchers involved in the project did figure out how to get a turbine to run on coal, but did not figure out the accelerated erosion issue.

As UP learned, firing coal dust through an aviation-style turbine results in severe turbine blade erosion as the coal sort of sandblasts the turbine. The coal eroded the turbines even faster than Bunker C, which was already problematic. Soot build-up was also high. This basically meant that, from the moment the turbine was switched from diesel to coal, it steadily ripped itself apart.

The process to refine the coal from one-inch chunks into a fine powder was also a complicated process that added extra steps that the regular GTELs didn’t need. As it was, the coal turbine locomotive needed an extra diesel engine just to run the equipment to pulverize the coal. The process also wasn’t particularly refined, either, and ash that the separator did remove from the turbine was shot straight into the sky.

How bad was it? UP No. 8080 traveled only 21,848 miles over only 20 months on the tracks, racking up only 488 hours of runtime before the railroad threw in the towel. That was a disappointment compared to the regular GTELs, each of which easily rolled more than 1 million miles in service.

UP kept No. 8080 at a yard in Council Bluffs, Iowa, for a few years before striking the locomotive from the record in 1968. The A-unit was sent to live with EMD while both the turbine unit and the tender were scrapped.

Amazingly, the coal turbine idea didn’t die with UP. In the aftermath of the 1973 oil crisis, the U.S. Department of Energy and General Electric looked into running locomotives on coal slurry. Fortunately, the study was a dead-end and never produced a working engine.

The End Of UP’s Quest

While Union Pacific did demonstrate the raw power of turbines in locomotives, the program ran into a dead end. The bunker fuel-burning GTELs stopped making sense once the cost of Bunker C rose alongside of continued maintenance costs. Further, diesel engines started getting more powerful and more efficient, further closing the gap.

Union Pacific began phasing the GTELs out in 1968, years after the coal turbine experiment failed, and the last GTEL hauled a train in 1970. A total of 55 GTELs were built, and Union Pacific made no effort to save any of them. Instead, they were sold, robbed of parts, and then scrapped. Only two units, UP 18 and UP 26, were rescued. The former lives at the Illinois Railway Museum, while the latter is at the Utah State Railroad Museum. Both are static displays and are unlikely to ever run again.

As for Union Pacific, it would go on to create the largest and most-powerful diesel-electric locomotive. But, eventually, the railroad ended its quest. Eventually, the Union Pacific just started doing what everyone else did and pulled heavy trains by linking diesel-electric locomotives together.

But it’s wild to think that for the vast majority of the 20th century, Union Pacific was so obsessed with power that it created all kinds of record-breaking locomotives. This was a railroad that created titans and experiments that seem absurd by modern standards. I wonder what might have happened had engineers figured out how to get turbines to live up to the promise.

Top graphic image: Union Pacific

Oh no don’t let some orange guy hear about this

After reading the first paragraph, I’ve got a question. Was it as long as a 747-200? If you say it a fourth time I might really believe it

Now I’m wondering if they ever tried to fit a coal gasification reactor into a consist.

This story of locomotive development reminds me a bit of supercomputing. Early supercomputers, like the Cray models when Seymour was still designing them, had all kinds of exotic tech. They were absolutely fascinating and wild machines with whimsy (like the functional giant red power button on the YMP-EL) and crazy tech.

And then consumer processors got too good, high speed interconnects got made, distributed code improved and now supercomputing is kind of a boring race of how many server processors can you afford to stitch together.

These moonshot type mega projects are a lot more fun, even if they aren’t as functional anymore.

Great article! Looking forward to you covering some of the Pennsy’s crazier experiments, like the S1.

OMG! What a massive train, and a massive story. Thank you SO MUCH for your efforts with train stories!

I thought they did end up with a working engine – the blue Oldsmobile that MotorWeek tested in the early ’80s. It was probably meant more as a threat to OPEC against another fuel shortage, but, it’s a neat footnote nonetheless. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0CAN5nO1ag0&t=2s

That is awesome – every time I see old faded cheeze-whiz colored UP rolling stock, it brings me back to my much younger days – rolling my HO-scaled versions around that small oval track every other train kid had.

That is so cool!

I know we state it often, but I need to state it again. We all really appreciate the work you put into the history of these long form articles on obscure machines. Yes, I’m speaking for everyone. Deal with it.

This is why we’re members, for the cool shit!

Mercedes has sent me down the “Bunker C fuel” rabbit hole. Never heard about it and never knew how ubiquitous it still is. As I read further, I’m sure I will find more easter eggs that will consume my day.

Kinda crazy how the global economy rides on the back of 2-stroke diesel engines running Bunker C.

Go ahead and speak for me. Mercedes research and writing is top-notch. Absolutely one of the reasons I’m a member.

I don’t know if you speak for the trees, but you definitely speak for me!